The influence of human growth hormone (HGH) on physiologic processes and exercise

Original Editor - Eugene DeLoachTop Contributors - Brandi Kindiger, Marilyn Kozlowski, Emily North, Lucinda hampton, Eugene DeLoach, Kylie Volk, Robert Long, Chelsea Miller, Samantha McGraw, 127.0.0.1, Kim Jackson, William Warmka, Jessica Hobbs, Kyle Covey, Ryan Lester, Taylor Ledford, Maddisen Coleman, Joel Frees, Vidya Acharya and Kayla Garrett

Introduction[edit | edit source]

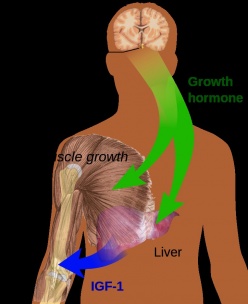

Human growth hormone (HGH), also known as somatotropin, is a peptide hormone secreted by the anterior pituitary gland.[1] HGH is an anabolic hormone that builds and repairs tissue such as collagen and muscle tissue throughout the body.[1] HGH release is stimulated from the release of growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH), which is released as a result of exercise.[2] HGH promotes the release of Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which promotes anabolic effects within the body.[2] It also helps facilitate the body's response to exercise. However, it's effects are not restricted to protein alone.[2] HGH is only released periodically, such as during certain stages of sleep, certain parts of the day, and with exercise.[2] Menstrual cycles and oral contraceptive use also have a significant impact on growth hormone levels.[3] The periodic release of HGH combined with its positive anabolic and metabolic effects on the body has led to supplementation of HGH to improve exercise performance.

Musculoskeletal Effects[edit | edit source]

HGH is an important component of metabolism because it increases lean body mass and promotes lipolysis.[1] This hormone, naturally produced by the body, is used in various forms for athletic improvement, hormone deficiencies, and other musculoskeletal conditions in diverse patient populations.

Athletes[edit | edit source]

HGH injections and supplements are widely abused by athletes to enhance performance. Nevertheless, there is not enough definitive evidence to show that HGH improves performance[4] Meinhardt et al. (2010) examines the effect of a 2mg dose of HGH on body composition, endurance, strength, power, and sprint capacity. The study uses recreationally active men and women in randomized control trials.[5] The results show increases in muscle mass and decreases in fat mass. Sprint capacity showed increases, but the results were small making it difficult to determine if HGH contributes to sprint performance. The increase in sprint capacity was not maintained after six weeks of discontinuation of HGH.[5] Endurance, strength, and power show no significant changes with HGH supplementation. Meinhardt et al. (2010) argues that growth hormone injections increase athletic exercise performance when given alone or with testosterone. In addition, participants that received growth hormones retained more body fluid and had more frequent joint pain than the control group.[5]

Liu et al. (2008) conducted a systematic review to explore the effects of growth hormone on athletic performance. The results include an increase in lean body mass and basal metabolic rate after HGH supplementation. The study shows why athletes use HGH as a means to improving body composition.[6] The increase in lean mass often leads to increases in metabolism, due to the increased need to build and repair the lean tissue. The study did not find any significant increases in muscular strength or improvement in aerobic exercise.[6]

HGH supplement usage among athletes is to improve body composition in both men and women. HGH increases lean body mass and decreases fat mass, but there is little research to support that HGH contributes to increases in strength, power, or endurance. HGH is currently banned by WADA due to its ability to increase muscle mass and potential to increase athletic performance.[7]

Older Adults[edit | edit source]

HGH injections are not only used for athletes but for the older population as well. One study analyzed the impact of recombinant human growth hormones and testosterone injections on aerobic and anaerobic fitness, body mass, and lipid profile in adult men.[8] The data demonstrates that recombinant human growth hormones and testosterone injections significantly increased aerobic and anaerobic capacity, led to changes in body compositions, and decreased total body fat and increased fat-free muscle. In another study, the authors analyzed whether treatment with testosterone and recombinant human growth hormones would increase muscle strength and mass in older adult patients.[9] The authors found that recombinant human growth hormones are connected with fluid preservation and improvements in muscle mass and strength that would translate into better aerobic exercise performance.

Adolescents[edit | edit source]

The effects of HGH supplementation have also been studied in adolescents, specifically in the treatment of young adults with cystic fibrosis. In one study, the authors stated that most of the time, diet alone may not give these patients the nutrients they need to grow and develop normally, so additional HGH may help this deficit. This study aimed to measure the effects of HGH on lung function and quality of life in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. They concluded that HGH had a positive effect on height, weight, and lean tissue mass, and some slight improvement on lung function.[10] No significant effects on quality of life were observed. HGH can be effective in therapy because if these children are able to build muscle and improve their lung function, they may be able to get better faster.

Cardiovascular Effects[edit | edit source]

For some individuals, the pituitary gland does not produce enough human growth hormone. These individuals experience a condition known as growth hormone deficiency (GHD). Variations in cardiac size and performance are common symptoms of GHD.[11] People with GHD have increased vascular profile risks, increased cholesterol levels, and increased carotid intima-medial thickness (IMT).[12] Elderly adults with hypopituitarism also face decreased left ventricular ejection fraction which leads to shorter bouts of exercise being possible.[13] In the same way that athletes and other individuals supplement HGH, it is important for those struggling with GHD to receive GH treatments to combat the symptoms above affecting the cardiovascular system. After six months of GH treatment, patients’ cardiac output at rest and cardiac response to exercise can improve to levels of those without any deficiency, showing that treatment can reverse serious cardiac issues associated with GHD.[14]

Body types that hold the majority of adipose tissue around the abdomen are more susceptible to reduced Growth Hormone (GH) secretion in both men and women. This is also directly associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) risk markers. Because GH plays an important role in the regulation of body composition, inflammation, and insulin resistance, this concept is important to grasp.[15] GH has been found to decrease abdominal adipose tissue leading to an improvement in overall body composition, as well as decrease liver fat and cardiovascular risk markers.[15]

Long term safety of HGH supplementation is still under investigation, but preliminary studies on mice show that there is not an increased risk to survival, longevity, or tumor development, but it is unknown if these findings will transfer to humans.[2] High doses of HGH supplementation can cause functionally weaker muscles despite increases in hypertrophy. Consistently high levels of GH may also result in hypertension, cardiac, and metabolic complications.[16] Abuse of Human Growth Hormone can cause significant health risks when taken with other drugs.[16] Despite these negative side effects, HGH is still one of the most commonly abused drugs, especially among athletes and athletic populations.

Exercise Prescription[edit | edit source]

Although HGH injections are one of the most common forms of HGH found in the body, the body can naturally produce HGH through certain exercise. Research shows that a heavy resistance exercise protocol (HREP) of high volume, 10RM load, and shorter rest periods produced a drastic stimulus of serum HGH levels within the body, while a lower volume and a longer rest period produced and clearer and more sustained elevation of HGH levels.[17]

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Hoffman JR, Kraemer WJ, Bhasin S, Storer T, Ratamess NA, Haff GG, Willoughby DS, Rogol AD. Position stand on androgen and human growth hormone use. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23(5), S1-S59. Doi: 10. 1519/JSC. 0b013e31819df2e6

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Kraemer WJ, Dunn-Lewis C, Comstock BA, Thomas GA, Clark JE, Nindl BC. Growth hormone, exercise, and athletic performance: A continued evolution of complexity. Current Sports Medicine Reports 2010;9(4):242. doi:10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181e976df

- ↑ Sunderland C, Tunaley V, Horner F, Harmer D, Stokes KA. Menstrual cycle and oral contraceptives’ effects on growth hormone response to sprinting. Journal of Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 2011;36(4):495-502.

- ↑ Saugy M, Robinson N, Saudan C, Baume N, Avois L, Mahgin P. Human growth hormone doping in sport. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:135-9.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Meinhardt U, Nelson AE, Hansen JL, Birzniece V, Clifford D, Leung K, . . . Ho KK. The effects of growth hormone on body composition and performance in recreational athletes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2010;152:568-77.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Liu H, Bravata DM, Olkin I, Friedlander A, Liu V, Roberts B, Hoffman AR. Systematic review: The effects of growth hormone on athletic performance. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2008;148(10):747-58. doi: 10. 7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00215

- ↑ Reardon CL, Creado S. Drug abuse in athletes. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 2014;5:95-105. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S53784

- ↑ Zajac A, Will M, Socha T, Maszczyk A, Chycki J. Effects of growth hormone and testosterone therapy on aerobic and anaerobic fitness, body composition and lipoprotein profile in middle-aged men. Annal of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 2014;21(1):156-60.

- ↑ Schroeder ET, He J, Yarasheski KE, Binder EF, Castaneda-Sceppa C, Bhasin S, . . . Sattler FR. Value of measuring muscle performance to assess changes in lean mass with testosterone and growth hormone supplementation. Europe Journal of Applied Physiology, 2011;112:1123-31.

- ↑ Thaker V, Haagensen AL, Carter B, Fedorowicz Z, Houston, BW. (2015). Recombinant growth hormone therapy for cystic fibrosis in children and young adults. The Cochrane Library, (5). 10.1002/14651858.CD008901.pub3.

- ↑ Moisey R, Orme S, Barker D, Lewis N, Sharp L, Clements RE, ... Tan LB. Cardiac functional reserve is diminished in growth hormone‐deficient adults. Cardiovasc Ther 2009:27(1):34-41.

- ↑ Murray RD, Wieringa G, Lawrance JA, Adams JE, Shalet SM. Partial growth hormone deficiency is associated with an adverse cardiovascular risk profile and increased carotid intima‐medial thickness. Clin Endocrinol 2010;73(4):508-15.

- ↑ Coloa A, Cuocolo A, Di Somma C. Impaired cardiac performance in elderly patients with growth hormone deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;(84)11. (accessed 2 Dec 2015)

- ↑ Cittadini A, Cuocolo A, Merola B, Fazio S, Sabatini D, Nicolai E., ... Sacca L. Impaired cardiac performance in GH-deficient adults and its improvement after GH replacement. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism, 1994;267(2):E219-E225.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Bredella M, Gerweck A, Lin E, Landa M, Torriani M, Schoenfeld D, . . . Miller K. Effects of GH on body composition and cardiovascular risk markers in young men with abdominal obesity. J Clinical Endocrinol Metab 2013;398(9):3864-72. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2063

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Birzniece V, Nelson AE, Ho KY. Growth hormone and physical performance. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2011;22(5):171-8. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2011.02.005

- ↑ Maresh C, Fry A. Endogenous anabolic hormonal and growth factor responses to heavy resistance exercise in males and females. Int J SportsMed. 1991;12:228-35. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Karl_Friedl2/publication/21294733_Endogenous_anabolic_hormonal_and_growth_factor_responses_to_heavy_resistance_exercise_in_males_and_females/links/54e7aee30cf27a6de10ac6ba.pdf