Neuroblastoma

Original Editors - Colleen Mathews from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Colleen Mathews, Lucinda hampton, Khloud Shreif, Elaine Lonnemann, Admin, Fasuba Ayobami, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, Tony Lowe, Evan Thomas and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Neuroblastoma is the most common solid tumour of childhood.

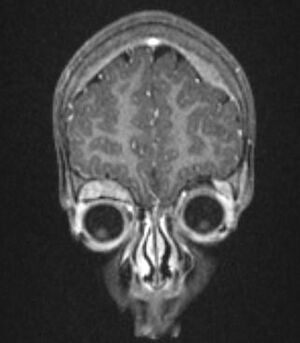

Image 1: Giant neuroblastoma in an Ethiopian shepherd child

It is almost exclusively a childhood cancer occurring most commonly between the ages of 0-5 years. Neuroblastomas are cancers that start in early nerve cells (called neuroblasts) of the sympathetic nervous system. This means that tumours can be found anywhere along this system; most commonly (about 50%) start in the adrenal glands (above the kidney), or near the spine, chest, neck or pelvis.

Rarely, a neuroblastoma has spread so widely by the time it is found, doctors can’t tell exactly where it started.[1]

Due to the high variability in its presentation, clinical signs and symptoms at presentation can range from benign palpable mass with distension to major illness from substantial tumor spread.[2]

Epidemiolgy[edit | edit source]

The tumours typically occur in infants and very young children (mean age of presentation being ~22 months) with 95% of cases diagnosed before the age of 10 years. Occasionally, they may be identified antenatally or immediately at birth.[3]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

There are no known reasons as to why this cancer occurs and there are no clear environmental links. Risk factors for the acquisition of mutations in key genes leading to neuroblastoma have yet to be identified, although exposures during conception and pregnancy are a topic of investigation. Neuroblastoma can develop either sporadically or be transmitted in the germline[2].

There are rare cases where neuroblastoma runs in families due to a genetic mutation, but in most cases there is no known genetic cause.[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Neuroblastoma presents in a variety of forms based upon the location of its manifestation and the size of the tumor.[4] Presentation is typically with pain or a palpable mass and abdominal distension. The neuroblastoma presentation changes if cancer has spread (metastasis), and if the tumor secretes hormones. At the time of the patient's diagnosis, neuroblastoma cells have already spread to other parts of the body 73% of the time due to local mass effect.

Other accompanying syndromes include:

- Hutchinson syndrome: skeletal metastases may present with skeletal pain or limping and irritability or proptosis with periorbital and cranial bumps.

- Pepper syndrome: hepatomegaly due to extensive liver metastasis

- Blueberry muffin syndrome: multiple cutaneous lesions

- Opsomyoclonus: rapid, involuntary conjugate fast eye movements

- Proptosis and periorbital ecchymoses ("raccoon eyes"): orbital metastases[3]

This video (3 minutes) is of the common symptoms of neuroblastoma

Location[edit | edit source]

Neuroblastomas arise from the sympathetic nervous system. Intra-abdominal disease (two-thirds of cases) is more prevalent than intrathoracic disease. Specific sites include:

- Adrenal glands: most common site of origin, 35%

- Retroperitoneum: 30-35%

- Coeliac axis

- Paravertebral sympathetic chain

- Posterior mediastinum: 20%

- Neck: 1-5%

- Pelvis: 2-3%

Treatment and Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Treatment depends on the patient's stage. Localised tumours considered to be 'low-risk' are surgically excised, and patients tend to do very well (see below). In 'high-risk' tumours, a combination of surgery, chemotherapy +/- bone marrow transplantation is employed, unfortunately with poor overall results. In some cases, where tumours are very large, pre-surgical chemotherapy to attempt to downstage the tumour may be administered.

Patients with stage 1, 2, or 4S have a better prognosis. Unfortunately 40-60% of patients present with stage 3 or 4 diseases 4. For advanced disease, the age of the child is most important.[3]

Stages of Neuroblastoma[edit | edit source]

Stage 1: The percentage of children diagnosed at this stage is 21%.

The primary tumor is located and isolated to one area of the body. The lymph nodes bilaterally are negative for cancer. The neuroblastoma cancer in this stage can be removed by surgery. Microscopic residual cancerous tissue may remain after the removal of the tumor.

Stage 2: The percentage of children diagnosed at this stage is 15%

- 2A: The primary tumor at this stage is confined to one area. However, it cannot be completely removed through surgery because of its larger size, proximity to other organs, or general location. The lymph nodes are negative bilaterally on both sides of the body for metastases.

- 2B: The primary tumor at this stage is confined to one area of the body. The tumor may or may not be completely surgically removed. The lymph nodes on the side of the body where the tumor is located are positive for metastasis of neuroblastoma. The lymph nodes on the opposite side of the body are negative for metastasis.

Stage 3: The percentage of children diagnosed at this stage is 17%.

Stage 4: The percentage of children diagnosed at this stage is 41%.

This stage of presentation occurs when neuroblastoma cells are found in the distal lymph nodes, liver, bone marrow, or additional organs.

Stage 4S: The percentage of children diagnosed at this stage is 6%. The presentation at this stage is typically found within infants. The primary tumor is isolated to one area of the body, but the tumor has metastasized to other regions of the body such as bone marrow, liver, or skin. Bone metastasis is rare in this category, with less than 10%.[6]

Poor prognostic factors: later age of onset: >18 months; higher stage: particularly in the presence of metastasis; N-Myc mutation; chromosome 1p deletion; unfavourable Shimada histology index

Better prognostic factors: TRK-A expression[3]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Associated co-morbidities of neuroblastoma include; Down syndrome, genetic abnormalities, AIDS, radiation exposure, chemo and radiation therapy. Research has found that focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver is demonstrated approximately ten years after diagnosis.[7] Organ failure is common after treatment for neuroblastoma including, Liver failure, Kidney failure, decreased immunological resistance, loss of blood cells produced by the bone marrow. A presentation of a genetic link has not been confirmed. Neuroblastoma can occasionally be associated with children with neurofibromatosis, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and nesidioblastosis, a pancreatic condition.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Rhabdomyosarcoma and Wilms Tumor.[8]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Neuroblastoma may be difficult to diagnose as symptoms often do not become apparent until the tumour has reached a certain size. Even then symptoms may be subtle and similar to other more common non-serious childhood diseases. As a result it often takes some time before the final diagnosis of neuroblastoma is made[1].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Is a non-selective drug that destroys fast-growing reproducing cells at particular stages in the growth cycle.[9] The most common chemotherapy drugs used to combat neuroblastoma are etoposide, daunorubicin, carboplatin, and cyclophosphamide.[4] Chemotherapy is most commonly administered by IV. The drug is utilized for neuroblastoma tumors that are located in the liver, lungs, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and a variety of other organs. Chemotherapy is most commonly used in tandem with surgery as a neoadjunctive or adjunctive therapy.

Has a variety of purposes including the following; destruction of lingering tumor cells following surgery of a tumor, reduction of tumor size prior to the surgery, treatment of large tumors that may not be affected by chemotherapy, in tandem with chemotherapy as part of high dose therapy including stem cell transplant (high risk neuroblastoma patients), and finally for pain relief.

Radiation destroys cancer cells by sending energy forming ions into the cancer cells which dislodges the electrons from the atoms. The result is radiation can destroy the cancer cells or change the genes. Similar to chemo, radiation cells destroy cells that are dividing.

Surgery can be performed in order to remove the entire tumor or portions of the tumor, followed by radiation or chemotherapy. Tumors that have metastasized or grown into areas of high risk may not be completely removed through resection. High-risk areas of tumor removal would include major blood vessels, organ involvement, and nerves.

Stem Cell Transplant Therapy

Is used for patients who are diagnosed with high-risk neuroblastoma. These patients are unlikely to improve with other treatments. Stem cell transplant involves collecting the child’s own blood to form new stem cells. The process is called apheresis, in which the blood that is collected is run through a machine that partitions the stem cells from the blood, and then returns the blood back to the child’s body. The stem cells are then stored for future usage. The patient is then treated with high-dose radiation and chemotherapy. Following the treatment, the patient’s stem cells are returned to the patient’s body similar to the process of a blood transfusion. Over the course of 3 to 4 weeks, the stem cells begin to form healthy blood cells in the bone marrow. There is a high risk of infection and bleeding during this treatment due to a decreased platelet count.

Immunotherapy

Includes therapy that is both passive and active. Active therapy utilizes the current immune system to fight against the pre-existing cancer cells. Cancer vaccines are also available to only destroy cancer cells. Passive immunotherapy uses man-made immune proteins such as monoclonal antibodies.[9]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Quality of life is an important theme when it comes to treating children with neuroblastoma and any form of childhood cancer. Side effects of the cancer treatment/medication (chemotherapy, radiation, etc.) and symptoms of cancer itself can lead to a risk of the following musculoskeletal and neurological issues.[9]

- Neurological changes including (peripheral neuropathy and radiculopathy)

- Musculoskeletal changes (disuse atrophy and joint contractures due to radiation fibrosis)

- Developmental Delay

- A generalized effect of a decrease in endurance, increase fatigue and decreased strength

The effects are not isolated to physical losses but also include psychosocial changes as well. The following are included in psychosocial considerations when treating a child with neuroblastoma and cancer.[9]

- Depression and anxiety

- Poor self-esteem

- Loss of purpose (due to the fact that most have changes in school life, social changes, and family life)

- Social Isolation

- Behavioral Issues

Research has also found late effects of childhood cancers including the following presentations.[9]

- Sensory changes (eyesight changes and hearing loss)

- Developmental Changes (learning disabilities and functional deficits)

- System Changes (reproductive issues, cardiopulmonary disease, osteoporosis, uneven growth of limbs, and decreased overall growth)

- Increased risk of secondary cancer

The above presentations are important in screening and for determining the physical therapy treatment of a child who presents with cancer or neuroblastoma. Physical therapy treatment should include a variety of considerations to address the limitations or deficits of the individual patient. When it is possible therapists can utilize group therapy to decrease social isolation and to develop psychosocial benefits. Wii rehabilitation treatment can address many deficits in the child with cancer such as balance, strength, and endurance.[9]

It is recommended by the ACSM (American College of Sports and Medicine) for cancer patients to perform 30-45 minutes of cardiovascular exercise, 3-5 days a week. The patient can walk, bike ride, etc. to develop cardiovascular benefits, strength, and maintain functional activities. Research has found that patients who exercise at this recommended level have increased endurance, decreased nausea, decreased overall fatigue, and an increase in their overall quality of life.[11]

Contraindications for Aerobic Exercise Laboratory Values:[12]

| Platelet Count | <50,000/mm3 |

| Hemoglobin | <10 g/dl |

| White Blood Cell Count | <3000/mm3 |

| Absolute Granulocytes | <2500/mm3 |

Overall, PT treatment has been proven through research to benefit the quality of life in a cancer patient of either a terminal or treatable diagnosis.[9]

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

- Retroperitoneal Mass with Intradural Extension: Value of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Neuroblastoma: diagnostic oncology case study.

- Case-control study of neuroblastoma in West-Germany after the Chernobyl accident: case-control study.

- Placental infiltration in congenital neuroblastoma: a case study with ultrastructure.

- Paternal occupation and neuroblastoma: a case-control study based on cancer registry data for Great Britain 1962–1999.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Mayo Clinic

- Medscape

- children's Neuroblastoma Cancer Foundation.

- American Cancer Society.

- National Cancer Institution

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Neuroblastoma Australia What is neuroblastoma? Available:https://www.neuroblastoma.org.au/pages/faqs/category/what-is-neuroblastoma (accessed 14.10.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mahapatra S, Challagundla KB. Cancer, neuroblastoma. Cancer. 1918 Apr 13;10:49. 2021 Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448111/ (accessed 14.10.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Radiopedia Neuroblastoma Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/neuroblastoma (accessed 14.10.2021)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Thiele CJ. Neuroblastoma. InHuman cell culture 2002 (pp. 21-53). Springer, Dordrecht.

- ↑ Health Apta. SYMPTOMS OF NEUROBLASTOMA. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L9r_y4BnIzw[last accessed on 29/ 6/2021]

- ↑ Children's Neuroblastoma Cancer Foundation: neuroblastoma staging. http://www.cncfhope.org/Staging_Neuroblastoma (accessed on 7 March 2011).

- ↑ Benz-Bohm G, Hero B, Gossmann A, Simon T, Körber F, Berthold F. Focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver in longterm survivors of neuroblastoma: how much diagnostic imaging is necessary?. European journal of radiology. 2010 Jun 1;74(3):e1-5.

- ↑ Medscape Reference: neuroblastoma. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/988284-clinical (accessed 9 March 2011).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Miale, S presenter. Improving the Quality of Life of Children with Cancer: The Role of Rehabilitation. Presented at Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association; 2011 February 9-12; New Orleans, Louisiana.

- ↑ Medscape. Neuroblastoma: Osmosis Study Video. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ej_2OOBmtPc[last accessed 29/6/2021]

- ↑ Cancer Supportive Care Programs: exercises for cancer supportive care. http://www.cancersupportivecare.com/exercise.html(accessed on 2 April 2011).

- ↑ Goodman, Snyder. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. St. Louis Missouri. 2007.