Multiligament Injured Knee Dislocation: Difference between revisions

Leana Louw (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Leana Louw (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

A multi-ligament-injured knee is commonly misnamed ''knee dislocation'' in medical literature. A dislocation causes a complete joint disruption, resulting in the loss of contact of the articular surfaces. Subluxation occurs when the articular surfaces stay in contact.<ref name=":1">Brautigan B, Johnson DL. The epidemiology of knee dislocations. Clinics in sports medicine 2000;19(3):387-97.</ref> Both of these fall under the term "multi-ligament-injured knee". A multi-ligament-injured knee is caused by injury of at least two out of the 4 major knee ligaments (namely [[Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstruction|ACL]], PCL, [[Lateral Collateral Ligament|LCL]] and [[Medial Collateral Ligament of the Knee|MCL]]).<ref name=":1" /><ref name="p1" /> It causes disruption of the active and passive stabilizers of the knee joint and is often linked with compromise to neurovascular structures and can potentially be limb theatening.<ref name=":2">Fanelli GC, editor. The multiple ligament injured knee: A practical guide to management. New York: Springer Science, 2004 | A multi-ligament-injured knee is commonly misnamed ''knee dislocation'' in medical literature. A dislocation causes a complete joint disruption, resulting in the loss of contact of the articular surfaces. Subluxation occurs when the articular surfaces stay in contact.<ref name=":1">Brautigan B, Johnson DL. The epidemiology of knee dislocations. Clinics in sports medicine 2000;19(3):387-97.</ref> Both of these fall under the term "multi-ligament-injured knee". A multi-ligament-injured knee is caused by injury of at least two out of the 4 major knee ligaments (namely [[Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstruction|ACL]], PCL, [[Lateral Collateral Ligament|LCL]] and [[Medial Collateral Ligament of the Knee|MCL]]), normally associated with considerable ligamentous disruption.<ref name=":1" /><ref name="p1" /><ref name=":3">Robertson A, Nutton RW, Keating JF. Dislocation of the knee. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume 2006;88(6):706-11.</ref> It causes disruption of the active and passive stabilizers of the knee joint and is often linked with compromise to neurovascular structures and can potentially be limb theatening.<ref name=":2">Fanelli GC, editor. The multiple ligament injured knee: A practical guide to management. New York: Springer Science, 2004.</ref> | ||

== Clinically relevant anatomy == | == Clinically relevant anatomy == | ||

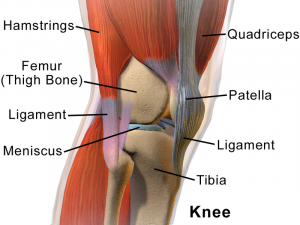

The [[Knee|knee joint]] is made up of articulations of the distal femur, proximal tibia and patella.<ref name=":2" /> | The [[Knee|knee joint]] is made up of articulations of the distal femur, proximal tibia and patella.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

[[File:Knee Anatomy Side View.png|left|thumb]] | |||

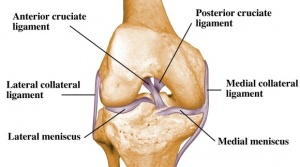

'''Ligaments:'''<ref name=":2" /> | '''Ligaments:'''<ref name=":2" /> | ||

| Line 18: | Line 17: | ||

* [[Lateral Collateral Ligament|LCL]] | * [[Lateral Collateral Ligament|LCL]] | ||

* [[Medial Collateral Ligament of the Knee|MCL]] | * [[Medial Collateral Ligament of the Knee|MCL]] | ||

[[File:Ligaments-of-the-knee.jpg|left|thumb|300x300px]] | |||

'''\''' | |||

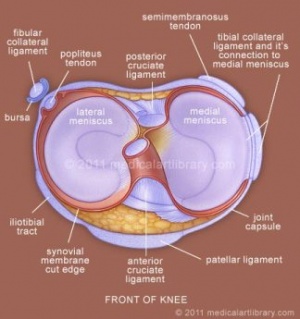

'''Menisci:'''<ref name=":2" /> | '''Menisci:'''<ref name=":2" /> | ||

* [[Medial meniscus]] | * [[Medial meniscus]] | ||

* [[Lateral meniscus]] | * [[Lateral meniscus]] | ||

[[File:Knee-joint-meniscus.jpg|left|thumb]] | |||

'''Muscles:'''<ref name=":2" /> | '''Muscles:'''<ref name=":2" /> | ||

| Line 67: | Line 70: | ||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | == Epidemiology /Etiology == | ||

Knee dislocation is estimated to be less than 0, | Knee dislocation is estimated to be less than 0,2% of all orthopedic injuries. Total knee dislocations are rare and usually happen after major trauma, including falls, car crashes, and other high-speed injuries.<ref name=":3" /> Spontaneous dislocation is often seen in cases associated with obesity.<ref name="p1"/> Knee dislocations can also present in congenitally and has an incidence of approximately 1 per 100,000 live births. 40-100% of these cases have additional musculoskeletal anomalies.<ref name="p3">Flint L, Meredith JW, Schwab CW. Trauma: contemporary principles and therapy. Philadelphia; 2008.</ref> | ||

* Anterior dislocation = 40% | |||

* Posterior dislocation = 33% | |||

* Medial dislocation = 4% | |||

* Lateral dislocation = 18% | |||

* Rotary dislocation = 5% | |||

* Complete disruption of all 4 major knee stabilizing ligaments: 11% | |||

<ref name=":3" /> | |||

Low-velocity injuries - morbid obese (trivial trauma), lax ligaments | Low-velocity injuries - morbid obese (trivial trauma), lax ligaments | ||

| Line 78: | Line 89: | ||

== Complications == | == Complications == | ||

* Vascular disruption | |||

* Common peroneal nerve injuries | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* Iatrogenic vascular injury | * Iatrogenic vascular injury | ||

* Arthrofibrosis | * Arthrofibrosis | ||

| Line 84: | Line 99: | ||

Most multi-ligament knee injuries are easily reducible with minimal assistance or even spontaneous.<ref name=":1" /> Dislocation can be suspected based on physical exam findings of joint instability/ligamentous injuries, but also based on hemarthosis and tenderness to palpation.<ref name="p4">LCDR Damon Shearer, DO; Laurie Lomasney, MD; Kenneth Pierce, MD. Dislocation of the knee: imaging findings, J Spec Oper Med. 2010 Winter;10(1):43-7. Level of evidence: A1</ref> It is often difficult to diagnose if a reduced knee was dislocated or subluxed without clinical witness or radiological evidence.<ref name=":1" /> Associated meniscal, osteochondral, and neurovascular injuries are often present and can complicate management.<ref name="Rihn et al.">Rihn J, Groff Y, Harner C & Cha P. The acutely dislocated knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;12(5): 334-46. A1</ref> | Most multi-ligament knee injuries are easily reducible with minimal assistance or even spontaneous.<ref name=":1" /> Dislocation can be suspected based on physical exam findings of joint instability/ligamentous injuries, but also based on hemarthosis and tenderness to palpation.<ref name="p4">LCDR Damon Shearer, DO; Laurie Lomasney, MD; Kenneth Pierce, MD. Dislocation of the knee: imaging findings, J Spec Oper Med. 2010 Winter;10(1):43-7. Level of evidence: A1</ref> It is often difficult to diagnose if a reduced knee was dislocated or subluxed without clinical witness or radiological evidence.<ref name=":1" /> Associated meniscal, osteochondral, and neurovascular injuries are often present and can complicate management.<ref name="Rihn et al.">Rihn J, Groff Y, Harner C & Cha P. The acutely dislocated knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;12(5): 334-46. A1</ref> | ||

'''Mechanism of injury:'''<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* Anterior dislocation: Hyperextention force | |||

* Posterior dislocation: Anterioposterior force (e.g. dashboard injury) | |||

* Medial dislocation: Varus force (often associated with tibial plateau fractures) | |||

* Lateral dislocation: Valgus force (often associated with tibial plateau fractures) | |||

* Rotary dislocation: Combination of forces | |||

'''Classification:'''<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* Acute: < 3 weeks post injury | |||

* Chronic: > 3 weeks post injury | |||

'''Associated injuries:'''<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* Popliteal artery (19%) | |||

* Common peroneal nerve (20%) | |||

* Vascular injuries (19%): | |||

** High-velocity injury (65%) | |||

** Low-velocity injury (4.8%) | |||

* Fractures (including avulsion) - distal femur, proximal tibia (16%) | |||

* Compartment syndrome | |||

Ligamentous injuries have characteristics such as: | Ligamentous injuries have characteristics such as: | ||

| Line 168: | Line 203: | ||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Knee dislocations occur in 5 main types: Anterior, posterior, medial, lateral and rotary. Anterior dislocations represent more than 70% of knee dislocations. Rotary dislocations can further be divided into anteromedial, anterolateral, posteromedial and posterolateral injuries.</span><ref name="p2">Henrichs A. A review of knee dislocations. Journal of Athletic Training 2004;39(4):365–369.</ref> | |||

Knee dislocation often goes hand-in-hand with concomitant injuries to other structures such as nerves and blood vessels. It is very important to exclude injuries to perineal nerve and popliteal artery.<ref name=":0">Walters J, editor. Orthopaedics - A guide for practitioners. 4th Edition. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2010.</ref> | Knee dislocation often goes hand-in-hand with concomitant injuries to other structures such as nerves and blood vessels. It is very important to exclude injuries to perineal nerve and popliteal artery.<ref name=":0">Walters J, editor. Orthopaedics - A guide for practitioners. 4th Edition. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2010.</ref> | ||

| Line 180: | Line 217: | ||

== Examination == | == Examination == | ||

It is very important to do thorough and repeated evaluation of the neurological and vascular status for signs of injury to the common peroneal nerve, popliteal artery and to assess for compartment syndrome. | |||

Ankle-brachial index: Can be used to determine if angiography is needed (threshold of <0.9 can positively predict a vascular injury in need of surgery) | |||

''The unreduced dislocation of the knee offers an obvious diagnosis, but if the dislocation has reduced spontaneously the extent of the soft-tissue injury to the knee may not be apparent. An uncontained haemarthrosis causing extensive bruising and swelling on either the medial or lateral side of the knee suggests a major disruption of the joint capsule. This should alert the examiner to the possibility that a dislocation has occurred. Clinical assessment of specific knee ligaments may be difficult because of pain. Recurvatum on passive elevation of the limb is a characteristic finding with disruption of the PCL and posterior capsule. Gross laxity on varus or valgus testing with the knee in full extension also indicates a major capsular disruption. In the presence of bicruciate injury, testing of anteroposterior stability using the Lachman test will be grossly abnormal in both directions. The anterior drawer test is often difficult to perform reliably in the acute situation because of pain, limited knee flexion and muscle spasm. Similarly, the pivot-shift or reverse pivot-shift tests are impossible to undertake in the acutely swollen knee if the MCL is disrupted. In addition, in most other cases there is usually too much discomfort to allow these tests to be performed easily.'' | |||

''In the chronic situation the pivot- and reverse pivot-shift tests can be carried out without difficulty and are much more helpful. The dial test, performed at 30° and 90° of knee flexion, may help in clarifying involvement of the PCL and the posterolateral corner. An increased degree of external rotation of the tibia in comparison with the normal knee is considered to indicate insufficiency of the posterolateral corner at 30° and laxity of the posterolateral corner at 90°. '''UNEDITED - DO NOT USE AS IS''''' | |||

#X-rays: to make sure there are no fractures in the bone. | #X-rays: to make sure there are no fractures in the bone. | ||

#Examination of pulses: This is necessary to make sure there are no any<br>injuries to the arteries. The physician will search for a pulse in the foot. | #Examination of pulses: This is necessary to make sure there are no any<br>injuries to the arteries. The physician will search for a pulse in the foot. | ||

Revision as of 21:17, 20 July 2018

***Editing in process***

Original Editors - Caro De Koninck

Top Contributors - Estelle Hovaere, Leana Louw, Caro De Koninck, Admin, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Daphne Jackson, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk and Naomi O'Reilly

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

A multi-ligament-injured knee is commonly misnamed knee dislocation in medical literature. A dislocation causes a complete joint disruption, resulting in the loss of contact of the articular surfaces. Subluxation occurs when the articular surfaces stay in contact.[1] Both of these fall under the term "multi-ligament-injured knee". A multi-ligament-injured knee is caused by injury of at least two out of the 4 major knee ligaments (namely ACL, PCL, LCL and MCL), normally associated with considerable ligamentous disruption.[1][2][3] It causes disruption of the active and passive stabilizers of the knee joint and is often linked with compromise to neurovascular structures and can potentially be limb theatening.[4]

Clinically relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

The knee joint is made up of articulations of the distal femur, proximal tibia and patella.[4]

Ligaments:[4]

\

Menisci:[4]

Muscles:[4]

- Anterior:

- Quadriceps

- Lateral:

- Iliotibial band

- Biceps femoris

- Popliteus

- Medial:

- Pes anserinus (sartorius, gracilis, semitendinosus)

- Semimembranosus

- Posterior:

Vasculature:[4]

- Femoral artery

- Popliteal artery

Innervation:[4]

- Terminal branches of the following nerves:

- Cutaneous nerves:

- Posterior & lateral femoral cutaneous

- Lateral sural cutaneous

- Saphenous

- Obturator

Medial stabilizers of the knee (against valgus stress):[4]

- Superficial: Sartorius, fascia

- Middle: Posterior oblique ligament, semimembranosus, MCL

- Deep: Joint capsule, medial capsular ligament

Posteriolateral stabilizers of the knee:[4]

- Superficial: Iliotibial band, biceps femoris, fascia

- Middle: Patellar retinaculum, patellofemoral ligaments

- Deep: LCL, popliteus tendon, popliteofibular ligament, fabellofibular ligament, arcuate ligament, joint capsule

See the page on the knee joint for in-depth information the anatomy and kinematics of the knee. This background is needed to understand knee dislocations better.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Knee dislocation is estimated to be less than 0,2% of all orthopedic injuries. Total knee dislocations are rare and usually happen after major trauma, including falls, car crashes, and other high-speed injuries.[3] Spontaneous dislocation is often seen in cases associated with obesity.[2] Knee dislocations can also present in congenitally and has an incidence of approximately 1 per 100,000 live births. 40-100% of these cases have additional musculoskeletal anomalies.[5]

- Anterior dislocation = 40%

- Posterior dislocation = 33%

- Medial dislocation = 4%

- Lateral dislocation = 18%

- Rotary dislocation = 5%

- Complete disruption of all 4 major knee stabilizing ligaments: 11%

Low-velocity injuries - morbid obese (trivial trauma), lax ligaments

High velocity knee injuries 30% vascular injury - high

41% popliteal artery injury

41% neurologic injury with 50% chance of neurologic recovery at follow-up; 71% peroneal, 29% peroneal and tibial; 29%AKA

Complications[edit | edit source]

- Vascular disruption

- Common peroneal nerve injuries

- Iatrogenic vascular injury

- Arthrofibrosis

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Most multi-ligament knee injuries are easily reducible with minimal assistance or even spontaneous.[1] Dislocation can be suspected based on physical exam findings of joint instability/ligamentous injuries, but also based on hemarthosis and tenderness to palpation.[6] It is often difficult to diagnose if a reduced knee was dislocated or subluxed without clinical witness or radiological evidence.[1] Associated meniscal, osteochondral, and neurovascular injuries are often present and can complicate management.[7]

Mechanism of injury:[3]

- Anterior dislocation: Hyperextention force

- Posterior dislocation: Anterioposterior force (e.g. dashboard injury)

- Medial dislocation: Varus force (often associated with tibial plateau fractures)

- Lateral dislocation: Valgus force (often associated with tibial plateau fractures)

- Rotary dislocation: Combination of forces

Classification:[3]

- Acute: < 3 weeks post injury

- Chronic: > 3 weeks post injury

Associated injuries:[3]

- Popliteal artery (19%)

- Common peroneal nerve (20%)

- Vascular injuries (19%):

- High-velocity injury (65%)

- Low-velocity injury (4.8%)

- Fractures (including avulsion) - distal femur, proximal tibia (16%)

- Compartment syndrome

Ligamentous injuries have characteristics such as:

- Long-term joint instability

- Patient’s mobility

- Quality of life

The most common problems of knee dislocation are stiffness, secondary to arthrofibrosis or failure of a ligament repair or reconstruction. In the long term, it is reported that up to 50% of patients may develop post-traumatic Osteoarthritis

Compartment syndome - ischaemic & compression nerve injury

It has been observed that many multiple-ligament–injured knees present in a reduced position.3, 12, 16, 32 In many cases, knee dislocations reduce easily and spontaneously or with minimal assistance. Without a clinical witness or radiographicevidence of a true dislocation, the clinician is unable to determine whether the knee subluxed or dislocated based solely on a physical examination. Some investigators have advocated that all bicruciate ligament tears be labeled knee dislocations, regardless of presentation32; however, knee dislocation is possible without bicruciate ligament tear.1, 4, 25 Nonetheless, the multiple-ligament–injured knee commonly remains referred to as a knee dislocation.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Classifications of knee dislocations have been based on either an anatomical and/or a positional scheme. The positional classification categorizes knee dislocations according to the tibial position in relation to the femur also known as the Kennedy Classification, named after the author in 1963. Five types were initially defined [2] :

- anterior (Fig. 1)

- posterior (Fig. 2)

- lateral

- medial

- rotatory

Rotatory knee dislocations were subdivided into four groups: anteromedial, anterolateral, posteromedial and posterolateral.

Although well established and useful, the positional classification system has limitations. Up to 50% of knee dislocations are spontaneously reduced before evaluation and cannot be classified with the positional classification. Therefore an anatomical system was developed, based on ligament injury with additional designations of C (arterial injury) and N (neural injury)[8].

KDI is described as —> a single cruciate tear

KDII —> bicruciate tears without collateral tears

KDIIIM —> bicruciate tears with involvement of a medial collateral ligament

(MCL) KDIIIL —> involvement of a lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and

posterolateral corner (PLC) tear

KDIV —> involves all four ligaments and KDV involves a fracture-dislocation.

In general, the higher the number, the greater the injury to the knee.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Knee dislocations occur in 5 main types: Anterior, posterior, medial, lateral and rotary. Anterior dislocations represent more than 70% of knee dislocations. Rotary dislocations can further be divided into anteromedial, anterolateral, posteromedial and posterolateral injuries.[9]

Knee dislocation often goes hand-in-hand with concomitant injuries to other structures such as nerves and blood vessels. It is very important to exclude injuries to perineal nerve and popliteal artery.[10]

Physical examination of a patient with a suspected knee dislocation should take place shortly after the injury is sustained. (Levy et al., 2010) Recognition is the most important aspect of the diagnosis. When a knee dislocation is suspected, neurovascular assessment is needed. Patients with a knee dislocation complain of severe pain and instability. Also they are unable to continue sports or activities of daily living. Pain tends to be diffuse with palpation and knee ROM's are limited. The Lachman and pivot-shift tests should be performed to test ACL integrity and the posterior drawer and posterior sag tests should be performed to test PCL integrity. Varus and Valgus stress tests should be carried out to test for MCL and LCL injury. (Henrichs, 2004, A1)[11]

All cases of suspected knee dislocation should have an ankle-brachial index performed, reserving arteriography for those with an abnormal finding. (Levy et al., 2010, A1)[12]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Recent prospective studies declare that patients who achieve a good Lysholm score, could perform activities on a regular basis and could perform hop tests comparable to the other knee.[2]

Examination[edit | edit source]

It is very important to do thorough and repeated evaluation of the neurological and vascular status for signs of injury to the common peroneal nerve, popliteal artery and to assess for compartment syndrome.

Ankle-brachial index: Can be used to determine if angiography is needed (threshold of <0.9 can positively predict a vascular injury in need of surgery)

The unreduced dislocation of the knee offers an obvious diagnosis, but if the dislocation has reduced spontaneously the extent of the soft-tissue injury to the knee may not be apparent. An uncontained haemarthrosis causing extensive bruising and swelling on either the medial or lateral side of the knee suggests a major disruption of the joint capsule. This should alert the examiner to the possibility that a dislocation has occurred. Clinical assessment of specific knee ligaments may be difficult because of pain. Recurvatum on passive elevation of the limb is a characteristic finding with disruption of the PCL and posterior capsule. Gross laxity on varus or valgus testing with the knee in full extension also indicates a major capsular disruption. In the presence of bicruciate injury, testing of anteroposterior stability using the Lachman test will be grossly abnormal in both directions. The anterior drawer test is often difficult to perform reliably in the acute situation because of pain, limited knee flexion and muscle spasm. Similarly, the pivot-shift or reverse pivot-shift tests are impossible to undertake in the acutely swollen knee if the MCL is disrupted. In addition, in most other cases there is usually too much discomfort to allow these tests to be performed easily.

In the chronic situation the pivot- and reverse pivot-shift tests can be carried out without difficulty and are much more helpful. The dial test, performed at 30° and 90° of knee flexion, may help in clarifying involvement of the PCL and the posterolateral corner. An increased degree of external rotation of the tibia in comparison with the normal knee is considered to indicate insufficiency of the posterolateral corner at 30° and laxity of the posterolateral corner at 90°. UNEDITED - DO NOT USE AS IS

- X-rays: to make sure there are no fractures in the bone.

- Examination of pulses: This is necessary to make sure there are no any

injuries to the arteries. The physician will search for a pulse in the foot. - An arteriogram (X-ray of the artery): This X-ray is necessary to detect

injuries to the artery. Some medical centers may also use special

ultrasound or Doppler machines to assess the blood flow in the arteries.

Although there is proof that physical examination of the popliteal artery is

accurate enough to rely on. The presence or absence of an injury of the

popliteal artery after knee dislocation can be safely and reliably predicted,

with a 94.3% positive predictive value and 100% negative predictive

value.[2] - Examination of nerves: It is possible that the nerves may have been

damaged. Moving the foot up and down and turning the foot inside

(inversion) and outside (eversion) are important muscle movements to

examine. Any feeling of numbness is an indicating sign for nerve damage.[6]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Knee dislocations should be reduced as soon as possible. An angiogram should be done to investigate if any vascular injuries are present.[10]

Knee dislocation with vascular injury:[10]

- Vascular repair

- Repair posterior capsule tear

- Knee stabilization with a range of motion brace (e.g. Donjoy/Exoskeleton)

- Remaining instability should be addressed at a later stage

Knee dislocation without a vascular injury:[10]

- Primary repair (when swelling permits)

- Stabilize in a plaster of paris cast or range of motion brace (e.g. Donjoy/Exoskeleton)

Definitive management of acute knee dislocation remains a matter of debate. Surgical reconstruction of the collateral ligaments, the cruciate ligaments, and the PCL on the contrary seems way better.Also Henrichs (2004, A1)[2] says that surgical treatment had proven to be much more beneficial for active patients. Conservative treatment on the other hand is often chosen if the joint feels relatively stable postreduction or if the patient is older or sedentary with intact colletarel ligaments.Conservative treatment means applying a brace that limits the range of motion of the knee.[13]

Patients who are diagnosed with knee dislocation at birth are examined within 24 hours after birth. Treatment with conservative methods at an early stage is most likely to yield successful results. These conservative methods include direct reduction under gentle, persistent manual traction.[14]

There are also non-conservative methods that can be used later on such as Percutaneous quadriceps recession (PQR) and V–Y quadricepsplasty. [2]After both procedures an above knee cast is applied to ensure knee flexion. Important is that the cast does not push the tibial plateau to anterior and therefore re-dislocate the knee. After six weeks the cast is removed. No splints or physiotherapy are advised.[2]

Percutaneous quadriceps recession (PQR) as described by Roy & Crawford (1989): Medial and lateral stab incisions are made at the superior border of the patella to divide the medial and lateral quadriceps and retinaculum. The knee is then forced into flexion, while applying direct forward pressure on the femoral condyles with the fingers.[9]

V–Y quadricepsplasty as described by Curtis and Fisher (1969): There is made an incision in the central part of the quadriceps tendon in a fashion that allows V–Y advancement. The iliotibial band is released. The anterior capsule of the knee is divided transversely as far as the collateral ligaments, and the quadriceps muscle is mobilized. The knee is then reduced and flexed to 90°. The lengthened quadriceps is resutured with the knee held at 30°. This treatment has a higher morbidity compared with the PQR due to a long incision with scarring, adhesions,and wound breakdown, as well as blood loss. However, V-Y quadricepsplasty is more successful in attaining and prolonging reduction in severe and resistant cases.[9]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Treatment is dependent of the damaged structures. Each patient will have a different treatment which depends on the current stability of the patient, and eventually the other injuries that occurred in the injured limb. The ultimate goal of the therapy is to restore stability and regain a pain free functional mobility.[5]

Depending on the medical treatment given, there are 2 rehabilitation programs:

- Nonoperative treatment:

Allows the healing of the capsular and collateral ligaments so that varus and valgus stability can be restored

- 6 to 8 weeks initial mobilization

- Weight bearing exercises

- Passive and active training of the range of motion

- Muscle strengthening

After conservative treatment, rehabilitation may begin immediately. The first exercises are upper and midbody exercises, along with single-leg stationary bicycling in order to maintain

cardiovascular conditioning. Quadriceps strengthening is important to prevent patellofemoral problems during rehabilitation. During early exercises, wearing a brace is important to limit ROM from 90°of flexion to 45°of extension. Light manual-resistance exercises may be performed in this range as tolerated. As the patient progresses, other resistance machines such as Biodex may be used in place of manual therapy. After 8 weeks of rehabilitation, the patient may begin doing exercises with a leg-press machine. During this face, the knee needs only minimal protection. These exercises should be followed by high-speed exercises with light resistance. Once sufficient ROM and strength have been regained, proprioceptive exercises may be integrated.[15]

- Operative treatment

To restore the anatomical structures with sufficient strength, passive and active training of the assisted ROM are needed. Most patients lose some motion and do not recover entirely.

Postsurgical rehabilitation for this injury varies according to which ligaments were injured and repaired. Initially, a brace with limits of 40° of extension and 70° of flexion should be worn if a continuous passive-motion machine is used. From the start, quadriceps settings are performed in order to increase quadriceps control. In the first postoperative week it's also very important to work on full extension. This can be achieved by doing therapeutic exercises. From weeks 7 to 10, ROM therapy can begin, stressing full extension and flexion. After weeks 11 to 24, the patient should have regained full flexion and extension and strength training can begin using closed kinetic chain exercises (squats, light leg presses,..). Strength training continues through weeks 25 to 36 but becomes more advanced. After the patient has reestablished bulk and strength around the knee, proprioceptive exercises are integrated. After week 37 the patient can return to sports and heavy work, provided that he or she has passed functional tests.[9]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

A patient with a knee dislocation is faced with a long rehabilitation program, with return to full activity taking at least 9 to 12 months. Most of the knee dislocations require reconstruction surgery. That is because major injury to the artery occurs in 21%-32% of all knee dislocations and because of the severe ligament injury. After the treatment and surgery the results are good. In most cases the damaged knees return to an almost normal state. Chronic pain is a common problem, occurring in 46% of cases. The prognosis is best with an optimal rehabilitation exercise program.[16]

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Web MD, Knee pain health center. http://www.webmd.com/pain-management/knee-pain/knee-dislocation (assessed 14 april 2011)

Henrichs A. A review of knee dislocations. Journal of Athletic Training 2004;39(4): 365–369

Rihn J, Groff Y, Harner C & Cha P. The acutely dislocated knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;12(5): 334-46.

Levy B, Peskun C, Fanelli G, Stannard J, Stuart M, MacDonald P, Marx R, Boyd J & Whelan D. Diagnosis and management of knee dislocations. Phys Sportsmed. 2010 Dec;38(4): 101-11.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

add text here

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Brautigan B, Johnson DL. The epidemiology of knee dislocations. Clinics in sports medicine 2000;19(3):387-97.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Howells NR, Brunton LR, Robinson J, Porteus AJ, Eldridge JD, Murray JR. Acute knee dislocation: An evidence based approach to the management of the multiligament injured knee. Injury 2011;42(11):1198-204.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Robertson A, Nutton RW, Keating JF. Dislocation of the knee. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume 2006;88(6):706-11.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Fanelli GC, editor. The multiple ligament injured knee: A practical guide to management. New York: Springer Science, 2004.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Flint L, Meredith JW, Schwab CW. Trauma: contemporary principles and therapy. Philadelphia; 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 LCDR Damon Shearer, DO; Laurie Lomasney, MD; Kenneth Pierce, MD. Dislocation of the knee: imaging findings, J Spec Oper Med. 2010 Winter;10(1):43-7. Level of evidence: A1

- ↑ Rihn J, Groff Y, Harner C & Cha P. The acutely dislocated knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;12(5): 334-46. A1

- ↑ R. Schenck Jr. MD „Classification of knee dislocations” Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, Vol 11, No 3 (July), 2003) Level of evidence 2A

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Henrichs A. A review of knee dislocations. Journal of Athletic Training 2004;39(4):365–369.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Walters J, editor. Orthopaedics - A guide for practitioners. 4th Edition. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2010.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHenrichs et al. - ↑ Levy B, Peskun C, Fanelli G, Stannard J, Stuart M, MacDonald P, Marx R, Boyd J & Whelan D. Diagnosis and management of knee dislocations. Phys Sportsmed. 2010 Dec;38(4): 101-11. A1

- ↑ Demirag, B. et al, Knee dislocations: an evaluation of surgical and conservative treatment, Turkish Journal of Trauma & Emergency Surgery Ulus Travma Derg 2004;10(4):239-244:Grade of recommendation: B

- ↑ Chun-Chien Cheng; Jih-Yang Ko. Early Reduction for Congenital Dislocation of the Knee within Twenty-four Hours of Birth. Chang Gung Med J 2010;33:266-73. Grade of recommendation: C

- ↑ John M. Siliski et co, traumatic disorders of the knee. Grade of recommendation: B.

- ↑ William C. Shiel Jr., MD, FACP, FACR ; “Knee Dislocation”, http://www.emedicinehealth.com/knee_dislocation/fckLRpage10_em.htm#prognosis_of_knee_dislocation, bezocht op 6/11/13. Grade of recommandation: C.