Lateral meniscus

Original Editor - Aarti Sareen

Top Contributors - Aarti Sareen, Kim Jackson, Admin, Evan Thomas, Wendy Snyders, Rachael Lowe, Oyemi Sillo, WikiSysop and Fasuba Ayobami

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The word meniscus is derived from the Greek work meniskos, which means "crescent". At knee joint, the meniscus plays a major role in congruency of the joint and forms the concavity in which the femoral condyles sits. The meniscii rest between the femur and the tibia. The rubbery texture of the meniscii is due to their fibrocartilagenous structure and they consist of about 75% Type 1 collagen[1]. One meniscus is on the inner side of the knee (medial meniscus), while the other meniscus is on the outer side of the knee (lateral meniscus)[1].

Anatomy and attachment[edit | edit source]

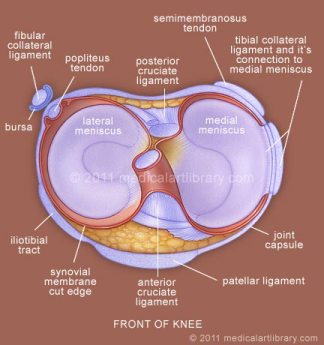

The lateral meniscus is almost circular and covers a larger portion of the tibial articular surface than the medial meniscus. The lateral meniscus is consistent in width throughout its course. The anterior horn of the lateral meniscus blends into the attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), whereas the posterior horn attaches just behind the intercondylar eminence, often blending into the posterior aspect of the ACL. There is no attachment of the lateral meniscus to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). Its peripheral attachment is interrupted posteriorly to where the popliteal tendon passes.

The capsular components attach the lateral meniscus to the tibia less firmly than the medial meniscus. The lateral meniscus is more mobile than the medial meniscus and can translate 9 to 11 mm in an anteroposterior direction[1]. This mobility is explained by the close proximity of the attachments of the anterior and posterior horns and the lack of attachment to the capsular ligament posterolaterally. The firm attachment of the arcuate ligament to the lateral meniscus and the attachment of the popliteus muscle to both the arcuate ligament and meniscus ensure the dynamic retraction of the posterior segment of the meniscus during internal rotation of the tibia on the femur, as the knee begins to flex from its fully extended position.

VASCULAR SUPPLY:

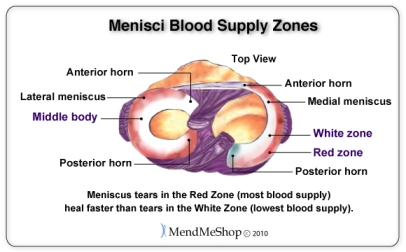

The vascular supply of the menisci originates predominately from the inferior and superior lateral and medial genicular arteries. During the first year of life, the meniscii contain blood vessels throughout them and shortly after the child starts weight-bearing (18 months), the vascular and lymph supply diminishes to only 25-33% of the outer body of the menisci[2]. The vascularity diminishes so much, that in fourth decade of life, only the periphery is vascular whereas the centre of the menisci is avascular. The centre portion is completely dependent upon the synovial fluid diffusion for nutrition [1]. The central avascular portion of menisci either does not heal completely or heal at all after injury[2].

NERVE SUPPLY:

The horns of the meniscii and the peripheral vascularized portion of the meniscal bodies are well innervated with free nerve endings (nociceptors) and three different mechanoreceptors (Ruffini corpuscles, pacinian corpuscles, and Golgi tendon organs)[2][3][4].

Injury/Tear[edit | edit source]

The most common mechanism of menisci injury is when the limb is twisted with the foot anchored on the ground. The person's foot is often by another player's body. A slow twisting force may also cause the tear. [5][6]. A valgus force of the knee and also internal rotation of the foot and the lower leg in relation to the femur when the knee joint is flexed to 70–90°, can cause the lateral meniscal tear.[6]

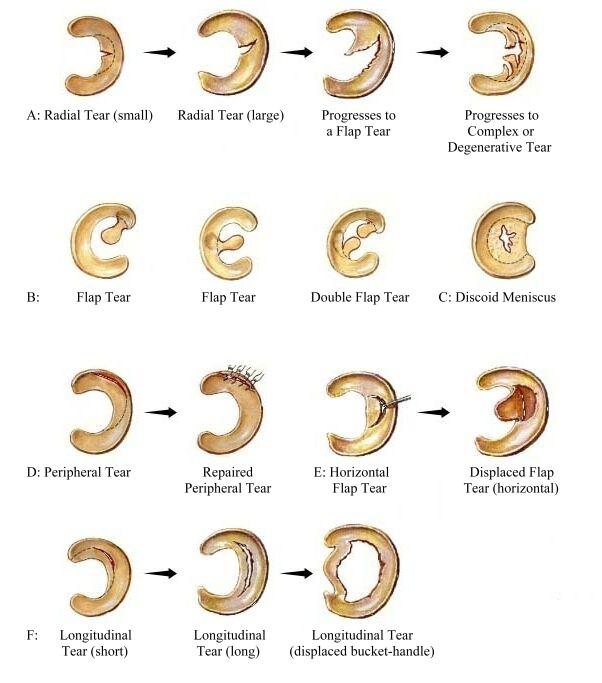

The different types of meniscal tears include:

- Longitudinal

- Radial

- Bucket handle

- Flap

- Horizontal cleavage

- Degenerative

The patient with a meniscal injury complain of knee pain, swelling and knee locking (when the patient is unable to straighten the leg fully). This can be accompanied by a clicking feeling.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis can be made on the basis of:

- Special tests

- MRI

The diagnosis of a lateral meniscus injury is considered to be fairly certain if three or more of the following findings are present:[5]

– tenderness at one point over the lateral joint line;

– pain in the area of the lateral joint line during hyperextension of the knee joint;

– pain in the area of the lateral joint line during hyperflexion of the knee joint;

– pain during internal rotation of the foot and the lower leg when the knee is flexed at different angles;

– weakened or hypotrophied quadriceps muscle.

Special Tests:

Although there are several tests for a meniscus tear, none can be considered definitive without considerable experience on the part of the examiner. Patient history and the mechanism of injury also provide a major source of information. The most commonly used special tests are...

Magnetic Resonance Imaging:

Meniscal tears can be identified on MRI.

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 McCarty EC, Marx RG, DeHaven KE: Meniscus repair: Considerations in treatment and update of clinical results. Clin Orthop 402:122–134, 2002.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Gray JC: Neural and vascular anatomy of the menisci of the human knee. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 29:23–30, 1999.

- ↑ Zimny ML, Albright DJ, Dabezies E: Mechanoreceptors in the human medial meniscus. Acta Anat (Basel) 133:35–40, 1988.

- ↑ Mine T, Kimura M, Sakka A, et al.: Innervation of nociceptors in the menisci of the knee joint: An immunohistochemical study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 120:201–204, 2000.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Peterson,Renström. SPORTS INJURIES:Their Prevention and Treatment.Third Edition.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Brunker,Khan.Clinical Sports Medicine.3rd Edition.