Lumbar Strain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors '''- [[User:Pieter Jacobs|Pieter Jacobs]] | '''Original Editors '''- [[User:Pieter Jacobs|Pieter Jacobs]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} - [[User:Bo Hellinckx|Bo Hellinckx]] - [[User:Lynn Leemans|Lynn Leemans]] - [[User:Nel Breyne|Nel Breyne]] - [[User:Sarah Harnie|Sarah Harnie]] | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} - [[User:Bo Hellinckx|Bo Hellinckx]] - [[User:Lynn Leemans|Lynn Leemans]] - [[User:Nel Breyne|Nel Breyne]] - [[User:Sarah Harnie|Sarah Harnie]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

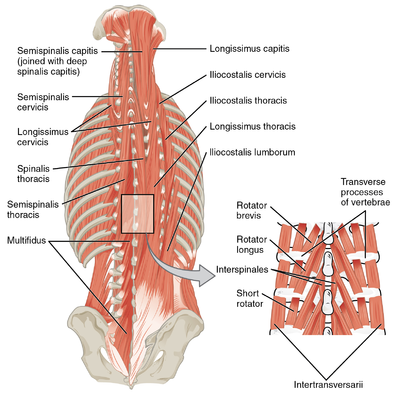

[[File:Muscles of the back.png|Muscles of the back|alt=|right|frameless|399x399px]] | |||

Mechanical back strain is a subtype of [[Low Back Pain|back pain]] where the aetiology is the [[Spine Segmental Assessment|spine]], [[Intervertebral disc|intervertebral discs]], or the surrounding [[Soft Tissue Healing|soft tissues]].<ref name=":4">El Sayed M, Callahan AL. [https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/24813/ Mechanical Back Strain.] StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Mar 25.Available from: https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/24813/<nowiki/>(accessed 28.5.2021)</ref> [[Lumbar]] strain accounts for 70% of mechanical low back pain.<ref name=":0">Will JS, Bury DC, Miller JA. Mechanical low back pain. American family physician. 2018 Oct 1;98(7):421-8.</ref> | |||

This article will focus on muscular lumbar back sprain ie stretch injury or tear of paraspinal [[muscle]]<nowiki/>s and [[Tendon Anatomy|tendons]] in the low back (much of the knowledge of lumbar strain is extrapolated from peripheral muscle strains).<ref name=":1">Scully R, Rao R. [https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-52567-9_103 Lumbar Strain and Lumbar Disk Herniation.] InOrthopedic Surgery Clerkship 2017 (pp. 481-486). Springer, Cham.</ref><ref>Beatty NR, Wyss JF. [https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-50512-1_91 Lumbosacral Muscle Strain 91. Musculoskeletal Sports and Spine Disorders: A Comprehensive Guide.] 2018 Feb 8:395.</ref><ref name=":3">DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain medicine. 2011 Feb 1;12(2):224-33.</ref> | |||

< | * In strains, the muscle is subjected to an excessive [[Tension|tensile]] force leading to the overstraining of the [[Muscle Cells (Myocyte)|myofibres]] and consequently to their rupture near the myotendinous junction.<ref name=":3" /> | ||

* Acute mechanical back strains may be triggered by physical or non-physical activity, with lifting being the most commonly recalled event. However, one-third of patients may not necessarily remember an inciting incident<ref name=":4" />. | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

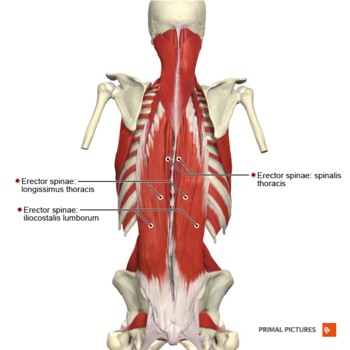

[[File:Muscles of the back erector spinae group Primal.png|right|frameless|350x350px]] | |||

The [[Lumbar|lumbar spine]] consists of a remarkable combination of 5 strong vertebrae; multiple bony elements linked by joint capsules; flexible ligaments/tendons; large muscles; highly sensitive nerves. It is designed to be incredibly strong, protecting the highly sensitive spinal cord and spinal nerve roots. At the same time, it is highly flexible, providing mobility in many different planes including flexion, extension, side bending, and rotation<ref name=" Patel et al.">Patel AT, Ogle AA. Diagnosis and management of acute low back pain. American family physician. 2000 Mar 15;61(6):1779-86.</ref><ref>Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain? Jama. 1992 Aug 12;268(6):760-5.</ref> | |||

< | Lumbar strain can originate in the following muscles<ref>Houglum PA. Therapeutic exercise for athletic injuries. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2001.</ref><ref>Bernard BP, Putz-Anderson V. Musculoskeletal disorders and workplace factors; a critical review of epidemiologic evidence for work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, upper extremity, and low back. 1997</ref><ref name=":5">Meeusen R. 51 Fatigue During Game Play: A Review of Central Nervous System Aspects During Exercise. Science and Football IV. 2001:304.</ref>: M. [[Erector Spinae|erector spinae]] (M. [[Iliocostalis Lumborum|iliocostales]], M [[Longissimus Thoracis|longissimus]], M. [[Spinalis Cervicis|spinalis]]) M semispinales, Mm multifidi, Mm rotatores M. [[Quadratus Lumborum|quadratus lumborum]] M. [[Serratus Posterior]]. | ||

== Etiology == | |||

[[Muscle Strain|Strains]] are defined as tears (partial or complete) of the muscle-tendon unit. | |||

* Muscle strains and tears most frequently result from a violent muscular contraction during an excessively forceful muscular stretch from lifting heavy objects or sudden twisting motions<ref>Kang WW, Kemin S. Clinical observation of the PulStar multiple impulse device in the treatment of acute lumbar strain. China Medicine. 2017 Jul;12(7):1039.</ref>. | |||

* Any posterior spinal muscle and its associated tendon can be involved, although the most susceptible muscles are those that span several joints. | |||

* Acute and chronic lumbar strain pain presentation: Acute pain is most intense 24 to 48 hours after injury. Chronic strains are characterized by continued pain attributable to muscle injury.<ref>Kinkade S. Evaluation and treatment of acute low back pain. American family physician. 2007 Apr 15;75(8):1181-8.</ref> | |||

== Epidemiology == | |||

Greater than 80% of people will suffer from low back pain during their lifetime. The global point prevalence of low back pain is 12 to 33%. There is a higher prevalence among women and people ages 40 to 80 years old.<ref name=":4" /> Exact numbers regarding the international frequency of low back injuries are not known. | |||

* In the United States 7-13% of all sports injuries in intercollegiate athletes are low back injuries. The most common back injuries are muscle strains (60%) and disc injuries (7%). <ref name=":6">Keene JS, Albert MJ, Springer SL, Drummond DS, Clancy JW. Back injuries in college athletes. Journal of spinal disorders. 1989 Sep;2(3):190-5.</ref> | |||

* In France over 50% of French individuals aged 30-64 years had experienced at least 1 day of LBP over the previous 12 months. 17% had suffered LBP for over 30 days in the same 12-month period.<ref>Gourmelen J, Chastang JF, Ozguler A, Lanoë JL, Ravaud JF, Leclerc A. Frequency of low back pain among men and women aged 30 to 64 years in France. Results of two national surveys. InAnnales de réadaptation et de médecine physique 2007 Nov 1 (Vol. 50, No. 8, pp. 640-644). Elsevier Masson.</ref> | |||

* In an African study, the mean LBP point prevalence among adults was 32%, with an average 1-year prevalence of 50% and an average lifetime prevalence of 62%<ref>Louw QA, Morris LD, Grimmer-Somers K. The prevalence of low back pain in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Dec;8(1):105.</ref> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

Acute mechanical back strains may be triggered by physical or non-physical activity, with lifting being the most commonly recalled event. However, one-third of patients may not necessarily remember an inciting incident.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

* The clinical presentation includes pain in the lumbar muscles or nonspecific pain.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* The pain could be exacerbated during standing and twisting motions, with active contractions and passive stretching of the involved muscle increasing the pain.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

* Other symptoms are point tenderness, muscle spasm, possible swelling in and around the involved musculature, a possible lateral deviation in the spine with severe spasm and a decreased range of motion.<ref>Humphreys SC, Eck JC. Clinical evaluation and treatment options for herniated lumbar disc. American family physician. 1999 Feb 1;59(3):575.</ref> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis<ref name=":0" /> == | |||

* | *[[Lumbar Spondylosis|Spondylosis]] | ||

* [[Disc Herniation|Disc herniation]] | |||

* [[Lumbar Compression Fracture|Compression fracture]] | |||

*[[ | *<sup></sup>[[Spinal Stenosis|Spinal stenosis]] | ||

* [[Spondylolisthesis|Spondylolisthesis]] | |||

*[[Ankylosing Spondylitis (Axial Spondyloarthritis)|Ankylosing spondylitis]] | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | |||

In the absence of the [[The Flag System|Red Flags]], no [[Laboratory Tests|laboratory]] or [[Medical Imaging|radiographic studies]] are necessary to diagnose or manage mechanical back strains in the acute setting. | |||

< | * Inflammatory biomarkers, eg erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are helpful for risk stratification of patients with risk factors for infectious spinal pathology or [[Oncology|malignancy]] but have no neurologic deficits on examination. | ||

* Routine imaging for mechanical back strains is not recommended, as many may have incidental abnormal findings unrelated to their pain. | |||

* More advanced imaging is needed in trauma, failure of conservative management, worsening of symptoms, and new neurologic deficits. Plain radiographs and computed tomography are useful when suspecting [[fracture]]<nowiki/>s. | |||

== Examination == | == Examination == | ||

[[Lumbar Assessment]] see link. | |||

== Medical Intervention == | |||

[[File:Taoist Tai Chi class.jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

Management of mechanical back strains depends on the chronicity of symptoms, the patient's comorbidities, and the specific aetiology. The American College of Physicians published an updated guideline in 2017 with recommendations regarding non-invasive options for treating low back pain. | |||

First-line nonpharmacologic therapy: | |||

* For Acute low back pain includes spinal manipulation, [[acupuncture]], massage, and superficial [[Thermotherapy|heat]] application, while first-line pharmacologic therapy for acute low back pain is [[Pain Medications|nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs]] and muscle relaxants. According to the clinical policy by the American College of Emergency Physicians, [[Opioids|opioid]]<nowiki/>s should not be routine pharmaceutical therapy but saved for those whose pain is severe or uncontrolled with other medications. | |||

- | * For [[Chronic Low Back Pain|chronic low back pain]], non-pharmacologic approaches were recommended as the first-line agents, including exercise, [[Tai Chi and the Older Person|tai-chi]], [[yoga]], multidisciplinary rehabilitation, spinal manipulation, [[acupuncture]], psychotherapy, low-level laser therapy, and electromyogram biofeedback. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were again the first-line pharmacologic agents recommended, followed by tramadol and duloxetine as the second-line treatments. Recommendations for opioid therapy are only if the previously mentioned therapies failed and based on an individualized decision to determine if the benefit outweighs the risk.<ref name=":4" /> | ||

== Physical Therapy Management == | |||

Education: Interventions that may aid in injury prevention | |||

* [[Stretching]] exercises at the workplace, appropriate rest breaks, and [[Ergonomics|ergonomic]] modifications. Ergonomic modifications refer to adaptations in the work environment to reduce the physical stress of the employees. | |||

* Educating patients regarding the importance of maintaining proper [[posture]] and correct lifting techniques may aid in prevention. Regular [[Physical Activity|physical activity]] | |||

* [[Smoking Cessation and Brief Intervention|Smoking cessation]] | |||

* Weight loss for [[Obesity|obese patients]] | |||

* Resuming normal physical activity (recent studies have found that continuing ordinary activities within the limits permitted by the pain leads to more rapid recovery than bed rest).<ref name="p1">Malmivaara, M.D., U. Häkkinen et al. The Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain — Bed Rest, Exercises, or Ordinary Activity.the New England Journal of Medicine 1995.</ref> | |||

=== Techniques === | |||

'''[[Cryotherapy|Cold Therapy]]:''' In the acute phase of a lumbar strain [[Cryotherapy|Cold therapy]] should be applied (for a short period up to 48 h)to the affected area to limit the localized tissue inflammation and oedema.<ref name="p4">14.Karnath B. Clinical Signs of Low Back Pain. Hospital Physician. 2003 May. (level of evidence: 5)</ref> <ref name="p5">M.W Van tulder, B.W. Koes. Evidence based handelen bij lage rugpijn. Medicamenteuze behandeling. Bohn staples van Loghum 2004 ( level of evidence: 1A)</ref> | |||

'''TENS and Ultrasound:''' [[Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)|TENS]] and ultrasound are often used to help control pain and decrease muscle spasms <ref name="p6">M. Higgings. Therapeutic exercises. Chapter 19 Rehabilitation of the lumbar spine. Davis Company 2011. (Level of evidence 5)</ref><ref name="p7">L.D Weiss et al. Oxford American handbook of physical medicine and Rehabilitation. 2010 oxford university press. (level of evidence 5)</ref> | |||

'''Stretching:''' Mild [[stretching]] exercises along with limited activity. Stretching Exercises below | |||

| |||

| * [[File: Exercise stretching erector spine.png|thumb]]Single and double knee to chest Lie down on your back with your knees bent and your heels on the floor. Pull your knee or knees as close as you can to your chest, and hold the pose for 10 seconds. Repeat this 3 to 5 times. | ||

* Back stretch Lie on your back, hands above your head. Bend your knees and, keeping your feet on the floor, roll your knees to one side, slowly. Stay at one side for 10 seconds and repeat 3 to 5 times. | |||

* | *Press up Begin by laying flat on the ground (face down). When doing this exercise it is important to keep the hips and legs relaxed and in contact with the floor. Keep your hands in line with your shoulders. Inhale, then exhale and press up using your hands keeping the lower half of your body relaxed. Hold until you need to inhale, then move down, lay flat on the ground to rest, and repeat ten times. | ||

*Kneeling lunge(stretching iliopsoas) | |||

- | *Stretching piriformis | ||

*Stretching quadratus lumborum<ref name="p2">Meeusen R. Sportrevalidatie. Rug- en nekletsels (deel 2) reeks sportrevalidaties. Kluwer.2001. (level of evidence: 5)</ref> | |||

[[File:Strength, plyometric and balance exercises 10 minutes.jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

'''Soft Tissue Manipulation:''' Soft tissue manipulation was found to decrease pain and improve ROM'''.<ref>Li H, Zhang H, Liu S, Wang Y, Gai D, Lu Q, Gan H, Shi Y, Qi W. Rehabilitation effect of exercise with soft tissue manipulation in patients with a lumbar muscle strain. Nigerian Journal of clinical practice. 2017;20(5):629-33.</ref>''' | |||

| * [[Massage]] | ||

* [[Strength Training|Strengthening Exercises]]: Progression of strengthening exercises should begin once the pain and spasm are under control. The muscles requiring the most emphasis are the abdominals, especially the obliques, the trunk extensors and the gluteals. Placing all of the emphasis on rehabilitation specifically on the injured muscle is not beneficial. Training the core stability is an important part in the treatment of a lumbar strain and for the further prevention of low back pain. <ref name="p4" /> | |||

As with all spinal injuries, posture and body mechanics should be assessed and corrected as needed. | |||

== Prognosis == | |||

A Lumbar strain improves within 2 weeks. Normal functions are restored after 4 – 6 weeks. <ref name="p8">Gaetano et al. Lumbar strain back to the basics. Sports medicine, 2005 </ref><sup></sup><br> | |||

< | |||

< | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| Line 188: | Line 119: | ||

| | ||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project | [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | ||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Sports_Injuries]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

[[Category:Muscle strain]] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:29, 9 April 2024

Original Editors - Pieter Jacobs

Top Contributors - Bo Hellinckx, Hannah Willocx, Sarah Harnie, Lynn Leemans, Kim Jackson, Elodie Baele, Lilian Ashraf, Nel Breyne, Wanda van Niekerk, Lucinda hampton, Olajumoke Ogunleye, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Rachael Lowe and Naomi O'Reilly - Bo Hellinckx - Lynn Leemans - Nel Breyne - Sarah Harnie

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Mechanical back strain is a subtype of back pain where the aetiology is the spine, intervertebral discs, or the surrounding soft tissues.[1] Lumbar strain accounts for 70% of mechanical low back pain.[2]

This article will focus on muscular lumbar back sprain ie stretch injury or tear of paraspinal muscles and tendons in the low back (much of the knowledge of lumbar strain is extrapolated from peripheral muscle strains).[3][4][5]

- In strains, the muscle is subjected to an excessive tensile force leading to the overstraining of the myofibres and consequently to their rupture near the myotendinous junction.[5]

- Acute mechanical back strains may be triggered by physical or non-physical activity, with lifting being the most commonly recalled event. However, one-third of patients may not necessarily remember an inciting incident[1].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The lumbar spine consists of a remarkable combination of 5 strong vertebrae; multiple bony elements linked by joint capsules; flexible ligaments/tendons; large muscles; highly sensitive nerves. It is designed to be incredibly strong, protecting the highly sensitive spinal cord and spinal nerve roots. At the same time, it is highly flexible, providing mobility in many different planes including flexion, extension, side bending, and rotation[6][7]

Lumbar strain can originate in the following muscles[8][9][10]: M. erector spinae (M. iliocostales, M longissimus, M. spinalis) M semispinales, Mm multifidi, Mm rotatores M. quadratus lumborum M. Serratus Posterior.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Strains are defined as tears (partial or complete) of the muscle-tendon unit.

- Muscle strains and tears most frequently result from a violent muscular contraction during an excessively forceful muscular stretch from lifting heavy objects or sudden twisting motions[11].

- Any posterior spinal muscle and its associated tendon can be involved, although the most susceptible muscles are those that span several joints.

- Acute and chronic lumbar strain pain presentation: Acute pain is most intense 24 to 48 hours after injury. Chronic strains are characterized by continued pain attributable to muscle injury.[12]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Greater than 80% of people will suffer from low back pain during their lifetime. The global point prevalence of low back pain is 12 to 33%. There is a higher prevalence among women and people ages 40 to 80 years old.[1] Exact numbers regarding the international frequency of low back injuries are not known.

- In the United States 7-13% of all sports injuries in intercollegiate athletes are low back injuries. The most common back injuries are muscle strains (60%) and disc injuries (7%). [13]

- In France over 50% of French individuals aged 30-64 years had experienced at least 1 day of LBP over the previous 12 months. 17% had suffered LBP for over 30 days in the same 12-month period.[14]

- In an African study, the mean LBP point prevalence among adults was 32%, with an average 1-year prevalence of 50% and an average lifetime prevalence of 62%[15]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Acute mechanical back strains may be triggered by physical or non-physical activity, with lifting being the most commonly recalled event. However, one-third of patients may not necessarily remember an inciting incident.[1]

- The clinical presentation includes pain in the lumbar muscles or nonspecific pain.[3]

- The pain could be exacerbated during standing and twisting motions, with active contractions and passive stretching of the involved muscle increasing the pain.[10]

- Other symptoms are point tenderness, muscle spasm, possible swelling in and around the involved musculature, a possible lateral deviation in the spine with severe spasm and a decreased range of motion.[16]

Differential Diagnosis[2][edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

In the absence of the Red Flags, no laboratory or radiographic studies are necessary to diagnose or manage mechanical back strains in the acute setting.

- Inflammatory biomarkers, eg erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are helpful for risk stratification of patients with risk factors for infectious spinal pathology or malignancy but have no neurologic deficits on examination.

- Routine imaging for mechanical back strains is not recommended, as many may have incidental abnormal findings unrelated to their pain.

- More advanced imaging is needed in trauma, failure of conservative management, worsening of symptoms, and new neurologic deficits. Plain radiographs and computed tomography are useful when suspecting fractures.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Lumbar Assessment see link.

Medical Intervention[edit | edit source]

Management of mechanical back strains depends on the chronicity of symptoms, the patient's comorbidities, and the specific aetiology. The American College of Physicians published an updated guideline in 2017 with recommendations regarding non-invasive options for treating low back pain.

First-line nonpharmacologic therapy:

- For Acute low back pain includes spinal manipulation, acupuncture, massage, and superficial heat application, while first-line pharmacologic therapy for acute low back pain is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxants. According to the clinical policy by the American College of Emergency Physicians, opioids should not be routine pharmaceutical therapy but saved for those whose pain is severe or uncontrolled with other medications.

- For chronic low back pain, non-pharmacologic approaches were recommended as the first-line agents, including exercise, tai-chi, yoga, multidisciplinary rehabilitation, spinal manipulation, acupuncture, psychotherapy, low-level laser therapy, and electromyogram biofeedback. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were again the first-line pharmacologic agents recommended, followed by tramadol and duloxetine as the second-line treatments. Recommendations for opioid therapy are only if the previously mentioned therapies failed and based on an individualized decision to determine if the benefit outweighs the risk.[1]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Education: Interventions that may aid in injury prevention

- Stretching exercises at the workplace, appropriate rest breaks, and ergonomic modifications. Ergonomic modifications refer to adaptations in the work environment to reduce the physical stress of the employees.

- Educating patients regarding the importance of maintaining proper posture and correct lifting techniques may aid in prevention. Regular physical activity

- Smoking cessation

- Weight loss for obese patients

- Resuming normal physical activity (recent studies have found that continuing ordinary activities within the limits permitted by the pain leads to more rapid recovery than bed rest).[17]

Techniques[edit | edit source]

Cold Therapy: In the acute phase of a lumbar strain Cold therapy should be applied (for a short period up to 48 h)to the affected area to limit the localized tissue inflammation and oedema.[18] [19]

TENS and Ultrasound: TENS and ultrasound are often used to help control pain and decrease muscle spasms [20][21]

Stretching: Mild stretching exercises along with limited activity. Stretching Exercises below

- Single and double knee to chest Lie down on your back with your knees bent and your heels on the floor. Pull your knee or knees as close as you can to your chest, and hold the pose for 10 seconds. Repeat this 3 to 5 times.

- Back stretch Lie on your back, hands above your head. Bend your knees and, keeping your feet on the floor, roll your knees to one side, slowly. Stay at one side for 10 seconds and repeat 3 to 5 times.

- Press up Begin by laying flat on the ground (face down). When doing this exercise it is important to keep the hips and legs relaxed and in contact with the floor. Keep your hands in line with your shoulders. Inhale, then exhale and press up using your hands keeping the lower half of your body relaxed. Hold until you need to inhale, then move down, lay flat on the ground to rest, and repeat ten times.

- Kneeling lunge(stretching iliopsoas)

- Stretching piriformis

- Stretching quadratus lumborum[22]

Soft Tissue Manipulation: Soft tissue manipulation was found to decrease pain and improve ROM.[23]

- Massage

- Strengthening Exercises: Progression of strengthening exercises should begin once the pain and spasm are under control. The muscles requiring the most emphasis are the abdominals, especially the obliques, the trunk extensors and the gluteals. Placing all of the emphasis on rehabilitation specifically on the injured muscle is not beneficial. Training the core stability is an important part in the treatment of a lumbar strain and for the further prevention of low back pain. [18]

As with all spinal injuries, posture and body mechanics should be assessed and corrected as needed.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

A Lumbar strain improves within 2 weeks. Normal functions are restored after 4 – 6 weeks. [24]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 El Sayed M, Callahan AL. Mechanical Back Strain. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Mar 25.Available from: https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/24813/(accessed 28.5.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Will JS, Bury DC, Miller JA. Mechanical low back pain. American family physician. 2018 Oct 1;98(7):421-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Scully R, Rao R. Lumbar Strain and Lumbar Disk Herniation. InOrthopedic Surgery Clerkship 2017 (pp. 481-486). Springer, Cham.

- ↑ Beatty NR, Wyss JF. Lumbosacral Muscle Strain 91. Musculoskeletal Sports and Spine Disorders: A Comprehensive Guide. 2018 Feb 8:395.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain medicine. 2011 Feb 1;12(2):224-33.

- ↑ Patel AT, Ogle AA. Diagnosis and management of acute low back pain. American family physician. 2000 Mar 15;61(6):1779-86.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain? Jama. 1992 Aug 12;268(6):760-5.

- ↑ Houglum PA. Therapeutic exercise for athletic injuries. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2001.

- ↑ Bernard BP, Putz-Anderson V. Musculoskeletal disorders and workplace factors; a critical review of epidemiologic evidence for work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, upper extremity, and low back. 1997

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Meeusen R. 51 Fatigue During Game Play: A Review of Central Nervous System Aspects During Exercise. Science and Football IV. 2001:304.

- ↑ Kang WW, Kemin S. Clinical observation of the PulStar multiple impulse device in the treatment of acute lumbar strain. China Medicine. 2017 Jul;12(7):1039.

- ↑ Kinkade S. Evaluation and treatment of acute low back pain. American family physician. 2007 Apr 15;75(8):1181-8.

- ↑ Keene JS, Albert MJ, Springer SL, Drummond DS, Clancy JW. Back injuries in college athletes. Journal of spinal disorders. 1989 Sep;2(3):190-5.

- ↑ Gourmelen J, Chastang JF, Ozguler A, Lanoë JL, Ravaud JF, Leclerc A. Frequency of low back pain among men and women aged 30 to 64 years in France. Results of two national surveys. InAnnales de réadaptation et de médecine physique 2007 Nov 1 (Vol. 50, No. 8, pp. 640-644). Elsevier Masson.

- ↑ Louw QA, Morris LD, Grimmer-Somers K. The prevalence of low back pain in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Dec;8(1):105.

- ↑ Humphreys SC, Eck JC. Clinical evaluation and treatment options for herniated lumbar disc. American family physician. 1999 Feb 1;59(3):575.

- ↑ Malmivaara, M.D., U. Häkkinen et al. The Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain — Bed Rest, Exercises, or Ordinary Activity.the New England Journal of Medicine 1995.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 14.Karnath B. Clinical Signs of Low Back Pain. Hospital Physician. 2003 May. (level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ M.W Van tulder, B.W. Koes. Evidence based handelen bij lage rugpijn. Medicamenteuze behandeling. Bohn staples van Loghum 2004 ( level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ M. Higgings. Therapeutic exercises. Chapter 19 Rehabilitation of the lumbar spine. Davis Company 2011. (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ L.D Weiss et al. Oxford American handbook of physical medicine and Rehabilitation. 2010 oxford university press. (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Meeusen R. Sportrevalidatie. Rug- en nekletsels (deel 2) reeks sportrevalidaties. Kluwer.2001. (level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ Li H, Zhang H, Liu S, Wang Y, Gai D, Lu Q, Gan H, Shi Y, Qi W. Rehabilitation effect of exercise with soft tissue manipulation in patients with a lumbar muscle strain. Nigerian Journal of clinical practice. 2017;20(5):629-33.

- ↑ Gaetano et al. Lumbar strain back to the basics. Sports medicine, 2005