Emotional and Psychological Reactions to Amputation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

In contrast, some amputees adapt '''effective coping styles that''' result from self-efficacy, using humor, making plans and visualizing the future, and actively seeking help to solve problems. [http://www.selfcareinsocialwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/WAYS-OF-COPING-was-designed-by-Lazarus-and-Folkman.pdf The Way of Coping Check-List] can be used to screen for patients at high risk for adjusting poorly to amputation and for having further negative sequelae. | In contrast, some amputees adapt '''effective coping styles that''' result from self-efficacy, using humor, making plans and visualizing the future, and actively seeking help to solve problems. [http://www.selfcareinsocialwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/WAYS-OF-COPING-was-designed-by-Lazarus-and-Folkman.pdf The Way of Coping Check-List] can be used to screen for patients at high risk for adjusting poorly to amputation and for having further negative sequelae. | ||

== | ==== '''STAGES OF ADAPTATION''' ==== | ||

It is useful to think of the process of adaptation as occurring in four stages<ref>Moore WS, Malone SJ (eds): Lower Extremity Amputation.Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1989, chap 26.</ref>: | |||

'''Preoperative Stage''' | |||

Among amputees for whom there is ample opportunity to be prepared for surgery, approximately a third to a half welcome the amputation as a signal that suffering will be relieved and a new phase of adjustment can begin. Along with this acceptance, there may be varying degrees of anxiety and concern. Such concerns fall into two large groups: | |||

1-''practical'' issues as the loss of function, loss of income, pain, difficulty in adapting to a prosthesis, and cost of ongoing treatment. | |||

''2-symbolic'' concerns such as changes in appearance, losses in sexual intimacy, perception by others, and disposal of the limb. | |||

Most individuals informed of the need for amputation go through the early stages of a grief reaction, which may not be completed until well after their discharge from the hospital. | |||

'''Immediate Postoperative Stage''' | |||

This period may lasts from hours to days, depending on the reason for the amputation and the condition of the residual limb. | |||

Psychological reactions noted in this phase are concerns about safety, fear of complications and pain, and in some instances, loss of alertness and orientation. In general, those who sustain the amputation after a period of preparation react more positively than do those who sustain it after trauma or accident. Most individuals are, to a certain degree, "numb," partly as a result of the anesthesia and partly as a way of handling the trauma of loss. For those who have suffered considerable pain before the surgery, the amputation may bring much-needed relief. | |||

'''In-Hospital Rehabilitation''' | |||

The most critical phase and presents the greatest challenges to the patient, the family, and the amputation team. Initially, the patient is concerned about safety, pain, and disfigurement. Later on, the emphasis shifts to social reintegration and vocational adjustment. Some individuals in this phase experience and express various kinds of denial shown through bravado and competitiveness. A few resort to humor and minimization. Mild euphoric states may be reflected in increased motor activity, racing through the corridors in wheelchairs, and over talkativeness.Eventually sadness sets in. | |||

'''At-Home Rehabilitation''' | |||

It is during this phase that the full impact of the loss becomes evident. A number of individuals experience a "second realization," with attendant sadness and grief.Varying degrees of regressive behavior may be evident, such as a reluctance to give up the sick role, a tendency to lean on others beyond what is justified by the disability, and a retreat to "baby talk." Some resent any pressure put upon them to resume normal functioning. Others may go to the other extreme and vehemently reject any suggestion that they might be disabled or require help in any way. An excessive show of sympathy generally fosters the notion that one is to be pitied. In this phase, three areas of concern come to the fore: return to gainful employment, social acceptance, and sexual adjustment. Of immense value in all of these matters is the availability of a relative or a significant other who can provide support without damaging self-es-teem. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 15:27, 29 March 2018

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Tips for writing this page:

Aim:

- To enable the reader to be aware of the common emotional and psychological reactions to amputation and demonstrate an understanding of the stages of the grieving process (may ned to create another separate page for the grieving process)

A quick word on content:

Content criteria:

- Evidence based

- Referenced

- Include images and videos

- Include a list of open online resources that we can link to

Example content:

Original Editor - Add a link to your Physiopedia profile here.

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Kim Jackson, Admin, Tarina van der Stockt, Lauren Lopez, Claire Knott, Amanda Ager, Jess Bell and Jorge Rodríguez Palomino

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Amputation proposes multi-directional challenges. It affects function, sensation and body image. The psychological reactions vary greatly and depend on many factors and variable. In most cases, the predominant experience of the amputee is one of loss: not only the obvious loss of the limb, but also resulting losses in function, self-image, career and relationships[1].

Many of the psychological reactions may be transient, some are helpful and constructive, others less so, and a few may require further action (e.g. psychiatric assessment in the case of psychosis)[1].

About 30% of amputees are troubled by depression[1]. Psychological morbidity, decreased self esteem, distorted body image, increased dependency and significant levels of social isolation are also observed in short and long-term follow up after amputation[2][3].

Psychological Reactions to Amputation[edit | edit source]

Immediate reaction to the news of amputation depends on whether the amputation was planned, occurred within the context of chronic medical illness or necessitated by a sudden onset of infection or trauma[4].

After learning that amputation may be required, anxiety often alternates with depression. This anxiety may be generalized (e.g., manifest by jitteriness, a decreased ability to sleep, silent rumination, and social withdrawal) or result in disturbed sleep and irritability. Anxiety may be directed toward the fate of the limb that will be removed[5], as well as about the prospect of phantom limb pain, which many patients (who know of other amputees) may be familiar with[4]. Findings by Parkes [17] also found that in first year 25% amputees suffer from depression, feeling of insecurity, self consciousness and restlessness18].

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) appears to be more common in amputees following combat, accidental injury, burn and suicidal attempts[6].In contrast, PTSD is relatively rare (< 5%) among amputees whose surgery follows a chronic illness[7].

Cosmetic appearance appears to play as great a role in psychological sequelae of amputation.Body image, defined as ‘the individual’s psycho-logical picture of himself’[8] is disrupted when a limb is amputated[1]. A number of of body image-related problems may be frequently experienced following amputation such as anxiety and sexual impairment and/or dysfunction[8] (77% in males and 38% in females)[1].

The reaction to amputation may not always be negative. When amputations occur after a long period of illness and loss of function, the patient may already have gone through a period of grieving and have no need to grieve again for the amputation[1].

A study[9] that investigated positive thoughts in amputation showed that 56% of people thought about their amputated limb. People with bilateral or a trans-femoral amputation were more likely to think about their amputated limb than people with a trans-tibial amputation. This may refer to the fact that the more of a limb that is lost the greater is the difficultly in restoring physical functioning. Thinking about the amputated limb may arise questions (e.g. what happened to the amputated limb? What life would have been like if they had not lost a limb? Why me? What the future held as a result of having a limb, What if?), and specific emotions (missing the limb, wish that they did not have an artificial limb, that they had their limb(s) back or that the accident had not happened and concern about getting employment).

In the same study, 46% considered that something good had happened as a result of the amputation. Participants stated many reasons as good things that happened following amputation such as: the Independence given to them by the amputation and the prosthesis, subsequent change in their attitude of life, improved coping abilities, financial benefits, elimination of pain and that amputation was a character building for some of them. Furthermore, finding positive meaning was significantly associated with more favorable physical capabilities and health ratings, lower levels of Athletic Activity Restriction and higher levels of Adjustment to Limitation[9].

Coping Styles[edit | edit source]

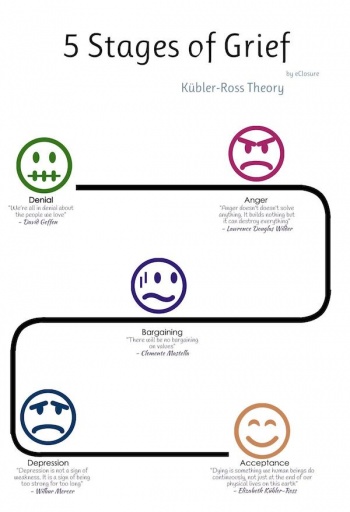

When there is time to think about impending loss, classic stages of grief may be experienced[4][10]:

- Denial; often manifest as refusal to engage in discussion or to ask basic questions about the planned procedure

- Anger: which may be directed towards the medical team, with expressions of being cheated or tricked into agreeing to an amputation

- Bargaining: by attempting to forestall the surgery or to delay it indefinitely for a myriad of reasons such as ‘’I’m too tired I don’t want to go through with any major surgery’’

- Depression: taking the form of learned helplessness’’ feeling of passivity, and being overwhelmed

- Acceptance: which may not be reached until the patient is into the rehabilitation process.

A minority of amputees experience denial in relation to accepting their impairment (i.e. the reality that their limb is missing). However, phantom sensation may play a role in reinforcing the denial. This degree of denial may lead to serious problems. Such a disconnection with reality may indicate some underlying psychosis and if this state persists for more than a few days and the amputee is not responding to counseling, a psychiatric assessment should be requested[1].

Maladaptive coping styles can be classified as overcompensation, surrender, or avoidance. 44 Overcompensation can take the form of hostility, excessive self-assertion (e.g., by refusing help that is needed), recognition seeking, manipulation, or obsessiveness (e.g., by becoming preoccupied with smaller details of care at the expense of regaining whatever enjoyment of life is still possible). Surrender may take the form of clinging to the sick role and continuing to demand a high level of nursing care, while refusing to undergo rehabilitation. Avoidance may result in psychological withdrawal, addictive self-soothing, or social withdrawal[4].

Mutilation anxiety is closely related to one's coping style and to the experience of pain. Prior to amputation, as part of the course of prevention (of both chronic vascular disease, as well as accidental injury), mutilation anxiety can be used to motivate patients for self-care and medical compliance. After amputation, mutilation anxiety may be a factor in referring a patient for psychotherapy or treatment of anxiety with medications. Mutilation anxiety may also affect the sexual function of a patient[11]. Men have reported feeling castrated by amputation, while women are more likely to report feeling sexual guilt and “punished” for some real or imagined transgression by amputation[12]. Medical management of fatigue, pain, and cosmesis of the stump can further alleviate these difficulties during the rehabilitation process[4].

In contrast, some amputees adapt effective coping styles that result from self-efficacy, using humor, making plans and visualizing the future, and actively seeking help to solve problems. The Way of Coping Check-List can be used to screen for patients at high risk for adjusting poorly to amputation and for having further negative sequelae.

STAGES OF ADAPTATION[edit | edit source]

It is useful to think of the process of adaptation as occurring in four stages[13]:

Preoperative Stage

Among amputees for whom there is ample opportunity to be prepared for surgery, approximately a third to a half welcome the amputation as a signal that suffering will be relieved and a new phase of adjustment can begin. Along with this acceptance, there may be varying degrees of anxiety and concern. Such concerns fall into two large groups:

1-practical issues as the loss of function, loss of income, pain, difficulty in adapting to a prosthesis, and cost of ongoing treatment.

2-symbolic concerns such as changes in appearance, losses in sexual intimacy, perception by others, and disposal of the limb.

Most individuals informed of the need for amputation go through the early stages of a grief reaction, which may not be completed until well after their discharge from the hospital.

Immediate Postoperative Stage

This period may lasts from hours to days, depending on the reason for the amputation and the condition of the residual limb.

Psychological reactions noted in this phase are concerns about safety, fear of complications and pain, and in some instances, loss of alertness and orientation. In general, those who sustain the amputation after a period of preparation react more positively than do those who sustain it after trauma or accident. Most individuals are, to a certain degree, "numb," partly as a result of the anesthesia and partly as a way of handling the trauma of loss. For those who have suffered considerable pain before the surgery, the amputation may bring much-needed relief.

In-Hospital Rehabilitation

The most critical phase and presents the greatest challenges to the patient, the family, and the amputation team. Initially, the patient is concerned about safety, pain, and disfigurement. Later on, the emphasis shifts to social reintegration and vocational adjustment. Some individuals in this phase experience and express various kinds of denial shown through bravado and competitiveness. A few resort to humor and minimization. Mild euphoric states may be reflected in increased motor activity, racing through the corridors in wheelchairs, and over talkativeness.Eventually sadness sets in.

At-Home Rehabilitation

It is during this phase that the full impact of the loss becomes evident. A number of individuals experience a "second realization," with attendant sadness and grief.Varying degrees of regressive behavior may be evident, such as a reluctance to give up the sick role, a tendency to lean on others beyond what is justified by the disability, and a retreat to "baby talk." Some resent any pressure put upon them to resume normal functioning. Others may go to the other extreme and vehemently reject any suggestion that they might be disabled or require help in any way. An excessive show of sympathy generally fosters the notion that one is to be pitied. In this phase, three areas of concern come to the fore: return to gainful employment, social acceptance, and sexual adjustment. Of immense value in all of these matters is the availability of a relative or a significant other who can provide support without damaging self-es-teem.

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Therapy for Amputees: Third Edition by Barbara Engstrom MCSP DipMgt & Catherine Van de Ven MCSP

- ↑ Thompson D M, Haran D 1983 Living with an amputation: the patient. International Rehabilitation Medicine 5:165–169

- ↑ Srivastava, K., Saldanha, D., Chaudhury, S., Ryali, V., Goyal, S., Bhattacharyya, D. and Basannar, D. (2010). A Study of Psychological Correlates after Amputation. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 66(4), pp.367-373.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Bhuvaneswar, C. G., Epstein, L. A., & Stern, T. A. (2007). Rounds in the General Hospital: Reactions to Amputation: Recognition and Treatment, 9(4), 303–308.

- ↑ NOBLE, D., PRICE, D. and GILDER, R. (1954). PSYCHIATRIC DISTURBANCES FOLLOWING AMPUTATION. American Journal of Psychiatry, 110(8), pp.609-613.

- ↑ Fukunishi I, Sasaki K, Chishima Y, Anze M, Saijo M General hospital psychiatry, vol. 18, issue 2 (1996) pp. 121-7

- ↑ Cavanagh, S., Shin, L., Karamouz, N. and Rauch, S. (2006). Psychiatric and Emotional Sequelae of Surgical Amputation. Psychosomatics, 47(6), pp.459-464.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Henker III, F. (1979). Body-image conffict following trauma and surgery. Psychosomatics, 20(12), pp.812-820.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gallagher, P., & Maclachlan, M. (2000). Prosthetics and Orthotics International. https://doi.org/10.1080/03093640008726548

- ↑ PARKES, C. (1975). Psycho-social Transitions: Comparison between Reactions to Loss of a Limb and Loss of a Spouse. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 127(3), pp.204-210.

- ↑ Shell, J. and Miller, M. (1999). The Cancer Amputee and Sexuality. Orthopaedic Nursing, 18(5), pp.53???64.

- ↑ Hogan, R. (1985). Human sexuality. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- ↑ Moore WS, Malone SJ (eds): Lower Extremity Amputation.Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1989, chap 26.