Facet Joint Syndrome

Original Editors - Jonas Vangindertael

Top Contributors - Aarti Sareen, Emma Guettard, Jonas Vangindertael, Admin, Liza De Dobbeleer, Niels Cloet, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Rachael Lowe, Anke Jughters, Laura Ritchie, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Claire Knott, Scott Buxton, Nel Breyne and Joanne Garvey

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Facet joint disease is a condition in which the facet joints (also termed zygapophyseal joints) of the spine become a source of pain.

- This is a very common disease process (its prevalence increasing with age) and is a common source of disability with significant economic impact.

- Chronic low back pain often results from facet joint disease, with a prevalence of 15 to 41%[1]

Facet syndrome is an articular disorder related to the facet joints and their innervations, and produces both local and radiating pain.

- 55% of facet syndrome cases occur in cervical vertebrae, and 31% in lumbar.[2]

- Neck pain due to cervical facet joint involvement is known as cervical facet syndrome and low back pain due to lumbar facet joint involvement is known as lumbar facet syndrome.

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

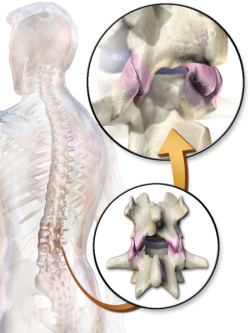

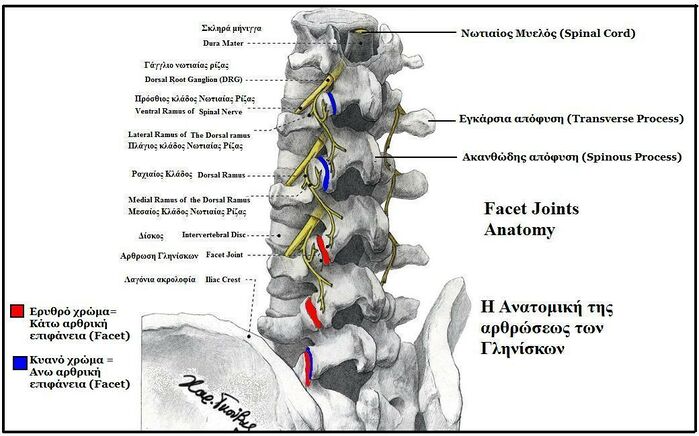

Facet joints

- Form from the superior and inferior articular processes of two adjacent vertebrae.

- In each spinal motion segment there are two facet joints.

- Are synovial joints - a fibrous capsule encompasses the bone and articulating cartilage and is continuous with the periosteum.

- Contains synovial fluid which is kept in place by an inner membrane.

- Function - allow for flexion and extension of the spine while limiting rotation and preventing the vertebrae from slipping over each other.

The sensory nerve of these joints is the medial branch of the dorsal spinal ramus[1].

Further the detailed anatomy and clinical anatomy can be learned from here .

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The lifetime adult prevalence of low back pain in the United States is 65 to 80%.

- Facet joint syndrome is more common in the elderly since changes at the joints develop with aging.

- Having a history of doing heavy work before age 20 increases the likelihood of developing facet joint osteoarthritis.

- Obesity also largely contributes to osteoarthritis; thus, it is likely a contributing factor in the development of facet joint disease.

- Spondylolisthesis caused by degeneration is most often caused by facet joint osteoarthritis, and typically occurs at the L4-L5 level.

- Spondylolisthesis that presents in a younger population (30 to 40years old) is due to congenital abnormalities, stress, or acute fractures.

- Cervical facet disease and pain have a prevalence rate of 29 to 60% following whiplash injuries; although overall trauma is still a rare cause[1].

In a study from Eubanks et al[3]. there was a prevalence rates of facet arthrosis (on 647 cadaveric lumbar spines):

- 57% of samples between 20 and 29 years of age

- 93% of the samples 40-49 years of age

- 100% of the samples showed prominent facet arthrosis by the age of 60

- The highest prevalence and moreover, the greatest severity of arthrosis, were found at L4–L5. [4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The most common cause of facet joint disease is degeneration of the spine, also known as spondylosis.

Causes:

- When the degeneration of the joint is secondary to natural wearing and abnormal body mechanics the condition is known as osteoarthritis (OA). The pathophysiology of OA is not entirely understood but is a complex one involving various cytokines and proteolytic enzymes as well as personal risk factors.

- Secondary to trauma from eg injury or sporting activities.

- Secondary to Inflammatory conditions such eg rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis (contribute due to the inflammation of the synovium).

- Subluxation of the facet joints due to spondylolisthesis can also contribute to the development of facet joint disease.

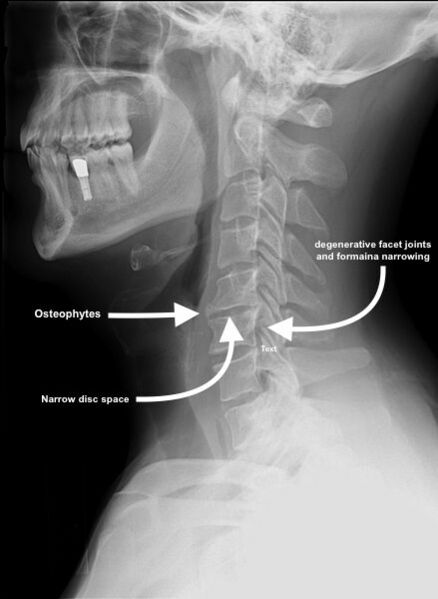

Those with facet joint disease show signs of cartilage erosion and inflammation, which can lead to pain. The body will also undergo several physical changes in response to this process.

- Ligaments eg the ligamentum flavum, can become thickened and hypertrophic.

- New bone formation around the joint can occur with the development of osteophytes or “bone spurs.”

- There can also be an increase in the subchondral bone volume with hypomineralization[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Facet joint pain is felt locally as a unilateral back pain, which when severe can spread down the entire limb. The source of pain must be confirmed by clinical examination. The joint capsule is more likely to generate pain than the articular cartilage or the synovium. All of the lumbar facet joints are capable of producing pain that can refer to the groin (this is more common with lower facet joint pathology).[5]

Cervical facet syndrome includes following symptoms:

- Axial neck pain (rarely radiating past the shoulders), most common unilaterally

- Pain with and/or limitation of extension and rotation

- Tenderness upon palpation

- Radiating pain locally or into the shoulders or upper back, and rarely radiate in the front or down an arm or into the fingers as a herniated disc might.

Lumbar facet syndrome can be characterised by following symptoms:[6]

- Pain or tenderness in lower back.

- Local tenderness/stiffness alongside the spine in the lower back.

- Pain, stiffness or difficulty with certain movements (such as standing up straight or getting up from a chair.

- Pain upon hyperextension

- Referred pain from upper lumbar facet joints can extend into the flank, hip and upper lateral thigh

- Referred pain from lower lumbar facet joints can penetrate deep into the thigh, laterally and/or posteriorly

- L4-L5 and L5-S1 facet joints can refer pain extending into the distal lateral leg, and in rare instances to the foot[5]

[7]

Additionally, facet joint syndrome is more common in the elderly since changes at the joints develop with aging. [8] Acute episodes of lumbar and cervical facet joint pain are typically intermittent, generally unpredictable, and occur a few times per month or per year. Typically, there will be greater aggravation of symptoms with lumbar extension than lumbar flexion. In lumbar cases, standing may be somewhat limited but sitting and riding in a car are most provocative. Recurrent painful episodes can be frequent and quite unpredictable in both timing and extent. Improper diagnosis can result in patients that are left with the notion that this is a psychosomatic problem.[9]

Osteoarthritis is only one of many inflammatory processes that affect the facet joint. Other inflammatory conditions include rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, synovial impingement, meniscoid entrapment, chondromalacia facetae, pseudogout, synovial inflammation, villonodular synovitis, and acute chronic infection.[5] Intrafacetal synovial cysts can be a source of pain because of distension and pressure on adjacent pain-generating structures, calcification, and asymmetrical facet hypertrophy.[6]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Sciatica

- Hip osteoarthritis

- Sacroiliac impingement

- Lumbar radiculopathy

- Myofascial pain

- Compression fractures

- Disc herniation

- Osteophytes

- Rheumatoid arthritis[1]

Much has been written about the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar facet joint pain.

- A review of the relevant literature found conflicting evidence in support of a relationship between radiographic facet joint abnormalities and facet-mediated pain. This may partly be due to the poor reliability of the lumbar “facet joint syndrome” diagnosis given to patients presenting with primary lower back pain complaints.

- The“pseudoradicular” referral patterns of the lumbar facet joints may mimic the pain felt from a herniated disc and may make differentiating between the two conditions difficult.[10]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic medial branch blocks are considered the gold standard approach to diagnose facet joint pain. A positive response to a set of 2 diagnostic blocks done on two separate occasions at two or more levels can confirm the source of pain. High false-positive responses are more likely to occur if only 1 level is blocked.

It is often challenging to isolate facet joint disease as the sole cause of a patient’s complaint of neck or back pain.

- Imaging has not been proved to have much if any diagnostic validity.

- X-ray, CT, and MRI may show degeneration, joint space narrowing, facet joint hypertrophy, joint space calcification, and osteophytes; however, these findings may be present in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

- Data shows that 89% of patients in the 60 to 69 years of age population studied have facet joint osteoarthritis[1]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Finger-floor test

- Lumbar spine rotation

- Schober's index

- Visual analog scale [11]

Examination[edit | edit source]

- Inspection

Inspection should include an evaluation of paraspinal muscle fullness or asymmetry, increase or decrease in lumbar lordosis, muscle atrophy, or posture asymmetry. Patients with chronic facet syndrome may have flattening of the lumbar lordotic curves and rotation or lateral bending at the sacroiliac joint or thoracolumbar area.

- Palpation

The examiner should palpate along the paravertebral regions and directly over the transverse processes because the facet joints are not truly palpable. This is performed in an attempt to localize and reproduce any point tenderness, which is usually present with facet joint–mediated pain. In some cases, facet joint–mediated pain may radiate to the gluteal or posterior thigh regions.

- Range of motion

Range of motion should be assessed through flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation. With facet joint–mediated low back pain, pain is often increased with hyperextension or rotation of the lumbar spine, and it might be either focal or radiating.

- Flexibility

Inflexibility of the pelvic musculature can directly impact the mechanics of the lumbosacral spine. With facet joint pathology, the clinician may find an abnormal pelvic tilt and rotation of the hip secondary to tight hamstrings, hip rotators, and the quadratus, but these findings are nonspecific and can be found in patients with other causes of low back pain.

- Sensory examination

Sensory examination (light touch and pinprick in a dermatomal distribution) findings are usually normal in persons with facet joint pathology.

- Muscle stretch reflexes

Patients with facet joint–mediated LBP usually have normal muscle stretch reflexes. Radicular findings are usually absent unless the patient has nerve root impingement from bony overgrowth or a synovial cyst. Side-to-side asymmetry should lead one to consider possible nerve root impingement.

- Muscle strength

Manual muscle testing is important to determine whether weakness is present and whether the distribution of weakness corresponds to a single root, multiple roots, or a peripheral nerve or plexus.

Typically, manual muscle testing results are normal in persons with facet joint pathology; however, subtle weakness of the muscles of the pelvic girdle may contribute to pelvic tilt abnormalities. This subtle weakness may be appreciated with trunk, pelvic, and lower-extremity extension asymmetry.

Special test for LBA due to facet joint[12] include Kemp’s test and Springing test.

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative management is used as first-line therapy to treat facet-mediated pain.

- Anti-inflammatory medications, weight loss, muscle relaxers, physical therapy, and massage are therapies used in conjunction with one another as a multimodal approach to treating the pain.

When conservative measures fail, interventional procedures are considered to reduce pain, improve functionality and reduce side effects from medications.

Image: Medial Branch Nerve Block Injection, Chronic Pain Treatment

Medial branch blocks (Radiofrequency ablation uses heat to temporarily destroy the medial branch of the sensory nerve,providing a reduction of pain).

- Diagnostic medial branch blocks are often performed to confirm the generation of the pain is from the facet joints. If a patient has a positive response to a set of two diagnostic blocks, radiofrequency ablation can then be done to ablate the medial branch nerves.

- Improved function and decreased pain have been shown to last from 6 to 12 months following lumbar medial branch radiofrequency ablation.

- The procedures mentioned above are done usually under local anesthesia and fluoroscopic guidance.

- Because nerves regenerate eventually, the procedure is repeatable when the patient’s pain returns, typically in 6 to 12 months.

There are currently no guidelines available to support arthrodesis when interventional procedures fail to provide pain relief. Surgery may be indicated for grade I or grade II spondylolisthesis; however, this is not first-line management and may not result in the reduction of pain.[1]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy and core strengthening exercises can strengthen the spine and reduce the stress on the facet joints. The initial treatment for acute facet joint pain is focused on:

- Education

Patient education includes explaining the problem or their associated impairment to the patient, without making them anxious. It includes pain education mostly therefore a diplomatic approach is recommended in order to prevent the patient from catastrophizing. During the therapy, it’s also important that the therapist gives advice/instructions or cues about the patient’s posture and placement of his body to make corrections during everyday activities. The patient must learn to take postures that will not provoke or exacerbate the symptoms.[9]

- Relative rest

Bed rest beyond 2 days isn’t recommended as it can have undesirable effects on bones, connective tissues, muscles and the cardiovascular system.

The patient is encouraged to limit activity on days when the symptoms are not tolerable, but should never be completely inactive. Therapist must strive to influence the patient to be as active as possible.[9]

- Reducing lumbar lordosis

Therefore it is important to reduce excessive lumbar lordosis with exercise because excessive lordosis increases loading on the posterior aspect of the spine, including the z-joints. To achieve this, the patient should be taught pelvic manoeuvres to reduce the degree of lumbar lordosis. These pelvic tilt exercises can be performed in multiple positions such as sitting, standing with knees bent or straight legs. [12]

- Pain relief

Bronfort G. et al studied the relative efficacy of three different treatments for chronic low back pain. They comprised followed combinations: spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) combined with trunk strengthening exercises (TSE) vs. SMT combined with trunk stretching exercises and SMT combined with TSE vs. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy combined with TSE. During 11 weeks (5 weeks under supervising and 6 weeks alone) they examined: patient-rated low back pain, disability and functional health status. Their conclusion was that each of the three therapeutic regimens was associated with similar and clinically important improvements. For the management of facet joint syndrome, trunk exercise in combination with SMT or NSAID therapy seemed to be beneficial and worthwhile.[13]

Spinal manipulation is being used for both short- and long-term pain relief.[12]

- Exercises

Other scientific sources recommend treating facet joint syndrome with heat, cryotherapy and mobilizations. These techniques appear to have a relaxing effect on the muscles. As the muscles relax, the nociceptive information will decrease. While these techniques have clear advantages, they generally only attain a temporary pain relief as they are often not a final solution to treat facet joint syndrome.

[15]

Gerard et al.[16] argue that once the painful symptoms are controlled, stretching and strengthening exercises can be initiated.[9] For the stretch, the focus should be on the muscles that create excessive anterior tilt of the pelvis. Stretching should not be not limited to just these muscles because all the muscles articulating to the lumbar spine and pelvic girdle may be imbalanced, and regular stretching can help restore productive mechanics to the lumbar spine and pelvis. Therefore, stretching programs should also include the hamstrings, quadriceps, hip abductors, gluteals, and abdominals. Stretching through dynamic postural motions (for example yoga postures) can be especially helpful because the motions can restore balance to the muscles of the lumbar spine and pelvic girdle.[12] These exercises are eventually incorporated into a more extensive rehabilitation program, which includes spine stabilization exercises The objective of these exercises is to teach the patient how to find and maintain a neutral spine throughout everyday activities.[9]

In the final phase of the rehabilitation, eccentric muscle strengthening exercises and dynamic exercises are added to the program. These are to be performed in a functional manner and in functional planes. All exercises were performed in the treatment room under the supervision of a physical therapist with technical knowledge. The therapist put each patient into the appropriate position to achieve the correct posture and muscle contraction. An important focus of the exercise therapy should be on stabilization therapy. They are aimed to strengthen the deep lumbar stabilizing muscles: the transversus abdominis, lumbar multifidi, and internal obliques. A series of 16 exercises should be performed in the same order, as described by Moon et al. Before each exercise, the physical therapist gave detailed verbal explanation and visual instructions (pictures), regarding the start and end positions. All exercises were conducted according to the following specific principles: breathe in and out, gently and slowly draw in your lower abdomen below your umbilicus without moving your upper stomach, back or pelvis"; resulting in a situation referred to as hollowing. Subjects practiced "hollowing" with a therapist providing verbal instruction and tactile feedback until they were able to perform the manoeuvre in a satisfactory manner. In addition, a "bulging" of the multifidus muscle should have been felt by the therapist when the fingers were placed on either side of the spinous processes of the L4 and L5 vertebrae, directly over the belly of this muscle. These feedback techniques provided by precise palpitation of the appropriate muscles, ensure effective muscle activation.[5]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Curtis L, Shah N, Padalia D. Facet Joint Disease. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Apr 20.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541049/(accessed 15.6.2021)

- ↑ Varlotta GP, Lefkowitz TR, Schweitzer M, Errico TJ, Spivak J, Bendo JA, Rybak L. The lumbar facet joint: a review of current knowledge: part 1: anatomy, biomechanics, and grading. Skeletal Radiol. 2011 Jan;40(1):13-23..

- ↑ Eubanks JD, Lee MJ, Cassinelli E, Ahn NU. Prevalence of lumbar facet arthrosis and its relationship to age, sex, and race: an anatomic study of cadaveric specimens. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007 Sep 1;32(19):2058-62.

- ↑ Binder DS, Nampiaparampil DE. The provocative lumbar facet joint. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2009;2(1):15-24.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Moon HJ, Choi KH, Kim DH, et al. Effect of lumbar stabilization and dynamic lumbar strengthening exercises in patients with chronic low back pain. Ann Rehabil Med. 2013;37(1):110-117.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cohen SP, Raja SN. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2007 Mar;106(3):591-614.

- ↑ Bob & Brad- Top 3 Signs Your Back Pain is Facet Joint Syndrome. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zqbXyreyss0

- ↑ Holder LE, Machin JL, Asdourian PL, Links JM, Sexton CC. Planar and high-resolution SPECT bone imaging in the diagnosis of facet syndrome. J Nucl Med. 1995 Jan;36(1):37-44.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Marc Safran, James E. Zachazewski,David A. Stone “Instructions for Sports Medicine Patients”, p362

- ↑ Schütz U, Cakir B, Dreinhöfer K, Richter M, Koepp H. Diagnostic value of lumbar facet joint injection: a prospective triple cross-over study. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27991.

- ↑ Christopher M. Norris. Back stability. Integrating science and therapy. Second edition. Oxford, United kingdom, 2008 (p. 15)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 MALANGA G. et al, Lumbosacral Facet Syndrome Treatment & Management., 2013

- ↑ Bronfort G, Goldsmith CH, Nelson CF, Boline PD, Anderson AV. Trunk exercise combined with spinal manipulative or NSAID therapy for chronic low back pain: a randomized, observer-blinded clinical trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996 Nov-Dec;19(9):570-82.

- ↑ Bob & Brad: Top 3 Exercises for Facet Joint Syndrome. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oIZlz7oH-ag

- ↑ Back Intelligence: Lumbar Facet Joint Pain Relief- 3 Exercises. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oIZlz7oH-ag

- ↑ Gerard Malanga, Erin Wolff. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with trigger point injections The Spine Journal, Intervention Review Article 2008. Volume 8 Issue 1 Page 243-252.