Critical Illness Polyneuropathy (CIP)

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Critical Illness Polyneuropathy (CIP) is the acute or subacute onset of extensive symmetric weakness in critical ill patients , usually with sepsis, respiratory failure, multisystem organ failure, or septic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Clinical presentation includes distal extremity weakness, wasting, and sensory loss, as well as paresthesia and decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes.[1]

Intensive Care Unit Acquired weakness (ICUAW) include 3 subsets:

- Critical Illness Polyneuropathy (CIP)

- Critical Illness Myopathy (CIM)

- Critical Illness Neuromyopathy (CINM)[2].

Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

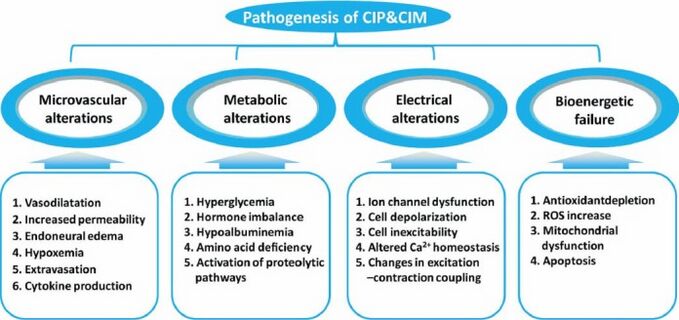

The pathophysiology for CIP remains unclear and complex, with human studies highlighting axonal degeneration [3].

It is hypothesized to be connected to:

- Drug, nutritional, metabolic, and toxic factors

- A long ICU stay

- The number of invasive procedures

- Hyperglycemia

- Decreased albumin level

- The Severity of multisystem organ failure.

With risk factors including a number of the above ie Sepsis; SIRS; Multi Organ Failure (MOF); Female Gender; Duration of Organ Dysfunction; Duration of ICU Stay; Ionotropic Support; Renal Failure; Low Serum Albumin; Hyperglycemia; Neuromuscular Blockades; Corticosteroids[4]

[4].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Visser (2006) [5] reports that the clinical features of CIP typically include:

- Muscle Weakness: Predominantly in the lower extremities. This should be suspected if there is reduced limb movement following a painful stimulus to the distal limb. Flaccid weakness can be observed symmetrically.

- Absent Facial Weakness: Cranial nerves are rarely affected.

- Muscle Wasting: Observed in one third of patients

- Reduced Muscle Reflexes: Reflexes are usually present at the start of the disease, but decrease over time.

- Difficulty in Weaning from Ventilator

- Sensory Loss: Although difficult to assess with a sedated or intubated patient.

- Impaired Consciousness: Suggested of an encephalopathy is also usually present

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Although performed rarely, the gold standard for the diagnosis of critical illness neuropathy remains electrodiagnostic testing. This includes nerve conduction studies and needle electromyography. However while EMG is the best way to of making a diagnosis of CIP, it is challenging to perform a complete study in ICU settings, including electrical interference, anasarca, hypothermia, peripheral edema, or limited patient participation in the exam. [6]

- Currently there are no validated biomarkers available.

- Although not commonly performed, CIP will demonstrate features of denervation and reinnervation with small muscle fibers, fiber-type grouping, and fiber group atrophy with widespread axonal degeneration of both motor and sensory nerves. Muscle biopsy can display thick filament loss which is commonly associated with CIM, with evidence of denervation and reinnervation changes and axonal degeneration associated with CIP[7].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Guillain-barre syndrome (GBS)

- Trauma: A spinal cord or head injury should be ruled should there be muscle weakness following a traumatic injury, as spinal shock can result in muscle weakness and areflexia [5]

- Neuromuscular blockades: Prolonged neuromuscular blockades can result in the development of acute quadriplegic myopathy, and can be identified by repetitive nerve stimulation. This can be reversed by giving cholinesterase inhibitors. Sensation and reflexes are usually spared [5]

- Critical illness myopathy (CIM): CIP and CIM usually co-exist during ICUAW[8],

Coincident illness include:

- Eaton-Lambert Syndrome: A rare autoimmune disorder characterised by muscle weakness of the limbs

- Myasthenia Gravis: A rare, long term illness that commonly affects the muscles of the eyes and eyelids, facial expressions, chewing, swallowing and speaking and other parts of the body.

- Vasculitis: Inflammation of the blood vessels.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The Oxford Muscle Grading System assists with the diagnosis of CIP. Bi-lateral testing of shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, wrist extension, hip flexion, knee extension, and dorsiflexion of the ankle will create a total score of 60[4]. 48/60 designates ICUAW or significant weakness, and an MRC score below 36/48 indicates severe weakness[9]

Management[edit | edit source]

Upon diagnosis of CIP, the interprofessional team including physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, nutritionists, social workers, and case managers need to work together to coordinate early mobilization and aggressive multifaceted rehabilitation.

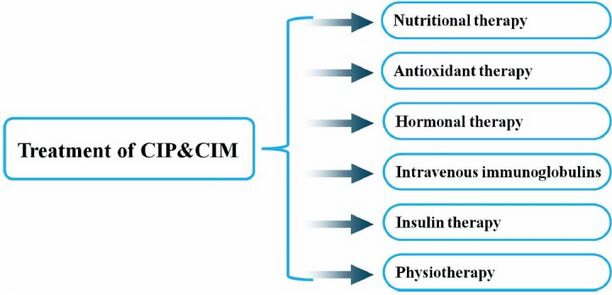

Medical management

- Glycemic Control: Studies have shown that intensive insulin therapy for hyperglycemia lowered the risk of critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy, and decreased time on ventilatory support, the duration of intensive care unit stay, and the 180-day mortality rate[3].

- Optimising Nutrition

- Treatment of Sepsis: Likely that adequate and early treatment of sepsis reduces the incidence of CIP. Treatment modalities to reduce this risk are centred around the use of semi- recumbent positioning, use of low tidal volume mechanical ventilation, and no or careful use of sedative or neuromuscular-blocking agents[5]. See Sedation in Critically-Ill Patients

- Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA), potent muscle relaxants, block neuromuscular transmission and causes paralysis of the muscle: Multiple studies have shown that there is a correlation between ICUAW and neuromuscular blockade. It is recommend that continuous vigilance is needed when NMBAs are used in critically ill patients, selecting the appropriate NMBA for each individual setting, evidence-based protocols are followed to ensure adequate sedation and analgesia, appropriate equipment for assessing the degree of neuromuscular blockade, and aggressive physical therapy regimens during periods of reduced mobility[10][5].

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Long periods of immobilisation are now being recognised as an important aspect to address when managing CIP.

Performing rehabilitation early on is a key focus in the NICE guidelines (2009 guidelines, checked December 2022, no new evidence that affects the recommendations in this guideline.)[11].

Early mobilisation facilitates and improves long-term recovery and functional independence of patients, shortening the duration of ventilation and hospitalisation[12]. Treatment should be tailored to the clinical presentation of the patient and could include:

- Passive range of movement to maintain muscle length and prevent contractures due to prolonged bed rest.

- Active/active assisted exercises to improve strength and endurance.

- Positioning in bed to facilitate improved lung function.

- Sitting on edge of bed to facilitate trunk control / balance.

- Sitting out in chair to improve lung function (either via pat slide, hoist, standing hoist or transfers).

- Mobilising to improve lung function, cardiovascular fitness, muscle strength and promote independence.

Take a deeper look by viewing this Early Mobility Assessment for Critically Ill Patients, Early Mobilization in the ICU and Implementing an Early Mobility Programme for Critically Ill Patients

Resources[edit | edit source]

NICE Guidelines (2009): Rehabilitation following Critical Illness

Guidelines for the Provision of Intensive Care Services

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Paz JC, West MP. Acute care handbook for physical therapists e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019 Oct 12. Available:https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9781455728961/acute-care-handbook-for-physical-therapists (accessed 26.12.2022)

- ↑ Appleton, R. and Kinsella, J., 2012. Intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care and Pain, 12(2), pp.62-66.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Zhou, C., Wu, L., Ni, F., Ji, W., Wu, J. and Zhang, H., 2014. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: a systematic review. Neural regeneration research, 9(1), p.101.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hermans, G. and Van den Berghe, G., 2015. Clinical review: intensive care unit acquired weakness. Critical care, 19(1), p.274.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Visser, L.H., 2006. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: clinical features, risk factors and prognosis. European journal of neurology, 13(11), pp.1203-1212.

- ↑ Plaut T, Weiss L. Electrodiagnostic Evaluation Of Critical Illness Myopathy. InStatPearls [Internet] 2021 Mar 29. StatPearls Publishing. Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562270/ (accessed 26.12.2022)

- ↑ Shepherd, S., Batra, A. and Lerner, D.P., 2017. Review of critical illness Myopathy and neuropathy. The Neurohospitalist, 7(1), pp.41-48.

- ↑ Pattanshetty, R.B. and Gaude, G.S., 2011. Critical illness myopathy and polyneuropathy-A challenge for physiotherapists in the intensive care units. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine, 15(2), p.78.

- ↑ Latronico, N. and Gosselink, R., 2015. A guided approach to diagnose severe muscle weakness in the intensive care unit. Revista Brasileira de terapia intensiva, 27(3), pp.199-201.

- ↑ Renew JR, Ratzlaff R, Hernandez-Torres V, Brull SJ, Prielipp RC. Neuromuscular blockade management in the critically Ill patient. Journal of Intensive Care. 2020 Dec;8(1):1-5.Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7245849/ (accessed 26.12.2022)

- ↑ NICE (2009). Rehabilitation after critical illness in adults. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cG83 [Accessed 26.12.2022].

- ↑ Needham, D.M., 2008. Mobilizing patients in the intensive care unit: improving neuromuscular weakness and physical function. Jama, 300(14), pp.1685-1690.