Perceptual-Motor Abilities of Infants in the 1 to 2 Month Period: Difference between revisions

m (deleted sentence on intro) |

m (A paragraph was repetead) |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- | <div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [https://members.physio-pedia.com/course_tutor/pam-versfeld/ Pam Versfeld] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | ||

== | == Infant development: 1-2 month period == | ||

This is an exciting period as it the time when infants’ perceptual-motor behaviour shifts from spontaneous movements to movements that become increasingly intentional as the infant uses longer periods of being awake and alert to explore and connect with their social and physical environment. | |||

* When awake and alert infants alternate between period of activity and periods of quiet | |||

* | * Infants gain greater control of their head posture and movements, increasing their ability for visual reach and information gathering | ||

* They look towards interesting sounds and visual events in the environment | |||

* | * They actively explore their bodies, clothing and surrounding surfaces with their hands and their feet | ||

* | * They are becoming increasingly self-aware and develop an awareness of their own bodies relative to the surrounding physical environment | ||

* | * Reaching becomes more intentional and successful. | ||

== Communication and Social | === Communication and Social Behaviour === | ||

During this period infants’ communication and social behaviour increases and become more complex, sustained and expressive.<ref>Farran LK, Yoo H, Lee CC, Bowman DD, Oller DK. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6856762/pdf/fpsyg-10-02374.pdf Temporal Coordination in Mother-Infant Vocal Interaction: A Cross-Cultural Comparison.] Front Psychol. 2019 Nov 8;10:2374.</ref> | |||

* | * First smiles occur | ||

* | * They turn their heads towards voices and other sounds in the environment | ||

* | * Quieten their limb movements or smile in response to sounds | ||

* | * Show increasing interest in faces and recognise familiar faces | ||

* | * Make eye contact | ||

* Cry differently for different needs (e.g. hungry vs tired) | |||

* Produce a range of pre-speech sounds – known as protophones - that include grunts, coos and gurgles. | |||

=== | ==== Vocalisation ==== | ||

During this period infants produce a range of pre-speech sounds, known as protophones.<ref>Oller DK, Ramsay G, Bene E, Long HL, Griebel U. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8419580/pdf/rstb.2020.0255.pdf Protophones, the precursors to speech, dominate the human infant vocal landscape.] Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2021 Oct 25;376(1836):20200255. </ref> | |||

* These sounds include grunts, squeals, coos, and vowel like sounds. | |||

* Vocalisations becomes more extended and include changes in emotional tone (known as inflexion) | |||

* Vocal behavior is often produced during social interaction but is also heard when infants are not attending to the environment. | |||

This spontaneous vocalisation allows the infant to practice and explore different ways of producing a range of different sounds which provides the foundation for later babbling and words. <ref>Long HL, Bowman DD, Yoo H, Burkhardt-Reed MM, Bene ER, Oller DK. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7406057/pdf/pone.0224956.pdf Social and endogenous infant vocalizations.] PLoS One. 2020 Aug 5;15(8):e0224956.</ref> | |||

==== Social interaction and mirroring ==== | |||

In the 1-2 month period infants continue to pay special attention to faces. They also start to recognise familiar faces and will smile at them. Their ability to sustain social interaction increases and they are figuring out the process of turn taking which is an inherent aspect of a conversation. Adult social partners will often imitate infants’ facial expressions, lip and jaw movements and vocalisations which act as a mirror that allows the infant to “see” and “hear” copies of their own actions. | |||

When speaking to infants, adults typically alter the acoustic properties of their speech in a variety of ways compared with how they speak to other adults; for example, they use higher pitch, increased pitch range that is making the voice go up and down in tone, more pitch variability, and slower speech rate. Recent research by Tanya Broesch and Gregory Bryant has shown that these vocal changes happen similarly, not only across industrialised populations but also in traditional societies.<ref>Broesch TL, Bryant GA. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271671965_Prosody_in_Infant-Directed_Speech_Is_Similar_Across_Western_and_Traditional_Cultures Prosody in infant-directed speech is similar across western and traditional cultures.] Journal of Cognition and Development. 2015 Jan 1;16(1):31-43.</ref> | |||

==== | ==== Spontaneous touches ==== | ||

During this period infants continue to use their hands to gather information about the surfaces they encounter. Contact with a surface is often associated with exploratory movements of the hand across the surface, or repeated flexion and extension of the fingers and grasping. Independent movements of the fingers are also frequently seen, especially when the infant is socially engaged or is paying attention to an object within reaching distance. <ref>DiMercurio A, Connell JP, Clark M, Corbetta D. [https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02613/full A naturalistic observation of spontaneous touches to the body and environment in the first 2 months of life.] Frontiers in psychology. 2018 Dec 18;9:2613.</ref> | |||

=== Perceptual-Motor Development<ref>Baek S, Jaffe-Dax S, Emberson LL. How an infant's active response to structured experience supports perceptual-cognitive development. Prog Brain Res. 2020;254:167-186.</ref> === | |||

* During the 1-2 month period the infant is awake and alert for longer periods of time, increasingly responds to sounds and sights from the environment and gains more control of movements of the head and limbs | |||

* Head control in supine is improving as the infant learns to hold the head steady in the midline as well as turn the head to locate interesting sights and sounds. | |||

* When held upright infants can keep the head erect for extended periods of time. | |||

* Neck rotation is still associated with extension and lateral flexion. | |||

* Spontaneous movements of the lower extremities, along with the pull of gravity serve to stretch the hip and knee flexor muscles, leading to increased range of extension of the extremity joints. | |||

* Postural control of the trunk in supine is improving but movement of the extremities still leads to lateral displacement and sometimes rotation of the pelvis. | |||

* Vigorous kicking of the lower extremities (LEs) is often associated with abduction of the shoulders and extension of the elbows as the infant works to maintain a steady torso. | |||

* Kicking movements still show strong coupling between the hip and knee joints, however the ability to uncouple hip and knee emerges when the infant engages in goal directed actions of the foot, such as reaching to a target with the foot. | |||

* Whole body general movements give way to fidgety general movements from around 9 weeks. | |||

* Infants start to reach successfully towards interesting objects within reach and start to use finger movements to explore objects. | |||

* Infants actively explore surfaces with their feet and hands. | |||

* Although simultaneous flexion and extension movements of the fingers are still common, independent movements of the fingers become more prominent. | |||

==== General and fidgety movements ==== | |||

General movements continue to be characterised by writhing movements that involve the head, trunk and extremities in the 1-2 month period. Writhing general movements in the healthy full term infant are described as complex and involve the entire body, notably arm, leg, neck, and trunk movements in variable sequence. They wax and they wane varying in intensity and speed, range of motion, and have a gradual onset and a gradual end. However, towards the end of this period fidgety movements (FMs) are increasingly present. <ref name=":0">Einspieler C, Marschik PB, Prechtl HF. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247399672_Human_Motor_Behavior_Prenatal_Origin_and_Early_Postnatal_Development Human motor behavior: Prenatal origin and early postnatal development.] Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2008;216(3):147.</ref> | |||

FMs are small movements of moderate speed with variable acceleration of the neck, trunk, and limbs in all directions. They may appear as early as six weeks after term, but usually occur from around 9 weeks until 16–20 weeks, occasionally even a few weeks longer. They fade out when antigravity and intentional movements start to dominate. | |||

=== | The presence and character of fidgety movements are good indicators of the integrity of the infant's nervous system.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

==='''Head control and neck movements'''=== | |||

At the beginning of the 1-2 month period the infant still tends to lie supine with the head turned to one or the other side. Head rotation continues to be associated with some neck extension and lateral rotation. Head turning may be associated with an asymmetrical tonic neck reflex (ATNR) posture, but this is not obligatory. | |||

[[File:Pamv9.png|center|thumb|400x400px]] | |||

By the end of the 1-2 month period the infant is more inclined to hold the head in the midline and easily turns the head to look at interesting objects and events in the environment. | |||

[[File:Pamv2.png|thumb|233x233px|alt=|center]] | |||

At this age infants tend to lie with the upper extremities (UEs) abducted and extended, a position that helps to stabilize the trunk and provide a stable base for head movements and kicking.<ref name=":1">Bly L. [https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Motor-Skills-Acquisition-in-the-First-Year%3A-An-to-Bly/73bd3e94f6dd83e707be95704e920bd9304fa6bb Motor skills acquisition in the first year: An illustrated guide to normal development]. Psychological Corporation; 1994.</ref> | |||

[[File:Pamv3.png|thumb|214x214px|alt=|center]] | |||

The infant is also able to combine neck rotation with extension of the head to look upwards. | |||

However, control of the exact position of the head is clearly still developing, as rotation is usually associated with some neck extension and lateral flexion. This combination of movements suggests that the movement is brought about by contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscles, with limited action in the deep neck stabilisers.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

[[File:Pamv4.png|thumb|229x229px|alt=|center]] | |||

The 1-2 month old infant is able to visually follow an object from the side to the midline, as well as follow an object moved in a downwards direction. The ability to follow an object across the midline is not present | |||

[[File:Pamv5.png|thumb|500x500px|alt=|center]] | |||

=== Upper extremity (UE) actions === | |||

== | During periods of relative quiet the one-month-old infant adopts a variety of postures of the upper extremities. Abduction of the shoulders with the upper arms resting on the support surface is often observed – in this position the UEs serve as outriggers and help to stabilize the trunk when moving the head and lower extremities. Interestingly this co-opting of the UEs for a postural function during this period is associated with a decrease in the occurrence of swiping actions towards objects within reach.<ref name=":2">von Hofsten C. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232516582_Hofsten_C_Developmental_changes_in_the_organization_of_prereaching_movements_Developmental_Psychology_203_378-388 Developmental changes in the organization of prereaching movements]. Developmental psychology. 1984 May;20(3):378.</ref> | ||

Head rotation may be associated with the fencing position (with extension of the elbow on the side to which the face is turned). However this association decreases over the 1-2 month period, and importantly, is never obligatory. | |||

The tendency to abduct the shoulders and use the UEs as outriggers decreases towards the end of this period when infants start to bring their hands into the midline. | |||

[[File:Pamv6.png|center|thumb|500x500px]] | |||

At the beginning of the 1-2 month period infants produce large range swiping movements of the upper extremities. These swiping movements are associated with elbow extension and extension of the fingers. The hand comes close to the object, but mostly does not make contact. | |||

[[File:Pamv7.png|center|thumb|500x500px]] | |||

Over the coming weeks the infant gains more control over reaching movements and starts to reach towards objects within easy reach with greater success. The extension of the fingers seen in the one month old infant become less pronounced<ref name=":2" /> | |||

The infant brings the hand into the proximity of the toy and then uses small range movements of the shoulder and elbow to explore different ways of touching and grasping the toy. | |||

Towards the end of this period (10-12 weeks), as the infant's ability to steady the head and trunk when moving the UEs becomes more reliable the infant gains more control of reaching towards toys. | |||

They are able to bring the hand into contact with the toy and start to use the fingers to explore it. | |||

This is the start of the ability to stabilise the position of the hand in space and at the same time use independent finger movements to gather information about the texture, structure and behaviour of objects. Visual attention to the toy and the hand provides further information that starts to link what is felt and seen. | |||

[[File:Pamv8.png|thumb|400x400px|alt=|center]] | |||

=== Exploratory hand movements === | |||

During this period infants continue to use their hands to gather information about the surfaces they encounter. Contact with a surface is often associated with exploratory movements of the hand across the surface, or repeated flexion and extension of the fingers. | |||

Independent movements of the fingers are also frequently seen, especially when the infant is socially engaged or is paying attention to an object within reaching distance. | |||

=== Postural sway and postural stability === | |||

Observing an infant during periods of quiet supine lying allows one to observe the postural sway present in the trunk. These exploratory movements allow the postural system to gather the sensory information needed for estimating the position of the body as a whole and exploring the most effective strategies to maintain a stable posture.<ref>Dusing SC, Thacker LR, Stergiou N, Galloway JC. Early complexity supports development of motor behaviors in the first months of life. Developmental Psychobiology. 2013;55(4):404-14.</ref> | |||

Here you see Will lying quietly at 5 and 10 weeks of age. The upper arms come to rest on the support surface and the continuous lateral sway of the trunk provides changing contact between the upper arm and the support surface. | |||

Will is also exploring the contact between his feet and the support surface, and between each other. This exploration is important for developing the infant's ability to use surfaces to support their actions. | |||

[[File:Pamv9.png|thumb|alt=|center]] | |||

=== Lower extremity (LE) movements === | |||

The 1-2 month old infant engages in periods of relative calm when the feet rest on the support surface with varying amounts of flexion of the hips and knees. | |||

At 7 weeks Will's range of hip and knee extension is still restricted by the remaining physiological flexor stiffness. | |||

[[File:Pamv10.png|center|thumb|500x500px]] | |||

By 10 weeks Will has close to full range of hip and knee extension. Full hip extension is associated with anterior pelvic tilt. | |||

The range of ankle plantar flexion has also increased. | |||

[[File:Pamv11.png|thumb|225x225px|alt=|center]] | |||

The 1-2 month old still engages in extended periods of kicking. Movement patterns include repeated single leg kicking with alternate leg kicking and bilateral hip and knee flexion and extension. | |||

At this age hip and knee movements are still coupled. The ankles remain in dorsiflexion with intermittent flexion and extension of the toes. | |||

[[File:Pamv12.png|thumb|400x400px|alt=|center]] | |||

The range of movement of hip flexion and knee extension during kicking movements increases over the 1-2 month period, as seen in these pictures of Will at 10 weeks. | |||

=== Lower Extremity Bridging === | |||

From time to time one or both feet push down on the SS. Pushing down with one foot is associated with head and trunk extension and lateral weight shift. | |||

[[File:Pamv13.png|thumb|400x400px|alt=|center]] | |||

=== Foot reaching === | |||

Although spontaneous kicking actions tend to still show strong intra-limb coupling, research has shown that 2 month old infants can adapt their LE actions to operate a mobile and make contact with a toy that has been suspended in the midline. | |||

=== Pull-to-sit === | |||

The infant's response to the pull-to-sit manoeuvre is often used as a test when assessing motor development. It provides a good measure of the infant's neck muscle strength as well as the development of effective anticipatory postural responses. | |||

By the end of the 1-2 month period, infants have learned to anticipate being lifted and will participate in the PTS manoeuvre by engaging the neck and trunk flexor muscles, stiffening the UEs and flexing the hips. | |||

The head is held in line with the trunk as the shoulders are lifted. | |||

[[File:Pamv14.png|center|thumb|700x700px]] | |||

Once in the upright position the head is held erect, and the infant is able to lift the face to look at the person who has pulled him into sitting. | |||

[[File:Pamv15.png|thumb|400x400px|alt=|center]] | |||

=== Sitting === | === Sitting === | ||

[[File: | Bly (1994)<ref name=":1" /> describes the characteristics of sitting at the beginning of the 1-2 month period as follows: | ||

* In supported sitting the head falls forwards although the infant does make brief attempts to hold it up. | |||

* The infant's UEs no longer hang loosely at the infant's side. | |||

* During brief periods of lifting the head there is retraction of the scapulae, increased flexion of the elbows, forearm pronation, extension of the wrist and flexion of the finger. | |||

* Bly surmises that the retraction of the scapulae may provide synergistic stability for head lifting. | |||

* The hips are flexed, abducted and laterally rotated, the knees more flexed than in the neonatal period, and the ankles are strongly dorsiflexed and everted as in the neonatal period. | |||

Over the 1-2 month period the infants gain increasing control of the position of the trunk when they sit with support around the hips. | |||

They are able to maintain the trunk in a semi-erect position, with the line of gravity falling anterior the flexion-extension axis of the hips, creating a gravity flexion moment at the hips which is counteracted by the hips extensors. The trunk and neck extensors work to maintain some extension in the trunk. | |||

[[File:Pamv16.png|thumb|400x400px|alt=|center]] | |||

The ability to control the position of the trunk is less well developed when the trunk is tilted backwards so that the LOG falls posterior to the flexion/extension axis of the hips, | |||

Notice how this rapid backwards movement initiates a response in the trunk and neck flexors, as well as reactions in his upper limbs as the postural system responds to the rapid backwards movement of the head. | |||

[[File:Pamv17.png|thumb|450x450px|alt=|center]] | |||

=== Response to being picked up and moved === | |||

By the end of the 1-2 month period infants have started to anticipate being picked up and moved. | |||

They are able to hold the head in line with the trunk when supported around the chest, especially when tipped forwards or laterally. | |||

[[File:Pamv18.png|thumb|450x450px|alt=|center]] | |||

=== Prone <ref>Hewitt L, Kerr E, Stanley RM, Okely AD. [https://watermark.silverchair.com/peds_20192168.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAqAwggKcBgkqhkiG9w0BBwagggKNMIICiQIBADCCAoIGCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQMwq4dtML7QW324ERfAgEQgIICU78NJsc4-J-iLB218tvV3kg-x65PS-k5XM5WiPj48-OKz5KXKNjAE3Tix8LzG6q5tOtgbJyT8u9-_4yVdYeD2f-TUVuGisqSp4DCUg7s1TnCXgcxjey3yGHyHwNwTAXXi3GrjGDxiBPpcrmyfVEMadupjw5DoJdknOmoOdXzAPDNtUxTzYl-rneTD1lcf95PKRYEsIcbl0HfhtrD-g_bCNjyxDJvj_NkSeQInpwWFuVlrshC3-o95b09gucq-dnRtlPQW3wlLbx2jCjN0bWihg61AlD1K6W3_P2rblEpb2f3XgOFEhjjGTG5ZBevdh4N0aZbKlp9ojOzXav2ua45ZhOBl_lSt47JuUCN5ODZnpiIcfvdhMr1bC7yjQlY7K9KcWKhQgHK_GbXITne-oM2LHX8EBIXBj6FidROWYYS-Z-_HFdL9MtFSjyz9QohIacT5qnBs0KsNWieivU8bE0OF5fufFIfPuEz9g6ZBJWr4KP4YEjp4B6zpVQeMmp1_uYvYwifI1NkTpj1-3N3TWN1EcbRh8_0IVz4yeRyj_CKVtm2n1A6oR5qSmybFpOd1vMCzc8fvXDuIGF8nqGal9bgpPkpsOhDuISDPBU4uRfIxQ7L9GS1PsajPLjsZzOOmBcfyYhXUPL-PsFICEfyfgievSuvf5zsM9ZsoTZBgccXENgdpKsJIrXBikiKCE8oxemspnhDaxNCIx1l6MQ3okFWcbcF9V5XSL-X2DCnKXAlwZkggMuSuZMGaidrozPug-vXgsrMgFZLaNDiDqYeM9XeYK5_PV8 Tummy Time and Infant Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review.] Pediatrics. 2020 Jun;145(6):e20192168. </ref> === | |||

'''Back to sleep advice'''. In the past many infants were put into prone for sleeping, but more recently because prone sleeping is a risk factor for sudden infant death, parents are advised to let infants sleep on their backs. As a result many infants do not like being placed in prone, quickly start to cry and also quickly learn to roll from prone to supine. | |||

At the beginning of the 1-2 month period, infants start to lift the head up off the support surface (SS) for brief periods of time. This is accomplished by the neck and thoracic extensor muscle activity. | |||

[[File:Pamv19.png|thumb|alt=|center]] | |||

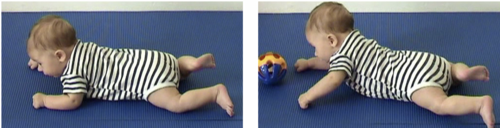

When in prone infants engage in active kicking, alternating between unilateral and bilateral hip and knee flexion and extension. The ankles remain dorsiflexed, with the range of dorsiflexion (DF) increasing with full hip and knee flexion and decreasing with hip and knee extension. | |||

Unilateral kicking movements are associated with lateral flexion of the trunk with a lateral shift in weight bearing. Bilateral hip and knee flexion is associated with anterior pelvic tilt and a cephalad shift of weight onto the upper torso. | |||

[[File:Pamv20.png|thumb|500x500px|alt=|center]] | |||

=== Rolling from prone to supine === | |||

Will's ability to initiate rolling from prone to supine illustrate how by 5 weeks he has learned to exploit his rapidly developing control of movement of the extremities to initiate a sequence of movements directed towards achieving a goal. | |||

After a period of kicking, Will decides that he has had enough of being in prone, and initiates rolling to supine by lifting his head and extending the thoracic spine. These movements are associated with a more extended position of the hips and knees bilaterally and a shift of his centre of mass (COM) caudally. | |||

He rotates his shoulder girdle back on the right, flexes the right hip "falls" onto his back. | |||

[[File:Pamv21.png|center|thumb|800x800px]] | |||

I turn Will back into prone, and he immediately rolls back into supine, this time using a slightly different pattern of movement. He pushes down on his right hand, extends his elbow, and extends the thoracic spine. The COM shifts caudally, but there is no associated extension of the hips. Will collapses onto his left side with the hips still in flexion, and then rolls onto his back. | |||

[[File:Pamv22.png|center|thumb|800x800px]] | |||

By the end of the 1-2 month period, the infant's ability to lift the head and extend the thoracic spine has improved. This is associated with taking some weight on the hands. | |||

Extension of the neck and thoracic spine is now associated with extension and adduction of the hips. | |||

The ROM of extension at the hips and knees has increased. Some of the time flexion of the knee is associated with flexion of the hip, but not always. This is the beginning of uncoupling of movements the hip and knee flexion and the beginning of the ability to dissociate movements of the two joints. | |||

[[File:Pamv23.png|thumb|500x500px|alt=|center]] | |||

== Resources == | == Resources == | ||

| Line 132: | Line 224: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Rehabilitation]] | [[Category:Rehabilitation]] | ||

[[Category:ReLAB | [[Category:ReLAB-HS Course Page]] | ||

[[Category:Paediatrics]] | [[Category:Paediatrics]] | ||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

Latest revision as of 07:36, 25 September 2023

Infant development: 1-2 month period[edit | edit source]

This is an exciting period as it the time when infants’ perceptual-motor behaviour shifts from spontaneous movements to movements that become increasingly intentional as the infant uses longer periods of being awake and alert to explore and connect with their social and physical environment.

- When awake and alert infants alternate between period of activity and periods of quiet

- Infants gain greater control of their head posture and movements, increasing their ability for visual reach and information gathering

- They look towards interesting sounds and visual events in the environment

- They actively explore their bodies, clothing and surrounding surfaces with their hands and their feet

- They are becoming increasingly self-aware and develop an awareness of their own bodies relative to the surrounding physical environment

- Reaching becomes more intentional and successful.

Communication and Social Behaviour[edit | edit source]

During this period infants’ communication and social behaviour increases and become more complex, sustained and expressive.[1]

- First smiles occur

- They turn their heads towards voices and other sounds in the environment

- Quieten their limb movements or smile in response to sounds

- Show increasing interest in faces and recognise familiar faces

- Make eye contact

- Cry differently for different needs (e.g. hungry vs tired)

- Produce a range of pre-speech sounds – known as protophones - that include grunts, coos and gurgles.

Vocalisation[edit | edit source]

During this period infants produce a range of pre-speech sounds, known as protophones.[2]

- These sounds include grunts, squeals, coos, and vowel like sounds.

- Vocalisations becomes more extended and include changes in emotional tone (known as inflexion)

- Vocal behavior is often produced during social interaction but is also heard when infants are not attending to the environment.

This spontaneous vocalisation allows the infant to practice and explore different ways of producing a range of different sounds which provides the foundation for later babbling and words. [3]

Social interaction and mirroring[edit | edit source]

In the 1-2 month period infants continue to pay special attention to faces. They also start to recognise familiar faces and will smile at them. Their ability to sustain social interaction increases and they are figuring out the process of turn taking which is an inherent aspect of a conversation. Adult social partners will often imitate infants’ facial expressions, lip and jaw movements and vocalisations which act as a mirror that allows the infant to “see” and “hear” copies of their own actions.

When speaking to infants, adults typically alter the acoustic properties of their speech in a variety of ways compared with how they speak to other adults; for example, they use higher pitch, increased pitch range that is making the voice go up and down in tone, more pitch variability, and slower speech rate. Recent research by Tanya Broesch and Gregory Bryant has shown that these vocal changes happen similarly, not only across industrialised populations but also in traditional societies.[4]

Spontaneous touches[edit | edit source]

During this period infants continue to use their hands to gather information about the surfaces they encounter. Contact with a surface is often associated with exploratory movements of the hand across the surface, or repeated flexion and extension of the fingers and grasping. Independent movements of the fingers are also frequently seen, especially when the infant is socially engaged or is paying attention to an object within reaching distance. [5]

Perceptual-Motor Development[6][edit | edit source]

- During the 1-2 month period the infant is awake and alert for longer periods of time, increasingly responds to sounds and sights from the environment and gains more control of movements of the head and limbs

- Head control in supine is improving as the infant learns to hold the head steady in the midline as well as turn the head to locate interesting sights and sounds.

- When held upright infants can keep the head erect for extended periods of time.

- Neck rotation is still associated with extension and lateral flexion.

- Spontaneous movements of the lower extremities, along with the pull of gravity serve to stretch the hip and knee flexor muscles, leading to increased range of extension of the extremity joints.

- Postural control of the trunk in supine is improving but movement of the extremities still leads to lateral displacement and sometimes rotation of the pelvis.

- Vigorous kicking of the lower extremities (LEs) is often associated with abduction of the shoulders and extension of the elbows as the infant works to maintain a steady torso.

- Kicking movements still show strong coupling between the hip and knee joints, however the ability to uncouple hip and knee emerges when the infant engages in goal directed actions of the foot, such as reaching to a target with the foot.

- Whole body general movements give way to fidgety general movements from around 9 weeks.

- Infants start to reach successfully towards interesting objects within reach and start to use finger movements to explore objects.

- Infants actively explore surfaces with their feet and hands.

- Although simultaneous flexion and extension movements of the fingers are still common, independent movements of the fingers become more prominent.

General and fidgety movements[edit | edit source]

General movements continue to be characterised by writhing movements that involve the head, trunk and extremities in the 1-2 month period. Writhing general movements in the healthy full term infant are described as complex and involve the entire body, notably arm, leg, neck, and trunk movements in variable sequence. They wax and they wane varying in intensity and speed, range of motion, and have a gradual onset and a gradual end. However, towards the end of this period fidgety movements (FMs) are increasingly present. [7]

FMs are small movements of moderate speed with variable acceleration of the neck, trunk, and limbs in all directions. They may appear as early as six weeks after term, but usually occur from around 9 weeks until 16–20 weeks, occasionally even a few weeks longer. They fade out when antigravity and intentional movements start to dominate.

The presence and character of fidgety movements are good indicators of the integrity of the infant's nervous system.[7]

Head control and neck movements[edit | edit source]

At the beginning of the 1-2 month period the infant still tends to lie supine with the head turned to one or the other side. Head rotation continues to be associated with some neck extension and lateral rotation. Head turning may be associated with an asymmetrical tonic neck reflex (ATNR) posture, but this is not obligatory.

By the end of the 1-2 month period the infant is more inclined to hold the head in the midline and easily turns the head to look at interesting objects and events in the environment.

At this age infants tend to lie with the upper extremities (UEs) abducted and extended, a position that helps to stabilize the trunk and provide a stable base for head movements and kicking.[8]

The infant is also able to combine neck rotation with extension of the head to look upwards.

However, control of the exact position of the head is clearly still developing, as rotation is usually associated with some neck extension and lateral flexion. This combination of movements suggests that the movement is brought about by contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscles, with limited action in the deep neck stabilisers.[8]

The 1-2 month old infant is able to visually follow an object from the side to the midline, as well as follow an object moved in a downwards direction. The ability to follow an object across the midline is not present

Upper extremity (UE) actions[edit | edit source]

During periods of relative quiet the one-month-old infant adopts a variety of postures of the upper extremities. Abduction of the shoulders with the upper arms resting on the support surface is often observed – in this position the UEs serve as outriggers and help to stabilize the trunk when moving the head and lower extremities. Interestingly this co-opting of the UEs for a postural function during this period is associated with a decrease in the occurrence of swiping actions towards objects within reach.[9]

Head rotation may be associated with the fencing position (with extension of the elbow on the side to which the face is turned). However this association decreases over the 1-2 month period, and importantly, is never obligatory.

The tendency to abduct the shoulders and use the UEs as outriggers decreases towards the end of this period when infants start to bring their hands into the midline.

At the beginning of the 1-2 month period infants produce large range swiping movements of the upper extremities. These swiping movements are associated with elbow extension and extension of the fingers. The hand comes close to the object, but mostly does not make contact.

Over the coming weeks the infant gains more control over reaching movements and starts to reach towards objects within easy reach with greater success. The extension of the fingers seen in the one month old infant become less pronounced[9]

The infant brings the hand into the proximity of the toy and then uses small range movements of the shoulder and elbow to explore different ways of touching and grasping the toy.

Towards the end of this period (10-12 weeks), as the infant's ability to steady the head and trunk when moving the UEs becomes more reliable the infant gains more control of reaching towards toys.

They are able to bring the hand into contact with the toy and start to use the fingers to explore it.

This is the start of the ability to stabilise the position of the hand in space and at the same time use independent finger movements to gather information about the texture, structure and behaviour of objects. Visual attention to the toy and the hand provides further information that starts to link what is felt and seen.

Exploratory hand movements[edit | edit source]

During this period infants continue to use their hands to gather information about the surfaces they encounter. Contact with a surface is often associated with exploratory movements of the hand across the surface, or repeated flexion and extension of the fingers.

Independent movements of the fingers are also frequently seen, especially when the infant is socially engaged or is paying attention to an object within reaching distance.

Postural sway and postural stability[edit | edit source]

Observing an infant during periods of quiet supine lying allows one to observe the postural sway present in the trunk. These exploratory movements allow the postural system to gather the sensory information needed for estimating the position of the body as a whole and exploring the most effective strategies to maintain a stable posture.[10]

Here you see Will lying quietly at 5 and 10 weeks of age. The upper arms come to rest on the support surface and the continuous lateral sway of the trunk provides changing contact between the upper arm and the support surface.

Will is also exploring the contact between his feet and the support surface, and between each other. This exploration is important for developing the infant's ability to use surfaces to support their actions.

Lower extremity (LE) movements[edit | edit source]

The 1-2 month old infant engages in periods of relative calm when the feet rest on the support surface with varying amounts of flexion of the hips and knees.

At 7 weeks Will's range of hip and knee extension is still restricted by the remaining physiological flexor stiffness.

By 10 weeks Will has close to full range of hip and knee extension. Full hip extension is associated with anterior pelvic tilt.

The range of ankle plantar flexion has also increased.

The 1-2 month old still engages in extended periods of kicking. Movement patterns include repeated single leg kicking with alternate leg kicking and bilateral hip and knee flexion and extension.

At this age hip and knee movements are still coupled. The ankles remain in dorsiflexion with intermittent flexion and extension of the toes.

The range of movement of hip flexion and knee extension during kicking movements increases over the 1-2 month period, as seen in these pictures of Will at 10 weeks.

Lower Extremity Bridging[edit | edit source]

From time to time one or both feet push down on the SS. Pushing down with one foot is associated with head and trunk extension and lateral weight shift.

Foot reaching[edit | edit source]

Although spontaneous kicking actions tend to still show strong intra-limb coupling, research has shown that 2 month old infants can adapt their LE actions to operate a mobile and make contact with a toy that has been suspended in the midline.

Pull-to-sit[edit | edit source]

The infant's response to the pull-to-sit manoeuvre is often used as a test when assessing motor development. It provides a good measure of the infant's neck muscle strength as well as the development of effective anticipatory postural responses.

By the end of the 1-2 month period, infants have learned to anticipate being lifted and will participate in the PTS manoeuvre by engaging the neck and trunk flexor muscles, stiffening the UEs and flexing the hips.

The head is held in line with the trunk as the shoulders are lifted.

Once in the upright position the head is held erect, and the infant is able to lift the face to look at the person who has pulled him into sitting.

Sitting[edit | edit source]

Bly (1994)[8] describes the characteristics of sitting at the beginning of the 1-2 month period as follows:

- In supported sitting the head falls forwards although the infant does make brief attempts to hold it up.

- The infant's UEs no longer hang loosely at the infant's side.

- During brief periods of lifting the head there is retraction of the scapulae, increased flexion of the elbows, forearm pronation, extension of the wrist and flexion of the finger.

- Bly surmises that the retraction of the scapulae may provide synergistic stability for head lifting.

- The hips are flexed, abducted and laterally rotated, the knees more flexed than in the neonatal period, and the ankles are strongly dorsiflexed and everted as in the neonatal period.

Over the 1-2 month period the infants gain increasing control of the position of the trunk when they sit with support around the hips.

They are able to maintain the trunk in a semi-erect position, with the line of gravity falling anterior the flexion-extension axis of the hips, creating a gravity flexion moment at the hips which is counteracted by the hips extensors. The trunk and neck extensors work to maintain some extension in the trunk.

The ability to control the position of the trunk is less well developed when the trunk is tilted backwards so that the LOG falls posterior to the flexion/extension axis of the hips,

Notice how this rapid backwards movement initiates a response in the trunk and neck flexors, as well as reactions in his upper limbs as the postural system responds to the rapid backwards movement of the head.

Response to being picked up and moved[edit | edit source]

By the end of the 1-2 month period infants have started to anticipate being picked up and moved.

They are able to hold the head in line with the trunk when supported around the chest, especially when tipped forwards or laterally.

Prone [11][edit | edit source]

Back to sleep advice. In the past many infants were put into prone for sleeping, but more recently because prone sleeping is a risk factor for sudden infant death, parents are advised to let infants sleep on their backs. As a result many infants do not like being placed in prone, quickly start to cry and also quickly learn to roll from prone to supine.

At the beginning of the 1-2 month period, infants start to lift the head up off the support surface (SS) for brief periods of time. This is accomplished by the neck and thoracic extensor muscle activity.

When in prone infants engage in active kicking, alternating between unilateral and bilateral hip and knee flexion and extension. The ankles remain dorsiflexed, with the range of dorsiflexion (DF) increasing with full hip and knee flexion and decreasing with hip and knee extension.

Unilateral kicking movements are associated with lateral flexion of the trunk with a lateral shift in weight bearing. Bilateral hip and knee flexion is associated with anterior pelvic tilt and a cephalad shift of weight onto the upper torso.

Rolling from prone to supine[edit | edit source]

Will's ability to initiate rolling from prone to supine illustrate how by 5 weeks he has learned to exploit his rapidly developing control of movement of the extremities to initiate a sequence of movements directed towards achieving a goal.

After a period of kicking, Will decides that he has had enough of being in prone, and initiates rolling to supine by lifting his head and extending the thoracic spine. These movements are associated with a more extended position of the hips and knees bilaterally and a shift of his centre of mass (COM) caudally.

He rotates his shoulder girdle back on the right, flexes the right hip "falls" onto his back.

I turn Will back into prone, and he immediately rolls back into supine, this time using a slightly different pattern of movement. He pushes down on his right hand, extends his elbow, and extends the thoracic spine. The COM shifts caudally, but there is no associated extension of the hips. Will collapses onto his left side with the hips still in flexion, and then rolls onto his back.

By the end of the 1-2 month period, the infant's ability to lift the head and extend the thoracic spine has improved. This is associated with taking some weight on the hands.

Extension of the neck and thoracic spine is now associated with extension and adduction of the hips.

The ROM of extension at the hips and knees has increased. Some of the time flexion of the knee is associated with flexion of the hip, but not always. This is the beginning of uncoupling of movements the hip and knee flexion and the beginning of the ability to dissociate movements of the two joints.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Understanding Newborn Behaviour

- Newborn Perceptual Motor Behaviour

- Development Skills Training for the 1-2 month old

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Farran LK, Yoo H, Lee CC, Bowman DD, Oller DK. Temporal Coordination in Mother-Infant Vocal Interaction: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Front Psychol. 2019 Nov 8;10:2374.

- ↑ Oller DK, Ramsay G, Bene E, Long HL, Griebel U. Protophones, the precursors to speech, dominate the human infant vocal landscape. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2021 Oct 25;376(1836):20200255.

- ↑ Long HL, Bowman DD, Yoo H, Burkhardt-Reed MM, Bene ER, Oller DK. Social and endogenous infant vocalizations. PLoS One. 2020 Aug 5;15(8):e0224956.

- ↑ Broesch TL, Bryant GA. Prosody in infant-directed speech is similar across western and traditional cultures. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2015 Jan 1;16(1):31-43.

- ↑ DiMercurio A, Connell JP, Clark M, Corbetta D. A naturalistic observation of spontaneous touches to the body and environment in the first 2 months of life. Frontiers in psychology. 2018 Dec 18;9:2613.

- ↑ Baek S, Jaffe-Dax S, Emberson LL. How an infant's active response to structured experience supports perceptual-cognitive development. Prog Brain Res. 2020;254:167-186.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Einspieler C, Marschik PB, Prechtl HF. Human motor behavior: Prenatal origin and early postnatal development. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2008;216(3):147.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bly L. Motor skills acquisition in the first year: An illustrated guide to normal development. Psychological Corporation; 1994.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 von Hofsten C. Developmental changes in the organization of prereaching movements. Developmental psychology. 1984 May;20(3):378.

- ↑ Dusing SC, Thacker LR, Stergiou N, Galloway JC. Early complexity supports development of motor behaviors in the first months of life. Developmental Psychobiology. 2013;55(4):404-14.

- ↑ Hewitt L, Kerr E, Stanley RM, Okely AD. Tummy Time and Infant Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun;145(6):e20192168.