Newborn Perceptual Motor Behaviour

Original Editor - Robin Tacchetti based on the course by Pam Versfeld

Top Contributors - Robin Tacchetti, Robin Leigh Tacchetti, Tarina van der Stockt, Ewa Jaraczewska, Kim Jackson and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

When newborn infants (0-4 weeks old) are awake and alert and lying on a firm surface they respond to visual and auditory events in the environment and actively engage in spontaneous movements of the limbs. The looking, listening and moving provides opportunities for linking what they do to what is seen, heard and felt, creating the perception-action loops that are the basis for making the shift from spontaneous exploratory movements to intentional, goal directed actions that allow the infant to interact with people, things and events in their environment.[1]

Limb Movement Synergies at Birth[edit | edit source]

The multi-segmented structure of the body provides the basis for producing the varied movement patterns seen in human actions. To simplify control of the many degrees of freedom inherent in a multi-segmented body, spontaneous infant movements are constrained and organised into synergies.[2]

- Lower limb synergy pattern includes intralimb coupling of

- hip flexion, knee flexion and dorsiflexion

- hip extension and knee extension

- Upper limb synergy pattern includes a combination of

- shoulder and elbow extension with extension of the fingers and wrist;

- flexion of the elbow with finger flexion.[3]

These whole body movements, called general movements or GMs, are complex and involve the entire body, notably arm, leg, neck, and trunk movements in variable sequences.[3]

Over the first few months as the infant explores different ways of interacting with the environment and as the frontal motor areas become more active, the strong intralimb coupling lessens as movement are adapted to allow for effective interaction with the environment. [1]

Head Posture[edit | edit source]

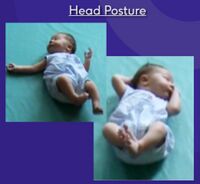

- In supine the newborn's head is mostly rotated to one side, often with a preference for a particular side, usually to the right.[4] The reason for this tendency is unclear.

- A prominent feature of head rotation in the first two months is the tendency for rotation to be coupled with neck extension and lateral flexion to the opposite side, which is a reflection of the balance in activity between the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles and deep neck flexor muscle activity.[5]

- Over the first few weeks the infant learns to turn the head to the midline, and can sustain the position briefly, especially when supported by visual attention to an interesting person, object or event.[1]

- Typically the head is held in the mid-position for brief periods of time when the infant is actively moving the limbs or is distressed.[6]

- Over the next few weeks the infant will develop the the bilateral antigravity neck muscle strength and control needed to counteract the force of gravity (which creates a turning moment acting on the Center of Gravity (COG) of the head) and maintain the head in the midline for longer periods of time.

Newborn Rolling[edit | edit source]

In neonates with typical/normal limb stiffness (muscle tone), head turning may initiate partial rolling to the side. This response may be due to the neonatal neck righting reflex[5] but may also be because turning of the neck shifts the infants weight laterally which destabilises the trunk and the infant "'topples" over to side lying.

Visual Attention[edit | edit source]

- From the first weeks infants pay attention to interesting objects that come into their field of vision. Visual attention is usually associated with cessation of limb movements.

- When the head is supported in the midline the newborn infant will look at the face of a caregiver for extended periods of time. Infants will turn the head away when they need a break from the intensity of this focused social interaction.

- When the head is supported the newborn can move the head to bring the social partner's face into the centre of the visual field.[7]

- When paying attention to a social partner, the infant will mirror facial expressions and even stick out the tongue if this has been demonstrated.

- Newborn infants engage in sustained visual regard of their own hands. Interestingly, they also pay close attention to the hands of a caregiver. [3]

Upper Limb Posture and Movements[edit | edit source]

Movement during quiet lying[edit | edit source]

- When the newborn infant is lying quietly, the upper arms rest on the supporting surface close to the body, with the shoulders in slight external rotation, the elbows in flexion and with the hands slightly open.[5]

- Periods of lying quietly are often interspersed with large range movements of the shoulders and elbows with opening of the fingers when the elbow is extended and flexion of the fingers seen with elbow is in flexion.[8]

Spontaneous movements of the upper limbs / upper extremities (UEs)[edit | edit source]

- During these spontaneous movements of the upper limbs the infant often brings one hand into their visual field and a period of quiet may ensue as the infant pays attention to the hand. [3]

- These spontaneous movements also brings the infant's hands into contact with the face and mouth. This is a familiar experience for the infant as these movements are a common intrauterine movement pattern. [3]

- Large range movements of the shoulders and elbows are seen, with opening of the fingers when the elbow is extended and flexion of the fingers seen with elbow flexion.[9]

- “To test whether newborn babies have voluntary control over their limbs, spontaneous arm-waving movements were measured in the dark while the baby lay supine with its head turned to one side. A narrow beam of light was shone over the baby's nose or chest in such a way that the arm the baby was facing was only visible when the hand encountered the, otherwise, invisible beam of light. The results showed the babies were capable of precisely controlling the position, velocity, and deceleration of their arms so as to keep the hand visible in the light. The findings indicate that newborns can purposely control their arm movements to meet external demands and that the development of visual control of arm movement is underway soon after birth.”[10]

Spontaneous movements of the fingers[edit | edit source]

- In the first weeks infants hold the hands lightly fisted, with hand opening occurring when actively moving the upper limbs.

- With increasing frequency a variety of hand postures occur, including pointing with the forefinger, thumb to forefinger, simultaneous flexion of the forefinger and middle finger, as well as ring and little finger.

- Infants can move their fingers individually,

- They are also able to imitate a demonstration of one, two and three finger extension patterns.[11]

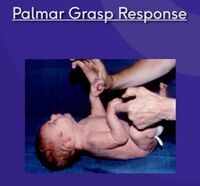

- Strong finger flexion occurs when the hand is stimulated especially on the ulnar side – known as the palmer grasp response. When traction is applied to the arm, the fingers flex synergistically with the elbow and shoulder [3]

Lower Limb Range of Motion, Posture and Kicking[edit | edit source]

- In infants born at term the range of movement (ROM) of the hips and knees is limited by muscle tightness and increased muscle tone (stiffness) in the lower limbs flexor muscles that result from the flexed posture in the restricted space in the uterus in the last weeks of intrauterine life. This is referred to as neonatal hip flexion contracture.

- During periods of relative quietening of movement

- the hips are flexed, abducted and laterally rotated and the infant lies with the feet lifted up off the supporting surface (SS)

- the knees cannot be fully extended and when passively extended they recoil back to a more flexed position.

- Newborn kicking actions[12]

- characterised by a decrease in the range of hip flexion, along with some extension of the knee

- the ankle remains in dorsiflexion with the toes in flexion. This relative extension of the hip and knee is followed by a return to the more flexed resting position.[3]

Prone[edit | edit source]

- When placed in prone, the newborn lies with head turned to one side, the hips and knees flexed and the shoulders in adduction with the elbows flexed.

- The infant is able to lift the head briefly and turn it to one side to free the airway.

- Full flexion of the hips in prone lying is associated with posterior pelvic tilt and lumbar flexion. The body weight is distributed across the head, chest and LEs.

- The UEs are held close to the torso with the shoulders in adduction, the elbows in flexion and the hands, and sometimes the forearms, resting on the supporting surface

Sitting[edit | edit source]

- When the newborn infant is supported in sitting, the neck and trunk are flexed, producing a C-shaped curve of the spine.

- The newborn can usually lift the head briefly, but cannot sustain the position. However within a week or two they are able to lift the head and hold it erect for a short period in response to an interesting visual event.

- The lower limbs are held in flexion, abduction, lateral rotation with flexion of the knees and dorsiflexion of the ankles.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Understanding Newborn Behaviour

- https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/itf09percmotdev.asp

- Motor Control and Learning

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Versfeld, P. SfA Infant Perceptual Motor Development

- ↑ Von Hofsten C. Mastering reaching and grasping: The development of manual skills in infancy. InAdvances in psychology 1989 Jan 1 (Vol. 61, pp. 223-258). North-Holland.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Versfeld, P. Newborn Infant Course. Plus. 2022

- ↑ Rönnqvist L, Hopkins B. (1998) Head position preference in the human newborn: a new look. Child Dev. 69(1):13-23.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bly L, Ariz TN. Motor skills acquisition in the first year, an illustrated guide to normal development.

- ↑ Cornwell, K. S., Fitzgerald, H. E., & Harris, L. J. (1985). On the state‐dependent nature of infant head orientation. Infant Mental Health Journal, 6(3), 137-144.

- ↑ Hirai M, Muramatsu Y, Nakamura M. Developmental changes in orienting towards faces: A behavioral and eye-tracking study. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2020 Mar;44(2):157-65.

- ↑ von Hofsten C, Rönnqvist L. (1993) The structuring of neonatal arm movements. Child Dev. 64(4):1046-57

- ↑ von Hofsten C. Early development of grasping an object in space-time. Vision and action: The control of grasping. 1990:65-79.

- ↑ Van der Meer, a L. (1997). Keeping the arm in the limelight: advanced visual control of arm movements in neonates. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology : EJPN : Official Journal of the European Paediatric Neurology Society, 1(4), 103–8.

- ↑ Nagy E, Pal A, Orvos H. (2014) Learning to imitate individual finger movements by the human neonate. Dev Sci. 17(6):841-57.

- ↑ Chen CY, Harrison T, McNally M, Heathcock JC. Preliminary evidence of an association between spontaneous kicking and learning in infants between 3-4 months of age. Braz J Phys Ther. 2021 May-Jun;25(3):329-335.