The Role of Occupational Therapy in Acute Spinal Cord Injury

Original Editor - Ewa Jaraczewska based on the course by Wendy Oelofse

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell, Tarina van der Stockt, Aminat Abolade and Jorge Rodríguez Palomino

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation process usually includes the acute, subacute and chronic phases.[1] The definition of each of these phases varies. However, the natural neurological recovery process usually sets the timing for each phase. The acute and subacute periods last around 18 months post-injury and are followed by the chronic stage when neurological recovery has plateaued.[2] During the acute spinal cord injury phase, the focus is on:[1]

- Preventing secondary complications

- Promoting and enhancing neurological recovery

- Maximising function

- Initiating activities leading to the long-term maintenance of health and function

Occupational therapists (OT) belong to the multidisciplinary team in spinal cord injury. Their role in the rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injury includes:[3]

- Enhancing patients' daily life activity execution and fine movement

- Teaching patients how to use compensatory strategies

- Finding solutions to help patients adapt their environment to fulfil the overall goal of achieving total social inclusion

The Acute Phase of Spinal Cord Injury[edit | edit source]

The acute phase of spinal cord injury occurs immediately after the injury and results from the initial trauma.[4] During this traumatic event, the spinal cord can become compressed, sheared, lacerated, stretched, and distracted. Its vascular supply can also haemorrhage or become constricted. Therefore, the first response to SCI includes resuscitation, stabilisation, and critical care to assess and localise specific injuries.[5] The patient is initially immobilised, and rehabilitation begins when the spinal cord undergoes stabilisation. This occurs when the patient is still in the intensive care unit (ICU). Secondary complications arising in the acute phase of spinal cord injury include:[6]

- Disruption of the blood-spinal cord barrier, which leads to the infiltration of inflammatory cells

- The release of inflammatory cytokines

- Initiation of proapoptotic signalling cascades

- Release of excitatory neurotransmitters causing excitotoxicity and ischaemia[6]

Regardless of the patient's initial intervention in a specialised SCI unit or a non-specific unit, the intervention provided by all team members should remain the same.[7] Clinical strategies in the management of acute spinal cord injury are as follows:

- Surgical decompression to provide relief from mechanical pressure[6]

- Inhibition of the inflammatory response which contributes to secondary damage in SCI[6]

- Blood pressure management to decrease the effect of hypotension leading to spinal cord ischaemia and secondary damage[6]

- Variety of pharmacological management (most of them in clinical trials) to reduce neuronal loss, minimise lesion size, promote tissue sparing, reduce inflammation and excitotoxicity, stimulate axonal regeneration, facilitate survival of injured neurons, and stimulate neural regeneration and axonal growth[6]

- Cell-based therapies modulate the inflammatory response, providing trophic support, axon remyelination, and neuronal regeneration[6]

- The use of biomaterials to guide axonal regrowth (clinical trial)

- Physiological approaches, including:[6]

- Therapeutic hypothermia to inhibit the systemic inflammatory response

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage to improve spinal cord perfusion

Occupational Therapy[edit | edit source]

It is difficult to find a single definition of occupational therapy (OT) which captures its complexity. As a result, several countries have not yet come up with a description of occupational therapy.

The following definition is provided by the World Federation of Occupational Therapists:

"Occupational therapy is a client-centred health profession concerned with promoting health and wellbeing through occupation. The primary goal of occupational therapy is to enable people to participate in the activities of everyday life. Occupational therapists achieve this outcome by working with people and communities to enhance their ability to engage in the occupations they want to, need to, or are expected to do, or by modifying the occupation or the environment to better support their occupational engagement".[8]

Occupational therapists are part of the multidisciplinary spinal cord injury team. During the acute phase, this team can consist of:

- Surgeon – spine / neurology / orthopaedics

- Physician – rehabilitation, other specialists (intensivist and neurologist)

- Nurse

- Patient care technician / patient care assistant

- Physiotherapist / physical therapist

- Occupational therapist

- Speech therapist / speech language pathologist

- Social worker / case manager

- Clinical psychologist

The Role of the OT in Spinal Cord Injury[edit | edit source]

When rehabilitating individuals with a spinal cord injury, occupational therapists have an "information-giving' role, as opposed to a "decision-making" role.[9] This approach allows for a non-dependent relationship between the patient and the clinician. It facilitates communication as the patient develops informed decision-making skills.[9] Active participation in their care during the acute phase of spinal cord injury will help patients build future skills in negotiating environmental barriers, avoiding preventable medical complications and solving problems following discharge from the hospital or rehabilitation centres.[9]

“Regardless of the physical ability of a person with SCI, he or she can still be in control of directing others to assist in this task unless the person with the SCI is cognitively or intellectually impaired” [10]

Therapeutic Management in Acute Spinal Cord Injury[edit | edit source]

General Guidelines[7][edit | edit source]

- Always seek medical clearance before mobilising a patient with a spinal cord injury

- Understand and know the medical precautions

- Educate, but do not overwhelm with too much information

- When teaching skills, make sessions practical and link to a daily routine

- Involve the patient and family from the beginning

- Be flexible with your time

- Multiple brief sessions during the day are a good solution: e.g. two 15 minutes sessions per day may be helpful

Preventing Secondary Complications[edit | edit source]

Skin Management[edit | edit source]

Positioning in bed and in a wheelchair:

Goals for proper positioning in bed:[11]

- Prevent pressure ulcers

- Maintain range of motion

- Prevent pulmonary complications

There is a lack of conclusive guidelines on positioning or repositioning techniques for pressure ulcer prevention in bed. These strategies vary greatly and should be flexible. However, education remains the most potent strategy for the best outcome.

General guidelines:

- Avoid the 90° lateral position because of the risk of pressure ulcers developing over the trochanters.[12]

- Maintain the lowest degree of head of bed elevation consistent with the patient's medical condition.[7]

- Avoid raising the head of the bed 30 degrees or higher as it increases the peak interface pressure between the skin at the sacral area and the support surface.

- Repositioning frequency depends on the individual's tissue tolerance, activity level, general medical condition, observed skin condition, and the type of support surface used.[11]

- Avoid dragging the patient across the surface while turning in bed to prevent shear-related injuries. Use sheets to lift the patient. Avoiding shear is also vital in minimising skin breakdown during transfers between surfaces.[7]

Goals for proper wheelchair positioning:

- Provide postural support

- Maintain tissue integrity

- Prevent tissue trauma

Skin protection is optimised when the patient sits fully upright in an appropriate wheelchair with a specialised pressure cushion. Please note that if the patient's pelvis is in a posterior pelvic tilt, this places increased pressure over the sacrum.

General guidelines:[11]

- Re-evaluate the wheelchair / seating support surface and associated equipment periodically for posture and pressure redistribution

- Select a pressure redistribution cushion

- Provide adequate seat tilt to prevent the patient from sliding forward in the wheelchair / chair

- Adjust footrests and armrests to maintain proper posture and pressure redistribution

- Avoid elevating leg rests if the individual has inadequate hamstring length

- Tilt the wheelchair before reclining

- Do not use a ring or doughnut cushion

Instruction on pressure relief technique:[7]

- Teach individuals to perform or direct the most appropriate pressure-relieving manoeuvres

- Establish pressure relief schedules that prescribe the frequency and duration of effective weight shifts

Conduct and instruct patients on how to perform visual and tactile skin inspection:[7]

- Incorporate this inspection into the patient's the daily routine: e.g. inspect the skin before or after washing

- Provide the patient with equipment for skin inspection: e.g. long-handle mirror, camera

Practise good hygiene:[7]

- Educate the patient and family on a good hygiene routine

- Clean the area immediately after bowel movements

- Keep the genital area clean and dry

Prevent oedema:

Limited muscle activity as a result of paralysis reduces venous and lymphatic return capacity, which leads to oedema. When left unmanaged, oedema can affect hand position, including: a loss of the tenodesis grip, with the wrist in flexion, metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP) in hyperextension, thumb in adduction, and flexion of proximal and distal interphalangeal (PIP and DIP) joint.[13] Oedema prevention is essential to maximise the patient's ability to use their hands:[13]

- Ensure proper feet and arm positioning in the wheelchair (leg rests, armrests)

- Elevate arms in bed (propping on the pillows)

- Use custom-made hand splints

- Splinting is considered standard care for individuals with cervical spinal cord injury[14]

- Hand splinting should start as soon as possible after injury[14]

- Resting hand splints are recommended for night use in all levels of cervical SCI[14]

- Wrist splints are recommended for daily use in individuals without active wrist movement[14]

- Static splinting with firm volar pressure maintains range of motion and slight shortening of the finger flexors

- Apply compression gloves

Prevention of Respiratory Complications[edit | edit source]

Respiratory complications during the acute phase of hospitalisation are a primary determinant of length of stay and cost of hospitalisation among patients with acute tetraplegia.[15] Most common respiratory complications with C1-C4 spinal cord injury include (from the most to the least frequent):[16]

According to Berlly and Shem,[17] 65% of patients with T1-T12 spinal cord injury have severe respiratory complications.

General guidelines for prevention of respiratory complications:

- Start immediately for all patients with acute spinal cord injury

- Help with secretion mobilisation:

- Consider contraindications for assisted coughing, including unstable spine in traction, internal abdominal complications, fractured ribs, and a recently placed vena cava filter[17]

- Manual cough assist[16]

- Postural drainage[16]

- Work with the team on safe swallowing:

You can learn more about respiratory complications in SCI in this course by Melanie Harding (Skeen): Respiratory Management Following a Spinal Cord Injury.

Prevention of Joint Contractures[edit | edit source]

Upper and lower extremity contractures can develop in acute spinal cord injury due to:[18]

- Static positioning because of an inability to move joints throughout the normal range

- An imbalance between the agonist and antagonist muscles due to asymmetries in strength in incomplete SCI

- Oedema, which alters an individual's hand and wrist resting position

- Development of spasticity[19]

The presence of joint contractures can be associated with decreased functional ability. Research shows that contractures greatly influence quality of life (QoL).[20] They can lead to pain and deformity, and ultimately, contribute to decreased levels of independence.[21]

Prevention strategies include:

- Positioning:[7]

- Position the arm in abduction and external rotation while the patient is supine

- Maintain fingers in a curled position and the wrist in slight extension for patients with C6/7 spinal cord injury to encourage a tenodesis grasp

- Maintain arm in extension for patients with C5/C6 spinal cord injury to avoid positioning the arm in flexion

- Pain management:[7]

- Proper handling techniques during transfers and positional changes:

- Do not pull on the patient's arm when positioning or transferring them

- Ensure that the whole arm is supported in all positions to avoid gravity pulling on joints and causing pain

- Proper handling techniques during transfers and positional changes:

- Passive range of motion:[7]

- Ensure the wrist remains mobile

- Encourage active wrist extension

- Do not overstretch the finger flexors – do not stretch / straighten the fingers with the wrist in extension

- Always straighten the fingers with the wrist in flexion and curl fingers with the wrist in extension

- Educate the patient and their family on proper range of motion techniques

- Maintain web space – splinting might be required

Mobilisation[edit | edit source]

Goals for early mobilisation:[7]

- To reduce respiratory complications

- To reduce pressure over the sacrum

- To improve psychological well-being

- To assist with bowel management

Guidelines for early mobilisation:[7]

- Understand and adhere to early mobilisation precautions

- Ensure that the wheelchair and seating system are appropriate for the patient's condition, size and their ability to direct or perform pressure relief

- Know how to manage postural hypotension:

- Slow and gradual mobilisation

- Use abdominal binder as appropriate

- Consider lower limb wrapping or the use of compression stockings

- Know recovery techniques in case a patient faints:

- Tilt the chair

- Lift both legs above the heart

- Slowly press on the patient’s abdomen

- Develop a sitting schedule. For example, out of bed for meal time.

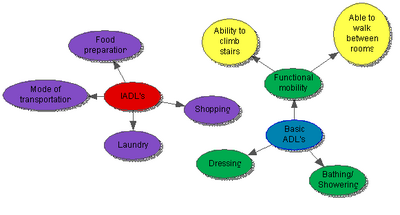

Retraining for Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)[edit | edit source]

"The occupational therapist (OT) role is to enable the person with SCI to resume participation in their meaningful occupations such as work, activities of daily living and leisure."[22]

Goals for retraining for ADLs:

- To be able to control the hospital environment (call button, telephone, bed controls[7])

- To be able to direct all aspects of basic ADLs

Guidelines for retraining ADLs:

- Involve the patient in decision-making (patient-centred approach)[22]

- Ensure access to adequate resources[22]

- Collaborate with the multidisciplinary team to improve outcomes[22]

- Know your patient's functional expectations and pre-morbid level of function[7]

- Consider cultural factors, patient's views and expectations[22][7]

ADL retraining:

- Range of motion and strength training as muscle strength is a prerequisite for training activities of daily living and self-care, including feeding, bathing, dressing and grooming[23]

- Provide the patient with essential environmental controls (call buttons, bed controls)

- Facilitate communication for ventilated patients: use of communication boards or picture cards

- Ensure that the patient is oriented daily to time, place, day of the week, etc.

Psychological Support[edit | edit source]

Goals for psychological support:[7]

- To encourage effective coping strategies

- To encourage health-promotion behaviours

- To promote participation and independence

Guidelines for psychological support of the patient and their families:

- Meet the patient's and family members' information needs[25]

- Discuss the patient’s recovery prognosis, the impact of SCI on the patient’s functional independence, how to manage secondary complications, and what to expect in rehabilitation[25]

- Continuously repeat, reinforce and clarify information provided[25]

- Promote realistic hope and focus on what the patient is capable of doing while being honest about their prognosis[25]

- Consider the spiritual needs of patients and their family members during acute spinal cord injury[26]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Preservation of Upper Limb Function Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Early acute management in adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31(4):403-79.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Burns AS, Marino RJ, Kalsi-Ryan S, Middleton JW, Tetreault LA, Dettori JR, Mihalovich KE, Fehlings MG. Type and Timing of Rehabilitation Following Acute and Subacute Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review. Global Spine J. 2017 Sep;7(3 Suppl):175S-194S.

- ↑ Burns AS, Marino RJ, Flanders AE, Flett H. Clinical diagnosis and prognosis following spinal cord injury. Handb Clin Neurol. 2012;109:47-62.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Mendoza B , Santiago-Tovar PA , Guerrero-Godinez MA , García-Vences E. Rehabilitation Therapies in Spinal Cord Injury Patients. In: Arias, J. J. A. I. , Ramos, C. A. C. , editors. Paraplegia [Internet]. London: IntechOpen; 2020 [cited 2022 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/72439

- ↑ Alizadeh A, Dyck SM, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Models and Acute Injury Mechanisms. Front Neurol. 2019 Mar 22;10:282.

- ↑ Ashammakhi N, Kim HJ, Ehsanipour A, Bierman RD, Kaarela O, Xue C, Khademhosseini A, Seidlits SK. Regenerative therapies for spinal cord injury. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 2019 Dec 1;25(6):471-91.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Donovan J, Kirshblum S. Clinical trials in traumatic spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2018 Jul;15(3):654-68.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 Oelofse W. The Role of Occupational Therapy in Acute Spinal Cord Injury Course. Plus 2022

- ↑ Definitions of occupational therapy from member organisations. World Federation of Occupational Therapists. Available from https://wfot.org/resources/definitions-of-occupational-therapy-from-member-organisations [last access 28.08.2022]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Hammell KW. Spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Springer; 2013 Dec 11.

- ↑ Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines. Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment following spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2001 Spring;24 Suppl 1:S40-101.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Available from https://www.epuap.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/quick-reference-guide-digital-npuap-epuap-pppia-jan2016.pdf [last access 28.08.2022]

- ↑ Groah SL, Schladen M, Pineda CG, Hsieh CH. Prevention of pressure ulcers among people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Pm&r. 2015 Jun 1;7(6):613-36.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Dunn J, Wangdell J. Improving upper limb function. Rehabilitation in Spinal Cord Injuries. 2020 Feb 1:372.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Frye SK, Geigle PR. Current US splinting practices for individuals with cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Series and Cases. 2020 Jun 17;6(1):1-7.

- ↑ Winslow C, Bode RK, Felton D, Chen D, Meyer Jr PR. Impact of respiratory complications on length of stay and hospital costs in acute cervical spine injury. Chest. 2002 May 1;121(5):1548-54.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Tollefsen E, Fondenes O. Respiratory complications associated with spinal cord injury. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2012 May 15.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Berlly M, Shem K. Respiratory management during the first five days after spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(4):309-18.

- ↑ Skalsky AJ, McDonald CM. Prevention and management of limb contractures in neuromuscular diseases. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2012 Aug;23(3):675-87.

- ↑ Barbosa PH, Glinsky JV, Fachin-Martins E, Harvey LA. Physiotherapy interventions for the treatment of spasticity in people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2021 Mar;59(3):236-47.

- ↑ Sturm C, Gutenbrunner CM, Egen C, Geng V, Lemhöfer C, Kalke YB, Korallus C, Thietje R, Liebscher T, Abel R, Bökel A. Which factors have an association to the Quality of Life (QoL) of people with acquired Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)? A cross-sectional explorative observational study. Spinal Cord. 2021 Aug;59(8):925-32.

- ↑ Perrouin-Verbe B, Lefevre C, Kieny P, Gross R, Reiss B, Le Fort M. Spinal cord injury: A multisystem physiological impairment/dysfunction. Revue Neurologique. 2021 May 1;177(5):594-605.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Snyman A, de Bruyn J, Buys T. Goal setting practices of occupational therapists in spinal cord injury rehabilitation in Gauteng, South Africa. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2021 Jun 1;7(1):48.

- ↑ Kessler TM, Traini LR, Welk B, Schneider MP, Thavaseelan J, Curt A. Early neurological care of patients with spinal cord injury. World Journal of Urology. 2018 Oct;36(10):1529-36.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Hosseini SR, Valizad-Hasanloei MA, Feizi A. The Effect of Using Communication Boards on Ease of Communication and Anxiety in Mechanically Ventilated Conscious Patients Admitted to Intensive Care Units. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2018 Sep-Oct;23(5):358-362.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Cogley C, D’Alton P, Nolan M, Smith E. “You were lying in limbo, and you knew nothing”: a thematic analysis of the information needs of spinal cord injured patients and family members in acute care. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2021 Aug 30:1-1.

- ↑ Jones KF, Dorsett P, Briggs L, Simpson GK. The role of spirituality in spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation: exploring health professional perspectives. Spinal Cord Series and Cases. 2018 Jun 26;4(1):1-6.