Flexor Digitorum Longus

Original Editor - George Prudden

Top Contributors - George Prudden, Kim Jackson, Abbey Wright, Pinar Kisacik, Patti Cavaleri, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas and WikiSysop;

Description[edit | edit source]

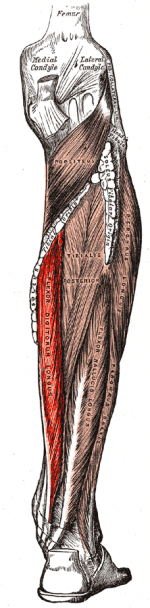

The flexor digitorum longus (FDL) is part of the deep muscle group of the posterior compartment of the lower leg[1]. Its primary action is flexion of digits 2-5 in the foot.

Origin[edit | edit source]

Medial portion of the posterior surface of the tibia, inferior to the soleal line. It is also connected to the fibula by a broad tendon[1].

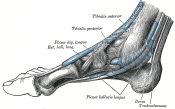

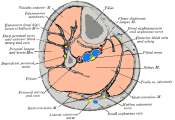

The tendon then passes laterally to tibialis posterior tendon where it then situated deep to the flexor retinaculum lying in its own synovial sheath along the medial aspect of the sustentaculum tali. Beyond this point it is difficult to palpate as it enters the sole of the foot, deep to the abductor hallucis where is crosses forwards and laterally on the plantar aspect.

Halfway along the sole, on the lateral side the tendon merges with flexor accessorius and divides into 4 individual tendons for the second to fifth toes. The lumbricals arise distal to the attachment of the flexor accessorius.[2]

Insertion[edit | edit source]

On the plantar surface at the base of the distal phalanges of the second, third, fourth and fifth toes[1].

Nerve[edit | edit source]

Tibial nerve (S2 and S3)[1].

Cutaneous supply on the medial and posterior aspect of the calf and sole from L4, L5 and S1.

Artery[edit | edit source]

Posterior tibial artery[3]

Function[edit | edit source]

Flexes the second to fifth toes first at the distal interphalangeal joint, then the proximal interphalangeal joint and finally the metatarsophalangeal joint. Aids with plantarflexion of the foot at the ankle.

When the ankle is plantarflexed, the muscle is unable to perform its flexion action of the toes[2]

Clinical relevance[edit | edit source]

During the propulsion phase of walking, running or jumping, flexor digitorum longus pulls the toes downwards towards the ground to attain maximal grip and thrust during toe-off. During standing the muscle aids with balance by gripping the ground.[2]

Fractures of the sustentaculum tali can cause entrapment of the flexor hallucis longus or flexor digitorum longus tendons amongst other abnormalities that may indicate reconstructive surgery. Post-operative management includes the use of a lower leg splint for 5-7 days, partial weight-bearing with 20 kg for 6-8 weeks in the patient's own footwear, early range of motion exercises of the ankle, subtalar and mid-tarsal joints. Outcomes are generally good with those sustaining isolated fractures performing better.[4]

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Palpation[edit | edit source]

It is near impossible to locate the origin due to its depth under the soleus muscle. The insertional tendon is also deep but can be identified as it passes alongside the sustentaculum tali within the posterior tarsal tunnel.

Muscle strength[edit | edit source]

Resisted flexion of second to fifth toes with the foot in neutral or dorsiflexion.

Length[edit | edit source]

In supine or seated, with ankle in dorsiflexed position. Stabilise proximal bone of joint to be measured. Extend the joint to be measured through available ROM.[5]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Strengthening[edit | edit source]

A common exercise for foot strength is performed using a towel. Ask the patient to sit and place a towel under their foot, then ask the patient to grip the towel with their toes thereby moving the towel along the floor.

The muscle can be strengthened by utilising its role in balance. Providing a patient with a suitably challenging balance exercise such as using wobble board or foam pad makes exercise more functional.

Further in rehabilitation, walking or running on different surfaces such as grass or sand will further challenge the function of flexor digitorum longus.

Stretching[edit | edit source]

A stretch can be performed by pulling the toes into a extended position and the ankle into a dorsiflexed position. Similar to strengthening, a towel may be useful if the patient is struggling to reach forward. It can be wrapped around the toes and ball of the foot.

Resources[edit | edit source]

|

|

|

|

See also[edit | edit source]

- Flexor hallucis longus

- The Os Trigonum Syndrome

- Tarsal Tunnel syndrome

- Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction

- Ankle & Foot

- Compartment Syndrome of the Foot

- Ankle Impingement

- Hallux Valgus

- Ankle Joint

- Congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Moore KL, Dalley AF, R. AAM, Moore KL. Moore clinically oriented anatomy. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Palastanga N, Soames R. Anatomy and Human Movement: Structure and Function. 6th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2012.

- ↑ Saladin K. Anatomy & physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010.

- ↑ Dürr C, Zwipp H, Rammelt S. Fractures of the sustentaculum tali. Operative Orthopädie und Traumatologie. 2013 Dec;25(6):569–78.

- ↑ Reese NB, Bandy WD, B WD, Y MM. Joint range of motion and muscle length testing. Philadelphia: Saunders (W.B.) Co; 2002 Jan 15. ISBN: 9780721689425.