Core Strengthening

Original Editor - Deborah Riczo, Wanda van Niekerk

Top Contributors - Wanda van Niekerk, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Vidya Acharya and Olajumoke Ogunleye

What is the Core?[edit | edit source]

Although this seems like a straightforward question, "What is the Core?", there exists discrepancies not only in consumer media, but also among researchers and practicing healthcare providers. Therefore discrepancies also exist in how to effectively strengthen the core.

The core muscles are involved in maintaining spinal and pelvic stability and can be divided into two groups, according to function.[1] The first group of muscles is the inner or deep core muscles. This group of muscles is also known as the local stabilising muscles.[1] Hodges et al (1996)[2] showed that the inner core acts in an anticipatory way and that these muscles are activated and fire before the global muscles are activated.

The inner core muscles include:[3][4]

- Pelvic floor

- Transversus abdominis

- Internal Obliques

- Multifidus

- Diaphragm

- Some literature also includes the deep fibres of the psoas and the deep hip rotators as part of the inner core.

The outer core muscles or the global muscles are also referred to as the “movers” and include:[1][3]

Integrated Model of Function[edit | edit source]

When the inner and outer (or local and global) core muscles function normally, segmental spinal stability is maintained, the spine and pelvic area is protected and the stress or load that may influence the lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral discs are reduced.[1] In the case of dysfunction, such as a weak inner core, the outer core compensates for this weakness. Although the outer core muscles’ main function is movement and not stability it is able to contribute to stability with unexpected tasks or overload. As a result of this, splinting occurs and this leads to neuromusculoskeletal issues such as muscle spasms, neural compression and pain.[5]

Abdominal Canister[edit | edit source]

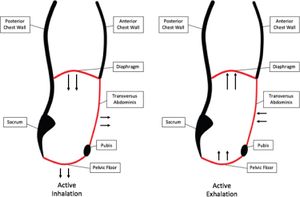

The inner core muscles can be thought of as an abdominal canister with muscles forming the top and sides of the canister.

The abdominal canister functions similar to the action of a piston. As the diaphragm expands during inspiration, it lowers and presses down on the contents of the abdomen.[6] To allow for this pressure, the pelvic floor muscles relax and elongate. Below is a short summary of how the abdominal canister functions to facilitate breathing:[6]

Inspiration

- Diaphragm contracts and the dome shape flattens

- Chest wall expands

- Creates negative pressure in the thorax, drawing air into the lungs

- Descent of diaphragm also causes expansion of abdominal wall and pelvic floor, due to increase in abdominal pressure

Exhalation (during quiet breathing):

- Diaphragm recoils to resting position

- Passive expulsion of air from the lungs

- The abdominal wall and pelvic floor gently contract to return to resting position

Active exhalation (increased respiratory demand):

- Increases air expulsion efficiency to accelerate gas exchange

- Accessory respiratory muscles contract to speed up diaphragm elevation

- Pelvic floor and abdominal muscles are included within these accessory muscles – as they contract more forcefully – create a cranially directed increase in intra-abdominal pressure – this assists with diaphragm elevation.[6]

Activating the Core[7][edit | edit source]

Optimal Posture and Conditions to Monitor while Activating the Core[edit | edit source]

- Posture of the rib cage over pelvis

- Maximum activation of the inner core occurs when the rib cage is in neutral over the pelvis, not positioned in extension or flexion (breastbone too elevated or depressed)[8]

- Conditions to monitor

- Abdominal wall

- Doming in the abdominal muscles

- Monitor:

- Breath-holding and creating a vacuum

- Less than optimal breathing pattern

- Exercise too difficult

- Rectus abdominis or other weakness resulting in a poor pattern

- Monitor:

- Doming in the abdominal muscles

- Pelvic floor symptoms

- pressure/bulging in the perineum area (symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse)

- any incontinence or pelvic pain[9]

- Breath-holding and creating a vacuum

- Less than optimal breathing pattern

- Exercise too difficult

- Rectus abdominis or other weakness resulting in a poor pattern[9]

- Abdominal wall

Activating the Core in a Static Position[7][10][edit | edit source]

- Supine position

- Take note when prescribing exercises in the supine position: “Maintaining a supine position during exercise after 20 weeks of gestation may result in decreased venous return due to aortocaval compression from the gravid uterus, leading to hypotension, and this hemodynamic change should be considered when prescribing exercise modifications in pregnancy.”[11]

- Position

- Knees can be straight or bent

- Pillow/wedge under the hips with very weak pelvic floor muscles

- gravity is assisting and to take the weight off the pelvic floor[12]

- Inhalation

- Activate the diaphragm with diaphragmatic breath

- Imagery suggestions

- umbrella imagery to expand ribcage (like opening up an umbrella)

- Imagery suggestions

- Activate the diaphragm with diaphragmatic breath

- Exhalation

- Activate the pelvic floor through pursed lips or hissing sound

- Imagery suggestions for exhale

- Quieting a child, shushing sound

- Blowing up a balloon

- Imagery suggestions for activating pelvic floor (see note below)

- Stopping flatulence or the flow of urine

- Holding in a tampon

- Lifting testicles up as if walking into cold water

- Imagery suggestions for activating transversus abdominis

- zip up tight jeans

- drawing in manoeuvre

- tensioning wire across lower abdomen, between ASIS's

- Imagery suggestions for exhale

- Activate the pelvic floor through pursed lips or hissing sound

- Static core activation can be performed in various positions, for example:[7][10][13]

- Position

- Take note when prescribing exercises in the supine position: “Maintaining a supine position during exercise after 20 weeks of gestation may result in decreased venous return due to aortocaval compression from the gravid uterus, leading to hypotension, and this hemodynamic change should be considered when prescribing exercise modifications in pregnancy.”[11]

Note: Refrain from adding pelvic floor activation with symptoms of an overactive pelvic floor such as:

- chronic pelvic pain

- dyspareunia (painful intercourse)

- pain with bowel movements

- pain increasing with a pelvic floor contraction

- In such cases, the patient should refrain from adding the pelvic floor contraction and rather focus on relaxing the pelvic floor.[15]

- Imagery suggestions:

- Opening up like a jelly fish

- Referral to a pelvic floor/pelvic health physiotherapist would be indicated for further treatment

- Imagery suggestions:

As in any exercise program to produce strengthening, the frequency and number of repetitions should be individualized to the tolerance of the patient, but should ideally be done within the same exercise session to produce fatigue of the muscles (in a variety of positions). Instead of giving 3 sets of 10 of one position of the same static exercise, consider a set of 10 in 3 or 4 different positions.[7] [10]

Activating the Core in a Dynamic Position[edit | edit source]

- Core strengthening is progressed by adding movement of arms and legs.[7][10][16]

- Important to monitor/ encourage breathing pattern for core activation as described above throughout these progressions

- Alternating movements from side to side is preferred before progressing to completing a full set on one side[7]

- Simulates real life movements as in walking

- Practices transitional movements in a safe position

- More difficult to do repetitions on one side due to fatigue of muscles

- Exercises done in various positions due to effects of gravity and benefits to patient's perception of their body in space

- Monitor the patient's pelvis for excessive movement during movement of the limb and modify exercise if needed.

- Supine exercises

- Take note when prescribing exercises in the supine position: “Maintaining a supine position during exercise after 20 weeks of gestation may result in decreased venous return due to aortocaval compression from the gravid uterus, leading to hypotension, and this hemodynamic change should be considered when prescribing exercise modifications in pregnancy.”[11]

- Patient monitors movement of the ASIS's while moving the legs

- Goal is to keep the ASIS's stable/quiet

- Exercise modification is needed with too much movement

- Progression examples

- Alternate arm reaches

- Alternate knee lifts

- Combine opposite arm and leg

- Knee extension as a progression from alternate knees in supine

- Alternate straight leg raise

- Prone

- Glut sets with core activation

- Alternating hip extension

- Modification

- closed chain – keep toe on the ground and lift the knee and gluteus maximus

- Modification

- Alternate arms/legs

- Pillow may be needed under stomach

- 4-point kneeling

- Avoid this position in a patient with large DRA (diastasis recti abdominis) (clinical judgement based on integrity of tensioning between sides of the linea alba)

- Adding alternate arms

- Alternate arms and legs

- ½ kneeling

- Good position for core strengthening

- Incorporates balance training

- Involves asymmetrical gluteal activation

- Alternate arms reach – aim for good lengthening in latissimus dorsi

- Trunk rotation

- Can add light arm weights

- Standing

- Higher-level Exercises

- Plank on elbows

- Start off on knees, progress to on toes

- Plank on elbows

- Side-plank

- Single leg bridge

- 4-point alternate arm/leg balance

- Progress to whole-body movements, agility and balance

- Lunges

- Stepping

- Stepping to the side

- Side squats

- High stepping, hand to opposite heel while moving

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Core strengthening activates the inner core as well as strengthens the outer core. Modifications and breathing strategies are indicated with symptoms of doming or bulging of abdominals, leaking urine or stool and increasing pain. A variety of positions during core strengthening considers the effects of gravity on the core as well as assists with the patient’s body awareness in space. The above lists are meant to be suggested options of progression and are meant to be moved through as quickly as possible. This will depend on the patient’s clinical presentation/performance/adherence.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Chang WD, Lin HY, Lai PT. Core strength training for patients with chronic low back pain. Journal of physical therapy science. 2015;27(3):619-22.

- ↑ Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine. 1996 Nov 15;21(22):2640-50.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Akuthota V, Ferreiro A, Moore T, Fredericson M. Core stability exercise principles. Current sports medicine reports. 2008 Jan 1;7(1):39-44.

- ↑ Saiklang P, Puntumetakul R, Swangnetr Neubert M, Boucaut R. The immediate effect of the abdominal drawing-in manoeuver technique on stature change in seated sedentary workers with chronic low back pain. Ergonomics. 2021 Jan 2;64(1):55-68.

- ↑ Key J. ‘The core’: understanding it, and retraining its dysfunction. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2013 Oct 1;17(4):541-59.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Siracusa C, Gray A. Pelvic Floor Considerations in COVID-19. Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 2020 Oct;44(4):144.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Riczo DB. Back & Pelvic Girdle Pain in Pregnancy & Postpartum: Find Relief Using the Pelvic Girdle Musculoskeletal Method. Orthopedic Physical Therapy Products; 2020.

- ↑ Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle E-Book: An integration of clinical expertise and research. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011 Oct 28.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Casey EK, Temme K. Pelvic floor muscle function and urinary incontinence in the female athlete. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2017 Oct 2;45(4):399-407.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Riczo DB. Sacroiliac Pain. Orthopedic Physical Therapy Products; 2018

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Syed H, Slayman T, Thoma KD. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 804: Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2021 Feb 1;137(2):375-6.

- ↑ Deborah Riczo. Core Strengthening. Plus , Course. 2021.

- ↑ Moghadam N, Ghaffari MS, Noormohammadpour P, Rostami M, Zarei M, Moosavi M, Kordi R. Comparison of the recruitment of transverse abdominis through drawing-in and bracing in different core stability training positions. Journal of exercise rehabilitation. 2019 Dec;15(6):819.

- ↑ Escamilla RF, Lewis C, Pecson A, Imamura R, Andrews JR. Muscle activation among supine, prone, and side position exercises with and without a Swiss ball. Sports health. 2016 Jul;8(4):372-9.

- ↑ Stein A, Hughes M. A classical physical therapy approach to the overactive pelvic floor. The overactive pelvic floor. 2016:265-74.

- ↑ Escriche-Escuder A, Calatayud J, Aiguadé R, Andersen LL, Ezzatvar Y, Casaña J. Core Muscle Activity Assessed by Electromyography During Exercises for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2019 Aug 1;41(4):55-69.

- ↑ Cakmak B, Ribeiro AP, Inanir A. Postural balance and the risk of falling during pregnancy. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2016 May 18;29(10):1623-5.

- ↑ Rehab my patient. Core control 7. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MAzd-kxnH18 (last accessed 8 April 2021)

- ↑ Rehab my patient. How to improve lower abdominal strength 2. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I665l7U4oOA&t=34s. (last accessed 8 April 2021)

- ↑ Rehab my patient. BOSU balance catching a ball. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T69RBvA5Jek&t=14s. (last accessed 8 April 2021)