Anal Cancer

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Anal cancer is a rare cancer, accounting for about 2% of all gastrointestinal tract malignancies. Its incidence increased by 2.7% annually over the last 10 years. It frequently faces considerable stigma, largely attributed to its connections with sexual practices and the sexual identities of individuals. The occurrence of anal cancer shows different patterns across Western countries. Statistics indicate that in the UK, Netherlands, Australia, and the USA, the frequency ranges from 0.7 to 1.7 cases annually per 100,000 individuals. In 2023 the United States estimated around 1.96 million new cases of cancer in total, with anal cancer constituting approximately 0.5% of these cases, equating to about 9,760 instances. Additionally, out of an estimated 609,820 cancer-related deaths expected in the same year, around 0.3% are anticipated to result from anal cancer [1].

In the majority of countries, women tend to have a higher rates of incidence. In women under 40, anal cancer is rare, with its occurrence increasing with aging. [2] Those women who are over 65 are most affected, then the 50-64 age range, it is thought to be mainly linked to rising HPV infection rates [3].

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

HPV infection considered as a primary risk factor: Human papillomavirus (HPV), especially HPV16, is involved in about 80-85% of anal cancer cases [4]. The persistence of HPV infection, often associated with factors like anal intercourse and multiple sexual partners, increases the likelihood of anal cancer [5]. HPV infection particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18, these stereotypes of HPV-16 and HPV-18 can integrate their DNA into the host cells in the anal mucosa, leading to cellular changes [6].

Immunosuppression: risk of anal cancer is significantly driven by weakened immune systems, the weakened immune response fails to adequately control HPV infection, increasing the risk of malignant changes [5].

Chronic Inflammation and Cellular Changes: Persistent inflammation in the anal region, often due to chronic HPV infection, can lead to precancerous changes known as anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN), which can eventually progress to invasive cancer.

Additional risk factors: men who have sex with men, women with HPV-related gynecological cancers or lesions, people with solid organ transplants or autoimmune disorders, older age, lifetime number of sexual partners, female, and smoking habits of individuals are at a higher risk for anal cancer [7].

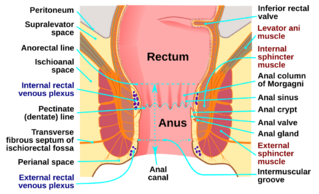

Common Types of Anal Cancer[edit | edit source]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) it was classified into three main groups: epithelial, mesenchymal, and secondary tumors and the epithelial tumors were subdivided into malignant and premalignant lesions.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accounts for over 80% of all anal cancer cases, and exhibits numerous characteristics common to cervical cancer. It often arises in the transformation zone between squamous and columnar epithelium and is characterised by a basement membrane that resembles those in skin adnexal and salivary gland neoplasms, lacking a myoepithelial layer. Predominantly, SCC displays squamous features, such as keratinisation and intracellular bridges, in over 90% of cases. Nonkeratinizing cancer, identified above the dentate line, falls under the same category. Distinguishing SCC, especially from conditions like poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, involves detecting cytokeratin 5 and 6 (CK5 and CK6). The diagnostic process is further aided by immunohistochemically staining for p63 protein, located on chromosome 3's long arm, a frequent site for SCC genomic amplification. This categorization now includes basaloid, transitional, and spheroidal cancer variants under SCC. Research on anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC) highlights frequent mutations in certain genes, especially in cases linked to HPV infection. These include genes in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and genes like MLL2 and MLL3[8]. HPV-negative ASCC cases often have mutations in tumor suppressor genes like TP53 and CDKN2A[8]. There's a notable difference in the expression of the PD-L1 protein between HPV-positive and HPV-negative ASCC cases, which impacts patient survival rates. However, how these genetic factors affect treatment options for anal cancer is still under investigation[9].

Anal adenocarcinoma is an uncommon type of anal cancer case and accounts for only 10-15%, it may develop in the mucosa, anal glands, or fistulae in the anal canal. It might show up close to the anal duct as either a small raised or ulcerated spot or as a mass beneath the mucosal surface. There is a noted link with both Paget's disease and Crohn's disease. Typically, adenocarcinomas that are linked with either congenital or acquired fistulae tend to produce mucin (a significant component of mucus, a slippery, protective secretion produced by glands in various parts of the body)[10].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

There is a variety in symptoms of anal cancer according to the stage of the tumor [11]:

- Anal Bleeding: it is the most frequent symptom.

- Anal/Perianal pain or painful defecation.

- Weight loss.

- Tumor detection through self-palpation.

- Foreign body sensation

- Constipation.

- Abdominal pain.

- Itching.

- Fecal incontinence.

- Inguinal lymph nodes on self palpation.

- Irregular stool.

- Vaginal stool.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

It's crucial to detect anal cancer as soon as possible. Early-stage anal cancer can be effectively treated with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, which also helps maintain bodily functions [12].

- Initial assessments are important and may include some or all of the following:

- Complete medical history.

- Physical examination.

- Digital examination for all patients.

- Gynecological examination for women.

- MRI is highly sensitive (90–100%) in detecting anal cancer, providing details on tumor location and extent, and infiltration into nearby organs and lymph nodes.

- Endoanal ultrasound for assessing tumor depth.

- Positron emissions tomography (PET) especially using 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is highly effective in cancer detection and staging, with about 98% of anal tumors detectable, it has a higher sensitivity and specificity for detecting primary tumors and inguinal lymph nodes. It has also significantly influenced treatment planning, leading to changes in the approach for many patients [13].

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Surgical Treatment[edit | edit source]

- Nowadays, small, non-poorly differentiated anal margin lesions (less than 2 cm) may be treated with local excision if it doesn't compromise sphincter function and adequate margins are possible. This will require proper staging to determine the suitability of local excision, especially to rule out lymph node involvement.

- For more advanced tumors, abdomino-perineal excision (APE) was previously the standard but is now primarily used for patients who have had prior pelvic radiation[13][6].

Chemoradiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Chemoradiotherapy (CRT) with 5-FU and mitomycin C is the primary treatment for early-stage anal cancer, demonstrating better outcomes than radiotherapy alone. Replacing MMC with cisplatin hasn't shown better results, and neo-adjuvant or maintenance chemotherapy has not improved outcomes. Capecitabine may be an alternative to infused 5-FU, based on data from rectal cancer studies[3][6].

Physical Therapy Intervention[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy plays a crucial role in enhancing the quality of life, and daily function, increasing physical activity and strength, managing pain, reducing fatigue, addressing post-surgical issues like lymphedema, and the overall health of cancer patients, although specific protocols may vary. The exercise programs should be designed based on patient conditions, existing routines, physical capabilities, and any limitations. These exercises primarily aim to reduce fatigue, optimise physical function, and ensure safety and well-being.

Pelvic floor physical therapist[edit | edit source]

- The physical therapy program starts with patient education about the best positions for bowel movements, dietary recommendations (high fiber, low fat, avoiding spicy and stimulating foods), and good bowel habits to manage urgency after meals or physical activities. In addition, educate the patient on how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles and teach them pelvic floor exercises and may also include sensory training using a rectal balloon [14].

- Different manual therapy techniques such as myofascial trigger point release, connective tissue manipulation, soft tissue mobilisation, scar and joint mobilisation can be used for the rehabilitation and managing patients with anal cancer post operative or after treatment with chemoradiation therapy.

- Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises (PFME): Following a specific protocol, patients will perform daily pelvic floor exercises. They'll also learn the knack technique to contract muscles before activities that increase abdominal pressure [14].

- Electromyographic Biofeedback and capacitive and sensory training with a balloon probe [15] to help patients recognise the urge to defecate and the maximum volume they can tolerate, teaching them to contract the sphincter in response to rectal distension [14].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Haemorrhoids if there is bleeding.

Resources[edit | edit source]

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Islami F, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bray F, Jemal A. International trends in anal cancer incidence rates. International journal of epidemiology. 2017 Jun 1;46(3):924-38.

- ↑ Kang YJ, Smith M, Canfell K. Anal cancer in high-income countries: increasing burden of disease. PLoS One. 2018 Oct 19;13(10):e0205105.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nelson RA, Levine AM, Bernstein L, Smith DD, Lai LL. Changing patterns of anal canal carcinoma in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013 Apr 4;31(12):1569.

- ↑ Lin C, Franceschi S, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus types from infection to cancer in the anus, according to sex and HIV status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2018 Feb 1;18(2):198-206.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kelly H, Chikandiwa A, Vilches LA, Palefsky JM, de Sanjose S, Mayaud P. Association of antiretroviral therapy with anal high-risk human papillomavirus, anal intraepithelial neoplasia, and anal cancer in people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet HIV. 2020 Apr 1;7(4):e262-78.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Glynne-Jones R, Nilsson PJ, Aschele C. Anal cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. EurJSurgOncol40: 1165–1176.

- ↑ Coffey K, Beral V, Green J, Reeves G, Barnes I. Lifestyle and reproductive risk factors associated with anal cancer in women aged over 50 years. British journal of cancer. 2015 Apr;112(9):1568-74.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Morris V, Rao X, Pickering C, Foo WC, Rashid A, Eterovic K, Kim T, Chen K, Wang J, Shaw K, Eng C. Comprehensive genomic profiling of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Molecular Cancer Research. 2017 Nov 1;15(11):1542-50.

- ↑ Zhu X, Jamshed S, Zou J, Azar A, Meng X, Bathini V, Dresser K, Strock C, Yalamarti B, Yang M, Tomaszewicz K. Molecular and immunophenotypic characterization of anal squamous cell carcinoma reveals distinct clinicopathologic groups associated with HPV and TP53 mutation status. Modern Pathology. 2021 May 1;34(5):1017-30.

- ↑ Hoff PM, Coudry R, Moniz CM. Pathology of anal cancer. Surgical Oncology Clinics. 2017 Jan 1;26(1):57-71.

- ↑ Sauter M, Keilholz G, Kranzbühler H, Lombriser N, Prakash M, Vavricka SR, Misselwitz B. Presenting symptoms predict the local staging of anal cancer: a retrospective analysis of 86 patients. BMC gastroenterology. 2016 Dec;16:1-7.

- ↑ Glynne-Jones R, Nilsson PJ, Aschele C, Goh V, Peiffert D, Cervantes A, Arnold D. Anal cancer: ESMO–ESSO–ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2014 Jun 1;111(3):330-9.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Gondal TA, Chaudhary N, Bajwa H, Rauf A, Le D, Ahmed S. Anal Cancer: The Past, Present and Future. Current Oncology. 2023 Mar 11;30(3):3232-50.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Sacomori C, Lorca LA, Martinez-Mardones M, Salas-Ocaranza RI, Reyes-Reyes GP, Pizarro-Hinojosa MN, Plasser-Troncoso J. A randomized clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of pre-and post-surgical pelvic floor physiotherapy for bowel symptoms, pelvic floor function, and quality of life of patients with rectal cancer: CARRET protocol. Trials. 2021 Dec;22(1):1-1.

- ↑ Liang Z, Ding W, Chen W, Wang Z, Du P, Cui L. Therapeutic evaluation of biofeedback therapy in the treatment of anterior resection syndrome after sphincter-saving surgery for rectal cancer. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2016 Sep 1;15(3):e101-7.

- ↑ The Anal Cancer Foundation. Taking Care of You: Tips & Exercises to Restore Your Pelvic Health after Anal Cancer Chemoradiation. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BC4eK10zqGc [last accessed 25/11/2023]