Pelvic Floor Muscle Function and Strength

Original Editor - Kirsten Ryan

Top Contributors - Redisha Jakibanjar, Laura Ritchie, Admin, Mandy Roscher, Kirsten Ryan, Nicole Hills, Alicia Fernandes, Temitope Olowoyeye, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, Scott Buxton and Claire Knott

Introduction[edit | edit source]

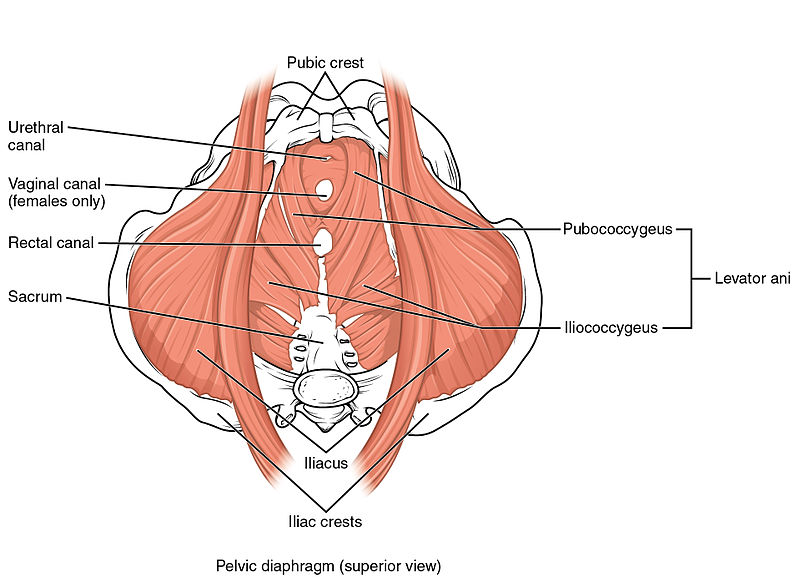

The Pelvic Floor Muscles (PFM) are found in the base of the pelvis. There are superficial muscles as well as the deep levator ani muscles. Changes in their function and strength can contribute to Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and pelvic pain.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Function[edit | edit source]

The pelvic floor muscles provide several important functions such as pelvic organ support, bladder and bowel control, and sexual function. The ability to contract the pelvic floor correctly can be difficult. A proper pelvic floor contraction incorporates both a squeeze and a lift without contraction of other muscles such as the adductors and gluteus.[1][2]

Pelvic Floor Muscle Strength[edit | edit source]

The pelvic floor muscles need to have the ability to maintain a sustained resting tone as well as quick contractions for continence and sexual function as well as the ability to relax to allow for urination and defecation.

Evaluating the strength of the pelvic floor muscles is not as simple as assessing a single maximum voluntary contraction. Factors such as power, endurance, speed of contraction, and ability to relax all need to be evaluated.

Importance of Proper Evaluation of Pelvic Floor Muscle and Function[edit | edit source]

Correct contraction of the pelvic floor cannot be adequately observed externally. People with pelvic floor dysfunction, often struggle to contract the pelvic floor correctly and a thorough examination will allow for an individualized treatment program.

Assessment methods[edit | edit source]

There are various methods that can be used to evaluate the pelvic floor muscles. There is no absolute gold standard for pelvic floor muscle assessment at the moment. Examination of each patient needs to be individualized to what they are comfortable with.

The examination needs to look at the ability of the pelvic floor to contract correctly (squeeze and lift) as well as the strength and endurance of the actual contraction.[1]

External Observation[edit | edit source]

External visual observation of the perineum visualizes what happens during the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles. It is usually the initial step is assessing pelvic floor muscle function.

It is not appropriate to use observation as the only assessment method as the inward movement of the skin may be created by contraction of the superficial perineal muscles and there may be no contraction of the deeper levator ani muscles.[1][2]

Internal Vaginal Digital Palpation[edit | edit source]

Internal digital examination of the vagina is a helpful examination tool[2][3]. It is performed by inserting a finger (or fingers) into the vaginal cavity.

Pelvic floor muscle contraction can be felt and the therapist is looking for both a squeeze and lift.

When doing internal vaginal palpation various aspects of pelvic floor muscle strength need to be examined.

Laycock[3] developed the PERFECT Scheme which is a method of examination of the pelvic floor muscles that looks at

- Power - Modified Oxford Scale)

- Endurance - How long can they hold a maximal voluntary contraction (up to 10sec)

- Repetitions - How many maximal voluntary contractions they hold with a rest between them, up to 10 reps (eg 10 repetitions of a 10-second hold)

- Fast- The number of 1-second maximal voluntary contractions they can perform in a row (up to 10)

- Every Contraction Timed - a reminder to time every contraction

An internal vaginal examination has good intra-rater reliability but only fair inter-rater reliability [4]. This means that follow-up internal examinations by the same practitioner can provide useful information in clinical practice. However, findings between different examiners may not be as accurate

The advantage of an internal vaginal examination is that as well as the muscle strength, anatomical changes, symmetry of a contraction, muscle tone as well as any painful areas can also be examined [4][5]

Ultrasound[edit | edit source]

Real-time trans-abdominal and trans-perineal ultrasound can both be used to assess pelvic floor contractions. Both have been shown to be reliable in assessing the movement of pelvic structures during contraction[6][7].

Transabdominal ultrasound is a non-invasive, valid, and reliable tool that can be used to assess pelvic floor muscle contraction[5]. By placing the ultrasound probe supra-pubically the examiner can evaluate both the squeeze and lift components of the contraction[5]. The strength of muscle contractions cannot be accurately assessed on ultrasound but the ability to contract and endurance can be evaluated accurately.

Real-time ultrasound is helpful as it provides a good visual feedback tool for patients to use as a means of contracting their pelvic floor muscles correctly. Transabdominal ultrasound is also non-invasive so can be used in patients who are not comfortable with an internal examination or where an internal examination is contra-indicated eg children.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging[edit | edit source]

MRI can be used to evaluate pelvic floor dysfunction as well as the ability of the pelvic floor to lift while contracting. Clinically it is very expensive and is not used widely for standard PFM assessment.

Electromyography[edit | edit source]

Surface Electromyography can be used to evaluate the pelvic floor muscles,

PFM activation recorded using transperineal sEMG is only weakly correlated with PFM strength. Results from perineal sEMG should not be interpreted in the context of reporting PFM strength.[4]

Manometers and Dynamometers[edit | edit source]

Manometry and dynamometry are reliable tools that can measure pelvic floor muscle contraction and may be superior to digital palpation as an objective measure of strength.[4]

Evidence-based assessment tools used to evaluate pelvic floor muscles[edit | edit source]

1. Pelvic Floor Questionnaires and Patient Diaries: Patient-reported outcomes, including validated questionnaires and diaries, provide valuable information about symptoms, quality of life, and the impact of pelvic floor dysfunction. Examples include the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ).

2. Perineometry: Perineometry measures pressure changes in the pelvic floor by using a pressure-sensing device. Research has shown its effectiveness in assessing pelvic floor muscle function and identifying dysfunctions such as weakness or hypertonicity.[9]

3. Surface Electromyography (sEMG) Biofeedback: sEMG biofeedback provides real-time feedback on pelvic floor muscle activity, assisting individuals in learning to control and coordinate muscle contractions. Research supports its use in improving pelvic floor muscle function.[10]

4. 3D/4D Transperineal Ultrasound:Advanced ultrasound techniques offer a non-invasive way to visualize and assess pelvic floor anatomy and function. Studies have demonstrated the utility of 3D/4D ultrasound in diagnosing pelvic floor disorders and guiding treatment.[11]

5. Pressure Biofeedback: Pressure biofeedback devices assess pelvic floor muscle strength and coordination. They are used in conjunction with specific exercises to improve muscle function.[12]

When incorporating these tools into clinical practice, it's important to consider the specific needs and conditions of the individual patient. Evidence-based practice involves adapting assessment strategies based on the most current research findings and tailoring interventions accordingly.

Patient Education[edit | edit source]

Educating patients about maintaining pelvic floor health empowers them to make informed lifestyle choices. Here's a comprehensive guide:

1. Pelvic Floor Awareness:[13]

- Educate patients about the location and functions of the pelvic floor muscles.

- Stress the role of these muscles in preventing issues such as incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and sexual dysfunction.

2.Lifestyle Factors:[14]

- Discuss how lifestyle choices, including diet, exercise, and maintaining a healthy weight, can positively impact pelvic floor health.

- Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated to support bladder function.

Tips for Supporting Pelvic Floor Function at Home[edit | edit source]

1. Pelvic Floor Exercises (Kegels):[15]

- Explain the concept of Kegel exercises to strengthen and tone pelvic floor muscles.

- Provide guidance on proper technique: contract and lift the pelvic floor muscles, hold for a few seconds, and then release.

2. Breathing and Relaxation Techniques:[16]

- Teach deep breathing exercises to promote relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles.

- Emphasize the connection between diaphragmatic breathing and pelvic floor relaxation.

3. Maintain a Healthy Posture:[17]

- Educate on the importance of good posture in preventing undue pressure on the pelvic floor.

- Provide tips for maintaining proper alignment during daily activities.

4. Pelvic Floor-Friendly Exercises:[18]

- Recommend exercises that engage core muscles without putting excessive strain on the pelvic floor, such as Pilates or yoga.

- Suggest modifications for high-impact exercises to reduce the risk of pelvic floor issues.

Empowering patients with knowledge about pelvic floor health and providing practical tips for at-home care is integral to preventive healthcare. Encourage individuals to integrate these practices into their daily lives to promote long-term pelvic floor well-being.

Challenges in observing pelvic floor contractions[edit | edit source]

The challenges in accurately observing pelvic floor contractions externally stem from several factors, and numerous studies and clinical findings support the notion that many individuals face difficulties in achieving proper pelvic floor activation.

1. Invisibility of Pelvic Floor Muscles:- The pelvic floor muscles are internal and not visible externally. This inherent invisibility makes it challenging to directly observe the muscles' contractions or assess their function without specialized techniques.

2. Lack of Awareness:- Many individuals lack awareness of their pelvic floor muscles and their role in various functions, such as bladder and bowel control. This lack of awareness can hinder voluntary control and proper contraction.[19]

3. Compensatory Movements:- Individuals often unknowingly engage in compensatory movements, such as contracting the abdominal muscles or squeezing the glutes, instead of isolating the pelvic floor muscles. This can lead to incorrect assessments and treatment plans if not identified.[20]

4. Variability Among Individuals:There is significant variability among individuals in terms of pelvic floor anatomy, muscle tone, and coordination. This diversity makes it challenging to establish a one-size-fits-all approach to pelvic floor assessment.

5. Subjectivity in Self-Reported Data: Relying solely on self-reported data may be subjective and prone to bias. Patients may have difficulty accurately describing their sensations or level of contraction, making it essential to supplement self-reports with objective assessment methods[21].

6.Differentiation of Muscle Groups: Distinguishing between the pelvic floor muscles and adjacent muscle groups can be challenging. Proper evaluation requires precise identification and isolation of the pelvic floor muscles, which may be challenging for both practitioners and patients.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

In summary, assessing pelvic floor muscles (PFM) is crucial for managing dysfunction. Internal vaginal palpation, incorporating the PERFECT Scheme, offers a comprehensive evaluation[22] . Real-time ultrasound provides non-invasive feedback, while manometry and dynamometry offer reliable strength measurement[23] (Dumoulin et al., 2019). Various evidence-based tools contribute to a comprehensive assessment (Bump et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2017).

Patient education, emphasizing PFM functions and exercises, is essential for long-term well-being. Challenges in observing PFM contractions include their invisibility and individual variability[21]. A multifaceted approach, combining subjective and objective methods, is crucial for accurate assessment[17][24], reflecting real-life challenges in clinical practice.

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?

This presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Boyle R, Hay‐Smith EJ, Cody JD, Mørkved S. Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and fecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women: a short version Cochrane review. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2014 Mar;33(3):269-76.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Sartori DV, Gameiro MO, Yamamoto HA, Kawano PR, Guerra R, Padovani CR, Amaro JL. Reliability of pelvic floor muscle strength assessment in healthy continent women. BMC urology. 2015 Dec;15:1-6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Laycock J, Jerwood D. Pelvic floor muscle assessment: the PERFECT scheme. Physiotherapy. 2001 Dec 1;87(12):631-42.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Navarro Brazález B, Torres Lacomba M, de la Villa P, Sanchez Sanchez B, Prieto Gómez V, Asúnsolo del Barco Á, McLean L. The evaluation of pelvic floor muscle strength in women with pelvic floor dysfunction: A reliability and correlation study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2018 Jan;37(1):269-

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Sherburn M, Murphy CA, Carroll S, Allen TJ, Galea MP. Investigation of transabdominal real-time ultrasound to visualise the muscles of the pelvic floor. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2005 Jan 1;51(3):167-70.

- ↑ Thompson JA, O’Sullivan PB, Briffa K, Neumann P. Assessment of pelvic floor movement using transabdominal and transperineal ultrasound. International Urogynecology Journal. 2005 Aug 1;16(4):285-92.

- ↑ Thibault-Gagnon S, Goldfinger C, Pukall C, Chamberlain S, McLean L. Relationships between 3-dimensional transperineal ultrasound imaging and digital intravaginal palpation assessments of the pelvic floor muscles in women with and without provoked vestibulodynia. The journal of sexual medicine. 2018 Mar 1;15(3):346-60.

- ↑ Using Real-Time Ultrasound Imaging to assess Pelvic floor function. Lifecare pilates. Available from:https://youtu.be/nrt7SqoUSZ4

- ↑ Constantinou CE, Omueti DM, Luesley DM. The evaluation of perineometry in the assessment of pelvic floor muscle exercises. Physiotherapy. 1991;77(10):677-81.

- ↑ Dumoulin C, Lemieux MC, Bourbonnais D, Gravel D, Bravo G, Morin M. Physiotherapy for persistent postnatal stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Nov;104(5 Pt 1):504-10.

- ↑ Dietz HP, Shek KL, Chantarasorn V, et al. How important is 3D/4D imaging in the assessment of pelvic floor function? Int Urogynecol J. 2015 Aug;26(8):1125-32.

- ↑ Bø K, Finckenhagen HB. Vaginal palpation of pelvic floor muscle strength: inter-test reproducibility and comparison between palpation and vaginal squeeze pressure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(10):883-7.

- ↑ Hay-Smith, J., Mørkved, S., Fairbrother, K. A., Herbison, G. P., & Bø, K. (2016). Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and fecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women: a short version Cochrane review. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 35(3), 327-333.

- ↑ Bø, K., Hilde, G., & Stær-Jensen, J. (2015). Why do we leak urine during trampoline exercise? The Journal of urology, 193(6), 2006-2011.

- ↑ Dumoulin, C., Hay-Smith, E. J., & Mac Habée-Séguin, G. (2018). Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women: a cochrane systematic review abridged republication. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 54(3), 416-432.

- ↑ Sapsford, R. (2001). Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Manual therapy, 6(1), 3-12.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Smith, M. D., Russell, A., & Hodges, P. W. (2014). Disorders of breathing and continence have a stronger association with back pain than obesity and physical activity. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 60(1), 66-71.

- ↑ Hagen, S., Stark, D., Glazener, C., Dickson, S., Barry, S., Elders, A., ... & Logan, J. (2014). Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383(9919), 796-806.

- ↑ Hay-Smith J, Mørkved S, Fairbrother KA, Herbison GP. Pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD001407.

- ↑ Sapsford R. Compensatory muscle activation patterns in pelvic floor disorders. Man Ther. 2014 Dec;19(6):518-22.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Thompson JA, O'Sullivan PB, Briffa NK, Neumann P. Variability in pelvic floor muscle morphology and function in older women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018 Jan;37(1):334-42.

- ↑ Laycock, J. (2014). PERFECT Scheme - Pelvic Floor Muscle Assessment.

- ↑ Dumoulin, C., Cacciari, L. P., Hay-Smith, E. J. C., Glazener, C. M. A., Jenkinson, D., & Hagen, S. (2019). Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2019(12),

- ↑ Bump, R. C., Mattiasson, A., Bo, K., Brubaker, L. P., DeLancey, J. O. L., Klarskov, P., ... & Smith, A. R. B. (2020). The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal, 31(1), 111–153.