Thoracic Disc Syndrome

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (17/04/2020)

Original Editor - Sarah Harnie

Top Contributors - Sarah Harnie, Maarten Wuijts, Arno Vrambout, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Marleen Moll, Rachael Lowe, 127.0.0.1, Bouzarpour Faryân, Claire Knott, Abbey Wright, Admin, Evan Thomas and WikiSysop

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

'Thoracic syndrome’ is an umbrella term for all pathological clinical manifestations due to functional (physiopathological) disturbances and degenerative changes of the thoracic motion segments. Essentially, we distinguish three kinds of degenerative diseases of the thoracic spine:

- Benign spondylosis and osteochondrosis in the ventral portion of the thoracic motion segments

- disc prolapse into the epidural space with and without clinical signs of spinal cord compression

- Structural and functional disturbances of the intervertebral and costovertebral joints.

Disc disease in the thoracic spine is far less common than in lumbar and cervical regions, it only accounts for 2% of all cases of disc disease and tends to be less serious than disc disease elsewhere in the spine.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

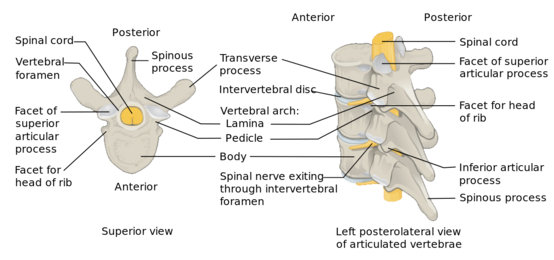

The twelve thoracic discs become broader and higher caudally. In terms of ratio of width to height, they are more flat than the cervical and lumbar discs. The thoracic spinal canal is quite narrow (most so from T4-T9) with a thin epidural space between the spinal cord and surrounding bone or disc.

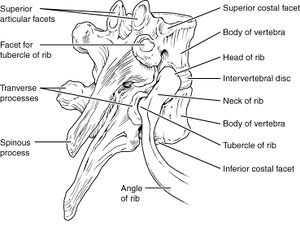

Besides the intervertebral joints, the thoracic spine also contains the costotransverse joints which indent the lower portion of the intervertebral foramina. Because the thoracic foramina are much wider, bony narrowing such as is seen in the cervical spine, is hardly ever seen here.[1]

The thoracic spine is a relatively rigid part of the spine, compared to the cervical and lumbar parts. Its stability is the direct result of the rib cage. Each rib head between T2 and T10 has two facets that articulate with their respective vertebral body and one more cephalic - meaning that the head of the T7 rib articulates with the T6 and T7 bodies. The heads of T1, T11 and T12 ribs only articulate with their similarly numbered vertebral bodies[2].

Because the facets of the T1-T10 vertebral bodies are oriented vertically (with slight medial angulation in the coronal plane) there is significant stability during flexion and extension, while allowing greater movement in lateral bending and rotation[2]. The active movements the average individual can carry out in the thoracic spine are as follows:

• Forward flexion (20° to 45°)

• Extension (25° to 45°)

• Side flexion, left and right (20° to 40°)

• Rotation, left and right (35° to 50°)[3]

The curvature of the thoracic spine is convex, which places the ventral portion of the motion segments under greater stress with high intradiscal pressure. This is different from the cervical or lumbar spine, where an axial compressive force can be borne by the intervertebral joints and interlaminar soft tissue.[1]

Between each vertebral body lies the intervertebral disc. These are composed of two materials: the outer hard fibrous ring (annulus fibrosis) and an inner soft gelatinous core (nucleus pulposus). The intervertebral discs absorb shock and allow flexibility of the vertebral column. As the body ages, the integrity of the intervertebral disc declines and can cause the inner core of the disc to protrude through the outer layer, leading to possible compression of the nerve roots or the spinal cord - giving rise to radicular or myelopathic symptoms.[4]

Justin G. R. Fletcher et.al concluded that all dimensions (anterior disc height, posterior disc height, anteroposterior disc dimension and transverse disc dimension) of the thoracic disc were greater in men than in women, except the middle disc height. The researchers explain this difference with a scaling effect because the differences in disc and vertebral body heights (6-9%) were proportionally similar to their mean difference in stature (7%). The lower thoracic spine has a larger range of flexion and extension, which is why the disc height is greater in the more caudal discs of the thoracic spine. Anteroposterior and transverse dimensions of the thoracic intervertebral discs increase caudally because these discs need to support a greater compressive load. The greater axial cross-sectional area reduces compressive stress in these discs.[5]

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Because the thoracic discs and vertebral bodies must carry the entire burden, we find more vertebral compression fractures and protrusions of disc tissue through the vertebral body end plates into the spongiosa. The pressure also leads to premature regressive changes (particularly in the middle and lower thoracic section) and can involve extensive spondylosis and osteochondrosis. However, these changes are usually asymptomatic and only noticed incidentally on radiological studies.[6]

Why clinically significant thoracic disc disease is less common, has essentially two causes:

- As opposed to the cervical or lumbar spine, the intervertebral foramina of the thoracic spine are located at the level of the body, as opposed to directly behind the discs.

- There is relatively little movement in the thoracic motion segments, so the anatomical relationship of neural structures to their surroundings remains constant.[1]

Thoracic disc herniation is rare and asymptomatic in 70% of the cases[7], making up only 0.5% to 4.5% of all disc ruptures[8] and 0.15%-1.8% of surgically treated herniations.

Most patients (80%) that present with problems are between 30-40 years old. Han & Jang demonstrated a relatively even distribution in prevalence across age groups: higher in male participants (8.0%) than in female participants, and more frequent in patients with lumbar surgical lesions (8.2%) than without surgical lesions.[9]

Thoracic disc lesions are primarily degenerative of nature and affect mostly the lower part of the thoracic spine.[2] Three quarters of incidence occurs below T8, with T11-T12 being most common.[8][9] The exact cause of disc degeneration is believed to be multifactorial, factors that can attribute include:[10]

- Trauma

- Metabolic abnormalities

- Genetic predisposition

- Vascular problems, and

- Infections

As mentioned above, symptomatic thoracic disc degeneration is clinically rare. The role of injury in patients with thoracic disc herniation is unclear, with contradicting numbers in different articles. A history of trauma may be present in younger individuals who develop thoracic pain. Literature describes a few cases of thoracic disc herniation in top athletes, such as professional baseball pitchers.[10]

It is worth noting that in acquired deformities of the spine (such as scoliosis or Scheuermann disease) develop gradually which allow the nerve roots to adapt to the situation thereby not necessarily causing thoracic syndrome.[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

In all thoracic pain, extensive anamnesis is important, particularly in patients with a history of carcinomas. General matters such as weight loss, (chronic) coughing, past trauma, thoracic surgery and infections must also be explored.

Degenerative thoracic syndromes can be classified as local, radicular (intercostal neuralgia) or pseudoradicular. Red flags one should be aware of are:

- Myelopathy

- Gait disturbance

- Paralysis

- Cardiovascular disturbances

- History of: - Trauma - Tumor - Infection - Constitutional symptoms (feeling ill) - Weight loss - Laboratory abnormalities

Initially, the most common thoracic pain occurs in the midline area. This can be unilateral or bilateral pain and is dependent on the location and significance of the herniation.[6] The patient might describe a band-like discomfort in a dermatomal distribution in the case of radicular pain. Axial pain is usually described as mild to moderate in intensity, localised in the middle to lower thoracic region. A radiating component may be present, referred to the middle to lower lumbar spine[2].

In the case of thoracic prolapse, the patient might give a history of axial compression of the trunk (e.g. bending forward and lifting a heavy object). The clinical presentation of symptomatic thoracic disc herniation can vary widely and patients may present with either radicular and/ or myelopathic pain. This depends on if the herniated disc compresses the nerve roots or spinal cord itself. The pain worsens when the patients coughs or increases the intra-abdominal pressure[1].

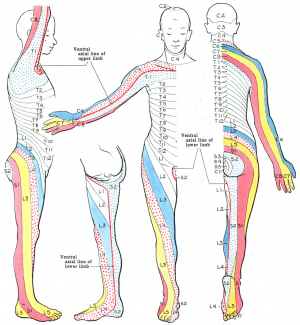

Patients with radicular pain will have pain following the dermatomal distribution, for example pain will radiate to:

- Medial forearm (T1)

- The axilla (T2)

- Nipple area (T4)

- Umbilicus (T10)

- Just above the inguinal ligaments (T12)

In upper thoracic and lateral disc herniations, radicular pain is more common and often reported in combination with some amount of axial pain. Second most commonly reported are sensory changes (e.g. parenthesias, dysesthesia) below the level of the lesion. Other symptoms include bladder and bowel dysfunction (15-20% of patients), hyperreflexia and gait impairment.[1][2]

The presentation of myelopathic pain is worrisome. The patient might complain of muscle weakness; the most common lower-extremity manifestation of thoracic disc herniation. Signs of myelopathy that indicate thoracic cord compression are:

- Positive Babinsky sign

- Sustained clonus

- Widebased gait

- Spasticity

Herniation of a thoracic disc is an uncommon cause of chest wall pain, but it has been documented in athletes.[10] A band-like pain in thoracic dermatomes is usually a symptom of intercostal neuralgia.[1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Because thoracic disc syndroms are relatively rare, symptoms in this area will more likely arouse suspicion of disease of the internal organs or a primary disorder of the nervous system. It is important that the patient is examined thoroughly to rule out all other causes for symptoms.[1][2][6]

Rule out conditions that can cause thoracic pain such as:

- Diabetes and shingles

- Other mechanical issues such as oblique muscle pain, rib fracture, fracture of the facet joints and clavicle

- Malignancies, like neurofibroma

- Herpes zoster (can cause segmentally radiating pain with postherpetic neuralgia)

- Costotransverse joint syndrome due to inflammatory changes or arthrosis

- Infections, tumors and dilated arteries of the chest wall

- Referred pain from the organs (zones of Head)

- Tietze syndrome

- Scheuermann kyphosis

Pain referred around the chest wall tends to be costovertebral in origin.[3]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

The precise location of the pain and its radiation has to be explored. The character of the pain and provoking conditions (static and dynamic load) can provide information about the aetiology and nature of the pain (neuropathic versus nociceptive).

Physical examination should include assessment of sensation with pinprick and touch in the upper extremity, thorax, and abdomen in the dermatomal regions mentioned above to check for radiculopathy and also in the lower extremity to check for myelopathy. Also, for the lower extremity, proprioception and reflexes and tonus should be evaluated. Start your examination with:

- History

- Observation (standing) Examination

- Active movements (standing or sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right) - Combined movements (if necessary) - Repetitive movements (if necessary) - Sustained postures (if necessary)

- Passive movements (sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right) - Resisted isometric movements (sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right)

- Functional assessment

- Special tests (sitting) - Adson’s test - Costoclavicular maneuver - Hyperabduction (EAST) test - Roos test - Slump test

- Reflexes and cutaneous distribution (sitting)[11][12] - Reflex testing - Sensation scan

- Special tests (prone lying) - Joint play movements (prone lying) - Posteroanterior central vertebral pressure (PACVP) - Posteroanterior unilateral vertebral pressure (PAUVP) - Transverse vertebral pressure (TVP) - Rib springing - Palpation (prone lying)

- Special tests (supine lying) - First rib mobility - Rib springing - Upper limb neurodynamic (tension) test 4 (ULNT4) - Palpation (supine lying) - Federung test (segmental translation of the thoracic vertebrea)

- Sensitivity of the thorax and stomach

After any assessment, the patient should be warned of the possibility of exacerbation of symptoms as a result of assessment.[3]

Additional diagnostics[edit | edit source]

There is a limited correlation between radiographical findings and clinical symptoms in non-specific thoracic spine pain.

MRI is the imaging method most used to arrive at a diagnosis[12]. However, it should be noted that there is a potential for spinal incidental findings.[13][14] Studies that investigated the rate of abnormal findings in the asymptomatic patient suggest that although MRI is highly sensitive, it is not a specific imaging modality.[15] MRI is superior to CT to demonstrate degenerative changes, disc protrusion and nerve root compression. In addition, intra- and extradural tumours can easily be seen on MRI.[7]

Additional imaging is indicated in the case of:

- Trauma (with or without osteoporosis)

- Suspicion of malignancy, particularly in patients with a history of malignancy and acute thoracic pain

- In case of neurological deficits

- Suspicion of pathology in the chest wall and/ or presence of pulmonary complaints

- Suspicion or presence of visceral pathology

Psycho-cognitive diagnostics[edit | edit source]

- Quality of life questionnaire

- VAS-pain scale

- Pain Catastrophizing Scale

- Fear-avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire

- Functional Rating Index

- Patient Specific Functional Scale

- Tampa Scale for kinesiophobia

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Passive movements of the thoracic spine and normal end feel:[3]

• Forward flexion (tissue stretch)

• Extension (tissue stretch)

• Side flexion, left and right (tissue stretch)

• Rotation, left and right (tissue stretch)

Loss of sensitivity indicates whether or not the pain is neuropathic. Pain provocation by performing passive movements, in particular rotation, forward flexion, backward flexion and lateral flexion can indicate a spinal aetiology.

Weakness, inflexibility and/or myofascial pain in the thoracic spine as well as the abdominal and hip musculature can be related to thoracic discogenic syndrome.[6] In the case of purely discogenic pain or thoracic radiculopathy, the upper extremity reflexes as well as the patellar and Achilles reflexes should be normal. If there is weakness associated with hyperactive patellar or achilles reflexes or spasticity, myelopathy is indicated. [11]

Paralysis of the lower abdominal muscles while the upper abdominal muscles preserve their strength can be a sign of leasion at T9/T10. The lesion can cause a Beevor sign, where the umbilicus makes an upward movement when the abdominal wall contracts. Observing if the movement of the rectus abdominis is asymmetric.

Sensory symptoms can be present if the patient has a thoracic disc herniation. It can cause altered sensation to light touch or pinprick along a dermatomal pattern. Cord compression and myelopathy should be strongly considered if a sensory level is established such that sensation is consistently altered below a specific dermatome. [16]

Provocative manoeuvres such as the Spurling manoeuvre (cervical radiculopathy) and the Straight-Leg Raise test or the Slump Test (lumbosacral radiculopathy) may exclude a thoracic disc syndrome.[1][11][12]

Thoracic intervertebral disc degeneration on MRI is shown by a decrease in signal intensity with or without loss of disc height. A normal, healthy disc displays a high intensity signal. Disc degeneration can be detected by a reduced signal intensity due to loss of water from the nucleus pulposus. [1]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Most patients with symptomatic thoracic disc disease will respond favourably to non-operative management.

If there is no surgery performed, a short period of rest is recommended (one or two days). After this short period, the patient should resume his activities. The patient can take pain medications. If the pain is severe, narcotic pain medication can be described for a short period. Also anti-inflammatory agents (NSAID’s) can be described to help reduce inflammation around the herniated disc.

If the patient has severe pain, epidural steroid injection (ESI) can become an option. Surgery is indicated for the rare patient with an acute thoracic disc herniation with progressive neurologic deficit (i.e., signs or symptoms of thoracic spinal cord myelopathy).

Only 5% of all disc herniations are symptomatic thoracic disc herniations. From this number we can conclude that it is an uncommon problem. Till today there is little know about the natural history of this disease which makes the indications for surgery unclear. Even though, severe and progressive myelopathy are considered as absolute indications for surgery. [12]

Earlier, the number one approach to treat thoracic disc herniations non-conservatively, was laminectomy. The outcomes of this surgery method were disappointing because of high complication rates and unsatisfactory operative results. Nowadays is this technique not in use anymore. [12]

Since then there have been newer approaches developed to treat thoracic disc herniations, such as: the transpedicular approach and the transfacet pedicle-sparing approach. These two methods of operation are relatively safe, especially when the disc herniation is situated laterally.

However, when a disc is herniated centrally, these techniques can cause high complication rates, mainly because the spinal cord has to be mechanically manipulated to guarantee visibility during the surgery. This process can produce direct mechanical injury to the spinal cord and it can possibly interfere with the blood supply of the cord. [12]

For the treatment of patients with central thoracic disc herniation, there have been safer and more suitable approaches developed, such as costotransversectomy, a lateral extracavitary (posterolateral approach) or a classic transthoracic (anterolateral) approach.

These techniques make sure there is direct access and visibility to the disc during the operation. Disadvantages can be the more extensive nature of these approaches and in the case of transthoracic techniques there can be a chance of developing pulmonary and mediastinal complications. To avoid these complications, thoracoscopic techniques have been invented, which minimize the invasive nature of the proces. The only downside of this process is that the learning curve to acquire sufficient experience in the practice of these techniques is very long and it is not easy to achieve because of the small number of patients with symptomatic thoracic disc herniation. [12]

From the study of Coppes Et.al we can conclude that the posterior transdural approach to treat symptomatic thoracic disc herniation seems like a promising procedure to remove centrally herniated thoracic intervertebral discs. [12]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Because Individuals with congenital or developmental deformities of the spine such as scoliosis or kyphosis may be more likely to develop thoracic disc degeneration, exercise therapy in improving postural hyperkyphosis is recommended.

The intervention should be a multimodal, kyphosis specific exercise program. It should target multiple musculoskeletal impairments known to be associated with hyperkyphosis, including spinal extensor muscle weakness, decreased spinal mobility, and poor postural alignment.[1]

This Physical therapy should than involve:

- Hyperextension strengthening [17]; [1] [5]

- Postural training [17] ; [1]

- Body mechanics education [17]

- McKenzie technique

- Maitland technique

- Stretching of the M. Pectoralis Major ([5])

- Mobilisation [5]

- Massage

- Passive mobilisation [5]

Hyperextension strengthening

Training of the muscles used for hyperextention. This is done to prevent the hyperkyphosis, most patients with thoracic disc problems are in a position of hyperkyphosis. This is a big problem especially in the 21th century, because of the portables and tablets. which is the cause of most thoracic disc problems.

Strengthening of the thoracal extensor muscles can be achieved by following exercises:

Bow and arrow on the side [1]

With this exercise it is important to give the following instructions:

- The upper back and abdominal muscles should be working at all times.

- The legs should not be moving and should be in a 90° angle in the hip and in the knee to make sure that the pelvis stays in position.

Foto 6: bow and arrow exercise nicksportphysio.com

Pointer dog [1]

- With this exercise it is important to give the following instructions:

- The upper back and abdominal muscles should be working at all times as well as the pelvic floor.

- Don’t raise your leg and arms to high (max horizontal)

Foto 7: 3 Bird-Dog Exercise Variations www.builtlean.com

Superman[1]

- With this exercise it is important to give the following instructions:

- The upper back and abdominal muscles should be working at all times

- Start with lifting your legs slightly of the floor than lift your torso of the floor

Foto 8: (Katzman WB, Vittinghoff E, Kado DM, Schafer AL, Wong SS, Gladin A, Lane NE.

Study of Hyperkyphosis, Exercise and Function (SHEAF) Protocol of a Randomized

Controlled Trial of Multimodal Spine-Strengthening Exercise in Older Adults With

Hyperkyphosis. Phys Ther. 2016 Mar;96(3):371-81 - LoE 1B)

Occiput to wall [5]

Stretching the Extensor Muscles and strengthening the Anterior Neck Flexors: The patient stands with his back against the wall and retracts the chin. There will be an upper cervical spine flexion and lower cervical spine extension. Hold this position for 15 seconds. [5]

Postural training

The training of all the postural muscles is important to assure the stability of the spine, the muscles should be trained for long periods of time to simulate the use in the daily life activities such as standing for a long period of time. ([7] [1])

Training of the postural muscles can be achieved by following exercise:

Single leg stance [1]

With this exercise it is important to give the following instructions:

- The upper back and abdominal muscles should be working at all times as well as the pelvic floor.

- Roll shoulder blades backwards

“Lengthen” your neck

Don’t raise your leg to high (+- 10cm of the floor)

Foto 9: ( Katzman WB, Vittinghoff E, Kado DM, Schafer AL, Wong SS, Gladin A, Lane NE.

Study of Hyperkyphosis, Exercise and Function (SHEAF) Protocol of a Randomized

Controlled Trial of Multimodal Spine-Strengthening Exercise in Older Adults With

Hyperkyphosis. Phys Ther. 2016 Mar;96(3):371-81 - LoE 1B)

Body mechanics education

It is is important that the patiënt understands his problem and the cause of his problem. In the particular case of thoracic disc herniation it is important that the patiënt realises that being in a position of hyperkyphosis will increase his symptoms. [7]

Foto 3 (41) Encyclopedia of Sportsmedicine p257 Lyle J., Micheli M.D. (LoE: 5)

https://www.ugbodybuilding.com/threads/3572-Lumbar-Disc-Herniation

disc bulging, difference between the bend forward position and the bend backward position. (This is a photo of what goes on in the lumbar spine but the same occurs in the thoracic spine) [7]

McKenzie technique

This technique is used to re centralise the bulging disc. But also to ‘centralise’ complaints from peripheral (first days) to thoracic region (after 10 days)

Foto 4 (42) Athletic Training and Sports Medicine; Schrijver: Robert C. Schenck; Editor: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 1999 (LoE: 5)

Maitland technique

The maitland technique uses specific methods of oscillation or sustained holds to eliminate reproducible signs of pain.

Foto 5

Athletic Training and Sports Medicine; Schrijver: Robert C. Schenck; Editor: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 1999 (LoE: 5)

Stretching M. pectoralis major and M. latissimus dorsi

Manual therapy and exercise therapy program improving postural hyperkyphosis:

Stretching the Pectoralis Major Muscle: While facing a corner, the patient places his hands on the wall at shoulder level. Than the patient moves forward, closer to the wall, to stretch the anterior chest. Hold this position for 15 seconds. [5]

Stretching the Latissimus Dorsi Muscle: Patient lay in supine position with knees and hips flexed. Arms are in 90-90 position. Then the patient performs a posterior pelvic tilt while raising the arms overhead as far as possible without losing floor contact. Hold this position for 15 seconds.

Massage

Massage: wringing and skin rolling massage to the back extensor muscles for 10 minutes

Passive mobilisation

Apply downward pressure toward thoracic extension.

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

• H. Yoshihara, Surgical Treatment for Thoracic Disc Herniation, An Update. Spine 2014;39:E406–E412.

• E.M.J. Cornips et al., Thoracic disc herniation and acute myelopathy: clinical presentation, neuroimaging findings, surgical considerations, and outcome. J Neurosurg Spine 14:520–528, 2011

• George A Koumantakis et al; Trunk Muscle Stabilization Training Plus General Exercise Versus General Exercise Only: Randomized Controlled Trial of Patients With Recurrent Low Back Pain; PHYS THER. 2005; 85:209-225.

Resources[edit | edit source]

• http://www.spineuniverse.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/gallery-large/wysiwyg_imageupload/3998/2015/04/02/DDD_labeled.jpg (foto disc deseases)

• http://keckmedicine.adam.com/graphics/images/en/19469.jpg (disc anatomy Adam)

• Video link: explanation thoracic herniation disc : http://www.spine-health.com/video/thoracic-herniated-disc-video

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the <a href="Template:Case Study">case study template</a>)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5131583/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26156777?log$=activity

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19404165

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

The term ‘thoracic syndrome’ refers to all pathological clinical manifestations due to functional (physiopathological) disturbances and degenerative changes of the thoracic motion segments.[1] Due to the rarity of this subject, little importance is attached to it in the literature. [7]

Several articles suggest an incidence between 0.2% and 5.0% of all intervertebral disc herniations. It should also be more common in men. [17]

Mostly these disc disorders do not cause any symptoms. If, nevertheless, symptoms are extant, pain is the most common.(25) Other symptoms are sensory disturbances, referred pain, weakness in the abdominal and intercostal muscles, paresthesias, weakness of the lower extremities and bladder symptoms. [11][12]([1][17]([7]

One of the main problems in the treatment of thoracic disc herniation has been the lack of accuracy of diagnostic tests. Disc herniation can be revealed by MRI but there aren’t really specific physical test to include this disease. Literature show that musculoskeletal, reflexes, sensory aspects, strength and provocative maneuvers should be tested.([11][12][1]

From medical research we can conclude, based on the study of Coppes. et.al , that the posterior transdural approach seems like a promising procedure to remove centrally herniated discs in patients with symptomatic throacic disc herniation. [16]

Thoracic disc protrusions can be reduced by manipulation in 3 to 5 sessions.

Physical therapy should involve hyperextension strengthening [12], postural training [12] body mechanics education [12], McKenzie technique [17] and Maitland technique [17].

Case Studies

In the case study of Bin Yue et.al they present two adult patients with thoracic intervertebral disc calcification and herniation. The purpose of this study was to report two cases of patients with acute paraplegia caused by a calcified thoracic disc prolapse and to discuss the clinical diagnosis and surgical treatment of this problem. [18]

Case 1

In the first case, the patient was a woman, 57-years old with back pain already for 40 days. She experienced numbness in her lower extremity, bilateral and weakness for 20 days, bowel or bladder incontinence for 5 days. The findings of physical examination were: a lesser sensation below T11 level, bilateral lower extremity paraplegia with muscle force level zero, diffuse hyperreflexia(patellar jerk and Achilles tendon reflex for +++) and positive Babinski signs. CT imaging showed calcification of the nucleus pulposus with posterior central herniation within the disc space at level T11-T12. MRI showed a serious level of compression of the spinal cord at the disc of the segment T11-T12. After the diagnosis: calcified thoracic intervertebral disc with herniation, the patient underwent discectomy done with a posterior transfacet approach, which was followed by interbody fusion with instrumentation. The surgeon removed the calcified parts of the disc.

The results of the pathological examination of the removed parts was: degenerative fibrocartilage and calcium deposition. After a 2-year follow-up the patient did not show any important functional change in the postoperative period (such as muscle force, hyperreflexia, Babinksi signs). [18]

Case 2

The second patient of this study was a 53-year old man with back pain for 2 months, paraplegia of the lower extremity bilateral and bowel or bladder incontinence for 15 days. The main complaint of the patient was back pain. The findings of physical examination were: paresis of the lower extremity bilateral below the level T10, paraplegia of the lower extremity bilateral with muscle force level zero and diffuse hyperreflexia(patellar jerk and Achilles tendon reflex for +++) with positive Babinski signs. CT imaging showed some high-density mass at the disc of the level T10-T11. MRI results showed a serious degree of spinal cord compression with a hyperintense central core and surrounding hypointense area at the intervertebral disc at level T10-T11. These findings led to the diagnosis: intervertebral disc calcification and protrusion. The surgical method of getting rid of the calcification was in this case also disectomy, through transversoarthropediculecttomy via bilateral posterolateral approach and interbody fusion with instrumentation. The researchers have found similar results as they have found in case 1: calcium deposition in the disc which was like ‘semisolid toothpaste’. This patient was followed-up 6 months and they have established full recovery (sensation, muscle force, hyperreflexia, and Babinski signs). [18]

Researchers of this study found that if decompression surgery would not have been performed, spinal cord compression would have progressed further in these two patients which would have inevitably caused spinal cord injury. The research team therefore suggests to carry out decompression surgery as soon as possible for patients with early spinal myelopathy or paraplegia caused by a calcified protruded disc. [18]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 Juergen Kraemer, 2009, Intervertebral Disk Diseases: Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prophylaxis , Thieme , Stuttgart, 375p. (LoE 5)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Vanichkachorn, Jed S., and Alexander R. Vaccaro. "Thoracic disk disease: diagnosis and treatment." JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 8.3 (2000): 159-169.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Magee, D. J. (2008). Orthopedic physical assessment. St. Louis, Mo: Saunders Elsevier. Print.

- ↑ Amelot A, Mazel C. The Intervertebral Disc: Physiology and Pathology of a Brittle Joint. World Neurosurg. 2018 Dec;120:265-273.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Justin G. R. Fletcher et.al; CT morphometry of adult thoracic intervertebral discs; European Spine Journal; 2015; 24: 2321-2329; LoE: 5

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Fogwe, Delvise T., Hassam Zulfiqar, and Fassil B. Mesfin. "Thoracic Discogenic Syndrome." StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, 2019.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Ozturk C, et all. Far lateral thoracic disc herniation presenting with flank pain. The Spine Journal. 2006;6:201-203 LoE 3B

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Göçmen S, Çolak A, Mutlu B, Asan A. Is back pain a diagnostic problem in clinical practices? A rare case report. Agri. 2015;27(3):163-5.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Han, Seok, and Il-Tae Jang. "Prevalence and distribution of incidental thoracic disc herniation, and thoracic hypertrophied ligamentum flavum in patients with back or leg pain: a magnetic resonance imaging-based cross-sectional study." World neurosurgery 120 (2018): e517-e524.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Kato K, Yabuki S, Otani K, Nikaido T, Otoshi K, Watanabe K, Kikuchi S, Konno S. Unusual chest wall pain caused by thoracic disc herniation in a professional baseball pitcher. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2016 Jun 08;62(1):64-7.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Whitmore R.G, et all. A patient with thoracic intradural disc herniation. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 18. 2011:1730-1732 LoE:3B

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 Deitch K, et all. T2-3 Thoracic disc herniation with myelopathy. The journal of Emergency Medicine.2009;36(2):138-140 LoE 3B

- ↑ Ramadorai, Uma E., Justin M. Hire, and John G. DeVine. "Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine in children: Spinal incidental findings in pediatric patients." Global spine journal 4.4 (2014): 223-228

- ↑ Wu, Pang Hung, Hyeun Sung Kim, and Il-Tae Jang. "Intervertebral Disc Diseases PART 2: A Review of the Current Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies for Intervertebral Disc Disease." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21.6 (2020): 2135.

- ↑ Baker, Alexander DL. "Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation." Classic papers in orthopaedics. Springer, London, 2014. 245-247.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Malanga G, et all. Thoracic Discogenic Pain Syndrome. [1] recieved 1 may 2016

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 Jed S. Vanichkachorn, MD and Alexander R. Vaccaro, MD. Thoracic Disk Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2000. 8:159-169.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 27 Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. Diagnosis and conservative management of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2008 Mar. 17(3):327-35. . LoE: 1B