Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

Original Editor - Rachael Lowe

Top Contributors - Pacifique Dusabeyezu, Alyssa Aquino, Rachael Lowe, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Kim Jackson, Admin, Rucha Gadgil, Shaimaa Eldib, Laura Ritchie, Faye Underwood, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, 127.0.0.1, Audrey Brown, Evan Thomas, Naomi O'Reilly and Michelle Lee

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a genetic condition which affects the muscles, causing muscle weakness. It is a serious condition which starts in early childhood. The muscle weakness is not noticeable at birth, even though the child is born with the gene which causes it. The weakness develops gradually, usually noticeable by the age of three. Symptoms are mild at first but become more severe as the child gets older.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the most common type, is one of more than 20 muscular dystrophies. The incidence of DMD globally is every 1/3500 male births[1] That means that there is approximately 2400 individuals living with DMD in the UK alone[2].

| Type | Prevalence | Common Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | 1 in 3,500 | • Difficulty walking, running or jumping

• Difficulty standing up • Learn to speak later than usual • Unable to climb stairs without support • Can have behavioural or learning disabilities |

| Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy | 1 in 7,500 | • Sleeping with eyes slightly open

• Cannot squeeze eyes shut tightly • Cannot purse their lips |

| Myotonic Dystrophy | 1 in 8000 | • Muscle stiffness

• Clouding of the lens in the eye • Excessive sleeping or tiredness • Swallowing difficulties • Behavioural and learning disabilities • Slow and irregular heartbeat |

| Becker Muscular Dystrophy | Varies;

1 in 18,000 – 1 in 31, 000 |

• Learn to walk later

• Experience muscle cramps when exercising |

| Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy | Estimated to be in a range of 1 in 14,500 – 1 in 123,000 | • Muscle weakness in hips, thighs and arms

• Loss of muscle mass in these same areas • Back pain • Heart palpitations / irregular heartbeats |

| Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy | 1-9 in 100,000 | • Does not usually appear until age 50-60

• Dropped eyelids • Trouble swallowing • Gradual restriction of eye movement • Limb weakness, especially around shoulders and hips |

| Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy | 1 in 100,000 | • Develop symptoms in childhood and adolescence

• Muscle weakness • Trouble on stairs • Tendency to trip • Slow, irregular heartbeat |

All types of muscular dystrophies are caused by faults in genes (the units of inheritance that parents pass on to their children) which result in progressive muscle weakness due to muscle cells breaking down and gradually becoming lost. The Duchenne type dystrophy is an X-linked genetic disorder affecting primarily boys (with extremely rare exceptions) and a problem in this gene is known to result in a defect in a single important protein in muscle fibres called dystrophin. It is named after Dr Duchenne de Boulogne who worked in Paris in the mid-19th century who was one of the first people to study the muscular dystrophies.

Clinically relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

Dystrophin is responsible for connecting the cytoskeleton of each muscle fiber to the underlying basal lamina. The absence of dystrophin stops calcium entering the cell membrane affecting the signalling of the cell, water enters the mitochondria causing the cell the burst. In a complex cascading process that involves several pathways, increased oxidative stress within the cell damages the sarcolemma resulting in the death of the cell, and muscle fibers undergo necrosis and are replaced with connective tissue.

Small amounts of dystrophin are also made in nerve cells (neurons) in specific parts of the brain, including the hippocampus. The hippocampus is the part of the brain involved in learning and memory, as well as emotions. The non-progressive memory and learning problems, as well as social behavioural problems, in some boys with DMD, are most likely linked to loss of dystrophin in the neurons of the hippocampus and other parts of the brain where dystrophin is normally produced in small amounts, however, studies are being carried out to find out why only a small no. of DMD individuals are affected by this.[9]

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

The cause is a mutation in the gene that encodes the 427-kDa cytoskeletal protein dystrophin which affects the muscles. People with DMD have a shortage of dystrophin in their muscles. The lack of dystrophin leads to muscle fibre damage and a gradual weakening of the muscles.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

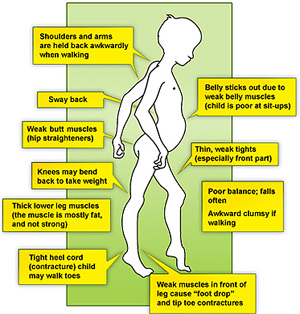

The muscle weakness is mainly in the 'proximal' muscles, which are those near the trunk of the body, around the hips and the shoulders. Weakness typically starts proximally in the lower extremities, then moves distally. Weakness in the upper extremities tends to appear later[1]. This means that fine movements, such as those using the hands and fingers, are less affected than movements like walking.

The symptoms usually start around age 1-3 years, and may include:

- Difficulty with walking, running, jumping and climbing stairs. Walking may look different with a 'waddling' type of walk. The boy may be late in starting to walk (although many children without DMD also walk late).

- When you pick the child up, you may feel as if he 'slips through your hands', due to the looseness of the muscles around the shoulder.

- Toe-walking, In this gait pattern, children walk on their toes with feet apart to help maintain balance, with an increased curve in the lower back[10].

- Frequent falls

- The calf muscles may look bulky, although they are not strong.

- As he gets older, the child may use his hands to help him get up, looking as if he is 'climbing up his legs'. This is called 'Gower's sign'.

- Some boys with DMD also have a learning difficulty. Usually, this is not severe.

- Sometimes, a delay in development may be the first sign of DMD. The child's speech development may also be delayed. Therefore, a boy whose development is delayed may be offered a screening test for DMD. However, DMD is only one of the possible causes of developmental delay - there are many other causes not related to DMD.

- Contractures are a classic finding in DMD[11]. It develops when tissues, such as muscle fibers, which are normally stretchy are replaced by hardened, non-stretchy tissue[11]. They are seen as a major cause of disability[12]. They prevent normal movement, and, for children with DMD, occur often in the legs, especially the calf and muscles around the hip

- Progressive enlargement of heart

| [13] | [14] [15] |

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis may be suspected because of the child's symptoms (above). When looking for signs of DMD, it is important to watch the child running and getting up from the floor - the muscle weakness is more noticeable during these activities.

Gower’s Sign is a very common physical finding for boys with Duchenne’s[16]. It involves using their hands to ‘climb’ up their legs in order to stand up[16]. It is due to a weakness in the child’s hip muscles[16].

Tests are needed before DMD can be diagnosed. The first step in making the diagnosis is a blood test. This tests for creatine kinase. Children with DMD always have a very high level of creatine kinase (about 10-100 times normal). Therefore if a child's creatine kinase level is normal, then DMD is ruled out. If the creatine kinase level is high, further tests are needed to see whether this is due to DMD or to some other condition.

The next step in diagnosing DMD involves either a muscle biopsy and/or genetic tests:

- A muscle biopsy involves taking a small sample of a muscle, under local anaesthetic. The sample is examined under a microscope using special techniques to look at the muscle fibres and the dystrophin protein.

- Genetic tests are done using a blood sample. The DNA in the blood is tested to look at the dystrophin gene. This test can diagnose most cases of DMD.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures for a DMD individual vary according to the progression of the disease.

Outcome measures to quantify disease progression, including:

- 6‐minute walking test

- North Star ambulatory assessment scale,

- Time taken to climb four steps

- Time taken to rise from the floor

- Performance of upper limb.

One of the limitations of these measures is the fact they target either ambulant or non‐ambulant patients[17]. However, as the disease progresses, the outcome measures change making it difficult to use a single outcome measure to analyse the patient. Studies are being carried out to create a uniform measure for the muscular dystrophies.

(see Outcome Measures Database)

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Sadly, there is no cure for Duchenne’s, but there are ways to help improve the individual’s quality of life and provide help for the stage they are in.

Mobility aids will be given to help the child be as independent as possible. This can include a walker in the beginning phases and can progress to a motorized wheelchair. In-home hoists are useful for the carers when they need help to transfer the child. Standing frames also become useful when the child can no longer stand on their own. This helps the child gain the benefits of standing, such as increased bone density, and stretching the muscles even if the child cannot stand on their own[18]. Knee-ankle-foot orthosis may be used as well. They have been found to prolong the child’s independent mobility[19]. These should be used alongside mobility aids, such as a zimmer frame [20]. Staying as active as possible is recommended. Bedrest can make the muscle-weakening worse[21].

Steroids are commonly prescribed for children with DMD, and are the only palliative treatment[22]. Steroids have been shown to increase the child’s muscle strength and functional ability[23]. Steroids may help delay the child becoming wheelchair dependent, however, there may be side effects[23]. Another group of medications that have been shown to be helpful are Beta-Blockers[24]. Heart and respiratory function slowly decline in these children and these drugs are used to help manage both these problems[25].

Some families may consider surgery for their child. Common surgeries for Duchenne’s boys include foot surgery, insertion of a feeding tube and spinal surgeries to correct scoliosis, which may occur from being wheelchair dependent[26]. There are many facts to consider before surgery, such as the effect general anaesthesia has on the cardiac and respiratory systems, which are already compromised in children with DMD[27]. Families need to weigh the advantages of the surgery with the risk before making a decision. For example, evidence has been found that surgery to correct scoliosis has improved respiratory function[28], and it also improves the cosmetic appearance and comfort of the child [29], however depending on the child’s cardiac and respiratory function there may be concerns about how anaesthesia will affect them.

There is no cure for DMD at present. The proactive symptom-based multidisciplinary team (MDT) management and access to non-invasive ventilation have enabled improved survival into adulthood[30]. Males with DMD, with intervention, can now be expected to live until their 30's and 40's[31]

For optimal management, a multidisciplinary care team who may be involved in the care include Neurologist, Cardiologist, Orthopedist, Pulmonologist, Medical Geneticist, Physical therapist and Occupational therapist.[32][33][34]

Preschool Age[edit | edit source]

Usually, at this stage, the child will be well and not need much treatment. What you will usually be offered is:

- Provide information about DMD and patient support groups.

- Referral to a specialist team (for example, a paediatrician or neurologist, physiotherapist and a specialist nurse) to monitor child health.

- Advice about the right level of exercise.

- Genetic advice for the family.

Age 5-8 Years[edit | edit source]

Between the ages of 6-11, there is a steady decline in muscle strength and by the age of 12 most children are wheelchair bound[35]. There are further complications surrounding children being dependent on wheelchairs, such as scoliosis and respiratory problems[36]. Some support may be needed for the legs and ankles. For example, using night-time ankle splints, or with a knee-ankle-foot orthosis. There is no evidence of significant benefit from any intervention for increasing ankle range of motion[37].

Treatment with corticosteroids can help to maintain the child's muscle strength. This involves taking medication such as prednisolone or deflazacort as a long-term treatment, either continuously or in repeated courses.

8 Years-Late Teenage Years[edit | edit source]

At some time after the age of 8 years, the child's leg muscles become significantly weaker. Walking gradually gets more difficult, and a wheelchair is needed. The age at which this happens varies from person to person. Often it is around age 9-11 years, although with corticosteroid treatment, some boys can walk for longer.

After the child starts needing a wheelchair, this is also the time that complications tend to begin, so it is important to monitor the boy's health and to treat any complications early.

Practical support and equipment will be needed at this stage, for example, wheelchairs and adaptations to the child's home and school.

Counselling and emotional support for the child and family may be helpful.

Late Teenage Years-Twenties[edit | edit source]

At this stage, muscle weakness becomes more problematic. Increasing help and adaptations are needed. Complications such as chest infections are likely to increase, so more medical monitoring and treatment are required.

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy is essential to the management of Duchenne’s. It is important to monitor the physical symptoms of the condition and physiotherapy can help keep the child active for as long as possible. Physiotherapists will work with the parents and carers and provide them with information and manual skills that will be helpful for the child.

Contractures are one of the major side effects that a physiotherapist will address. They will do these through a stretching routine, which can also be taught to the parents[38].

Physiotherapists will also be responsible for advising the parents on any orthoses, such as AFOs, and referring them with a paediatric orthotist[39]. They will also help families choose what mobility aids and equipment the child might need.

In the early stages of the condition, the physiotherapist will be involved in helping keep the child active. During later stages of the condition, the physiotherapist will help more with respiratory issues as well[39].

Physiotherapists will monitor the child’s posture in sitting, lying and standing[40]. They can inform the parents of ways to help the child sit, stand and lie in optimal positions using pillows or splints. A sleep system and night splints may be recommended for nighttime to help maintain the child’s posture over a long period of time[39].

Many physiotherapists use the NorthStar Ambulatory Assessment in order to objectively monitor the child’s progression. Initiated in 2003, it is a tool designed specifically for children with DMD and has the child perform up to 17 activities, including standing, head-raising, hopping and running[41]. This assessment is used only for children who are still able to walk. It is standardized with each child given the same instructions and their ability given a score of 0-2[42]. It is easy to administer and can be completed in approximately 10 minutes[41]. These are useful when consulting with other medical practitioners and letting them know where the child is physical condition.

Due to the wasting of the muscle caused by the lack of dystrophin, DMD patients will struggle with many everyday activities. Physiotherapists can help with the management of presenting neuromusculoskeletal problems. They can help slow the regression of range of motion, muscle strength, daily function, work to improve gait pattern and posture/alignment [31]. Physiotherapy can also address the pain that the patient may be experiencing. As the patient's walking and standing abilities decline the physiotherapist may choose to implement a standing program [43].

Pharmacology[edit | edit source]

In the ambulant stage, chronic cortical steroid treatment is an accepted practice. Glucocorticoid, a type of corticosteroid, is a standard of care among DMD patients. The use of steroids has been shown to help improve muscle strength and function, delay the loss of ambulation, and help maintain cardiac and respiratory function. Due to the fact that it helps with muscle strength, cortical steroids also reduce the risk of scoliosis.[44]

Treatment plans may vary, with some patients taking steroids every day or every second day. Different dosages may also be taken.

As with all medications, there are side effects which should be taken under consideration when treating the patient. Examples of know side effects are:

- Cushingoid features

- Weight gain and growth inhibition

- Impaired fat and glucose metabolism

- Fluid retention and hypertension

- Osteoporosis with increased risk of vertebral fractures

- Cataracts[44].

Respiratory Care[edit | edit source]

Respiratory function should be routinely checked in DMD patients. This allows physicians to monitor who may need help with assisted coughing and ventilation in the future. Examples of what evaluation of respiratory function should include are:

- Spirometric measurements of FVC, FEV, and maximal mid-expiratory flow rate

- Maximum inspiratory and expiratory pressure

- Peak cough flow.

Carbon dioxide levels should also be monitored[45].

Airway clearance is of importance to prevent atelectasis and pneumonia. A variety of manual techniques can be used in clinical practice to help clear the patient's airways. Manually assisted coughing techniques are useful in patients who have a low cough peak flow rate (below 160 L/min) because self-clearance of their airways are not adequate. Expiratory force can also be increased by applying pressure to the patient's upper abdomen during their natural cough. Other manual techniques include air stacking, glossopharyngeal breathing, and positive pressure application [45].

Along with manual techniques, mechanical techniques and mucus mobilization devices may also prove useful[45].

Complications[edit | edit source]

Anaesthetics[edit | edit source]

People with DMD need extra care if they have a general anaesthetic. Certain anaesthetic medicines can cause a harmful reaction for people who have DMD. Also, extra care for the chest and breathing is needed. It is important to have a pre-operative assessment and a senior anaesthetist providing anaesthetic care.

Osteoporosis[edit | edit source]

People with DMD may develop osteoporosis. This is due to lack of mobility and also to steroid treatment. It is important to prevent osteoporosis as far as possible. A good intake of vitamin D and calcium can help. Sometimes a blood test to check vitamin D levels is advised, and vitamin D supplements may be offered.

Joint and Spinal Complications[edit | edit source]

Muscle weakness can result in joint contractures. In DMD, it is often the ankle joint and Achilles' tendon which become tight. This can be treated either using orthotic devices or by surgical release of the tendon.

Scoliosis can occur due to muscle weakness. Usually, this happens at the beginning of the second decade of life, after the patient has lost ambulation[45]. Scoliosis can cause discomfort and is not helpful for posture and breathing. Treatments which can help are a spinal brace or surgery to the spine. Surgery has been shown to improve function and quality of life[46]. Surgery should be done while the patient still has sufficient lung function and before cardiomyopathy becomes a major risk factor when putting the patient under anaesthesia[45].

Nutrition and Digestion[edit | edit source]

Some children with DMD are prone to being overweight, especially if taking steroid treatment. Teenagers and adults with DMD may be underweight, due to loss of muscle bulk. Dietary advice can be helpful in these situations.

Constipation can be a symptom for anyone who is not mobile. This can be treated with laxatives and a high fibre diet.

In the later stages of DMD (as a young adult and older), people with DMD may have difficulty with chewing and swallowing food. They may need careful assessment and nutritional advice or supplements. If the problem is severe, then a gastrostomy may be needed.

Chest and Breathing Complications[edit | edit source]

During the teenage years, the breathing muscles weaken, causing shallow breathing and a less effective cough mechanism which can lead to chest infections. All individuals with DMD will present with restrictive lung disease[1]. Clearance techniques and non-invasive ventilation may help.

As the breathing muscles get weaker, oxygen levels in the blood may be reduced, more so while sleeping. Because this develops gradually, the symptoms may not be obvious. Possible symptoms are tiredness, irritability, morning headaches, night time waking and vivid dreams.

Vital capacity will increase as in a normal individual until the age of ten. After the age of ten, an individual's vital capacity will decrease by approximately 8-12% each year[1].

It is helpful if breathing problems are detected and treated early; so patients with DMD will usually be offered regular lung function tests once they start to have significant muscle weakness.

Cardiac (Heart) Complications[edit | edit source]

Teenagers and adults with DMD may develop cardiomyopathy. Cardiomyopathy generally develops around the age of 10 and by the age of 18 all individuals with DMD will present with cardiomyopathy [1]. In dilated cardiomyopathy, it becomes difficult for the heart to pump blood to the body because the chambers have become enlarged and the heart wall has thinned [1].

With DMD, the cardiomyopathy does not usually cause much in the way of symptoms. Possible symptoms are tiredness, leg swelling, shortness of breath or an irregular heartbeat. Cardiomyopathy can be helped by medication which seems to work best if started at an early stage before symptoms are noticed. So people with DMD are usually offered regular heart check-ups, starting from early childhood. The check-ups usually involve an ECG.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Other types of muscular dystrophy - particularly Becker's Muscular dystrophy, which is similar but progresses more slowly. The age of onset is usually later and clinical involvement milder. Muscle biopsy can be used as a standard for differentiating Becker's and Duchene's dystrophy.

Other myopathies- Creatinine Kinase levels are usually lower than those in DMD. Identification of deletion or mutation of relevant genes with DNA analysis confirms the diagnosis.

Polymyositis- Diagnosis is established by characteristic muscle biopsy findings of inflammation, including mononuclear invasion of non-necrotic muscle, CD8+ cytotoxic/suppressor T cells, macrophages, and absence of perifascicular atrophy of dermatomyositis. Usually, affects proximal and limb-girdle muscles.

Neurological causes of muscle weakness - eg, spinal cord lesions, spinal muscular atrophies, motor neurone disease, multiple sclerosis. These conditions are likely to have additional features, such as sensory loss, upper motor neuron lesion signs or muscle fasciculation.

Increased transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, which are produced by muscle as well as liver cells). The diagnosis of DMD should thus be considered before liver biopsy in any male child with increased transaminases[47].

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management

- Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary care

- Case Study

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Yiu E, Kornberg A. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Neurology India 2008;56(3):236-247.

- ↑ Muscular Dystrophy UK. Muscular Dystrophy UK Fighting Muscle-wasting Conditions. http://www.musculardystrophyuk.org/about-muscle-wasting-conditions/?gclid=CjwKEAjwpYeqBRDOwq2DrLCB-UcSJAASIYLjj2w3LQ3hI43XFhdWOw7wXT-6OFurebTSskU9ckZCdhoCZwfw_wcB (Accessed 28 April 2009)

- ↑ TECKLIN, J.S., 2006. Pediatric physical therapy / [editied by] Jan S. Tecklin. Philadelphia : Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2008; 4th ed.

- ↑ CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION., 2014. Facts About Muscular Dystrophy [online]. [viewed 2 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/musculardystrophy/facts.html

- ↑ ORPHANET., 2007. Duchenne and Becker Muscular Dystrophy [online]. [viewed 6 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Lng=EN&Expert=262

- ↑ FSH SOCIETY: FACIOSCAPULOJUMERAL MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY., 2010. About FSHD [online]. [viewed 5 October 2014]. Available from: https://www.fshsociety.org

- ↑ NHS., 2013. Muscular Dystrophy – Types [online]. [viewed 3 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Muscular-dystrophy/Pages/Symptoms.aspx

- ↑ SUOMINEN, T., BACHINSKI, L., AUVINEN, S., HACKMAN, P., BAGGERLY, K., ANGELINI, C., PELTONEN, L., KRAHE, R. and UDD, B., July 2011. Population frquency of myotonic dystrophy: higher than expected frequency of myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2) mutation in Finland.vol. 19, no. 7 pp. 776-82 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21364698

- ↑ Rae MG, O'Malley D. Cognitive dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a possible role for neuromodulatory immune molecules. J Neurophysiol. September 1 2016; 116(3):1304-15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5023417/.

- ↑ ALLEN, K. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. HealthandFitnessTalk.com. July 10, 2013, Available from: http://www.healthandfitnesstalk.com/tag/duchenne-muscular-distrophy/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 MEDLINEPLUS., 2014. Contracture deformity [online]. [viewed 2 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003185.htm

- ↑ HYDE, S.A., FLØYTRUP, I., GLENT, S., KROKSMARK, A., SALLING, B., STEFFENSEN, B.F., WERLAUFF, U. and ERLANDSEN, M., 2000. A randomized comparative study of two methods for controlling Tendo Achilles contracture in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscular Disorders. , vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 257-263.

- ↑ Armando Hasudungan. Muscular Dystrophy - Duchenne, Becker and Mytonic. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1uhhpjmzkw[last accessed 31/01/21]

- ↑ Lucas Ramirez. duchenne muscular dystrophy.wmv. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_aIAErxBskc [last accessed 31/01/21]

- ↑ ilm kidunya. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy by Dr Khalid Jamil Akhtar. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vbz6UG4iHhs [last accessed 25/05/13]

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 WALLACE, G.B. and NEWTON, R.W., 1989. Gowers' sign revisited. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Sep, vol. 64, no. 9, pp. 1317-1319.

- ↑ Outcome measures in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: sensitivity to change, clinical meaningfulness, and implications for clinical trials Joana Domingos Francesco Muntoni https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13634

- ↑ PT PRODUCTS., 2006. Continuing to Stand Tall [online]. [viewed 8 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.ptproductsonline.com/2006/10/continuing-to-stand-tall/

- ↑ GARRALDA, M.E., MUNTONI, F., CUNNIFF, A. and CANEJA, A.D., 2006. Knee–ankle–foot orthosis in children with duchenne muscular dystrophy: User views and adjustment. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. , vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 186-191.

- ↑ STEVENS, P.M. Lower Limb Orthotic Management of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Literature Review. American Academy of Orthotists & Prothetists2006, vol. 18, no. 4 pp. 111-119 Available from: http://www.oandp.org/jpo/library/2006_04_111.asp

- ↑ MEDLINEPLUS., 2014. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy [online]. [viewed 3 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000705.htm

- ↑ MUNTONI, F., FISHER, I., MORGAN, J.E. and ABRAHAM, D., 2002. Steroids in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from clinical trials to genomic research. Neuromuscular Disorders. , vol. 12, pp. S162-S165.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 ANGELINI, C. and PETERLE, E., 2012. Old and new therapeutic developments in steroid treatment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Myologica : Myopathies and Cardiomyopathies : Official Journal of the Mediterranean Society of Myology / Edited by the Gaetano Conte Academy for the Study of Striated Muscle Diseases. May, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 9-15.

- ↑ OGATA, H., ISHIKAWA, Y., ISHIKAWA, Y. and MINAMI, R., 2009. Beneficial effects of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of Cardiology. , vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 72-78.

- ↑ MATSUMURA, T., 2014. Beta-blockers in Children with Duchenne Cardiomyopathy. Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials. , vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 76-81.

- ↑ GREAT ORMOND STREET HOSPITAL CHILDREN’S CHARITY., 2012. Duchenne muscular dystrophy and surgery [online]. [viewed October 7 2014]. Available from: http://www.gosh.nhs.uk/medical-information/procedures-and-treatments/duchenne-muscular-dystrophy-and-surgery/

- ↑ SETHNA, N.F., ROCKOFF, M.A., WORTHEN, H.M. and ROSNOW, J.M., 1988. Anesthesia-related complications in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Anesthesiology. , vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 462-464.

- ↑ GALASKO, C.S., 1993. Medical management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). Mar 27, vol. 306, no. 6881, pp. 859.

- ↑ KAROL, L.A., 2007. Scoliosis in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. , vol. 89, no. suppl_1, pp. 155-162

- ↑ Manzur AY, Muntoni F; Diagnosis and new treatments in muscular dystrophies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009 Jul;80(7):706-14.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Tay S, Lin J. Current strategies in management of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Allowing patients to live with hope. Annals of the Academy of Medicine 2012;41(2):44-6.

- ↑ Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, Apkon SD, Blackwell A et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management [published correction appears in Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr 4]. Lancet Neurol. 2018; 17(3):251-267. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29395989.

- ↑ Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, Alman BA, Apkon SD, et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management.. Lancet Neurol. 2018; 17(4):347-361. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29395990.

- ↑ Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, Apkon SD, Blackwell A et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018; 17(5):445-455. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29398641.

- ↑ PROSENSA., 2014. DMD - Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy [online]. [viewed 3 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.prosensa.eu/hc-professionals/duchenne-muscular-dystrophy

- ↑ LORD, J., BEHRMAN, B., VARZOS, N., COOPER, D., LIEBERMAN, J.S. and FOWLER, W.M., 1990. Scoliosis associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Jan, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 13-17.

- ↑ Rose KJ, Burns J, Wheeler DM, North KN. Interventions for increasing ankle range of motion in patients with neuromuscular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Feb 17;2:CD006973.fckLR.

- ↑ BUSHBY, K., FINKEL, R., BIRNKRANT, D.J., CASE, L.E., CLEMENS, P.R., CRIPE, L., KAUL, A., KINNETT, K., MCDONALD, C. and PANDYA, S., 2010. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary care. The Lancet Neurology. , vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 177-189.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 DI MARCO, M., YIRRELL, J., TEWNION, J., KEDDIE, A., MELVILLE, P. and HARRISON, L. DMD Scottish Physiotherapy Managment Profile. Available from: http://www.smn.scot.nhs.uk/DMD%20management%20profile%20-%20version%2020b).pdf

- ↑ MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY CAMPAIGN., 2009. A Home Exercise Book: Physiotherapy management for Duchenne muscular dystrophy [online]. [viewed 7 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.muscular-dystrophy.org/assets/0001/1477/Physio_booklet_web.pdf

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 MAZZONE, E., MESSINA, S., VASCO, G., MAIN, M., EAGLE, M., D’AMICO, A., DOGLIO, L., POLITANO, L., CAVALLARO, F. and FROSINI, S., 2009. Reliability of the North Star Ambulatory Assessment in a multicentric setting. Neuromuscular Disorders. , vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 458-461.

- ↑ MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY CAMPAIGN. North Star Ambulatory Assessment [online]. [viewed 8 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.muscular-dystrophy.org/assets/0000/6388/NorthStar.pdf

- ↑ Bushby K et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary care. The Lancet Neurology 2010;9(2):177.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Goemans N, Buyse G. Current treatment and management of dystrophinopathies. Neuromuscular Disorders 2014;16(5):1-13

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 Finder JD et al. Respiratory care of the patient with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: ATS consensus statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170(4):456-65.

- ↑ Takaso M, Nakazawa T, Imura T, Okada T, Fukushima K, Ueno M, Takahira N, Takahashi K, Yamazaki M, Ohtori S, Okamoto H, Okutomi T, Okamoto M, Masaki T, Uchinuma E, Sakagami H.fckLRSurgical management of severe scoliosis with high risk pulmonary dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: patient function, quality of life and satisfaction. Int Orthop. 2010 Feb 16. [Epub ahead of print]

- ↑ Oxford Med Online Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (4 ed.) Alan E. H. Emery, Francesco Muntoni, and Rosaline C. M. Quinlivan 0.1093/med/9780199681488.003.0005