Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Purpose[edit | edit source]

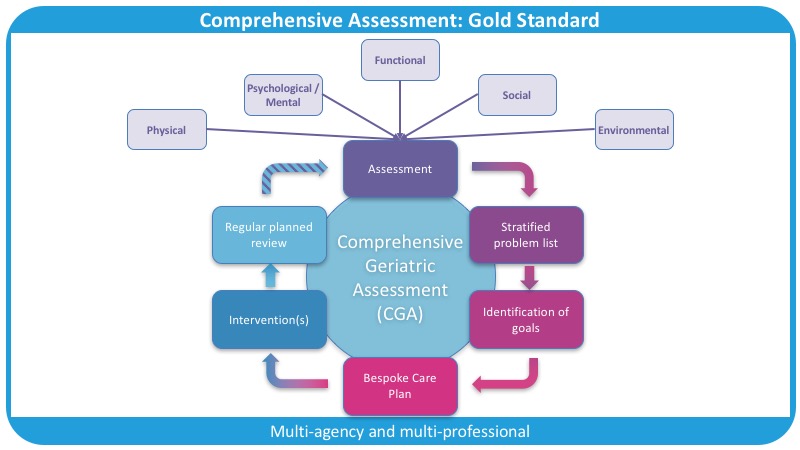

"Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is a multidimensional interdisciplinary assessment for evaluating the medical, psychological, physical functions and socioeconomic problems to detect unidentified and potentially reversible problems and develop a coordinated and integrated management plan for treatment and long-term care plan."[1]

It is an iterative, collaborative and multidimensional framework and process of assessment used to assess people living with frailty.[2] [3] The goal of a CGA is to identify an older person's needs and problems.[4] The CGA is considered the gold standard for managing frailty.[5]

- Older persons often have complex, multiple and interdependent problems (multimorbidity), which make their care more challenging than the care of younger people or those with just one medical problem.[6]

- The CGA is considered the best way to evaluate the health status and care needs of older adults.[7]

- The strength of the CGA lies in the fact it is a multidimensional holistic assessment of an older person that takes into consideration health and well-being.

The CGA allows healthcare practitioners to:

- create a problem list and a plan to address these issues

- this plan focuses on improving quality of life and an individual's ability to cope - particular importance is placed on what matters most to the patient[8]

The hallmarks of the CGA are that it:

- emphasises quality of life, functional status, prognosis, and outcome

- has greater depth and breadth than a standard evaluation

- involves many members of the interdisciplinary team and the use of any number of standardised instruments to evaluate aspects of patient functioning, impairments, and social supports[9][10]

- these features help differentiate the CGA from standard models of care

The Domains of the CGA[edit | edit source]

There are five domains at the centre of the CGA, and these form the framework for the assessment:

- Physical health and nutritional status (e.g. COPD, osteoarthritis, urinary incontinence, hearing or visual impairments)[11]

- Mental and emotional health (e.g. depression, cognition, vascular dementia)

- Functional issues (e.g. unable to shower or do the cleaning on their own)

- Social issues (e.g. lives alone, family far away)

- Environmental issues (e.g. stairs to the bedroom [fall risk], poor lighting)

By ensuring each domain is considered during every assessment, we are able to consider the whole person and their specific needs. The benefits gained by performing the CGA are only realised when all of the domains are covered.[8]

From the assessment and by using validated and reliable outcome measures, we can formulate and record a list of problems. By drawing on the expertise of the multidisciplinary (MDT) or interdisciplinary (IDT) team, the issues that are identified can then be addressed.

Each member of the team assesses domains relevant to their practice:

- the physician (usually a geriatrician or GP) assesses physical and mental health

- the pharmacist may undertake a medication review

- the nurse assesses various aspects of personal care (e.g. hygiene and continence)

- the physiotherapist may assess balance and mobility

- the occupational therapist may assess activities of daily living

- the social worker assesses social issues

- other members of the team may also be included if specific needs are identified (e.g. speech therapist, dietician)[6]

It is important to note that a team member might be involved in assessing more areas than those identified above. However, the key to teamwork in the CGA is to consider who is best placed to help the patient achieve the best outcomes at that time.[8]

Frailty[edit | edit source]

Frailty is a clinical state that is associated with an increased risk of falls, harm events, institutionalisation, care needs and disability/death.[12] It is the lack of inbuilt reserve.[8] An accumulation of deficits causes an individual to be unable to deal with new insults or changes in long-term conditions. The CGA allows these individuals to be assessed holistically, considering the biopsychosocial. It aims to identify strategies to help an individual cope with identified problems.[8]

More information on frailty and Rockwood's Accumulation of Deficits Model is available here.

The Physiotherapist's Role in the CGA[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists may be involved in the CGA in many different ways, depending on their speciality, their work setting, and the reasons a patient has been referred for physiotherapy. If a problem has been identified and you, as a physiotherapist, are able to act on it, then you should. If you are unable to act, a referral or signposting to an appropriate clinician is recommended.[8]

Physiotherapists are often involved in assessing/managing the following areas:

- Functional status

- functional status refers to an individual's ability to perform activities necessary or desirable in daily life

- functional status is directly influenced by health conditions, particularly in the context of an older person's environment and social support network

- Activities of daily living, including

- basic activities of daily living (BADLs), such as bathing, dressing

- instrumental or intermediate activities of daily living (IADLs), such as shopping, using a phone, taking medicine

- advanced activities of daily living (AADLs), such as being able to participate in social activities

- Gait speed

- gait speed can predict functional decline and early mortality in older adults

- according to Fritz et al.,[13] the average walking speed for geriatric adults is 1-1.4 m/sec. The preferred average walking speed in healthy adults, aged up to 50 years, is 1.4 m/sec. So a gait velocity of less than 1-1.4 m/sec could be considered clinically relevant.[14]

- assessing gait speed in clinical practice may help to identify individuals who need further evaluation, including those at increased risk of falls

- Falls/balance

- approximately one-third of community-dwelling persons age aged over 65 years and one-half of those aged over 80 years fall each year[15]

- patients who have fallen or have a gait or balance problem are at higher risk of having a subsequent fall and losing independence

- an assessment of fall risk should be integrated into the history and physical examination of all older persons[16]

As the role and scope of physiotherapy practice expand, we might become more involved in the management of Frailty Syndrome on a number of levels. Physiotherapists could start or be part of the iterative process of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment.

"Remember, it's about that iterative process. It's about signposting, referring on to those clinicians who need to be involved in that patient's care. It's not you doing all of the assessments. [...] It's about involving other clinicians in that time to do what they need to do." -- Scott Buxton[8]

Figure 1 illustrates the multi-agency and multi-professional approach that is key to a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment.[8]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Examples of outcome measures that could be employed include:

- Patient-Specific Functional Scale

- Barthel Index

- Katz ADL

- Functional Independence Measure (FIM)

- Elderly Mobility Scale

- The Balance Outcome Measure for Elder Rehabilitation (BOOMER)

- Romberg Test

- Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)

- Functional Reach

- 10 Metre Walk Test

Evidence[edit | edit source]

- "The evidence base for performing a CGA for inpatient patients with frailty is considered conclusive."[8] Compared to usual or standard models of care, which focus on single conditions by a single clinician without the CGA's iterative reviewing approach, the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment shows significant benefits in terms of increased independence and reduction of mortality.[8]

- A 2017 Cochrane review[17] found that older people are more likely to be alive and in their own homes at follow-up if they receive a CGA on admission to hospital.

- In 2017, Åhlund et al.[18] compared the physical fitness of older persons with frailty who were admitted to a CGA unit and those who received standard care. They found that "acute care of frail elderly patients at a CGA unit is superior to conventional care in terms of preserving physical fitness at 3 months follow-up."[18] And that CGA management may have a positive impact on outcomes like mobility, strength, and endurance.[18]

- The Number Needed to Treat of the CGA to avoid one unnecessary death or deterioration compared to general medical care is 13.[8] In comparison, the Number Needed to Treat for a statin is 60 for a heart attack and 268 for stroke. Statins are one of the most commonly prescribed and one of the most effective drugs at reducing death because of heart attack or stroke.[8]

- The Number Needed to Treat is a statistical value used to assess the benefits and harmful effects of medical interventions.[19]

"A Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is way more effective at reducing death than even some of the most effective and commonly prescribed drugs in the world. If that isn't compelling enough to start adopting this framework for your patient admissions and assessments, I don't know what is."[8] -- Scott Buxton

However, the evidence for using the CGA on patients who have had a hip fracture is inconclusive.[8] But a 2018 review by Eamer et al.[20] showed it had the following benefits:

- reduces the risk of mortality

- reduces the required post-discharge level of care

- reduces the length of stay and overall cost of health needs

However, the same systematic review found that readmission and delirium rates were not reduced.[8]

Frailty Screening[edit | edit source]

Patient screening can help primary care services and other services plan their caseload and prioritise their resources. However, it is important to note that there is no evidence to suggest systematic screening for frailty leads to more cost-effective treatments or improves patient health.

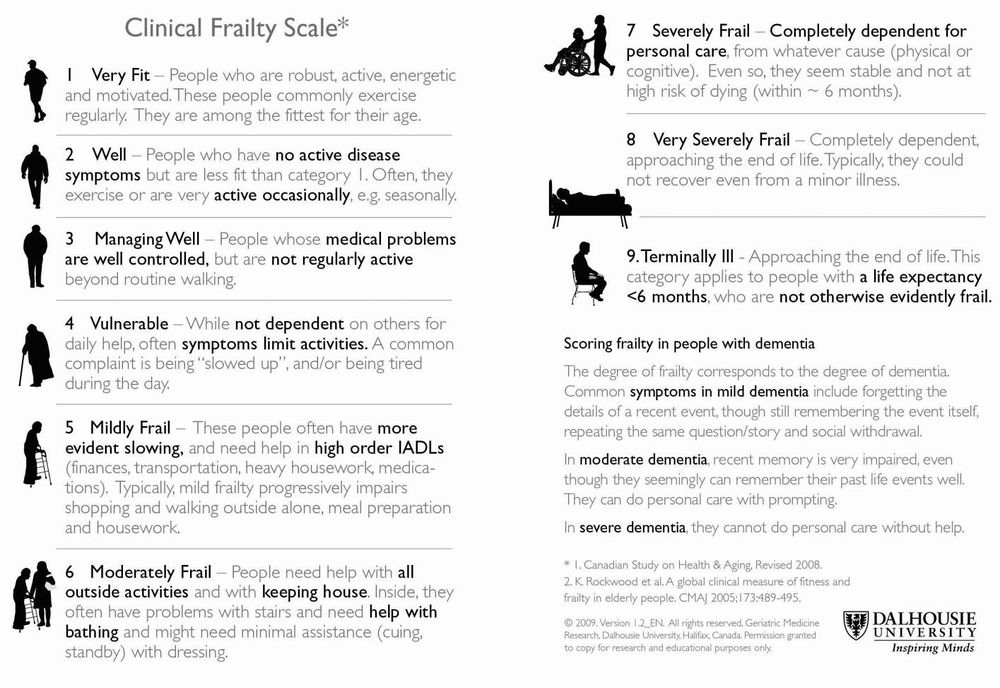

Scales that can be used to screen for frailty include:

- Fried's phenotype

- Clinical Frailty Scale (see Figure 2)

- The CGA should be performed when a person has a Clinical Frailty Scale score of 5 or more[8]

- Electronic Frailty Index

More information on these scales can be found here.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Choi J-Y, Rajaguru V, Shin J, Kim K, Comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary team interventions for hospitalized older adults: A scoping review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2023;104:104831.

- ↑ Garrard JW, Cox NJ, Dodds RM, Roberts HC, Sayer AA. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in primary care: a systematic review. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2020 Feb;32(2):197-205.

- ↑ Chen, Z., Ding, Z., Chen, C., Sun, Y., Jiang, Y., Liu, F. and Wang, S., 2021. Effectiveness of comprehensive geriatric assessment intervention on quality of life, caregiver burden and length of hospital stay: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC geriatrics, 21(1), pp.1-14.

- ↑ Stoop A, Lette M, van Gils PF, Nijpels G, Baan CA, De Bruin SR. Comprehensive geriatric assessments in integrated care programs for older people living at home: A scoping review. Health & social care in the community. 2019 Sep;27(5):e549-66.

- ↑ Nord M, Lyth J, Alwin J, Marcusson J. Costs and effects of comprehensive geriatric assessment in primary care for older adults with high risk for hospitalisation. BMC geriatrics. 2021 Dec;21(1):1-9.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wikipedia. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comprehensive_geriatric_assessment (last accessed 4.5.2019)

- ↑ Ouslander JG, Reyes B. Clinical problems associated with the aging process. In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 Buxton S. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and the Role of a Physiotherapist Course. Plus, 2020.

- ↑ CGA toolkit. Comprehensive geriatric assessment. Available from: https://www.cgakit.com/cga (last accessed 4.5.2019)

- ↑ thehealthline.ca Information Network. Introduction to the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Toolkit. AVailable from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ni2FaEboCZU&app=desktop (last accessed 4.5.2019)

- ↑ Lee H, Lee E, Jang IY. Frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessment. Journal of Korean medical science. 2019 Dec 20;35(3).

- ↑ Buxton S. An Introduction to Frailty course. Plus. 2020.

- ↑ Fritz S, Lusardi M. White paper:“walking speed: the sixth vital sign”. Journal of geriatric physical therapy. 2009 Jan 1;32(2):2-5.

- ↑ Howell D. Gait Deviation Associated with Pain Syndromes in the Pelvis and Knee Course. Plus, 2022.

- ↑ GOV.UK. Guidance, Falls: Applying all our health. Jan 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/falls-applying-all-our-health/falls-applying-all-our-health (last accessed:15/09/2020)

- ↑ Ward KT, Reuben DB. Comprehensive geriatric assessment. 2016 Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/comprehensive-geriatric-assessment (last accessed 15.09.2020)

- ↑ Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, Langhorne P, Burke O, Harwood RH, Conroy SP, Kircher T, Somme D, Saltvedt I, Wald H. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017(9). Available from: https://www.cochrane.org/CD006211/EPOC_comprehensive-geriatric-assessment-older-adults-admitted-hospital (last accessed 4.5.2019)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Åhlund K, Bäck M, Öberg B, Ekerstad N. Effects of comprehensive geriatric assessment on physical fitness in an acute medical setting for frail elderly patients. Clinical interventions in aging. 2017;12:1929. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5691905/ (last accessed 4.5.2019)

- ↑ Mendes D, Alves C, Batel-Marques F. Number needed to treat (NNT) in clinical literature: an appraisal. BMC medicine. 2017 Dec 1;15(1):112.

- ↑ Eamer G, Taheri A, Chen SS, Daviduck Q, Chambers T, Shi X, Khadaroo RG. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older people admitted to a surgical service. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018(1).