Physiology and Healing in Sport

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Stress is defined as any intrinsic or extrinsic stimulus that provokes a biological response. Stress response is the compensatory reaction to the stressor. Based on the severity, timing and type of evoked stimulus, stress can cause diverse actions on the body.[1] The severity of the physiological reaction to a stimulus is situationally dependent and highly individual.[2]

Physical Stress Theory[edit | edit source]

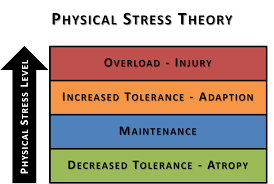

The physical stress theory suggests that tissues adapt to physical stresses by modifying their composition and structure to best meet the mechanical demands of routine loading. The direction, magnitude and time of the stressor establishes the overall level of exposure to physical stress. [3] Injury may occur due to a high-magnitude stress applied for a brief period, a moderate-magnitude stress applied to the tissue multiple times and/or a low-magnitude stress applied for a long duration.[3]

This theory proposes five qualitative responses to physical stress; atrophy, maintenance, hypertrophy, injury and death:[3][4]

- Atrophy: physical stress levels that are lower than maintenance range; subsequent stresses to tissues lead to decreased tolerance

- No apparent change: stressors that are in the maintenance range

- hypertrophy: stressors that exceed the maintenance range (overload); subsequent stress leads tissue to increased tolerance

- tissue injury: excessively high levels of physical stress

- tissue death: extreme deviations from the maintenance stress range that exceed the adaptive capacity of tissues[3]

Progressive overload refers to maintaining an adequate stimulus to match adaptive capacity.[5] However, suboptimal adaptations and negative effects on load tolerance can occur if the load is progressed too quickly. In this scenario, the risk of injury is increased.[6]

hat progressing load too quickly can have a negative effect on load tolerance as a result of suboptimal adaptations, thereby increasing the risk of nonfunctional overreaching or overtraining.5 These 2 conditions have been suggested as increasing the injury ris

Manipulation of load, frequency, rest and volume can maximise hypertrophic response.[7] To learn more about exercise priniciples, see Physiology In Sport.

Injured tissues become less tolerant to stress and present with inflammation immediately following injury. These tissues need to be protected from additional excessive stress until the acute inflammation abates.[3]To learn more read Inflammation and Soft Tissue Healing.

The optimal amount of stress should advance an athlete from homeostasis into over-reaching or acute fatigue. With adequate recovery time, adaptation and return to homeostasis occurs at a higher level of fitness. Conversely, inadequate recovery or too much stress will impede adaptation potentially facilitating injury. To maintain homeostasis in each athlete, monitoring individual stress response to training and competition is necessary.[8]

It has been proposed by Glasgow et al, (2015)[9] that rehabilitation optimal loading should integrate the entire neuromusculoskeletal system and should incorporate these 7 elements:

- target the appropriate tissues

- ensure loading through the functional ranges

- balance compressive, tensile, and shear loading

- vary the magnitude, direction, duration, and intensity

- incorporate neural overload; (6) adapt to individual characteristics

- be functional[9]

General Adaptation[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- General Principles of Exercise Rehabilitation

- Principles of Exercise Physiology and Adaptation

- Neuromuscular Adaptations to Exercise

- Bone Healing

- Soft Tissue Healing

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Yaribeygi H, Panahi Y, Sahraei H, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI journal. 2017;16:1057.

- ↑ Anderson GS, Di Nota PM, Metz GA, Andersen JP. The impact of acute stress physiology on skilled motor performance: Implications for policing. Frontiers in psychology. 2019 Nov 7;10:2501.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Mueller MJ, Maluf KS. Tissue adaptation to physical stress: a proposed “Physical Stress Theory” to guide physical therapist practice, education, and research. Physical therapy. 2002 Apr 1;82(4):383-403.

- ↑ Higgins JD, Wendland DM. The Use of the Physical Stress Theory to Guide the Rehabilitation of a Patient With Bilateral Suspected Deep Tissue Injuries and Hip Repair. Journal of Acute Care Physical Therapy. 2015 Dec 1;6(3):87-92.

- ↑ Plotkin D, Coleman M, Van Every D, Maldonado J, Oberlin D, Israetel M, Feather J, Alto A, Vigotsky AD, Schoenfeld BJ. Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations. PeerJ. 2022 Sep 30;10:e14142.

- ↑ Impellizzeri FM, Menaspà P, Coutts AJ, Kalkhoven J, Menaspà MJ. Training load and its role in injury prevention, part I: back to the future. Journal of athletic training. 2020 Sep;55(9):885-92.

- ↑ Scarpelli MC, Nóbrega SR, Santanielo N, Alvarez IF, Otoboni GB, Ugrinowitsch C, Libardi CA. Muscle hypertrophy response is affected by previous resistance training volume in trained individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2022 Apr 8;36(4):1153-7.

- ↑ Hamlin MJ, Wilkes D, Elliot CA, Lizamore CA, Kathiravel Y. Monitoring training loads and perceived stress in young elite university athletes. Frontiers in physiology. 2019 Jan 29;10:34.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Glasgow P, Phillips N, Bleakley C. Optimal loading: key variables and mechanisms. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015 Mar 1;49(5):278-9.