Parkinson's Pharmacotherapy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(Updated references) |

||

| (39 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:User Name|Andrew Bennett Lee Price]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | |||

== Introduction == | |||

[[File:Parkinson disease representation.jpeg|thumb|Parkinson's Disease]] | |||

[[Parkinson's|Parkinson’s]] disease (PD) is a gradually progressive [[Neurodegenerative Disease|neurodegenerative condition]]. The etiology and pathogenesis remain incompletely understood. There are currently no disease-modifying treatments for PD, with no neuroprotective agents currently available, treatment should only be initiated when quality of life is affected, and the potential benefits and side effects of these drug classes should be discussed with the patient<ref>Pharmaceutical Journal Parkinson’s disease: management and guidance Available: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/parkinsons-disease-management-and-guidance<nowiki/>(accessed 14.4.20220</ref>. | |||

The video below outlines briefly medication rational and major drug types{{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8VojsSvv4E|width}}<ref>PD care New York Taking Control: Medications for Parkinson's Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8VojsSvv4E (last accessed 8.11.2019)</ref> | |||

PD is caused by decreased [[dopamine]] production. Dopaminergic drugs are designed to replace the action of dopamine and form the mainstay of PD treatment at present. This may be achieved through drugs that are metabolised to dopamine, that activate the dopamine receptor, or that prevent the breakdown of endogenous dopamine. | |||

[https://www.epda.eu.com/living-well/therapies/surgical-treatments/deep-brain-stimulation-dbs/ Deep brain stimulation, stem cell therapy and gene therapy] are alternative approaches that aim to lower the need to medications. | |||

Understanding the impact of medication on both the movement and thought quality of people with Parkinson’s will help set goals and plans for [[Parkinson's Drugs Physiotherapy Implications|physiotherapy intervention]]. | |||

== Main Medications == | |||

# Levodopa: The mainstay of current PD treatment are levodopa-based preparations, designed to replace the dopamine in the depleted striatum. See [[Levodopa - Parkinson's|Levodopa in the Treatment of Parkinson's]] | |||

# Dopamine agonists: Stimulate the activity of the dopamine system by binding to the dopaminergic receptors. Dopamine agonists are often prescribed as an initial therapy for PD, particularly in younger patients. This approach allows for a delay in the use of levodopa, which may reduce the impact of the problematic motor complications | |||

# Drugs that prevent the breakdown of endogenous dopamine work by inhibiting the [[enzymes]] involved in dopamine metabolism, which preserves the levels of endogenous dopamine eg Monoamine Oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors, Catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors. | |||

# Anticholinergics: reduce the activity of the [[Neurotransmitters|neurotransmitter]] acetylcholine, by acting as antagonists at cholinergic receptors. While their role is limited and they are now prescribed infrequently, they may offer some benefit in improving rigidity and tremor in PD | |||

The | == Levodopa == | ||

The mainstay of current PD treatment are [[Levodopa - Parkinson's|levodopa]]-based preparations, designed to replace the dopamine in the depleted striatum. Dopamine itself is unable to cross the [[Blood-Brain Barrier|blood brain barrier]] (BBB) and cannot be used to treat PD. In contrast, the dopamine precursor levodopa is able to cross the BBB and can be administered as a therapy. After absorption and transit across the BBB, it is converted into the neurotransmitter dopamine by DOPA decarboxylase | |||

== Prevention of the Breakdown of Endogenous Dopamine Medications == | |||

'''MAO-B Inhibitors''' work by inhibiting the [[enzymes]] involved in dopamine metabolism, which preserves the levels of endogenous dopamine. While they are sometimes sufficient for control of symptoms in early disease, most patients ultimately require levodopa-based treatment. MAO-B inhibitors may also be used in combination with levodopa-based preparations, to allow for a reduction in the levodopa dose. Commonly used MAO-B inhibitors include selegiline (Deprenyl, Eldepryl, Zelapar) and rasagiline (Azilect). More recently, the drug safinamide (Xadago) was also approved for use in PD, which appears to have multiple modes of action, one of which is thought to be inhibition of MAO-B <ref name=":0">Zahoor I, Shafi A, Haq E. Pharmacological treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Exon Publications. 2018 Dec 21:129-44. Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536726/<nowiki/>(accessed 14.4.2022)</ref><ref name=":3">Teo KC, Ho SL. [https://translationalneurodegeneration.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2047-9158-2-19 Monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitors: implications for disease-modification in Parkinson’s disease]. Translational neurodegeneration 2013 Dec;2(1):19.</ref>. MAO-B inhibitors are generally well tolerated, with gastrointestinal side effects being the most common problem. Other adverse effects include aching joints, [[depression]], fatigue, dry mouth, insomnia, dizziness, confusion, nightmares, hallucinations, flu-like symptoms, indigestion, and [[headache]].<ref name=":0" /> | |||

'''Catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors''': another enzyme that is involved in dopamine degradation is COMT. These drugs are predominantly used as adjunctive therapy to levodopa, prolonging its duration of action by increasing its half-life and its delivery to the brain. COMT inhibitors come in the form of tablets and are not generally prescribed as monotherapy, as on their own they offer only limited effect on PD symptoms. Examples of COMT inhibitors include entacapone (Comtan), tolcapone (Tasmar), and opicapone (Ongentys). <ref name=":0" /> | |||

== | == Dopamine Agonist Medications == | ||

Dopamine receptor agonists came into the market for the treatment of PD in 1978. Dopamine agonists work by actively influencing dopamine receptors in the brain to produce more in-vivo dopamine, thus making it the preferential treatment early on in the disease process. <ref name=":8">Katzenschlager R, Poewe W, Rascol O, Trenkwalder C, Deuschl G, Chaudhuri KR, Henriksen T, Van Laar T, Spivey K, Vel S, Staines H. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442218302394 Apomorphine subcutaneous infusion in patients with Parkinson's disease with persistent motor fluctuations (TOLEDO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial]. The Lancet Neurology. 2018 Sep 1;17(9):749-59.</ref> Dopamine agonists are often prescribed as an initial therapy for PD, particularly in younger patients. This approach allows for a delay in the use of levodopa, which may reduce the impact of the problematic motor complications<ref name=":0" />. In general, dopamine agonists are not as potent as carbidopa/levodopa and may be less likely to cause dyskinesias. | |||

* Examples include: Pramipexole (Mirapex®), Pramipexole Dihydrochloride Extended-Release (Mirapex ER®), Ropinirole (Requip®), Ropinirole Extended-Release Tablets (Requip® XL™). | |||

* The main adverse effects seen after the intake of this medication include somnolence, withdrawal, and psychiatric disorders, such as confusion and hallucinations<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9">Auffret M, Drapier S, Vérin M. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40261-018-0619-3 Pharmacological insights into the use of apomorphine in Parkinson’s disease: clinical relevance]. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2018 Apr;38:287-312.</ref>. It is vital that the physical therapist is aware of such side effects to dictate the treatment. | |||

== Anticholinergic Medications == | |||

The medications that have so far been discussed are all aim to increase dopaminergic activity in the striatum. These reduce the activity of the [[Neurotransmitters|neurotransmitter]] [[acetylcholine]], by acting as antagonists at cholinergic receptors. While their role is limited and they are now prescribed infrequently, they may offer some benefit in improving rigidity and tremor in PD. Loss of dopaminergic neurons results in disturbance of the normal balance between dopamine and acetylcholine in the brain, and anticholinergic drugs may lead to restoration and maintenance of the normal balance between these two neurotransmitters.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

The main role of these drugs is in young patients at early stages of the disease for the relief of mild movement symptoms, particularly tremors and muscle stiffness. They are generally avoided in elderly patients or those with cognitive problems, due to an increased risk of confusion with this class of drugs<ref name=":0" />. | |||

== | * Examples of anticholinergics include benztropine, orphenadrine, procyclidine, and trihexyphenidyl (Benzhexol). | ||

* Common adverse effects of anticholinergic drugs include memory problems, drowsiness, constipation, sedation, urinary retention, blurred vision, tachycardia, and delirium. Increased side effects are typically seen in the elderly, when compared with younger adults<ref>Brocks DR. [https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=0277b08c308424821218ac2f0aa7092cb816f07c Anticholinergic drugs used in Parkinson's disease: An overlooked class of drugs from a pharmacokinetic perspective]. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 1999 May 1;2(2):39-46.</ref>. | |||

== | == Amantadine == | ||

Amantadine was initially developed as an antiviral medication to treat influenza in the 1960s; later it was realized that it can be used as a treatment for PD, and this use was confirmed in clinical trials. It acts as a nicotinic antagonist, dopamine agonist, and noncompetitive NMDA antagonist. | |||

Immediate-release amantadine is a mild agent that is used in early and advanced PD to help tremor. In recent years, amantadine has also been found useful in reducing dyskinesia that occur with dopamine medication. In 2017, an extended-release form of amantadine (Gocovri) was the first drug approved by the FDA specifically to treat dyskinesia in Parkinson's.<ref>PD org Amantadine Available;https://www.parkinson.org/Understanding-Parkinsons/Treatment/Prescription-Medications/Amantadine-Symmetrel (accessed 15.4.2022)</ref> | |||

== [[ | == Physiotherapy Implications == | ||

See [[Parkinson's Drugs Physiotherapy Implications]] | |||

== | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Parkinson's]] | |||

[[Category:Parkinson's - Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Pharmacology for Older People]] | |||

[[Category:Pharmacology]] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:55, 27 January 2023

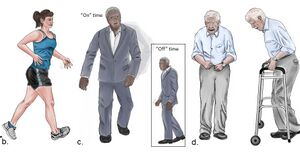

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a gradually progressive neurodegenerative condition. The etiology and pathogenesis remain incompletely understood. There are currently no disease-modifying treatments for PD, with no neuroprotective agents currently available, treatment should only be initiated when quality of life is affected, and the potential benefits and side effects of these drug classes should be discussed with the patient[1].

The video below outlines briefly medication rational and major drug types

PD is caused by decreased dopamine production. Dopaminergic drugs are designed to replace the action of dopamine and form the mainstay of PD treatment at present. This may be achieved through drugs that are metabolised to dopamine, that activate the dopamine receptor, or that prevent the breakdown of endogenous dopamine.

Deep brain stimulation, stem cell therapy and gene therapy are alternative approaches that aim to lower the need to medications.

Understanding the impact of medication on both the movement and thought quality of people with Parkinson’s will help set goals and plans for physiotherapy intervention.

Main Medications[edit | edit source]

- Levodopa: The mainstay of current PD treatment are levodopa-based preparations, designed to replace the dopamine in the depleted striatum. See Levodopa in the Treatment of Parkinson's

- Dopamine agonists: Stimulate the activity of the dopamine system by binding to the dopaminergic receptors. Dopamine agonists are often prescribed as an initial therapy for PD, particularly in younger patients. This approach allows for a delay in the use of levodopa, which may reduce the impact of the problematic motor complications

- Drugs that prevent the breakdown of endogenous dopamine work by inhibiting the enzymes involved in dopamine metabolism, which preserves the levels of endogenous dopamine eg Monoamine Oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors, Catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors.

- Anticholinergics: reduce the activity of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, by acting as antagonists at cholinergic receptors. While their role is limited and they are now prescribed infrequently, they may offer some benefit in improving rigidity and tremor in PD

Levodopa[edit | edit source]

The mainstay of current PD treatment are levodopa-based preparations, designed to replace the dopamine in the depleted striatum. Dopamine itself is unable to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and cannot be used to treat PD. In contrast, the dopamine precursor levodopa is able to cross the BBB and can be administered as a therapy. After absorption and transit across the BBB, it is converted into the neurotransmitter dopamine by DOPA decarboxylase

Prevention of the Breakdown of Endogenous Dopamine Medications[edit | edit source]

MAO-B Inhibitors work by inhibiting the enzymes involved in dopamine metabolism, which preserves the levels of endogenous dopamine. While they are sometimes sufficient for control of symptoms in early disease, most patients ultimately require levodopa-based treatment. MAO-B inhibitors may also be used in combination with levodopa-based preparations, to allow for a reduction in the levodopa dose. Commonly used MAO-B inhibitors include selegiline (Deprenyl, Eldepryl, Zelapar) and rasagiline (Azilect). More recently, the drug safinamide (Xadago) was also approved for use in PD, which appears to have multiple modes of action, one of which is thought to be inhibition of MAO-B [3][4]. MAO-B inhibitors are generally well tolerated, with gastrointestinal side effects being the most common problem. Other adverse effects include aching joints, depression, fatigue, dry mouth, insomnia, dizziness, confusion, nightmares, hallucinations, flu-like symptoms, indigestion, and headache.[3]

Catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors: another enzyme that is involved in dopamine degradation is COMT. These drugs are predominantly used as adjunctive therapy to levodopa, prolonging its duration of action by increasing its half-life and its delivery to the brain. COMT inhibitors come in the form of tablets and are not generally prescribed as monotherapy, as on their own they offer only limited effect on PD symptoms. Examples of COMT inhibitors include entacapone (Comtan), tolcapone (Tasmar), and opicapone (Ongentys). [3]

Dopamine Agonist Medications[edit | edit source]

Dopamine receptor agonists came into the market for the treatment of PD in 1978. Dopamine agonists work by actively influencing dopamine receptors in the brain to produce more in-vivo dopamine, thus making it the preferential treatment early on in the disease process. [5] Dopamine agonists are often prescribed as an initial therapy for PD, particularly in younger patients. This approach allows for a delay in the use of levodopa, which may reduce the impact of the problematic motor complications[3]. In general, dopamine agonists are not as potent as carbidopa/levodopa and may be less likely to cause dyskinesias.

- Examples include: Pramipexole (Mirapex®), Pramipexole Dihydrochloride Extended-Release (Mirapex ER®), Ropinirole (Requip®), Ropinirole Extended-Release Tablets (Requip® XL™).

- The main adverse effects seen after the intake of this medication include somnolence, withdrawal, and psychiatric disorders, such as confusion and hallucinations[5][6]. It is vital that the physical therapist is aware of such side effects to dictate the treatment.

Anticholinergic Medications[edit | edit source]

The medications that have so far been discussed are all aim to increase dopaminergic activity in the striatum. These reduce the activity of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, by acting as antagonists at cholinergic receptors. While their role is limited and they are now prescribed infrequently, they may offer some benefit in improving rigidity and tremor in PD. Loss of dopaminergic neurons results in disturbance of the normal balance between dopamine and acetylcholine in the brain, and anticholinergic drugs may lead to restoration and maintenance of the normal balance between these two neurotransmitters.[3]

The main role of these drugs is in young patients at early stages of the disease for the relief of mild movement symptoms, particularly tremors and muscle stiffness. They are generally avoided in elderly patients or those with cognitive problems, due to an increased risk of confusion with this class of drugs[3].

- Examples of anticholinergics include benztropine, orphenadrine, procyclidine, and trihexyphenidyl (Benzhexol).

- Common adverse effects of anticholinergic drugs include memory problems, drowsiness, constipation, sedation, urinary retention, blurred vision, tachycardia, and delirium. Increased side effects are typically seen in the elderly, when compared with younger adults[7].

Amantadine[edit | edit source]

Amantadine was initially developed as an antiviral medication to treat influenza in the 1960s; later it was realized that it can be used as a treatment for PD, and this use was confirmed in clinical trials. It acts as a nicotinic antagonist, dopamine agonist, and noncompetitive NMDA antagonist.

Immediate-release amantadine is a mild agent that is used in early and advanced PD to help tremor. In recent years, amantadine has also been found useful in reducing dyskinesia that occur with dopamine medication. In 2017, an extended-release form of amantadine (Gocovri) was the first drug approved by the FDA specifically to treat dyskinesia in Parkinson's.[8]

Physiotherapy Implications[edit | edit source]

See Parkinson's Drugs Physiotherapy Implications

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Pharmaceutical Journal Parkinson’s disease: management and guidance Available: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/parkinsons-disease-management-and-guidance(accessed 14.4.20220

- ↑ PD care New York Taking Control: Medications for Parkinson's Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8VojsSvv4E (last accessed 8.11.2019)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Zahoor I, Shafi A, Haq E. Pharmacological treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Exon Publications. 2018 Dec 21:129-44. Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536726/(accessed 14.4.2022)

- ↑ Teo KC, Ho SL. Monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitors: implications for disease-modification in Parkinson’s disease. Translational neurodegeneration 2013 Dec;2(1):19.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Katzenschlager R, Poewe W, Rascol O, Trenkwalder C, Deuschl G, Chaudhuri KR, Henriksen T, Van Laar T, Spivey K, Vel S, Staines H. Apomorphine subcutaneous infusion in patients with Parkinson's disease with persistent motor fluctuations (TOLEDO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2018 Sep 1;17(9):749-59.

- ↑ Auffret M, Drapier S, Vérin M. Pharmacological insights into the use of apomorphine in Parkinson’s disease: clinical relevance. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2018 Apr;38:287-312.

- ↑ Brocks DR. Anticholinergic drugs used in Parkinson's disease: An overlooked class of drugs from a pharmacokinetic perspective. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 1999 May 1;2(2):39-46.

- ↑ PD org Amantadine Available;https://www.parkinson.org/Understanding-Parkinsons/Treatment/Prescription-Medications/Amantadine-Symmetrel (accessed 15.4.2022)