Emphysema

Original Editors - Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.

Top Contributors - Valentina Mazzoni, Lucinda hampton, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Kim Jackson, Admin, WikiSysop, Mohit Chand, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Michelle Lee and Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

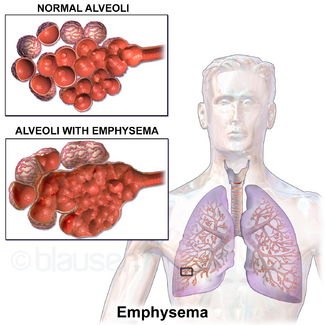

Pulmonary emphysema, a progressive lung disease, is a form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Emphysema is primarily a pathological diagnosis that affects the air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole. It is characterized by abnormal permanent enlargement of lung air spaces with the destruction of their walls (septa of alveoli) without any fibrosis and destruction of lung parenchyma with loss of elasticity.[1]

There are three types of emphysema:

- Centriacinar emphysema affects the alveoli and airways in the central acinus, destroying the alveoli in the walls of the respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts [2]

- Panacinar emphysema affects the whole acinus [2]

- Paraseptal emphysema is believed to be the basic lesion of pulmonary bullous disease [2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Emphysema, as a part of COPD, is an illness that affects a large number of people worldwide. In 2016, the Global Burden of Disease Study reported a prevalence of 251 million cases of COPD globally. Around 90% of COPD deaths occur in low and middle-income countries.

The prevalence of emphysema:

In United States is approximately 14 million, which includes 14% white male smokers and 3% white male nonsmokers.

It is slowly increasing in incidence primarily due to the increase in cigarette smoking and environmental pollution. Another contributing factor is decreasing mortality from other causes such as cardiovascular and infectious diseases. Genetic factors also play a significant role in determining the possibility of airflow limitation in patients.

Emphysema severity is significantly higher in the coal worker pneumoconiosis, and this is independent of smoking status.[1]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

The exact cause of Emphysema is still yet to be distinguished; however, research is suggesting the prevalence is strongly related to smoking, air pollutions and in some cases, occupation [3]. Another common association is the deficiency of the enzyme alpha₁-antitrypsin, which is the protein protecting the alveoli [4].

The prevalence of Emphysema within the smoking population is believed to increase as smoking is a major risk factor associated. It is thought to have a higher incidence in those with a lower socioeconomic background, therefore affecting lifestyle and environment, resulting in the likelihood of respiratory infection [5].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The alveoli and the small distal airways are primarily affected by the disease, followed by effects in the larger airways [4]. Elastic recoil is usually responsible for splinting the bronchioles open. However, with emphysema, the bronchioles lose their stabilizing function and therefore causing a collapse in the airways resulting in gas to be trapped distally[4].

There is an erosion in the alveolar septa causing there to be an enlargement of the available air space in the alveoli [4]. There is sometimes a formation of bullae with their thin walls of diminished lung tissue.

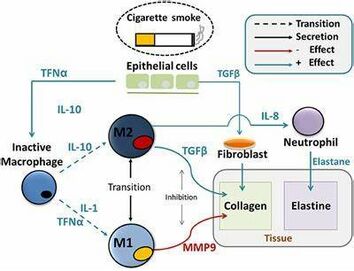

Smoking contributes to the development of the condition initially by activating the inflammatory process [3]. The inhaled irritants cause inflammatory cells to be released from polymorphonuclear leukocytes and alveolar macrophages to move into the lungs [3]. Inflammatory cells are known as proteolytic enzymes, which the lungs are usually protected against due to the action of antiproteases such as the alpha1-antitrypsin [3]. However, the irritants from smoking will have an effect on the alpha1-antitrypsin, reducing its activity. Therefore, emphysema develops in this situation when the production and activity of antiprotease are not sufficient to counter the harmful effects of excess protease production [3]. A result of this is the destruction of the alveolar walls and the breakdown of elastic tissue and collagen. The loss of alveolar tissue leads to a reduction in the surface area for gas exchange, which increases the rate of blood flow through the pulmonary capillary system [3].

Investigations[edit | edit source]

CT scan is a common method used to diagnosis emphysema. The observations mainly seen to identify emphysema are a decrease in lung attenuation and a decrease in the number and diameter of pulmonary vessels in the affected area [6].

Clinical Manifestations[edit | edit source]

Patients diagnosed with emphysema may complain of difficult/laboured breathing and reduced exercise capacity as their predominating symptoms [7]. The loss of the elastic recoil in the lungs leads to irreversible bronchial obstruction and lung hyperinflation, which increases the volume over normal tidal breathing and functional residual capacity [7].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The main aims of treating patients with Emphysema are to relieve symptoms and to improve quality of life [8][9]. To measure patients’ quality of life, the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and the Guyatt’s Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ) are often completed in order to measure the effectiveness of a treatment intervention [8].

Other outcome measures relevant include:

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Generally, the diagnosis for Emphysema can be based on clinical, functional and radiographic findings [10]. However, it is thought that mild Emphysema is not well detected on conventional chest radiography, therefore the use of pulmonary function tests (PFT) are often used to try and diagnose the condition [11].

In order to accurately diagnose Emphysema, the history of the patient’s condition needs to be fully understood [12]. The use of high-resolution CT scans is part of the standard procedure when trying to detect this condition as it is non-invasive and is found to be sensitive in detecting pathological changes related to Emphysema [12].

Physiotherapy and Other Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy management for Emphysema is commonly associated with similar management of COPD. The use of a pulmonary rehabilitation programme consisting of exercise and education can be designed by the physiotherapist along with other members of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) in order to maximise the patients, exercise capacity, mobility and also self-confidence [4]. The other MDT members can consist of a respiratory nurse and dietitians, as well as the physiotherapist in the hope to treat each patient like an individual and meet their specific needs by tailoring a programme to suit them [4].

Pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with severe symptoms and multiple exacerbations reduces dyspnea and hospitalizations. [1]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

As COPD is the umbrella term used for diseases like Emphysema, the prevention strategies are very similar. The most common suggestion for preventing emphysema, and such, is to stop smoking, and to avoid breathing in any harmful pollutants [13].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Pahal P, Avula A, Sharma S. Emphysema. [Updated 2021 Feb 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482217/#!po=74.0000(accessed 24.5.2021p

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Hochhegger B, Dixon S, Screaton N, Cardinal V, Marchiori S, Binukrishnan S, Holemans J, Gosney J, McCann C, Emphysema and smoking related lung diseases. The British Institute of Radiology 2014; 20 (4).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Mattison S, Christensen M. The pathophysiology of emphysema: Considerations for critical care nursing practice. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 2006; 22: 329-337.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Hough A. Physiotherapy in respiratory and cardiac care. Hampshire: Cengage Learning EMEA, 2014

- ↑ Haas F, Haas SS. The Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema Handbook. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2000.

- ↑ Newell, J. CT of Emphysema. Radiologic Clinics of North America 2002; 40 (1): 31-42.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Visca D, Aiello M, Chetta A. Cardiovascular function in pulmonary emphysema. BioMed Research International 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Harper R, Brazierm JE, Waterhouse JC, Walters SJ, Jones NMB, Howard P.Comparison of outcome measures for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in an outpatient setting. Thorax 1997; 52: 879-887.

- ↑ Naunheim KS, Wood DE, Mohsenifar Z, Sternberg AL, Criner GJ, DeCamp MM, Deschamps CC, Martinez FJ, Sciurba FC, Tonascia J, Fishman AP. Long-term follow-up of patients receiving lung-volume-reduction surgery versus medical therapy for severe emphysema by the national emphysema treatment trial research group. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2006; 82 (2): 421-443.

- ↑ Klein JS, Gamsu G, Webb WR, Golden JA, Muller NL. High-resolution CT diagnosis of emphysema in symptomatic patients with normal chest radiographs and isolated low diffusing capacity. Radiology 1992; 182: 817-821.

- ↑ Sanders C, Nath PH, Bailey WC. Detection of Emphysema with computed tomography correlation with pulmonary function tests and chest radiography. Investigative Radiology 1988; 23: 262-266.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Zaporozhan J, Ley S, Eberhardt R, Weinheimer O, Svitlana I, Herth F, Kauczor H-U. Paired inspiratory/expiratory volumetric thin-slice CT scan for emphysema analysis: comparison of different quantitative evaluations and pulmonary function test. American College of Chest Physicians 2005; 128 (5): 3212-3220.

- ↑ National Health Service. NHS Choices. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease/Pages/Introduction.aspx (accessed 02 June 2015)