Bronchiectasis

Introduction[edit | edit source]

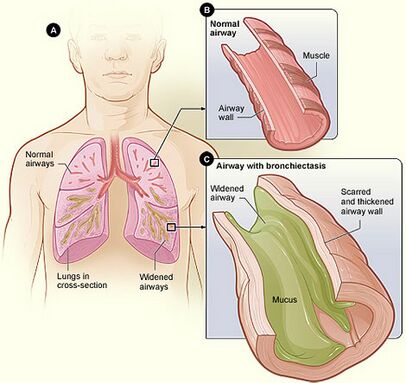

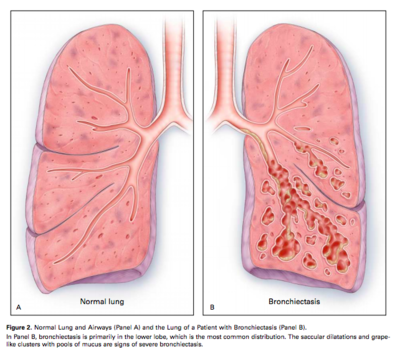

Bronchiectasis is a chronic lung disease identified by persistent and lifelong widening of the bronchial airways and weakening of the function mucociliary transport mechanism due to repeated infection. These airway changes allow for easier bacterial invasion and extra mucus pooling in the widened airways, making them prone to infection[1].

The condition is characterised by a persistent cough with excess amounts of mucus and, frequently, airflow obstruction together with episodes of worsening symptoms.[2]

Watch this informative 2 minute video on Bronchiectasis.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The cause of bronchiectasis is not always known. Some conditions known to cause bronchiectasis that affect or damage airways are:

- Conditions that damage the airways, raising the risk of lung infections. For example: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; pneumonia; measles; inherited disorders eg Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia, Cystic Fibrosis

- Immunodeficiency: predisposes the person to lung infections.

- Pulmonary Diseases eg asthma, COPD

- Lung infections: may cause damage to the walls of the airways, for example tuberculosis (TB), whooping cough, measles, pneumonia, or fungal infections, particularly in childhood.

- Conditions that cause an airway blockage, such as a growth or a noncancerous tumour, regurgitated stomach acid, or inhaled objects that become stuck and block an airway.[1][2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Bronchiectasis predominance is not clearly understood. The incidence of bronchiectasis has risen over the past few years. It can exist in any age group, but it generally occurred in childhood during the pre-antibiotic period. New evidence shows that bronchiectasis disproportionately affects women and older individuals.[1]

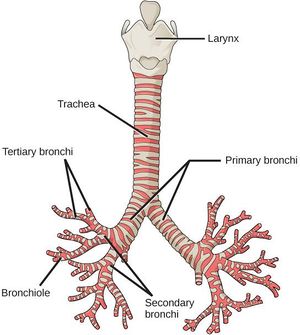

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Bronchiectasis involves inflammation of the airway walls, specifically the bronchial walls [4]. The main area that is affected in bronchiectasis is the bronchi [4]. For more detailed anatomy see Lung Anatomy

The cilia are also damaged in bronchiectasis and the mucociliary clearance of mucus is adversely affected. NB. Cilia line the airway and are attached to the epithelium. They are hair-like with tiny hooks on the tip to grab the mucous and help move the mucus up to the throat [4].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The three most significant mechanisms that contribute to the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis are recurrent infections, airway obstruction, and peribronchial fibrosis.[1]

- The process begins with inflammatory damage to the bronchial walls, which then stimulates the formation of excess thick mucus [4].

- The warm and moist environment of the lungs combines with the mucus to cause further inflammation and obstruction, creating an excellent environment for infection [4].

- The thick mucus crushes the cilia and causes further damage. The immune response releases toxic inflammatory chemicals (i.e. neutrophils), as well as leads to fibrosis and bronchospasm if persistent[4].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Bronchiectasis relies on both a clinical and radiological diagnosis.

Currently, a high-resolution CT scan is the gold standard for diagnosing bronchiectasis [4]. Findings are: bronchial wall dilation; failure of the bronchi to taper; visualisation of bronchi in the outer 1-2cm of the lung fields.[5]

Microbiology can also be used to identify the bacteria present during an exacerbation [4]. A sputum sample is sent off and the results are returned with the incidence of bacterial colonization measured [4].

Medical History[edit | edit source]

- History of childhood infection or childhood respiratory symptoms

- Family history of bronchiectasis, especially cystic fibrosis

- Smoking history

- Presence of symptoms to suggest a systemic inflammatory disorder (joint problems, skin rash, muscle pain)

- Duration and severity of symptoms

- Frequency of infective exacerbations

Objective Examination[edit | edit source]

- Peripheral examination for signs of chronic lung disease e.g nail changes (clubbing) occur in some forms of bronchiectasis

- Cough quality, strength and sputum production

- Auscultation: Bronchiectasis is characterised by focal or generalised noises (crepitations, crackles, wheeze,) heard with the stethoscope.[5]

- Dyspnoea on exertion seems to be a major clinical manifestation as it is experienced by three out of four patients.

- Stress incontinence can also be a result of excess coughing. [4].

- Exacerbations can occur several times a year and are identified by four or more of the following signs and/or symptoms: change in sputum, increased dyspnoea, increased cough, fever of greater than 38°, increased wheeze, decreased exercise tolerance, fatigue, lethargy, and radiographic signs of a new infection[4].

Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment of bronchiectasis involves promoting sputum clearance, using positional physiotherapy, and early and aggressive treatment of pulmonary infections. Some clients require chronic prophylactic administration of antibiotics.

In cases where bronchiectasis is severe and causes significant morbidity, surgical resection of the affected lobe may be of the benefit provided sufficient respiratory reserve exists.

When both lungs are extensively involved (e.g. cystic fibrosis) lung transplantation can be considered.[6]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy has a very valuable role in aiding with symptoms of bronchiectasis. Since mucociliary clearance is reduced to about 15% of normal, patients tend to cough more[4]. Physiotherapy treatments are aimed at aiding secretion clearance, managing fatigue induced by the effort of ineffective clearance and increased coughing.

See Chest Physiotherapy for a comprehensive look at the most effective techniques.

The most common treatments are:

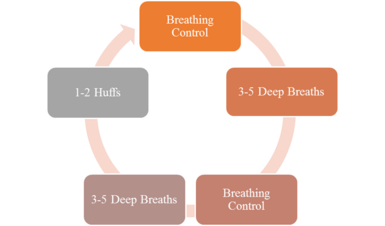

- Active Cycle of Breathing Technique see link

- Forced expiration technique, sometimes referred to as a huff. It is part of the ACBT but can be used alone. A huff is very effective at clearing secretions especially when combined with other airway clearance techniques.[7]

- Manual Therapy is a popular treatment technique and is often used when the patient is fatigue or experiencing an exacerbation of symptoms. It describes techniques that involve external forces to the chest wall to loosen mucus and includes any combination of percussion, shaking, rib springing, vibrations and over pressure[8]. Because of the nature of the technique, it is contraindicated in patients that are taking anticoagulants or that have osteoporosis[9].

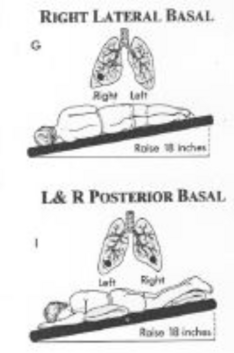

- Postural Drainage is an effective treatment that incorporates gravity-assisted techniques to help clear secretions from specific segments of the lungs, and often requires tilting the head down to clear secretions from the middle and lower lobes. See link

- Autogenic Drainage is a technique that utilises breathing control to clear secretions from the airways. The aim is to vary the depth, rate and location of lung volumes during respiration to move secretions from the smaller airways to the larger airways for easier expectoration.

- Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) is a technique that describes breathing against resistance and can be performed either through a device or against pursed lips.

- High-Frequency Chest Wall Oscillation is achieved by wearing a vest that emulates chest physiotherapy. The vest applies positive pressure air pulses to the chest which causes vibrations that loosen and thin mucus, This along with an intermittent cough or huff assists with the clearance of secretions. Allows people to perform therapy in their own time.

- Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation. Intrapulmonary percussive ventilator (IPV) is a machine that delivers short bursts of air through a mouthpiece that vibrates the airway walls[10]. It is indicated for short-term use when other techniques are contraindicated or have proved ineffective.

- Intermittent Positive Pressure Breathing (IPPB). A technique used to provide short term or intermittent mechanical ventilation via mouthpiece or mask for the purpose of augmenting lung expansion and delivering aerosol medication. IPPB may be applied to intubated as well as nonintubated patients

- Physical Exercise is recommended for respiratory conditions, including bronchiectasis with the aim of improving aerobic capacity and, fitness and endurance. A study by Lee et al concluded that exercise resulted in short term improvements and had an impact on dyspnoea and fatigue, and resulted in fewer exacerbations over a 12 month period[11].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The following could be used, many exist:

- Dyspnoea Management Questionnaire

- Incentive Spirometry

- Borg Rating Of Perceived Exertion

- Leicester Cough Questionnaire[12]

- 2 Minute Walk Test

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bird K, Memon J. Bronchiectasis.2017 Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430810/ (accessed 20.10.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 AIHW Bronchiectasis Available:https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/bronchiectasis/contents/bronchiectasis (accessed 20.10.2022)

- ↑ salamhossein. Bronchiectasis Animation - What is Bronchiectasis? Video.mp4. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uNeprw1rsgE [last accessed 18/5/15]

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Hough A. Physiotherapy in Respiratory and Cardiac Care: an evidence-based approach. 4th ed. Hampshire: Cengage Learning EMEA, 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bronchiectasis.com Bronchiectasis Dx Available: https://bronchiectasis.com.au/bronchiectasis/diagnosis-2/how-is-it-diagnosed (accessed 20.10.2022)

- ↑ Radiopedia Brochiectasis Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/bronchiectasis (accessed 20.10.2022)

- ↑ Van der Schans CP. Forced expiratory manoeuvres to increase transport of bronchial mucus: a mechanistic approach. Monaldi archives for chest disease= Archivio Monaldi per le malattie del torace. 1997 Aug;52(4):367.

- ↑ Syed N, Maiya AG, Siva Kumar T. Active Cycles of Breathing Technique (ACBT) versus conventional chest physical therapy on airway clearance in bronchiectasis–a crossover trial. Advances in Physiotherapy. 2009 Jan 1;11(4):193-8.

- ↑ Diehl N, Johnson MM. Prevalence of Osteopenia and Osteoporosis in Patients with Noncystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis. South Med J. 2016;109(12):779-83

- ↑ Paneroni M, Clini E, Simonelli C, et al. Safety and efficacy of short-term intrapulmonary percussive ventilation in patients with bronchiectasis. Respir Care 2011;56:984–8.

- ↑ Lee AL, Hill CJ, Cecins N, et al. The short and long term effects of exercise training in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis--a randomised controlled trial. Respir Res 2014;15:44.

- ↑ Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, Singh SJ, Morgan MD, Pavord ID. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax. 2003 Apr 1;58(4):339-43.