Lumbar Assessment

Original Editors - Ben Vandoorne

Top Contributors - Admin, Rachael Lowe, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Jess Bell, Vandoorne Ben, Carin Hunter, Naomi O'Reilly, Kai A. Sigel, Lucinda hampton, Aminat Abolade, Evan Thomas, Simisola Ajeyalemi, 127.0.0.1, Rishika Babburu, WikiSysop and Wanda van Niekerk

Notes on Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment of the lumbar spine should allow clinical reasoning to include appropriate data collection tests from those listed below.

Examination procedures should be performed from standing-sitting-lying and pain provocation movements saved until last.

The subjective assessment (history taking) is by far the most important part of the assessment with the objective assessment (clinical testing) confirming or refuting hypothesis formed from the subjective.

Subjective

[edit | edit source]

The subjective examination is one of most powerful tools a clinician can utilize in the examination and treatment of patients with LBP. The questions utilized during this process can improve the clinician’s confidence in identification of sinister pathology warranting outside referral, screening for yellow flags which may interfere with PT interventions, and assist in matching PT interventions with a patient’s symptoms. History not only is the record of past and present suffering but also constitutes the basis of future treatment, prevention and prognosis.

Detailed page on subjective assessment of the lumbar spine

Patient Intake[edit | edit source]

- Self‐report (patient history, past medical history, drug history, social history)

- Performance‐based outcome measures

- Region‐specific questions

- What is the patient’s age?

- What is the patient’s occupation?

- What was the mechanism of injury?

- How long has the problem bothered the patient?

- Where are the sites and boundaries of pain?

- Is there any radiation of pain? Is the pain centralizing or peripheralizing

- Is the pain deep? Superficial? Shooting? Burning? Aching?

- Is the pain improving? Worsening? Staying the same?

- Is there any increase in pain with coughing? Sneezing? Deep breathing? Laughing?

- Are there any postures or actions that specifically increase or decrease the pain or cause difficulty?

- Is the pain worse in the morning or evening? Does the pain get better or worse as the day progresses? Does the pain wake you up at night?

- Which movements hurt? Which movements are stiff?

- Is paresthesia (a “pins and needles” feeling) or anesthesia present?

- Has the patient noticed any weakness or decrease in strength? Has the patient noticed that his/her legs have become weak while walking or climbing stairs?

- What is the patient’s usual activity or pastime? Before the injury, did the patient modify or perform any unusual repetitive or high-stress activity?

- Which activities aggravate the pain? Is there anything in the patient’s lifestyle that increases the pain?

- Which activities ease the pain?

- What is the patient’s sleeping position? Does the patient have any problems sleeping? What type of mattress does the patient use (hard, soft)?

- Does the patient have any difficulty with micturition?

- Are there any red flags that the examiner should be aware of, such as a history of cancer, sudden weight loss for no apparent reason, immunosuppressive disorder, infection, fever, or bilateral leg weakness?

- Is the patient receiving any medication?

- Is the patient able to cope during daily activities?

Special Questions

[edit | edit source]

Red Flags[edit | edit source]

Although uncommon, non musculoskeletal conditions (such as those listed below) may present as LBP in approximately 5% of patients presenting to primary care offices (see table)Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title.

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Cancer

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Lumbar stenosis

- Lumbar disc herniations

- Vertebral fracture

- Spinal infection

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

During the investigation you must pay attention to any ‘red flags’ that might be present indicating serious pathology. Koes et al (2006)[1] mentioned the following ‘red flags’:

- Onset age < 20 or > 55 years

- Non-mechanical pain (unrelated to time or activity)

- Thoracic pain

- Previous history of carcinoma, steroids, HIV

- Feeling unwell

- Weight loss

- Widespread neurological symptoms

- Structural spinal deformity

Read more about red flags in spinal conditions

Other Flags[edit | edit source]

It is also important to screen for other (yellow, orange, blue and black) flags.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Fear‐Avoidance Belief Questionnaire

Acute Low Back Pain Screening Questionnaire

The Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale

Hendler 10-Minute Screening Test for Chronic Back Pain Patients

The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire

Investigations

[edit | edit source]

Has the patient had any other investigations such as radiology (Xray, MRI, CT, ultrasound) or blood tests?

Objective[edit | edit source]

When assessing the lumbar spine, the examiner must remember that referral of symptoms or the presence of neurological symptoms often makes it necessary to “clear” or rule the lower limb pathology. Many of the symptoms that occur in the lower limb may originate in the lumbar spine. Unless there is a history of definitive trauma to a peripheral joint, a screening or scanning examination must accompany assessment of that joint to rule out problems within the lumbar spine referring symptoms to that joint.

Observation

[edit | edit source]

Movement Patterns[edit | edit source]

How does the patient enter the room?

A posture deformity in flexion or a deformity with a lateral pelvic tilt, possibly a slight limp, may be seen.

How does the patient sit down and how comfortably/ uncomfortably does he or she sit?

How does the patient get up from the chair? A patient with low back pain may splint the spine in order to avoid painful movements.

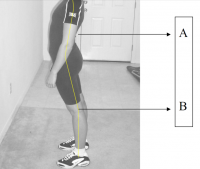

Posture[edit | edit source]

Other observations[edit | edit source]

- body type

- attitude

- facial expression

- skin

- hair

- leg length discrepancy (functional, structural)

Functional Tests

[edit | edit source]

Functional Demonstration of pain provoking movements

Squat test - to highlight lower limb pathologies. Not be done with patients suspected of having arthritis or pathology in the lower limb joints, pregnant patients, or older patients who exhibit weakness and hypomobility. If this test is negative, there is no need to test the peripheral joints (peripheral joint scan) with the patient in the lying position[2].

Movement Testing[edit | edit source]

- AROM (flexion 40-60, extension 20-35, side flexion 15-20 - looking for willingness to move, quality of movement, where movement occurs, range, pain, painful arc, deviation)

- Overpressure (at the end of all AROM if they are pain free, normal end feel should be tissue stretch)

- Sustained positions (if indicated in subjective)

- Combined movements (if indicated in subjective)

- Repeated movements (if indicated in subjective)

- Muscle Strength (resisted isometrics in flex, ext, side flex, rotation; core stabilty, functional strength tests)

Neurologic Assessment[edit | edit source]

| [3] |

- Myotomes -

- L2: Hip flexion

- L3: Knee extension

- L4: Ankle dorsiflexion

- L5: Great toe extension

- S1: Ankle plantar flexion, ankle eversion, hip extension

- S2: Knee flexion

- Dermatomes

- Reflexes

- Patellar (L3–L4)

- Medial hamstring (L5–S1)

- Lateral hamstring (S1–S2)

- Posterior tibial (L4–L5)

- Achilles (S1–S2)

- Neurodynamic testing - slump, SLR, PKB and modified versions where appropriate

Circulatory Assessment[edit | edit source]

If indicated it may be necessary to perform a haemodynamic assessment.

Palpation[edit | edit source]

| [4] |

It is crucial for a reliable diagnosis and intervention of treatment to adequately palpate the lumbar processi.

Within the scientific world there has been a debate about the palpation of the processi spinosi because scientists assumed that often different persons indicated the processi on a different place (Mckenzie et al)[5]. However, Snider et al (2011)[6] have shown that the indicated points of the different therapists lie that the distance between the indicated points of the different therapists is much smaller than it had always been claimed. Obviously there were differences because some therapists have more experience and others have more anatomical knowledge. Also the difference in personality between the therapists led to differences in locating the processi.

Furthermore, this investigation has proven that it is more useful to indicate different points instead of just 1 point. Also it has been proven that a manual examination to detect the lumbar segmental level is highly accurate when accompanied by a verbal subject response (Philips 1996).[7]

There are of course elements that hinder the palpation. For example, a BMI (body mass index) of 30kg/m2 considerably diminishes the accuracy (Ferre et al)[8]. Anatomical abnormalities might also cause problems. The abnormality of the 12th rib leads, for example, to a negative palpatory accuracy in the region L1-L4 for all therapists. [9]

- Passive Intervertebral Motion (PPIVMs, PAIVMs)

- Muscle Tone

Clear Adjacent Joints[edit | edit source]

| [10] |

- Thoracic spine - seated rotation with combined movements and overpressure

- Sacroiliac joints - various tests have been described to clear the SIJ such as Gillet test, sacral clearing test, cluster tests

- Hips - PROM with overpressure

- Knees and ankles - should also be cleared for restrictions that may affect movement patterns

Special Tests[edit | edit source]

For neurological dysfunction:

- Centralization/peripheralization

- Cross straight leg raise test

- Femoral nerve traction test

- Prone knee bending test or variant

- Slump test or variant

- Straight leg raise or variant

For lumbar instability:

| [11] |

- H and I test

- Passive lumbar extension test

- Prone segmental instability test

- Specific lumbar torsion test

- Test for anterior lumbar spine instability

- Test for posterior lumbar spine instability

For joint dysfunction:

- Bilateral straight leg raise test

- One-leg standing (stork standing) lumbar extension test

- Quadrant test

For muscle tightness:

- 90–90 straight leg raise test

- Ober test

- Rectus femoris test

- Thomas test

Other tests:

Order of Assessment[edit | edit source]

Standing

Sitting

Supine

Prone

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Koes B.W. van Tulder M. W., Thomas S.; diagnosis and treatment of low back pain; BMJ volume 332, 17 june 2006; 1430-1434

- ↑ Magee, D. Lumbar Spine. Chapter 9 In: Orthopedic Physical Assessment. Elsevier, 2014

- ↑ Scott Bainbridge. Lumbar Spine Examination. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IijlOJPHk1s[last accessed 19/08/15]

- ↑ tsudpt11's channel. Maitland Lumbar PAIVM (skeletal model). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t0OCzavA6SY[last accessed 19/08/15]

- ↑ McKenzie AM, Taylor NF. Can physiotherapists locate lumbar spinal levels by palpation? Physiotherapy 1997;83: 235-9.

- ↑ Karen T. Snider, Eric J. Snider, Brian F. Degenhardt, Jane C. Johnson and James W. Kribs; palpatory accuracy of lumbar spinous processes using multiple bony landmarks. ournal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; 2011

- ↑ Phillips D. R.; Twomey L. T.; A comparison of manual diagnosis with a diagnosis established by a uni-level lumbar spinal block procedure; manual therapy, march 1996, pages 82-87

- ↑ 3. Ferre RM, Sweeney TW. Emergency physicians can easily obtain ultrasound images of anatomical landmarks relevant to lumbar puncture. Am J Emerg Med 2007;25:291-6.

- ↑ Karen T. Snider, Eric J. Snider, Brian F. Degenhardt, Jane C. Johnson and James W. Kribs; palpatory accuracy of lumbar spinous processes using multiple bony landmarks. ournal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; 2011

- ↑ Physical Therapy Nation. Lumbar and SIJ Examination. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EL5tXj81Q8M[last accessed 19/08/15]

- ↑ Ed Schrank. Lumbar Stability Tests. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jDoZ4d09M9Q[last accessed 19/08/15]