Subcortical Vascular Dementia: Case Study

Top Contributors - Bomi Jang, Jonathan Tam, Kiley Praught, Emily Mulligan, Sofia Lamarche, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Lucinda hampton, Harrison Mah and Koon Kei Gary Lai

This fictional case study is produced by first-year physiotherapy students at Queens’ University for education purposes.

Abstract[edit | edit source]

The purpose of this case study page is to describe a fictional case of an older adult with a new diagnosis of subcortical vascular dementia with symptoms affecting her daily function and quality of life. The authors have described a possible presentation for this patient and subsequent treatment plan. Interventions suggested for this patient include progressive balance, functional, and gait training to work towards goals that the patient has identified. After progressing through the training program, the patient will be transitioned to community exercise and physical activity (such as tai chi) to maintain and mitigate the effects of the disease. Technology will also be used in her recovery in the form of serious games. Outcomes include patient reports as well as formal measurements such as MMTs, ROM, Berg Balance Scale, gait speed, MiniBESTest, TUG with and without dual task, ABC scale, MoCA, Mini-Cog, and Romberg (performed by PT and other HCPs). Outside of physiotherapy, referrals that would be beneficial were highlighted including to a neurologist, occupational therapist, speech-language pathologist, social worker/ therapist, as well as community care and the Alzheimer’s Society. Although this patient is experiencing a progressive disease, it is important to optimize her function to allow her to continue in activity and participation in her life, as outlined in this case.

List of Abbreviated Words[edit | edit source]

ABC Scale = Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale

ADL = activities of daily living

AROM = active range of motion

BADL = basic activities of daily living

BBS = Berg Balance Scale

BMI = body mass index

CBMS = Community Balance and Mobility Scale

C/S = cervical spine

FAB = Frontal Assessment Battery Test

GP = general practitioner

HCP = healthcare provider

HEP = home exercise program

HR = heart rate

IADL = instrumental activities of daily living

ICF = International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

L/E = lower extremity

LHIN = Local Health Integration Networks

MCID = minimal clinically important difference

MMT = manual muscle test

MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment

MVC = motor vehicle collision

OT = occupational therapist

PCP = Primary Care Practitioner

PPA = Primary Progressive Aphasia

PSW = personal support worker

PT = physiotherapist/physical therapy

ROM = range of motion

RR = respiratory rate

SLP = speech language pathologist

SLT = speech and language therapy

TIA = transient ischemic attack

TV = television

TUG = Timed Up and Go

U/E = upper extremity

WNL = within normal limits

y/o = years old

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Dementia is a broad term characterizing a spectrum of symptoms that impacts one’s brain function (Arvanitakis et. al, 2020). The condition presents through a progressive and incurable neurodegenerative disease that can impact an individual’s physical, mental, and emotional health (Arvanitakis et. al, 2020). Worldwide, an estimated 55 million people are living with dementia with this population more heavily favoring low and middle income countries (Arvanitakis et. al, 2020). The projected increase in this number demands acknowledgement and accessibility of treatment across interdisciplinary health care professions. A challenging aspect of health care intervention on dementia is the relative inability to reverse disease progression and restore normal function (Arvanitakis et. al, 2020). Due to this limitation, intervention should be focused on slowing progressive losses and optimizing function in each stage of the disease to maintain the best quality of life.

The role of physiotherapy related to dementia treatment can encompass several interventions targeting things such as; pain relief, physical deconditioning, and balance impairments (Hall et. al, 2016). Across current literature, it is suggested some of the most effective physiotherapy interventions for individuals in early stage dementia include exercises to maintain mobility, developing fall prevention programs, and learning adaptations to maximize independence of the patient in their daily activities (Hall et. al, 2016). Furthermore, related literature suggests that incorporating physical activity, of even mild to moderate intensity a few times a week, into treatment interventions can help combat Dementia’s cognitive deficits (Ning et. al 2020).

Vascular Dementia is a common type of dementia described by a blockage of blood supply to the brain resulting in the brain cells to be deprived of oxygen and nutrients, leading to death (Arvanitakis et. al, 2020). Vascular Dementia is further divided into two subtypes: subcortical dementia and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (Arvanitakis et. al, 2020). Subcortical Vascular Dementia (also known as Binswanger’s Disease), as seen in the following case study, is caused by a disease of the small vessels in the brain resulting in reduced blood flow (Arvanitakis et. al, 2020).

The current case study illustrates a patient recently diagnosed with stage 3 subcortical vascular dementia, who presents at an outpatient neurological rehabilitation centre following a fall. The patient suffers several cognitive deficits related to concentration, communication, and organization. The patient also demonstrates physical deficits manifested in psychomotor slowness, poor balance, weakness, and overall slow motor function, impacting their ability to complete daily activities. The purpose of the following case study serves as a documentation of the effects of neurological physical therapy treatment interventions during rehabilitation on the patient’s experience and outcomes and helps the learner walk through a possible case scenario of Subcortical Vascular Dementia.

Client Characteristic[edit | edit source]

Pseudonym: B.B.

Age: 60 y/o

Gender: Female

Ethnicity: Caucasian

Marital status: Married (husband)

Occupation: Retired secretary for the government

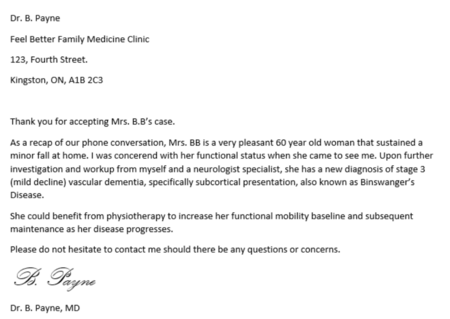

BB’s physician called to inquire if a physiotherapist at the outpatient neurological rehabilitation clinic could accept B.B.’s case. B.B. presented to her primary care practitioner (PCP) after a minor fall 2 weeks ago. After concerns noted from PCP, the PCP and neurologist have done a workup and have diagnosed the patient with stage 3 (mild decline) vascular dementia, specifically a subcortical presentation, also known as Binswanger’s Disease. Focus of physiotherapy will be to improve her baseline function as much as possible and then maintain function throughout the course of her progressive disease. (Roman et al., 2002)

PCP Referral letter:

PICTURE!!!

Primary condition: Vascular dementia subtype subcortical dementia, Stage 3 (mild decline)

Nature of the condition: Mild decline, Stage 3

- Physical manifestations including psychomotor slowness and weakness, as well as decreased balance, and coordination

- Cognitive manifestations: confusion, difficulty paying attention or concentrating, trouble organizing thoughts, trouble making plans and communicating them, slowed thinking, memory loss and speech difficulties

Primary reason the patient was referred: Recent diagnosis with vascular dementia and concerns with subsequent poor functional status from PCP and neurologist.

Patient herself has noticed having difficulty generating speech at times, finds it easier for herself to give simpler answer as it is less frustrating and effortful, patient herself has noticed progressive balance issues/feeling unsteady, reduced activity due to fear of falling, has noticed reduced ability to be independent in BADLs and IADLs, also concerns from husband. (Roman et al., 2002)

Relevant comorbidities: Hypertension (well-managed with medications by PCP) (Roman et al., 2002), high BMI (due to sedentary lifestyle), no previous major traumas/MVC/falls (minor fall 2 weeks ago; no major injuries as per PCP), past abdominal surgery (C-section) 35 years ago

Examination Finding[edit | edit source]

(Note: assessed over multiple sessions)

Subjective[edit | edit source]

History of Present Illness (Roman et al., 2002)

- Patient has had a recent new diagnosis with vascular dementia from her physician and neurologist specialist.

- The patient had a minor fall at home, which led to her going to the doctor’s office. Although the fall was minor, her physician then had some concerns over balance, gait, etc.

- The patient herself and her physician has noticed progressive balance issues/feeling unsteady, reduced activity due to fear of falling.

- Patient has noticed having difficulty generating speech at times, finds it easier for herself to give simpler answer as it is less frustrating and effortful

Diagnostic Tests

Results of tests from neurologist

- Neurologist performed the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) test to differentiate between Alzeihmer’s disease and Vascular dementia (Oguro et al., 2006)

- CT scan of the brain shows the brain lesions typical of the disease including widespread, microscopic areas of damage to the brain resulting from the thickening and narrowing (atherosclerosis) of arteries that supply blood to the subcortical areas of the brain. (Văcăraș et al., 2020)

- Past Medical History:

- Abdominal surgery (C-section) 35 years ago,

- No other major trauma, MVCs, falls, or surgeries

- Minor fall 2 weeks prior

- Controlled hypertension

- Medication

- Prinivil 10 mg once a day for high blood pressure ("Prinivil, Zestril (lisinopril) dosing", 2021)

- Daily women’s multivitamin (One a Day Women’s 50+)

- Health Habits

- Sedentary lifestyle, activity level has decreased over past 5 years

- Non-smoker, has never smoked in the past

- Occasionally consumes alcohol in social settings, thinks on average 2 drinks/ week

- No other substance use

- Social History

- Main support system is husband (65 y/o, in good health) (married for 40 years)

- Has some friends close by but when in need of support (more so emotional support)

- One adult son who lives two hours away

- Two young grandchildren (3 and 5 years old), enjoys spending time with them and babysitting, but has had decreased ability to do so recently

- Enjoys reading, knitting, and watching TV in her down time

- Current functional status (Roman et al., 2002)

- Independent in BADLs

- Currently experiencing difficulty with IADLs, notably including anything that requires more demands on coordination and balance (cooking, cleaning, etc), and anything in the community

- More comfortable ambulating around the house

- Finds community ambulation difficult (ex. grocery shopping, running errands, etc.) due to being unsteady

- Finds transfers in and out of her bed difficult because of soft mattress, relies on husband for assistance

- Transfers in and out of chairs inconsistent

- Experiences some shortness of breath and feels tired/ weak after 2 minutes of walking

- Patient has noticed having difficulty coming up with words at times, finds it easier for herself to give simpler answer as it is less frustrating and effortful

- Lives in Bungalow with husband, two stairs to get into the house with a side railing on both sides

- Functional history

- Previously independent in all BADLs and IADLs

- No difficulty to ambulate in community

- No use of gait aid

- An hour long walk every weekend with her husband

- Family history

- Father died of ischemic stroke at age of 70 (Roman et al., 2002)

- Mother died of natural causes at age of 90

- No siblings

- Precautions:

- Confusion at times

- Falls risk - guard closely

Objective[edit | edit source]

- Observation: (Roman et al., 2002)

- Forward head posture, postural increased kyphosis in thoracic spine

- Patient appears alert and oriented, occasional moments of confusion (husband compensating)

- Observed patient walking into the room on first visit, seemed to be a little unsteady, no use of gait aid

- Slow exaggerated movements when watching patient come into exam room

- Vital signs: BP: 115/80 mmHg (controlled with medication as per above), HR: 87 bpm, RR: 17 bpm

- Range of Motion (ROM)

- Impaired ROM

- slightly limited cervical extension ¾ ROM

- limited trunk extension ½ ROM

- All other ROM are within normal limits

- Impaired ROM

- Strength (MMT)

- Reduced strength bilaterally, notably in L/E

| Muscle Group | Right | Left |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder Flexion | 4- | 4- |

| Shoulder Extension | 4 | 4 |

| Elbow Flexion | 4- | 4 |

| Elbow Extension | 4 | 4+ |

| Hip Flexion | 3+ | 3+ |

| Hip Extension | 3+ | 3 |

| Knee Flexion | 3 | 3 |

| Knee Extension | 3+ | 3 |

| Ankle Dorsiflexion | 3 | 3 |

| Ankle Plantar Flexion | 3+ | 3+ |

- Reflexes:

- Hyperactive muscle stretch reflexes throughout

- Exaggerated deep tendon reflexes (clonus)

- Hoffman sign bilaterally

- Extensor plantar response on Babinski bilaterally

- Skin sensation: intact U/E and L/E sensation to light touch, pinprick, vibration, and temperature

- Myotomes/dermatomes: normal in U/E and L/E

- Romberg test:

- Eyes open: 23 seconds (able to stand feet together with significant sway)

- Eyes closed: 5 seconds (needed to took a step to recovery her balance) (Gras et al., 2015)

- Coordination

- Finger to nose test: mild dysmetria observed bilaterally, clumsy with few impaired pursuits, increased length of time taken to accomplish task, unable to perform with a moving target (Bergeron et al., 2016)

- Mild dysmetria observed when performing heel-to-shin test bilaterally

- Combined Cortical Sensations

- Stereognosis, barognosis, and graphesthesia were unremarkable.

- Double simultaneous stimulation: There was no extinction to double simultaneous stimulation.

- Kinesthesia/ proprioception

- Limb matching test: Mild loss of accuracy in L/E bilaterally

- 6 minutes walk test: 136 m

- 1st break for 56 seconds at 80m mark

- 2nd break for 123 seconds at 120m mark

- 10m walk test

- Gait speed over the test was measured to be 0.73m/s

- 3D motion analysis of gait showed: (Roman et al., 2002)(Beauchet et al., 2008)(Kyrdalen et al., 2019)(Kovacs et al., 2005)

- Gait was noticeably slow

- Wide base

- Reduced step length

- Normal arm swing

- Decrease in stride length

- Increase in support phase, reduced swing time

- An increase in stride-to-stride variability

- Inconsistency between sides

- Poor weight transfer

- Features over course of gait cycle

- Initial stance: Minor decrease in ankle dorsiflexion and knee flexion

- Mid-stance: Minor decrease in knee extension, hip extension, and ankle dorsiflexion

- Pre-swing: Minor decrease in knee flexion and ankle plantarflexion

- Early and mid-swing: minor decrease in knee flexion

- Late swing: minor decrease in knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion

- Findings are consistent with MMT of lower extremities

- Inability to perform tandem walk

- Berg balance Scale (BBS): 36/56

- MiniBESTest

- Timed Up and Go (TUG): 17.5 seconds

- Total score: 20/28 (Magnani et al., 2019).

- Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scales (ABC): 43%

- Cognitive Tests

- Timed Up and Go (TUG) Dual-Task testing:

- Cognitive challenge: counting backwards in sets of 7 from 100: 28.1 seconds (Cedervall et al., 2020).

- Physical challenge: carrying a cup with half full water: 32.5 seconds

- Mini-Cog Test (Short memory test with a simple clock drawing test): 1

- On-site occupational therapist performed a MoCA: 25/30 (rapid screening instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction) (Văcăraș et al., 2020).

- Timed Up and Go (TUG) Dual-Task testing:

Clinical Impression[edit | edit source]

B.B. is a previously independently functioning 60 year old female presenting to outpatient neurological rehabilitation following a minor fall 2 weeks prior. B.B. presents with several marked cognitive and physical impairments that hinder her usual activity level. At time of referral to outpatient rehabilitation, B.B. presents with various physical deficits such as diffuse bilateral lower extremity weakness, impaired coordination and imbalance. Noted cognitive deficits include; attention impairment, inability to maintain concentration and communication difficulties. However, psychomotor slowness appears to be the most pronounced impairment relating to both physical and cognitive functioning. The interaction of these deficits are reflected in B.B.’s slow and unsteady motor functions, and seemingly unorganized and limited communication abilities. Previous transient ischemic attack, subjective and objective assessment findings and hallmark characteristic of psychomotor slowness correlate with the diagnoses of stage three Vascular Dementia otherwise known as Binswanger Disease. The diagnosis of this condition has impacted B.B.’s independence. B.B. has difficulty completing her BADLs and IALDs due to imbalance and perceived fear of falling and is frustrated due to inability to easily organize and communicate thoughts. B.B. is hoping to gain strategies to combat these deficits in order to be able to feel comfortable babysitting her grandchildren again, as she has felt isolated from them in the process of her diagnosis. Previous independent function, limited medical history, age, available support from her husband and stage of diagnosis are factors indicating that B.B. is a suitable candidate for neurological rehabilitation in an outpatient setting. Interventions focused on improving balance, fall prevention, and strengthening could support achieving optimal function for the current stage of diagnosis of this progressive neurodegenerative disease.

Problem list:

- Progressive balance deficits causing increased falls risk reflected objectively through BERG Balance score of 36/56, and subjective reports of feeling unsteady.

- Right and left lower extremity weakness shown through decreased MMT scores.

- Marked slowness in motor function presented through TUG time of 17.5 seconds, 6 minute walk test distance of 136m with 2 breaks and observed slowness throughout gait parameters.

- At risk of developing further complications, accelerating progression, and intensifying disease impact through comorbidities and unfavourable lifestyle habits such as high BMI, hypertension, and sedentary lifestyle.

- Memory impairments reported through subjective history as forgetfulness and objective assessment as a positive result in a mini-cog test.

- Slow and uncoordinated movements reflected in observation of finger-to-nose test and inability to complete task under more complex conditions such as a moving target. Dysmetria noted in heel-knee-shin test bilaterally.

- Frustration related to impaired cognitive functioning causing difficulties related to thought organization, communication and concentration.

- Feelings of concern related to lack of independence in daily activities and being a burden due to reliance on social support system.

- lack of education on diagnosis and typical disease progression.

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Patient-centered treatment goals

These goals were developed in consultation with the circle of care, including the patient and caregiver as well as the ICF model.

Short Term

- Body structure and function: Increase LE strength, evidenced by MMTs to 4/5 bilaterally in 4 weeks by daily strengthening exercises (HEP).

- Body structure and function: Improve balance evidenced by a berg balance score to 50/56 in 4 weeks by taking part in a falls prevention/ balance program.

- Activity: To be able to ambulate in the community

Long Term Goals

- Body structure and function: Patient will maintain ROM within normal limits in 12 weeks

- Activity: Patient will be able to walk 400m (in a closed environment) without a gait aid within 6 minutes in 6 weeks

- Participation: Increase community participation by signing up for weekly tai chi class in 5 weeks.

- Participation: To be able to independently perform groceries shopping in 6 weeks

B.B's. treatment plan

Physical therapy (PT) is indicated in this case. PT has shown to improve or slow loss in mobility, strength, balance and endurance (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2007; Rolland, 2012; Forbes, et.al, 2014). These improvements correlated to improved functional independence in mobility and ADLs in individuals with dementia (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2007; Rolland, 2012; Forbes, et al., 2014). There are no guidelines to best practice and many studies do not state the therapeutic interventions used; therefore, this warrants the need for further research in this area and for this population. However, consistent with general best practice guidelines, we will focus on making therapy engaging, functional, and task-oriented.

Before starting therapy, we will ensure we are oriented to the challenges of progressive aphasia BB might be experiencing and brainstorm/consult with her on strategies we could use to better communicate with each other such as:

- Bringing her husband or another support person

- Booking for longer appointments so that conversations are not rushed

- Having a whiteboard available for her in clinic as an option

- Using a communication board with symbols as needed

- Speak slowly in simple, adult sentences and listen carefully.

In the initial stages, we will do community-based physical therapy two times per week focusing on improving functional abilities and balance. The goal of this initial stage is to improve B.B's. functional abilities so she can safely participate in exercise/physical activity outside of the clinic. Intervention plan in this stage will include primarily balance and lower extremity strength training. In addition, while lower extremity strength and balance are being worked on, we will give B.B. a single point cane. Based on B.B’s. Berg Balance Score and recent fall, we feel B.B. could use an assistive device to safely ambulate the community.

A functional training program was created in consultation with B.B. based on meaningful tasks she would like to improve upon. These tasks include: “Playing with grandchildren” and “grocery shopping”.

- Balance training: 30 seconds twice per day, 3 days per week.

- Progression from normal stance width → narrow base of support → tandem stance → single leg stance → standing with trunk rotation

- Balance training will be done on hard surfaces (tile or wood flooring) and transition to soft surfaces (carpet or even standing on a pillow).

- In clinic we will do perturbation based training. Including tossing/catching a ball and therapist delivered external perturbations.

- This will only be done in clinic for safety reasons.

- If BB is struggling, we may add mirror therapy to help her reflect on her positioning

- Lower extremity strength training: 10 reps, 2 sets, 2 minutes rest between sets, 2-3 days per week.

- ¼ squat (be done at a counter or table for balance support if needed)

- Sit to stand

- Knee to counters

- Step ups (beginning with the support of a railing and progressing to without)

- Lifting objects from the ground (progressing up to 10lbs)

- Gait training

- Interim education and training with a single point cane with a 2 point step through gait pattern.

- Gait training focused on functional community ambulation. We will focus on increasing gait speed, managing varying terrain, curbs and obstacles and walking in a distracting environment.

Throughout BB’s function training specific strategies will be used to enhance her learning and promote automaticity of movement. We will promote problem solving based learning by providing minimum guidance, knowledge of result feedback and promoting self-assessment. Other strategies we will use include:

- Tactile cuing

- Maintaining an external focus of attention

- Performing random practice with a high number of repetitions

Once balance deficits are improved upon, we will drop down to one physical therapy session biweekly to focus on maintaining function and monitoring disease progression. At this point B.B. can transition to exercise in the community. We will provide B.B. with extensive education about the benefits of regular physical activity on delaying disease progression and optimizing function. We would prescribe B.B. to engage in physical activity consistent with Canada’s Exercise Guidelines for Older Adults (>65). While the Canadian Alzheimer's Society simply recommends the guidelines for adults, we would use the ones for older adults since they include the addition of weekly balance training (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2022). These guidelines include:

- 150min moderate to vigorous physical activity, 2 days muscle/bone strengthening exercise per week plus weekly balance training (Government of Canada, 2019).

Once BB has progressed past basic strength and balance training, we will also implement the use of serious games technology. Serious games refers to any game that’s primary purpose is something other than entertainment. There are many different serious games which have shown to improve physical fitness, functional mobility, strength, and balance in older adults (Soares et al., 2016; Rossito et al., 2014). Additionally, they have also been shown to increase exercise compliance in older adults (Rossito et al., 2014). Current research has reflected the efficacy in treating balance deficits in dementia through use of serious games may have a more beneficial effect than medical treatment (Ning et al., 2020). Additionally, since participation in serious games promotes mental and physical exercise, literature has reflected the benefits in patients living with dementia to be greater than traditional exercise alone (Ning et al., 2020). Due to technology advances, there has become more options for serious games delivered through video games or virtual reality format that may be more engaging for patients (Ning et al., 2020) . There are various options available but finding one (or more) that B.B. enjoys is key. Some options include Wii Fit and Microsoft Kinect. Serious games using either a camera motion monitor (i.e. Microsoft Kinect) or a force sensor (i.e. Wii fit board) also allow for biofeedback via visual, tactile (vibrations), and audio means. An additional benefit of serious games is that they allow us to monitor progress over time and identify motor deficit progression.

The study conducted by Urturi Breton et al., showcases the use of a specific serious games intervention for patients living with dementia that presented promising results relating to patient motivation and cognitive stimulation. The intervention was called KiMentia and it promoted both mental and physical stimulation through presenting challenges to be completed on a screen while a kinetic sensor senses body movements that are required to complete the challenges (Urturi Breton et al., 2012). Various tasks are available to suit different levels of cognitive functioning in different patients. An example task was categorizing images of objects into locations where they are likely to be found while the pt has to move the answers on the screen to the correct locations through body movements (Urturi Breton et al., 2012). This type of intervention could be beneficial to B.B’s treatment plan as it will challenge her balance by the internal perturbations of body movements, and cognitively by the planning and organizing the objects into their correct categories.

In terms of continuing balance training in the community, we will advise B.B. to sign up for weekly Tai Chi class as she has expressed interest in beginning this physical activity. Tai chi has been shown to improve balance, reduce falls, and improve quality of life as well as short term cognitive function in dementia patients (Lim et al., 2019; Nyman et al., 2019).

We have chosen to transition B.B. to community-based exercise to promote independence and make B.B. a more active member of their community. We have also chosen to keep regular appointments to monitor B.B. as their disease progresses and adjust our treatment plan as needed. Ongoing assessment is crucial to B.B’s. success given the progressive nature of the disease. Additional resources that we will consider as disease progress include referral to a social worker for community aids for both B.B. and their family, and speech language pathology for assistance with their aphasia (see below).

Outcomes[edit | edit source]

After 4 weeks, objective measures were performed again to determine the improvements that were made after the various exercises and treatments were performed. The Berg Balance Scale was re-administered giving a score of 48/56. Her gait speed decreased to 0.69 m/s (MCID=0.13 m/s) as well as the TUG decreasing to 13.1 secs while the dual task TUG decreased to 27 secs. Her ABC scale score increased to 60 which indicates she is in the moderate level of confidence for patients. For the other cognitive tests, her mini-cog test score remained at a 1 while the MoCA score re-administered by the OT decreased to a 23/30. Her dysmetria has decreased as her coordination increased during the heel-shin test.

The changes in her MMTs after 4 weeks are listed in the chart below

| Muscle group | Right | Left |

| Shoulder Flexion | 4 | 4 |

| Shoulder Extension | 4 | 4 |

| Elbow Flexion | 4 | 4+ |

| Elbow Extension | 4 | 4+ |

| Hip Flexion | 4 | 4 |

| Hip Extension | 4 | 3+ |

| Knee Flexion | 3+ | 3+ |

| Knee Extension | 4 | 3+ |

Overall, these 4 weeks has helped her with her overall confidence and independence. She may still require some assistance in her BADLs and IADLs after discharge that her husband or son can help with. If they are unable to, then a personal support worker (PSW) may be referred to help her at home when needed. She will also still need referral/continued treatments to a speech-language pathologist to address her primary progressive aphasia. She also will need to be referred to a neuropsychologist to continually assess her cognition as the dementia progresses.

Interprofessional Interventions[edit | edit source]

Neurologist[edit | edit source]

A neurologist would play a crucial role in the long-term care of B.B as she copes with diagnosis and progresses through the stages of Vascular Dementia. This field of medicine is the relationship between the brain and the behavioural or cognitive presentation of an individual, with an emphasis on neurological disorders (Elsey et a.l, 2015). Since the cognitive losses caused by dementia are such a hallmark feature of the disease, proper assessment and treatment interventions are critical to optimizing function (Arvanitakis et al., 2020). A neurologist could conduct assessments to determine level of cognitive functioning while tracking the impact of disease progression on this level over time (Elsey et al., 2015). In addition to assessment, a neurologist may offer medical treatments to reduce symptoms as interventions that lie beyond the scope of physiotherapy (Elsey et al., 2015). Finally, a neurologist may also assess the efficacy of rehabilitation and medical strategies on function (Elsey et al., 2015). As reflected in this case study, the inclusion of neurology into B.B's health care offered critical importance to her correct diagnosis of Vascular Dementia through use of Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) Test, and the ordering and interpretation of imaging (Miki et al., 2012). A neuropsychologist could offer these assessments as well as continuous treatment interventions that target B.B's cognitive deficits relating to memory, concentration, planning and communication.

Occupational Therapist[edit | edit source]

Including an occupational therapist in B.B's treatment is important for therapeutic treatments to maintain skill or develop new strategies to complete activities of daily living. An occupational therapist would work in collaboration with B.B to determine areas in which her disease presentation is affecting her daily life and develop learning strategies to overcome or adapt to these effects while promoting independence (“therapeutic interventions,”,2022). Therapeutic interventions over the course of dementia progression can include; adapting home environment, graded assistance training in BADL/IADL performance and recommendation for assistive devices usage such as mobility aids (“therapeutic interventions,”,2022). Specific to B.B's case, at her current stage she is experiencing difficulties in performing her IADLs, especially in tasks requiring more balance. Therefore an Occupational Therapist can identify these activities of difficulties and build treatment interventions to improve independence her performance of such tasks (“therapeutic interventions,”,2022).

Speech Language Pathologist[edit | edit source]

Referral to a speech language pathologist would be beneficial as the profession focuses on the identification and treatment of speech/language disorders while emphasizing the relation between cognition and communication. Similar to other interprofessional health care fields, the focus of intervention is restorative or compensatory strategies for functional losses depending on patient presentations and stage of disease progression. A speech language pathologist will assess patients current level of functioning and design meaningful treatments to address primary concerns that may be adjusted through disease progression. For patient presentations such as B.B's discussed in the current case study, interventions may focus on improving cognitive communication through tasks related to problem solving, memory stimulation and thought organization.

Discussion[edit | edit source]

B.B. is a 60-year female who was initially diagnosed by a physician with Stage 3 Vascular Dementia Subcortical Subtype (also known as Binswanger’s Disease) and referred to an outpatient neurological rehabilitation centre. She was first admitted to a hospital due to a minor fall 2-weeks ago. Furthermore, it is believed by the PCP that B.B. had suffered a TIA within the past few months but went undiagnosed and untreated. Before present, B.B. was completely independent in all BADLs and IADLs despite living with a sedentary lifestyle and controlled hypertension.

As of late, B.B. has noticed a decrease in her abilities to perform ADLs independently, decreased confidence in balance and strength, and several symptoms of cognitive decline including (but not limited to) memory loss, psychomotor slowness and weakness, and difficulty organizing her thoughts. Although Vascular Dementia is incurable, it would be beneficial for the interprofessional team to manage and prevent complications.

Regarding problems amenable to physical therapy care, it is remarkably important to address B.B.’s lack of confidence in balance by improving balance, strengthening weak muscles that may contribute to impaired balance, and maintaining functional range of motion. Some problems that physiotherapists may not be able to treat but ought to keep in mind include B.B.’s memory impairments, unpredictable changes in mood, behaviour, and personality, and Primary Progressive Aphasia which may cause difficulty communicating with the patient.

Specific to B.B’s treatment plan, the physical therapists will provide her with community-based PT treatment two times per week, primarily focused on improving balance and functional abilities. Following Canada’s Exercise Guidelines for Older Adults (>65), there will be 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous aerobic exercise and two days of strengthening exercises each week in addition to balance training. Strategies employed to improve compliance include the use of serious games and activities that B.B. enjoys such as Tai-Chi.

*talk about pre- and post- outcome measures for this case!*

In conclusion, this case study demonstrates the challenges, impairments, and management interventions that can be used for patients with early stage Subcortical Vascular Dementia. The study also provides evidence of interventions and associated outcome measures that may be beneficial for this population. It is always important to understand problems within the scope of PT practice and when to refer out to other healthcare providers. Lastly, while this case study provides one way of providing treatment to this population, interprofessional teams ought to consider the context of each individual patient and their related goals.

Self-study Questions[edit | edit source]

1. Which of the following a common symptom in patients with Subcortical Vascular Dementia?

A) Psychomotor slowness

B) Memory impairments

C) Mood changes

D) Balance deficits

E) All of the above

2. Based on B.B.’s case, she received a score of 36/56 on the Berg Balance Scale, putting her at risk for falls. In order to improve her balance, what is the best evidence-based intervention that may benefit B.B.’s return to the community?

A) Mental imagery of balancing on one-leg

B) Tai-Chi

C) Tying her lower extremities together to challenge balance with narrower BOS

D) Sitting on a bed with no upper extremity support while the therapist adds external perturbations (e.g. shoves, lean and release, etc.)

3. Which of the following may NOT be an appropriate outcome measure for B.B.’s case in the initial assessment?

A) Community Balance and Mobility Scale (CBMS)

B) Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test

C) Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale (ABC)

D) 10-metre walk test

Answers: 1) E 2) B 3) A

References[edit | edit source]

Arvanitakis, Z., Shah, R.C., Bennett, D.A. (2020). Diagnosis and management in Dementia. JAMA, 322(16): 1589-1599. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.4782

Breton, Z. S., Zapirain, B. G., & Zorrilla, A. M. (2012). Kimentia: Kinect based tool to help cognitive stimulation for individuals with dementia. 2012 IEEE 14th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom). https://doi.org/10.1109/healthcom.2012.6379430

Canada, P. H. A. of. (2019, November 7). Government of Canada. Canada.ca. Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/physical-activity-tips-older-adults-65-years-older.html

Elsey, C., Drew, P., Jones, D., Blackburn, D., Wakefield, S., Harkness, K., Venneri, A., & Reuber, M. (2015). Towards diagnostic conversational profiles of patients presenting with dementia or functional memory disorders to memory clinics. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(9), 1071–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.021

Forbes, D., Thiessen, E. J., Blake, C. M., Forbes, S. S., & Forbes, S. (2014). Exercise programs for people with dementia. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 132, 195-196.

Hall, A. J., Burrows, L., Lang, I. A., Endacott, R., & Goodwin, V. A. (2018). Are physiotherapists employing person-centred care for people with dementia? an exploratory qualitative study examining the experiences of people with dementia and their carers. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0756-9

Lim, K. H. L., Pysklywec, A., Plante, M., & Demers, L. (2019). The effectiveness of Tai Chi for short-term cognitive function improvement in the early stages of dementia in the elderly: a systematic literature review. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 14, 827.

Miki, E., Kataoka, T., & Okamura, H. (2012). Clinical usefulness of the Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside (FAB) for elderly cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(3), 857–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1595-4

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2007). Therapeutic interventions for people with dementia: Cognitive symptoms and maintenance of functioning. Retrieved May, 13, 2019.

Ning, H., Li, R., Ye, X., Zhang, Y., & Liu, L. (2020). A review on serious games for dementia care in ageing societies. IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine, 8, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1109/jtehm.2020.2998055

Nyman, S. R., Ingram, W., Sanders, J., Thomas, P. W., Thomas, S., Vassallo, M., ... & Barrado-Martín, Y. (2019). Randomised controlled trial of the effect of Tai Chi on postural balance of people with dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 14, 2017.

Rolland, Y. (2012). Exercise and Dementia. Pathy's Principles and Practice of Geriatric Medicine, 1, 911-921.

Rossito¹, G. M., Berlim¹, T. L., da Silva Hounsell¹, M., Vinicius, A., & em Neuroreabilitação–NUPEN, N. D. P. (2014). SIRTET-K3D: a serious game for balance improvement on elderly people.

Soares, A. V., Júnior, N. B., Hounsell, M. S., Marcelino, E., Rossito, G. M., & Júnior, Y. S. (2016). A serious game developed for physical rehabilitation of frail elderly. European Research in Telemedicine/La Recherche Européenne en Télémédecine, 5(2), 45-53.

Staying physically active. Alzheimer Society of Canada. (n.d.). Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https://alzheimer.ca/en/help-support/im-living-dementia/living-well-dementia/staying-physically-active

Therapeutic interventions for people with dementia – cognitive symptoms ... (n.d.). Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55462/

Warrick, N., Prorok, J. C., & Seitz, D. (2018). Care of community-dwelling older adults with dementia and their caregivers. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 190(26). https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170920