Subacromial Pain Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div><div align="justify"> | </div><div align="justify"> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

There has been huge debate in relation to the diagnostic labelling of non-traumatic shoulder pain related to the structures of the subacromial space. The diagnostic label Subacromial Impingment Syndrome (SIS) was first introduced in 1972 by Dr Charles Neer and was based on the mechanism of structural impingement of the structures of the subacromial space, and as reflected by the literature is considered by many to be one of the most common causes of shoulder pain.<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":6">Cools AM, Michener LA. Shoulder Pain: Can One Label Satisfy Everyone and Everything? Br J Sports Med. 2017 Feb 16;51(5):416–7.</ref> SIS has been viewed as symptomatic irritation of the subacromial structures between the coraco-acromial arch and the humerus during<ref name=":5">de Witte PB Nagels J van Arkel ER, et al. Study protocol subacromial impingement syndrome: the identification of pathophysiologic mechanisms (SISTIM). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011; 12:1-12. </ref>, with Primary | There has been huge debate in relation to the diagnostic labelling of non-traumatic shoulder pain related to the structures of the subacromial space. The diagnostic label Subacromial Impingment Syndrome (SIS) was first introduced in 1972 by Dr Charles Neer and was based on the mechanism of structural impingement of the structures of the subacromial space, and as reflected by the literature is considered by many to be one of the most common causes of shoulder pain.<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":6">Cools AM, Michener LA. Shoulder Pain: Can One Label Satisfy Everyone and Everything? Br J Sports Med. 2017 Feb 16;51(5):416–7.</ref> [[File:Shapes of Acromion.jpg|thumb|463x463px|Figure 2. Acromion shapes.]]SIS has been viewed as symptomatic irritation of the subacromial structures between the coraco-acromial arch and the humerus during elevation of the arm above the head<ref name=":5">de Witte PB Nagels J van Arkel ER, et al. Study protocol subacromial impingement syndrome: the identification of pathophysiologic mechanisms (SISTIM). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011; 12:1-12. </ref>, associated with either Primary or Secondary Impingement. Primary Impingement related to structural changes that mechanically narrow the subacromial space such as; bony narrowing, bony malposition after a fracture of the greater tubercle, or an increase in the volume of the subacromial soft tissues.<ref>Neer CS. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:41–50.</ref><ref>Leroux J-L, Codine P, Thomas E, Pocholle M, Mailhe D, Blotman F. Isokinetic evaluation of rotational strength in normal shoulders and shoulders with impingement syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1994;304:108–115</ref><ref name="af" /><ref name=":0">Bigliani LU, Levine WN. Current concepts review: Subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1854–1868.</ref><ref>Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Clark JM, McQuade KJ, Gibb TD, Matsen FA. Translation of the humeral head on the glenoid with passive glenohumeral motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72-a:1334–1343.</ref><ref>Morrison DS, Greenbaum BS, Einhorn A. Shoulder impingement. Orthop Clin North Am. 2000;31:285–293</ref><ref>Nicholson GP, Goodman DA, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. The acromion: Morphologic condition and age-related changes. A study of 420 scapulas. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:1–11.</ref><ref>Lewis JS, Wright C, Green A. Subacromial impingement syndrome: The effect of changing posture on shoulder range of movement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:72–87.</ref><ref name="debie">DE BIE R.A., BASTIANENEN C.H.G. Effectiveness of individualized physiotherapy on pain and functioning compared to a standard exercise protocol in patients presenting with clinical signs of subacromial impingement syndrome. A randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2010 Jun 9; 11:114.Level of evicence: 1B</ref><ref name="page">Phil Page, PhD, PT, ATC, LAT, CSCS, FACSM, SHOULDER MUSCLE IMBALANCE AND SUBACROMIAL IMPINGEMENT SYNDROME IN OVERHEAD ATHLETES, int J sport phys. Ther., 2011</ref><ref name="coaches">http://www.sbcoachescollege.com/articles/UpperCrossSyndromeShPain.html</ref> Secondary Impingement, commonly seen in overhead athletes, related to abnormal scapulothoracic kinematics or functional disturbance in the centering of the humeral head, leading to an abnormal displacement of the center of rotation when the arm is elevated or when the arm is placed in end-range abduction and external rotation, thereby causing soft tissue entrapment.<ref name=":1">Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, et al.: Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis 1998; 57: 649–55.</ref><ref name=":10" /><ref name=":11" /><ref name=":0" /><ref name=":12" /><ref name=":13" /> | ||

This has remained the dominant theory for injury to structures within the subacromial space for the past 40 years, and has been the rationale to guide clinical tests, conservative treatment, surgical procedures and rehabilitation protocols,<ref name=":6" /> however the validity of this model of acromial impingement model has been challenged from both a theoretical and practical perspective.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":7" /><ref name=":8">Cuff A, Littlewood C. Subacromial Impingement Syndrome - What does this mean to and for the Patient? A Qualitative Study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. Elsevier Ltd; 2017 Oct 17;:1–14.</ref> | These definitions and descriptions of SIS are based on a hypothesis that acromial irritation leads to external abrasion of the bursa, rotator cuff or other structures within the subacromial space.<ref name=":7">Lewis J. Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Musculoskeletal Condition or a Clinical Illusion? Physical Therapy Reviews 2011;16:388-298.</ref> This has remained the dominant theory for injury to structures within the subacromial space for the past 40 years, and has been the rationale to guide clinical tests, conservative treatment, surgical procedures and rehabilitation protocols,<ref name=":6" /> however the validity of this model of acromial impingement model has been challenged from both a theoretical and practical perspective throughout the last decade, with suggestions that the use of SIS terminology can potentially contribute to negative expectations of physiotherapy and conservative treatment for patients, which may compromise outcome, often resulting in an increased incidence for surgery.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":6" /><ref name=":7" /><ref name=":8">Cuff A, Littlewood C. Subacromial Impingement Syndrome - What does this mean to and for the Patient? A Qualitative Study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. Elsevier Ltd; 2017 Oct 17;:1–14.</ref> | ||

The anatomical explanation as “impingement” of the rotator cuff is not sufcient to cover the pathology. “Subacromial pain syndrome”, SAPS, describes the condition better.<ref name=":9">Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O, Meskers C, Naber R, de Ruiter T, et al. Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Subacromial Pain Syndrome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2014 May 21;85(3):314–22.</ref> | The anatomical explanation as “impingement” of the rotator cuff is not sufcient to cover the pathology. “Subacromial pain syndrome”, SAPS, describes the condition better.<ref name=":9">Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O, Meskers C, Naber R, de Ruiter T, et al. Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Subacromial Pain Syndrome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2014 May 21;85(3):314–22.</ref> | ||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

== Etiology == | == Etiology == | ||

'''Secondary shoulder impingement''' is defined as a relative decrease in the subacromial space due to glenohumeral joint instability or abnormal scapulothoracic kinematics<ref name=":10">McClure PW, Michener LA, Karduna AR. Shoulder function and 3-dimensional scapular kinematics in people with and without shoulder impingement syndrome. Phys Ther. 2006;86:1075–1090.</ref>. Commonly seen in athletes engaging in overhead throwing activities<ref name=":11">Belling Sorensen AK, Jorgensen U. Secondary impingement in the shoulder. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:266–278.</ref>, secondary impingement occurs when the rotator cuff becomes impinged on the posterior-superior edge of the glenoid rim when the arm is placed in end-range abduction and external rotation<ref name=":0" />. This positioning becomes pathologic during excessive external rotation, anterior capsular instability, scapular muscle imbalances<ref name=":12">Lukasiewicz AC, McClure P, Michener L, Pratt N, Sennett B. Comparison of 3-dimensional scapular position and orientation between subjects with and without shoulder impingement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:574–583.</ref>, and/or upon repetitive overload of the rotator cuff musculature<ref name=":13">Belling Sorensen AK, Jorgensen U. Secondary impingement in the shoulder. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:266–278.</ref>. | |||

'''Secondary shoulder impingement''' is defined as a relative decrease in the subacromial space due to glenohumeral joint instability or abnormal scapulothoracic kinematics<ref>McClure PW, Michener LA, Karduna AR. Shoulder function and 3-dimensional scapular kinematics in people with and without shoulder impingement syndrome. Phys Ther. 2006;86:1075–1090.</ref>. Commonly seen in athletes engaging in overhead throwing activities<ref>Belling Sorensen AK, Jorgensen U. Secondary impingement in the shoulder. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:266–278.</ref>, secondary impingement occurs when the rotator cuff becomes impinged on the posterior-superior edge of the glenoid rim when the arm is placed in end-range abduction and external rotation<ref name=":0" />. This positioning becomes pathologic during excessive external rotation, anterior capsular instability, scapular muscle imbalances<ref>Lukasiewicz AC, McClure P, Michener L, Pratt N, Sennett B. Comparison of 3-dimensional scapular position and orientation between subjects with and without shoulder impingement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:574–583.</ref>, and/or upon repetitive overload of the rotator cuff musculature<ref>Belling Sorensen AK, Jorgensen U. Secondary impingement in the shoulder. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:266–278.</ref>. | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 17:40, 28 January 2018

Original Editor - David Drinkard, Dorien De Strijcker

Lead Editors Dorien De Strijcker, Naomi O'Reilly, David Drinkard, Els Van Haver, Mariam Hashem, Admin, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Florence Brachotte, Amanda Ager, Kai A. Sigel, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Yuli Borremans, Scott Buxton, WikiSysop, Wendy Walker, Robin Tacchetti, Lisa De Donder, Ewa Jaraczewska, Lucas Villalta, 127.0.0.1, Benjamin Desmedt, Tyler Shultz, Thaisa Van Bellingen, Wanda van Niekerk, Lauren Lopez, Lucinda hampton and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

There has been huge debate in relation to the diagnostic labelling of non-traumatic shoulder pain related to the structures of the subacromial space. The diagnostic label Subacromial Impingment Syndrome (SIS) was first introduced in 1972 by Dr Charles Neer and was based on the mechanism of structural impingement of the structures of the subacromial space, and as reflected by the literature is considered by many to be one of the most common causes of shoulder pain.[1][2] SIS has been viewed as symptomatic irritation of the subacromial structures between the coraco-acromial arch and the humerus during elevation of the arm above the head[1], associated with either Primary or Secondary Impingement. Primary Impingement related to structural changes that mechanically narrow the subacromial space such as; bony narrowing, bony malposition after a fracture of the greater tubercle, or an increase in the volume of the subacromial soft tissues.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] Secondary Impingement, commonly seen in overhead athletes, related to abnormal scapulothoracic kinematics or functional disturbance in the centering of the humeral head, leading to an abnormal displacement of the center of rotation when the arm is elevated or when the arm is placed in end-range abduction and external rotation, thereby causing soft tissue entrapment.[14][15][16][6][17][18]These definitions and descriptions of SIS are based on a hypothesis that acromial irritation leads to external abrasion of the bursa, rotator cuff or other structures within the subacromial space.[19] This has remained the dominant theory for injury to structures within the subacromial space for the past 40 years, and has been the rationale to guide clinical tests, conservative treatment, surgical procedures and rehabilitation protocols,[2] however the validity of this model of acromial impingement model has been challenged from both a theoretical and practical perspective throughout the last decade, with suggestions that the use of SIS terminology can potentially contribute to negative expectations of physiotherapy and conservative treatment for patients, which may compromise outcome, often resulting in an increased incidence for surgery.[20][2][19][20]

The anatomical explanation as “impingement” of the rotator cuff is not sufcient to cover the pathology. “Subacromial pain syndrome”, SAPS, describes the condition better.[21]

Definition / Description[edit | edit source]

Subacromial Pain Syndrome has been defined Diercks et al[21] as all non-traumatic, usually unilateral, shoulder problems that cause pain, localized around the acromion, often worsening during or subsequent to lifting of the arm.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

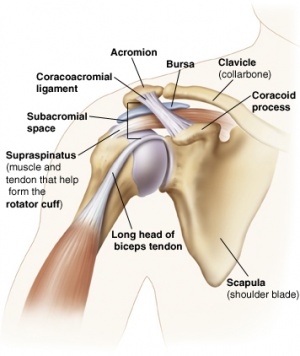

The Subacromial Joint Space is the space beneath the acromion (between the acromion and the top surface of the humeral head). This space is outlined by the acromion and the coracoid process (which are parts of the scapula), and the coraco-acromial ligament which connects the two. [24]

This space contains the;

- Coracoacromial Arch, composed of the Acromion, Coracoid Process and Coracoacromial Ligaments[5]

- Humerus

- Tendons of the Rotator Cuff; Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres Minor and Subscapularis

- Tendon of the Long Head of Biceps Brachii

- Subacromial Bursa[25]

- G-H Joint Capsule

Prevalence /Incidence[edit | edit source]

SIS is the most common disorder of the shoulder, accounting for 44% to 65% of all complaints of shoulder pain[26].The incidence increases as the population ages[27]. Peak incidence is during the sixth decade of life. The most common clinical diagnoses are rotator cuff defects (85%) and/or impingement syndromes (74%) [28]. The prevalence of rotator cuff defects rises with age. Up to 30% of persons over age 70 have a total defect, but 75% of such cases are asymptomatic[29].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Secondary shoulder impingement is defined as a relative decrease in the subacromial space due to glenohumeral joint instability or abnormal scapulothoracic kinematics[15]. Commonly seen in athletes engaging in overhead throwing activities[16], secondary impingement occurs when the rotator cuff becomes impinged on the posterior-superior edge of the glenoid rim when the arm is placed in end-range abduction and external rotation[6]. This positioning becomes pathologic during excessive external rotation, anterior capsular instability, scapular muscle imbalances[17], and/or upon repetitive overload of the rotator cuff musculature[18].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

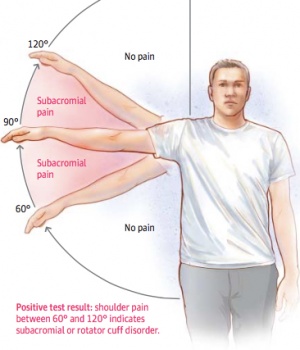

The affected patients are generally over age 40 and suffer from persistent pain without any known preceding trauma[31]. Patients report pain on elevating the arm between 70 ° and 120 ° ,the “painful arc” (Figure 3), on forced movement above the head, and when lying on the affected side [14]. The symptoms can be acute or chronic. Most of the time it is a gradual, degenerative condition that causes impingement, rather than due to a strong external force. Therefore, patients often have difficulties with determining the exact time of the complaints.

According to Neer impingement syndrome is divided into three stages:

- Stage I: moderate pain during exercise, no loss of strength and no limitation in movement. Edema and/or hemorrhage may be present. This stage generally occurs in patients less than 25 years of age and is frequently associated with an overuse injury. At this stage the syndrome could be possibly reversible. [32]

- Stage II: pain is usually reported during ADL and especially during the night. loss of mobility is associated with this stage. Stage II is more advanced and tends to occur in patients between 25 to 40 years of age. The pathological changes show fibrosis as well as irreversible tendon changes.[32]

- Stage III: strong restriction in movement due to calcifications and loss of muscle strength.This stage generally occurs in patients over 50 years of age and frequently involves a tendon rupture or tear.[32]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

There are a variety of shoulder conditions that can initially be confused with subacromial impingement [33]. A thorough physical examination should confirm SIS and exclude other conditions such as[34]:

- Rotator Cuff Tears (Partial / Full)

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

- Cervical Spondylosis

- Rotator Cuff Tendinitis

- Subluxating Shoulder

- Acromioclavicular Joint Arthritis

- Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder)

- Glenohumeral arthritis

- Paralysis of the Trapezius

- Calcific Tendinitis

- Acute / Chronic Inflammation of the Bursa Subacromialis

- Rotator Cuff Tear / Arthropathy

- Glenohumeral Instability

- Nerve Palsy

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

History and clinical examination are necessary[11]. Radiographs may be used to detect anatomical variants, calcific deposits or acromioclavicular joint arthritis. The three recommended views are[35]:

- Antero-posterior view with the arm at 30 degrees external rotation: The anteroposterior view is useful for assessing the glenohumeral joint, subacromial osteophytes and sclerosis of the greater tuberosity.

- Outlet Y view is useful because it shows the subacromial space and can differentiate the acromial processes.

- Axillary view is helpful in visualizing the acromion and the processus coracoideus, as well as coracoacromial ligament calcifications.

The size of the subacromial space can also be measured. MRI can show full or partial tears in the tendons of the rotator cuff, cracks in the capsule and inflammation to weak structures.[36]

Ultrasonography and arthrography are being used when rotator cuff tears are suspected or in complex cases. However, arthrography is invasive and expensive, it is the best diagnostic modality.[32]

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

Patient is diagnosed with SIS when these tests are positive:[37]

- Hawkins-Kennedy

- Neer impingement test

- Painful Arc (between 70° and 120°)

- Empty can (Jobe)

- External rotation resistance tests

- Drop arm sign: to test the integrity of the Infraspinatus.

- Patient elevates the arm and returns slowly. The test is positive when the patient has suddenly severe pain or the arm drops all of the suddenly.[38]

- Lift-off test (or gerber lift test): Integrity Subscapulary muscle. Patient performs an internal rotation by putting his hand on the ipsilateral buttock. Next the patient needs to lift the hand from the buttock against resistance.[38]

- The horizontal adduction test: arm is in adduction directed to the other shoulder and the elbow is flexed. If pain occurs, then the test is positive.

- Yergason test: Specific to bicipital tendonitis.

- Speed test

The most sensitive diagnostic tests are Hawkins test, Neer test, and the Horizontal Adduction test. While drop arm test, Yergason test and the speed test are the most specific tests.[39] The combination of the Hawkins-Kennedy test (testing the pain-ful arc) and the infraspinatus muscle test have a considerably higher predictive value (the higher the value, the better)[40]:

- 3 tests are positive: the probability that the patient has an impingement is (10,56)

- 2 tests are positive: the probability that the patient has an impingement is (5,03)

- 1 test is psitive: the probability that the patient has an impingement is (0,90)

- 0 tests are positive: the probability that the patient has an impingement is (0,17).

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment depends on age, activity level and general health of the patient. The goal is to reduce pain and regain function.Conservative treatment is used at the beginning, for several weeks to months until improvement and return tot function are noticed.[42]

Conservative treatment consists of :rest or avoiding overhead activities, NSAID’s to reduce pain and swelling, Physical therapy management, and steroid injection in case of failure of other interventions. Cortisone is often used because of its anti-inflammatory and pain reducing effect.[43]

Non-conservative treatment is recommended when the conservative treatments fail to reduce the pain.[44]

Treatment can be classified according to Neer's stages:

- Stage I is often treated conservatively. Pain can be relieved by applying ice (20 minutes, 3 times/day) and using NSAID’s (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). Physical therapy is also part of the treatment.

- Stage II: Surgical intervention is needed when the subacromial impingement lasts 3-6 months without significant improvement with appropriate conservative treatment.

- Stage III: may be indicated for surgery, especially when the passive range of motion of the patient is restricted. Surgery is also beneficial with type III acromion in combination with large spurs.[45]

Several surgical techniques are available, depending on the character and severity of the injury:

- Surgical Repair of torn tissues, mostly of supraspinatus muscle, long head of biceps tendon or joint capsule. Note: a rotator cuff tear is not an indication for surgery. [33]

- Bursectomy or removal of the subacromial bursa.

- Subacromial Decompression to increase the subacromial space by removing bony spurs or prominences on the underside of the os acromiale or the coracoacromial ligament

- Acromioplasty to increase the subacromial space by removing a part of the acromion. Arthroscopic acromioplasty is less invasive and requires lesser rehabilitation than the open (Neer) acromioplasty.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

There is strong evidence that supervised non-operative rehabilitation decreases pain in the shoulder and increases function.[25] Non-operative treatment should therefore be attempted first, assuming there is no tear that requires surgery.

Physical therapy management includes:

- RICE therapy in the acute phase to reduce pain and swelling

- Stability and postural correction exercises

- Mobility Exercises

- Strengthening Exercises

- Stretching exercises, including capsular stretching

- Manual therapy techniques of the shoulder

- Acupuncture

- Electrical stimulation

- Ultrasound and musculoskeletal ultrasound

- Low-level laser therapy has positive effects on all symptoms except on muscle strength[48]

When patient is presented with acute pain, it should be relieved first then strengthning exercises are implemented for prevention of future injuries. Although exercise therapy alone has proved efficient, the addition of manual therapy insures further increase in muscle strength.[49] Exercise therapy is a vital part of treatment for subacromial impingement but results showed no significant difference between home-based exercises and clinical exercise.

Strengthening exercises should include[50]:

- Rotator Cuff strengthening such as; external rotation with thera-tubing, Horizontal abduction exercises

- Lower and Middle Trapezius strengthening such as; Eated press up,Unilateral scapular rotation, Bilateral shoulder external rotation, Unilateral shoulder depression.

- Strengthening of the lower part of the trapezius muscle is an important part of exercise therapy. Individuals with impingement syndrome show greater ratios of upper and lower trapezius activity than asymptomatic individuals.[51]

Soft tissue mobilization to normalize muscle spasm and other soft tissue dysfunction has been shown to be effective alongside joint mobilizations to restore motion in treatment of SAI.[51]

The motions of the rotator cuff that are emphasized for strengthening are internal rotation, external rotation and abduction. It is important to remember that the function of the rotator cuff, in addition to generating torque, is to stabilize the glenohumeral joint. Thus, stronger rotator cuff muscles result in better glenohumeral joint stabilization and less impingement. A typical initial exercise program involves the use of 4 to 8 weights, with 10 to 40 repetitions performed three to five times a week.

Patients with Stage II impingement may require a formal physical therapy program. Isometric stretches are useful in restoring range of motion. Isotonic (fixed-weight) exercises are preferable to variable weight exercises. Thus, the shoulder exercises should be done with a fixed weight rather than a variable weight such as a rubber band. Repetitions are emphasized, and a relatively light weight is used. Sometimes, sports-specific techniques are useful, particularly for strengthening the throwing motion, the serving motion or swimming motions. In addition, physical therapy modalities such as electrogalvanic stimulation, ultrasound treatment and transverse friction massages can be helpful.[52]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Subacromial Pain Syndrome

- Is exercise effective for the management of subacromial impingement syndrome and other soft tissue injuries of the shoulder? A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

- Arthroscopic tuberoplasty for subacromial impingement secondary to proximal humeral malunionFailed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1VsHRGSo3HXVCiE3YsXdoVtjngMaV1dlFS8HD8_1UNglqkq9z: Error parsing XML for RSS

Presentations[edit | edit source]

Alice Thompson. Shoulder Impingement An insight into the Causes, Clinical Presentation, Assessment and Treatment of Shoulder Impingement. A Reference for Physiotherapists. 2012

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 de Witte PB Nagels J van Arkel ER, et al. Study protocol subacromial impingement syndrome: the identification of pathophysiologic mechanisms (SISTIM). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011; 12:1-12.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Cools AM, Michener LA. Shoulder Pain: Can One Label Satisfy Everyone and Everything? Br J Sports Med. 2017 Feb 16;51(5):416–7.

- ↑ Neer CS. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:41–50.

- ↑ Leroux J-L, Codine P, Thomas E, Pocholle M, Mailhe D, Blotman F. Isokinetic evaluation of rotational strength in normal shoulders and shoulders with impingement syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1994;304:108–115

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 KATCHINGWE AF, PHILLIPS B, SLETTEN E, PLUNKETT SW., Comparison of Manual Therapy Techniques with Therapeutic Exercise in the Treatment of Shoulder Impingement: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Clinical Trial. The Journal of Manual fckLRManipulative Therapy 2008;16(4): p238-¬‐247

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Bigliani LU, Levine WN. Current concepts review: Subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1854–1868.

- ↑ Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Clark JM, McQuade KJ, Gibb TD, Matsen FA. Translation of the humeral head on the glenoid with passive glenohumeral motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72-a:1334–1343.

- ↑ Morrison DS, Greenbaum BS, Einhorn A. Shoulder impingement. Orthop Clin North Am. 2000;31:285–293

- ↑ Nicholson GP, Goodman DA, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. The acromion: Morphologic condition and age-related changes. A study of 420 scapulas. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:1–11.

- ↑ Lewis JS, Wright C, Green A. Subacromial impingement syndrome: The effect of changing posture on shoulder range of movement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:72–87.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 DE BIE R.A., BASTIANENEN C.H.G. Effectiveness of individualized physiotherapy on pain and functioning compared to a standard exercise protocol in patients presenting with clinical signs of subacromial impingement syndrome. A randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2010 Jun 9; 11:114.Level of evicence: 1B

- ↑ Phil Page, PhD, PT, ATC, LAT, CSCS, FACSM, SHOULDER MUSCLE IMBALANCE AND SUBACROMIAL IMPINGEMENT SYNDROME IN OVERHEAD ATHLETES, int J sport phys. Ther., 2011

- ↑ http://www.sbcoachescollege.com/articles/UpperCrossSyndromeShPain.html

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, et al.: Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis 1998; 57: 649–55.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 McClure PW, Michener LA, Karduna AR. Shoulder function and 3-dimensional scapular kinematics in people with and without shoulder impingement syndrome. Phys Ther. 2006;86:1075–1090.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Belling Sorensen AK, Jorgensen U. Secondary impingement in the shoulder. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:266–278.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lukasiewicz AC, McClure P, Michener L, Pratt N, Sennett B. Comparison of 3-dimensional scapular position and orientation between subjects with and without shoulder impingement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:574–583.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Belling Sorensen AK, Jorgensen U. Secondary impingement in the shoulder. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:266–278.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Lewis J. Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Musculoskeletal Condition or a Clinical Illusion? Physical Therapy Reviews 2011;16:388-298.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Cuff A, Littlewood C. Subacromial Impingement Syndrome - What does this mean to and for the Patient? A Qualitative Study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. Elsevier Ltd; 2017 Oct 17;:1–14.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O, Meskers C, Naber R, de Ruiter T, et al. Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Subacromial Pain Syndrome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2014 May 21;85(3):314–22.

- ↑ Physiotutors. Subacromial Pain Syndrome Cluster | SAPS. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UErH4NUsDWQ [last accessed 30/12/17]

- ↑ Sports Congress. Subacromial Pain Syndrome and Scapular Dyskinesia - Sports Medicine Congress 2016. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hv5YLrIGdn8[last accessed 15/01/18]

- ↑ http://www.jointsurgery.in/shoulder-arthoscopy/anatomy-of-shoulder/

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 TATE A.R., MCCLURE P.W., YOUNG I.A., SALVATOR R., MICHENER L.A., Comprehensive impairment-based exercise and manual therapy intervention for patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a case series. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 2010; 40(8): p474-93 (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ Bhattacharyya R, Edwards K, Wallace AW. Does arthroscopic sub-acromial decompression really work for sub-acromial impingement syndrome: a cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:1.

- ↑ Randelli P, Randelli F, Ragone V, et al. Regenerative medicine in rotator cuff injuries. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:129515

- ↑ Ostor AJ, Richards CA, Prevost AT, Speed CA, Hazleman BL: Diagnosis and relation to general health of shoulder disorders presenting to primary care. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005; 44: 800–5.

- ↑ Hedtmann A: Weichteilerkrankungen der Schulter – Subakromialsyndrome. Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie up2date 2009; 4:85–106.

- ↑ subacromial impingement aetiology. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TcsJOLSYcHg

- ↑ Garving, C., Jakob, S., Bauer, I., Nadjar, R., & Brunner, U. H. (2017). Impingement Syndrome of the Shoulder, 765–777. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2017.0765

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 KHAN Y, NAGY MT, MALAL J, WASEEM M, The painful shoulder: shoulder impingement syndrome. Open Orthop J Sept 2013, 6(7): 347-51

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 https://www.aafp.org/afp/1998/0215/p667.html#sec-6

- ↑ Lockhart RD. Movements of the Normal Shoulder Joint and of a case with Trapezius Paralysis studied by Radiogram and Experiment in the Living. J Anat 1930; 64: 288-302

- ↑ Smith M, Sparkes V, Busse M, Enright S. Upper and Lower trapezius muscle activity in subjects with subacromial impingement symptoms: Is there imbalance and can taping change it? Physical Therapy in Sport. 2009:10, 45-50

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedshoulderdoc - ↑ MICHENER L.A., WALSWORTH M.K., DOUKAS W.C., MURPHY K.P. Reliability and Diagnostic Accuracy of 5 Physical Examination Tests and Combination of Tests for Subacromial Impingement. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2009 Nov; 90(11): 1898-903. Level of evicence: 1C

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 ALGUNAEE M, GALVIN R, FAHEY T, Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ach Phys Med Rehabil 2012, 93(2): 229-36

- ↑ Mustafe çalis, Kenen Akgun, murat Birtane, Ilhan Karacan,Havva çalis,Fikret Tüzün, diagnostic values of clinical diagnostic tests in subacromial impingement syndrome, Ann Rheum Dis 1999

- ↑ Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the different degrees of subacromial impingement syndrome by Hyung Bin Park, MD, Atsushj Yokoia, MD, PHD, Harpkeet S. Gill, MD, George El Rassi, MD, and Edward G. Mcfarland, MD. Level of evidence 1

- ↑ Is Your Shoulder Pain an Impingement? 4 Quick Tests You Can Try.Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9z_qu8vX5Y

- ↑ Rhon DI, Boyles RE, Cleland JA, Brown DL, A manual physical therapy approach versus subacromial corticosteroid injection for treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome: a protocol for a randomized clinical trial, BMJ Open 2011

- ↑ AKGUN K, BIRTANE M., AKARIMAK U., Is local subacromial corticosteroïd injection beneficial in subacromial impingement syndrome?, Clin Rheumatol 2004, 23(6): 496-500

- ↑ http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00032

- ↑ Differential Diagnosis between common shoulder conditions, Leeds Community Healthcare, NHS Trust: www.leedscommunityhealthcare.nhs.uk/msk

- ↑ Arthroscopic subacromial decompression - Dr Terry Hammond.dv Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YLdjvpxXgnU

- ↑ Shoulder Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression - Dr. Tony Jabbour Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLd9yBiK3RA

- ↑ YELDAN I., CETIN E., OZDINCLER A.R. The effectiveness of low-level laser therapy on shoulder function in subacromial impingement syndrome. Disability and rehabilitation. 2009; 31(11): 935–940 (Level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Bang MD, Deyle GD. Comparison of Supervised Exercise With and Without Manual Physical Therapy for Patients with Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 2000;30(3):126-137 (Level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Kuhn JE. Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: A systematic review and synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol. Journal fo Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2009;18:138-160 (Level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Smith M, Sparkes V, Busse M, Enright S. Upper and Lower trapezius muscle activity in subjects with subacromial impingement symptoms: Is there imbalance and can taping change it? Physical Therapy in Sport. 2009:10, 45-50 (Level of evidence 3b)

- ↑ MORRISON D.S., FROGAMENI AD, WOODWORTH P., Non-operative treatment of subacromial impingement syndrome?, J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997. 79(5): 732 (Level of evidence 2b)

- ↑ Manual strategy for the treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome by Ulf Pape/ look subtitles Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9No0i7Wb2Rk

- ↑ Top 3 Exercises for the Rotator Cuff (using Stretch Band) Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FkzYvxhgqQQ