Stretching

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Reem Ramadan, Kapil Narale, Admin, Rafet Irmak, Naomi O'Reilly, Shaimaa Eldib, Rachael Lowe, Kim Jackson, Mmadu-Okoli Chukwunonso Oluebube, Nupur Smit Shah, Ahmed M Diab, Ahmed Essam and Jonathan WongPurpose[edit | edit source]

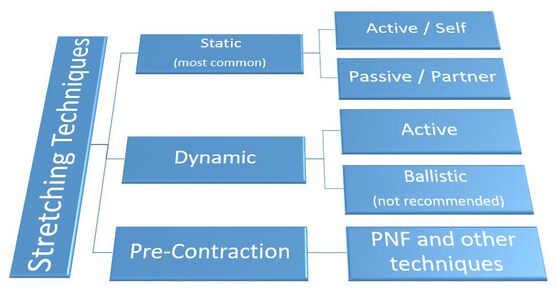

Stretching exercises have traditionally been included as part of a training and recovery program. Evidence shows that physical performance in terms of maximal strength, number of repetitions and total volume are all affected differently by the each form of stretching:

- Static stretch (SS),

- Dynamic stretch (DS)

- Pre-contraction stretching (Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation stretching (PNFS), the most common type of this type.[1][2]

Stretching can help improve flexibility and range of motion about your joints. Improved flexibility may: Improve your performance in physical activities; Decrease your risk of injuries; Help your joints move through their full range of motion; Enable your muscles to work most effectively[3]

This 4 minute video is a good summary of stretching.

The below video gives a brief description of the types of stretching ( isometric stretching here is similar to PNFS)

Static Stretching[edit | edit source]

Static stretching (SS) is a type of stretching exercises in which elongation of muscle with application of low force and long duration (usually 30 sec).Static stretching has a relaxation, elongation effect on muscle, improving range of motion (ROM),decreasing musculotendinous stiffness and also reduces the risk of acute muscle strain injuries.[5] It is a slow controlled movement with emphasis on postural awareness and body alignment. It is suitable for all patient types.[6]

Frequency and Duration of Static Stretching[edit | edit source]

To notice an improvement in range of motion, it is recommended, by research evidence that static stretches should be carried out in a higher-volume and higher frequency. It is not really about how long you hold a stretch, but more about how many times you do the stretch in a given day and week. It is recommended that a stretch of any single body part, should be held for a minimum total of 5 minutes per day. [7]

This can be broken down into five 1 minute sessions, or ten sessions of 30 seconds. The more frequent, and not necessarily a longer duration of hold, the better. [7]

It is seen that a stretching program of more than 3 weeks would be beneficial for decreasing muscle stiffness. [7]

Increasing stretching frequency, and therefore increasing overall time of stretching, will help to increase range of motion, and decrease muscle stiffness. [7]

It was shown that stretching for a duration of 2, 4, 6, or 8 minutes increased range of motion, but stretching for 10 minutes returned the range of motion back to baseline. [7]

Dynamic Stretching[edit | edit source]

Dynamic Stretching (DS) involves the performance of a controlled movement through the available ROM. Involves progressively increasing the ROM through successive movements till the end of the range is reached in a repetitive and progressive manner. Dynamic Stretching:

- Can be functional and mimic the movement of the activity or sport to be performed performed. eg a swimmer may circle their arms before getting into the water.

- Helps restore dynamic function and neuromuscular control through repeating and practicing movement thus enhancing motor control.

- Sometimes considered preferable to SS in the preparation for physical activity.[8]See Impact of Static Stretching on Performance

- Elevates core temperature increasing: nerve conduction velocity; muscle compliance and enzymatic cycling; and accelerating energy production.[1]

Though somewhat similar, dynamic stretching is different from Ballistic stretching. Dynamic stretching involves moving parts of your body and gradually increasing the range of motion and or speed of movement. In comparison, ballistic stretches involve trying to force a part of the body beyond its range of motion. In dynamic stretches, there are no bounces or 'jerky' movements. [9] Because of increased risk for injury, ballistic stretching is no longer recommended.[2]

Pre-Contraction Stretching: Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation Stretching (PNFS)[edit | edit source]

This form of stretching involves a contraction of the muscle being stretched or its antagonist before stretching. PNF is the most common type, see below. Other types of pre-contraction stretching include “post-isometric relaxation” (PIR). This type of technique uses a much smaller amount of muscle contraction (25%) followed by a stretch. Post-facilitation stretch (PFS) is a technique developed by Dr Vladimir Janda that involves a maximal contraction of the muscle at mid-range with a rapid movement to maximal length followed by a 15-second static stretch.

Multiple PNF stretching techniques exist, all of them rely on stretching a muscle to its limit. This triggers the inverse stretch reflex, a protective reflex that calms the muscle to prevent injury. Regardless of technique, PNF stretching can be used on most muscles in the body. PNFS can also be modified so you can do them alone or with a partner.[10]

The types of PNF stretch techniques are: Contract Relax (CR) Contraction of the muscle through its spiral-diagonal PNF pattern, followed by stretch; Hold Relax (HR) Contraction of the muscle through the rotational component of the PNF pattern, followed by stretch; Contract-Relax Agonist Contract (CRAC) Contraction of the muscle through its spiral-diagonal PNF pattern, followed by contraction of opposite muscle to stretch target muscle.

Mechanisms of Stretching[edit | edit source]

The stretching of a muscle fiber begins with the sarcomere, the basic unit of contraction in the muscle fiber. As the sarcomere contracts, the area of overlap between the thick and thin myofilaments increases. As it stretches, this area of overlap decreases, allowing the muscle fiber to elongate. Once the muscle fiber is at its maximum resting length (all the sarcomeres are fully stretched), additional stretching places force on the surrounding connective tissue. As the tension increases, the collagen fibers in the connective tissue align themselves along the same line of force as the tension. Therefor when you stretch, the muscle fiber is pulled out to its full length sarcomere by sarcomere, and then the connective tissue takes up the remaining slack. When this occurs, it helps to realign any disorganized fibers in the direction of the tension. This realignment is what helps in the rehabilitation of scarred tissue.[11]

The initial changes that are produced by stretch training involve mechanical adaptations that are followed by neural adaptations, which contrasts with the sequence observed during strength training.[12]

When a muscle is stretched, some of its fibers lengthen, but other fibers may remain at rest. The more fibers that are stretched, the greater the length developed by the stretched muscle.

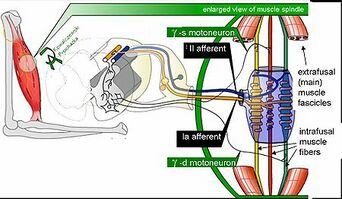

Proprioceptors: The proprioceptors related to stretching are located in the tendons and in the muscle fibers.

- Muscle Spindles (intrafusal fibers) lie parallel to the extrafusal fibers. Muscle spindles are the primary proprioceptors in the muscle.

- Another proprioceptor that comes into play during stretching is located in the tendon near the end of the muscle fiber and is called the golgi tendon organ.

- A third type of proprioceptor, called a pacinian corpuscle, is located close to the golgi tendon organ and is responsible for detecting changes in movement and pressure within the body[11].

The Stretch Reflex[edit | edit source]

When the muscle is stretched, so is the muscle spindle. The muscle spindle records the change in length (and how fast) and sends signals to the spine which convey this information. This triggers the stretch reflex which attempts to resist the change in muscle length by causing the stretched muscle to contract. The more sudden the change in muscle length, the stronger the muscle contractions will be (plyometric training is based on this fact). This basic function of the muscle spindle helps to maintain muscle tone and to protect the body from injury. One of the reasons for holding a stretch for a prolonged period of time is that as you hold the muscle in a stretched position, the muscle spindle habituates and reduces its signalling. Gradually, you can train your stretch receptors to allow greater lengthening of the muscles[11].

The below 5 minute video provides an explanation on the stretch mechanism:

Indications[edit | edit source]

Indications for stretching include:

- Improve joint ROM

- Increase extensibility of muscle tendon unit and periarticular connective tissue

- Return normal neuromuscular balance between muscle groups

- Reduce compression on joint surfaces

- Reduce injuries

- May be used prior to and after vigorous exercise to potentially reduce post-exercise muscle soreness[13]

Contraindications[edit | edit source]

Contraindications for stretching include:

- Joint motion limited by bony blocks

- After fracture and before bone healing is complete

- Acute inflammatory or infectious process

- When disruption of soft tissue healing is likely

- Sharp, acute pain with joint movement or muscle elongation

- Hematoma or other soft tissue trauma

- Hypermobility exists [13]

Determinants of Stretching[edit | edit source]

- Alignment: The position of the patient has to be comfortable and should be such that the stretch force is applied on the particular muscle.

- Stabilization: The bony segment of the muscle to be stretched, should be fixed appropriately.

- Intensity: It is the magnitude of the stretch applied.

- Duration: Total time of the stretch which is to be applied.

- Speed: The rate at which initial stretch is applied.

- Frequency: Total number of stretching sessions per day or per week.

- Mode of Stretch: This is the type of stretch. Static, ballistic or cyclic, the amount of participation of the client (active or passive) and the source of the stretch ( manual/mechanical/self)[14]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

When it comes to contractures, stiffening of soft tissues or muscles, it is seen that there is poor evidence for stretching as a treatment for contractures. In studies conducted of short term stretching durations (4-8 weeks) and frequency of stretch, it is seen that the impact of stretch only has a beneficial effect for a few minutes. [15]

There seems to be high quality evidence which shows that stretch doe snot have a clinically significant effect on joint mobility, in individuals with or without neurological conditions, despite the duration of stretch application each day. [15]

Moderate to high quality evidence also exists which shows that stretch doesn't have any effect on pain or quality of life in individuals with non-neurological conditions. [15]

Overall, a Cochrane systematic review determined that stretch is not effective for the management of contractures in individuals with or without neurological conditions, carried out in a short-term program. [15]

However, some practices are quite different than the presented evidence. Individuals with spinal cord injuries are frequently prescribed 1 hour of stretching on a permanent basis, to prevent or treat contractures. Considering such cases, it is very possible and likely that stretching may have an effect when carried out for extended periods of time, greater than 7 months, [15] especually when it contains a static component. [16]

From another study conducted on the stretch response of dorsiflexors, it was fund that static stretching and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF), as described above, has an effect in increasing dorsiflexion range of motion. [16]

Another view, which may be more conventional in practice is as follows:

A 2012 study on the evidence surrounding stretching techniques found that the benefits of stretching seem to be individual to the population studied. To increase ROM, all types of stretching are effective, although PNF-type stretching may be more effective for immediate gains. To avoid decrease in strength and performance that may occur in athletes due to static stretching before competition or activity, dynamic stretching is recommended for warm-up. Adults over 65 years old should incorporate static stretching into an exercise regimen. A variety of orthopedic patients can benefit from both static and pre-contraction stretching.[2]

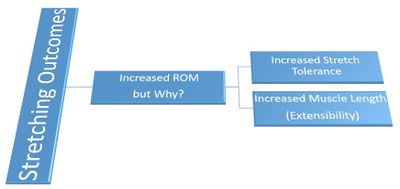

Outcome[edit | edit source]

Increased ROM as a result of stretching exercises can be a result of patients/athletes ability to withstand more stretching force or a real increase in muscle length [2]."İncreased stretch tolerance" term is used for ability to withstand more stretching force. Increased muscle length or increased extensibility terms are used for real increase in muscle length. Measurement of passive ROM is not sufficient to measure extensibility. Passive ROM should be measured with reference loads to identify increased stretch tolerance and increased extensibility.

Final Words[edit | edit source]

- To increase joint range of motion all types of stretching are effective, PNF-type stretching may be more effective for immediate gains.

- Dynamic stretching is recommended for warm-up for athletes before competition or activity.As static stretching will likely decrease strength and may influence performance.[17]

- Post exercise static stretching or Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation stretching is recommended for reducing muscle injuries and increasing joint range of motion.[18] Although Stretching has not been shown to be effective at reducing the incidence of overall injuries.

- Stretching is often included in Physiotherapy interventions for management of many kinds of clinical injuries. Despite positive outcomes, it is difficult to isolate the effectiveness of the stretching component of the total treatment plan because the protocols usually include strengthening and other interventions in addition to stretching.[1]

- Despite stretching not having strong evidence in research, it is highly sought by Physiotherapists for an effective long-term treatment modality. [15]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 POGO An evidence based guide to stretching Available from: https://www.pogophysio.com.au/blog/performance-maximisation/ (last accessed 1.6.2019)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Page P. Current concepts in muscle stretching for exercise and rehabilitation. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2012 Feb;7(1):109. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3273886/ (last accessed 1.6.2019)

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Stretching Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/fitness/in-depth/stretching/art-20047931 (last accessed 1.6.2019)

- ↑ Rachael Goepper Types of stretching Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3V_L7ArBn_A (last accessed 1.6.2019)

- ↑ Physiopedia Impact of static stretching on muscle performance Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Impact_of_Static_Stretching_on_Performance (last accessed 1.6.2019)

- ↑ Kay AD, Blazevich AJ. Effect of acute static stretch on maximal muscle performance: a systematic review. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise®. 2012 Jan 1;44(1):154-64. Available from: https://insights.ovid.com/medicine-science-sports-exercise/mespex/2012/01/000/effect-acute-static-stretch-maximal-muscle/20/00005768 (last accessed 3.6.2019)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Nakamura Masatoshi, Sato Shigeru, Hiraizumi Kakeru, Kiyono Ryosuki, Fukaya Taizan, Nishishita Satoru. Effects of static stretching programs performed at different volume-equated weekly frequencies on passive properties of muscle–tendon unit. Journal of Biomechanics. 2020:103:1-5.

- ↑ Mason D Exercise in rehabilitation In: Porter S Tidy's Physiotherapy Sydney Elsevier 2013 pages 281-284

- ↑ Top end sports Dynamic stretching Available:https://www.topendsports.com/medicine/stretching-dynamic.htm (accessed 26.12.2021)

- ↑ Healthline PNF stretching Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/fitness-exercise/pnf-stretching#pnf-techniques (last accessed 1.6.2019)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Appleton B. Stretching and Flexibility Everything you never wanted to know. World. 1998:68. Available: https://3yryua3n3eu3i4gih2iopzph-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/pdf/stretching.pdf(accessed 26.12.2021)

- ↑ Guissard N, Duchateau J. Neural aspects of muscle stretching. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2006 Oct 1;34(4):154-8. Available:https://journals.lww.com/acsm-essr/Fulltext/2006/10000/Neural_Aspects_of_Muscle_Stretching.3.aspx (accessed 26.12.2021)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Quizlet Purposes, Indications and Contradications of Stretching Exercises Available :https://quizlet.com/121027822/purposes-indications-and-contradications-of-stretching-exercises-flash-cards/ (accessed 26.12.2021)

- ↑ Kisner C, Colby LA, Borstad J. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques. Fa Davis; 2017 Oct 18.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Harvey Lisa A, Katalinic Owen M, Herbert Robert D, Moseley Anne M, Lannin Natasha A, Schurr Karl. Stretch for the treatment and prevention of contracture: an abridged Republication of a Cochrane Systematic Review. Journal of Physiotherapy. 63:2017:67–75.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Medeiros Diulian Muniz, Martini Tamara Fenner. Chronic effect of different types of stretching on ankle dorsiflexion range of motion: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The Foot. 34:2018:28–35.

- ↑ Shrier I. Does stretching improve performance?: a systematic and critical review of the literature. Clinical Journal of sport medicine. 2004 Sep 1;14(5):267-73. Available from: https://insights.ovid.com/clinical-sport-medicine/cjspm/2004/09/000/does-stretching-improve-performance-systematic/4/00042752 (last accessed 3.6.2019)

- ↑ Sharman MJ, Cresswell AG, Riek S. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching. Sports medicine. 2006 Nov 1;36(11):929-39. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17052131 (last accessed 3.6.2019)