Neck Pain: Clinical Practice Guidelines

Original Editors - Chad Adams, Jacob Melnick, & Tyler Shultz

Lead Editors Tyler Shultz, Kim Jackson, Angeliki Chorti, Cindy John-Chu, Eric Robertson, Alexandra Malzer, Dorian Mars, Admin, Jacob Melnick, Evan Thomas, Zachary Cooper, Scott Buxton, WikiSysop, Albert Alabaster, Tony Lowe, Nupur Smit Shah, Chad Adams, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Agoro Bukola Zainab and Rachael Lowe

Discussion & Background[edit | edit source]

The purpose of these clinical guidelines is to describe the new evidence based physical therapy practices including pathoanatomical features, examination, diagnosis/classification, intervention and treatment recommendations for musculoskeletal disorders related to neck pain. In 2017, The Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) revised the previous clinical practice guidelines of neck pain from 2008 and produced a new summary of recommendations and guidelines from current peer-reviewed literature[1].

Neck pain lacks a common clinical definition[2]. The most common type is non-specific neck pain defined as ‘’pain with a postural or mechanical basis, often called cervical spondylosis’’[3]. The 7 most common types of neck pain are: muscle pain, muscle spasm, headache, facet joint pain, nerve pain, referred pain and bone pain each with their own causation, diagnosis and treatment[4]. Neck pain is becoming increasingly common throughout the world[5] with around two thirds of people experiencing neck pain at one moment in their life. The prevalence of neck pain varies largely between studies with a ‘’mean point prevalence of 7.6% and mean lifetime prevalence of 48.5%’’[3]. Most studies indicate a higher incidence of neck pain among women[5], if you suffer from anxiety or depression[6] and if you are an office worker with poor position of the screen and keyboard[7].

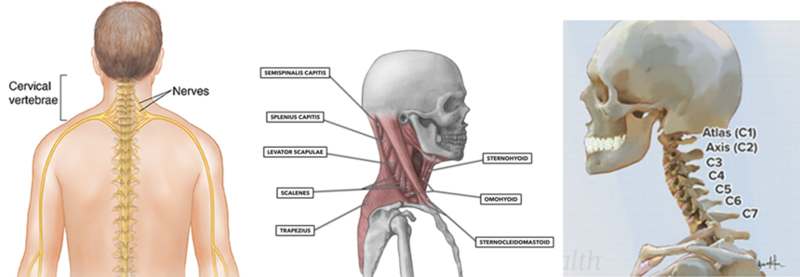

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Bones and Joints- The neck consists of 7 bones C1-C7. The most common neck pain caused by problems to the bone is osteoarthritis with wear in cartilage between the joints causing the bones to rub together producing pain and stiffness[8]. These bones are linked together by facet joints which are small joints between your vertebrae.

Muscles, Tendons and Ligaments- Large muscles of the neck such as the sternocleidomastoid and the trapezius enable gross motor movements in the neck. The most common pain produced by these structures is a neck strain which affects the cervical muscles and tendons or a sprain which affects the ligaments, both involving overstretching or tearing these structures.

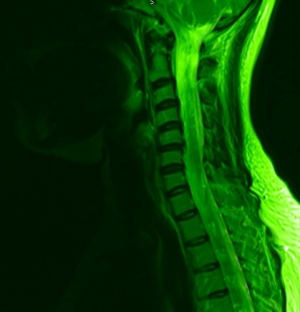

Nerves- Cervical spine nerves provide functional control and sensation to different parts of the body based on the spinal level at which they sit. There are 8 cervical nerves: C1,C2 and C3 help control the head and neck, including movements forward, backward, and to the sides[9]. C4 helps to control upward shoulder movement and helps to power the diaphragm, C5 helps to control the deltoids and the biceps . C6 helps to control the wrist extensors and provides some innervation to the biceps[10], C7 helps control the triceps and wrist extensors and finally C8 helps control the hands, such as finger flexion[9][10]. Pain can be caused when a nerve branching away from the spinal cord is compressed or irritated and sensation such as tingling is often felt in the upper extremities aiding identification of the damaged nerve.

Diagnoses/Causes[edit | edit source]

The neck is responsible for supporting the weight for the head and is flexible to allow rotation, flexion, extension and lateral flexion to occur. The neck is also vulnerable to conditions that cause pain and restrict motion. There are a variety of causes that can contribute to neck pain, these include[11];

- Muscle strains. The most common cause of neck pain. Neck strains are caused by overuse of the neck muscles such as too many hours sat hunched in a chair.

- Weakness. Training the upper traps more than the lower and mid traps may lead to overstimulation of the upper traps resulting in neck pain.

- Worn joints. As we age our joints in the neck become worn down. Osteoarthritis causes the cartilage between vertebrae to deteriorate. This can then cause osteophytes to form that can affect range of motion and cause pain.

- Nerve compression. Herniated disks or osteophytes in the vertebrae of your neck can press on the nerves branching out from the intervertebral foramen.

- Injuries. Motor collisions and sporting injuries can often result in whiplash injury, which occurs when the head is jerked backward and then forward, straining the soft tissues of the neck.

- Diseases. Diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, meningitis or cancer, can cause neck pain.

Eliminating the Red flags[edit | edit source]

Clinicians should ensure that they carry out thorough subjective screening for patients who present with neck pain. Subjective assessments should be used to eliminate possible red flags or serious pathology such as[12];

- Fractures

- Instability of the vertebrae

- Coronary Artery Dysfunction (CAD)

- Myelopathy

- Cancer

- Infection

- Visceral disorders

- Clinicians should also consider eliminating the 5 D 3 N red flags to rule out potential myelopathy.

- Dizziness

- Diplopia (double vision)

- Drop attacks

- Dysphagia (swallowing difficulties)

- Dysarthria (problems with speech)

- Nystagmus (involuntary eye movements)

- Nausea

- Neurological symptoms

Clinicians should use limitation of motion in the cervical and upper thoracic regions, presence of cervical pain related headache, history of trauma, and referred or radiating pain into an upper extremity as useful clinical findings for classifying a patient with neck pain into the following categories[1]:

- Neck pain with mobility deficits

- Neck pain with movement coordination impairments

- Neck pain with headaches

- Neck pain with radiating pain

Neck Pain with Mobility Deficits

- Cervical active range of movement verses passive range of movement in all planes of motion

Interventions: Neck Pain with Movement Coordination Impairments

- Neck and eye movements coordinated task

- Deep neck flexor test

Interventions: Neck Pain with Headaches

- Cervical deep neck flexor test

- Cervical range of movement test in all planes of motion

Interventions: Neck Pain with Radiating Pain[13]

The following tests can be used to determine if the patient has cervical radiculopathy

- Sterling’s test; This test has a sensitivity of 50 and a specificity of 88.

- Upper limb tension test. This test has a sensitivity of 50 and specificity of 86

- Cranial distraction test. This test has a sensitivity of 48 and a specificity of 98

When all of these clinical features are present, the post-test probability of cervical radiculopathy is 90%

Differential Diagnosis of patients with neck pain

If a patient’s impairments fall outside of the ranges of the classification system or the interventions do not fail to improve the symptoms, the clinician should consider serious pathological conditions or psychosocial factors as being possible explanations to the patient’s pain.

Examination Recommendations[edit | edit source]

The use of Outcome Measures (Grade: A)

Outcome tools can be used for evaluations, monitoring change over time, diagnosis and prognosis of neck pain. Validated self-report questionnaires should be used with patients complaining of neck pain. The Neck Disability Index and the Patient Specific Functional Scale are two examples of these questionnaires. The main reason for this recommendation is that these tools establish a baseline status for pain, function, and disability that can be used later in intervention selection and goal tracking.

Easily reproducible measures for activity and participation limitations related to neck pain should be used (Grade: F). This is to assess the change in function throughout the episode of care. An example of a tool to carry this out is the spinal function sort tool which like many other measures are more specific to low back pain and is part of the reasons for this recommendation being grade F. A study reports that the modified spinal function sort tool has good reliability and validity for assessing perceived self efficacy of work related tasks and the authors recommend this for patients with chronic musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders[14].

The consideration of certain risk factors that can predispose a patient to chronic neck pain (Grade: B)

On the first instance treating a patient with acute neck pain it may be useful to consider if the patient has any risk factors for developing chronic neck pain. Early detection of risk factors can allow the clinician to implement strategies to decrease the likelihood of developing chronic pain[15]. These risk factors include:

- Female

- History of neck pain

- High job demands

- Smoking

- Low social/work support

- History of low back pain

- Older age

- Depressed mood

- High role conflict

- Perceived muscular tension

Physical Impairment Measures (Grade: B)

Physical examination should be undertaken to establish baselines and monitor changes over time. Physical assessments can also be useful in the ruling in/out of conditions/causes of neck pain. Algometric assessment of pressure pain threshold should be used for classifying pain. Below are examination recommendations for different types of neck pain patients.

- Neck pain with mobility deficits: Cervical active ROM, the cervical flexion-rotation test and thoracic segmental mobility tests.

- Neck pain with headache: Cervical active ROM, the cervical flexion-rotation test and upper cervical segmental mobility testing.

- Neck pain with radiating pain: Neurodynamic testing, Spurling’s test, the distraction test and Valsalva test.

- Neck pain with movement coordination impairments: Cranial cervical flexion test and neck flexor muscle endurance test.

Patient Classification (Grade: C)

From examination, clinicians should categorise neck pain patients into one of the four previously mentioned groups in order to deliver the most appropriate treatment plan. To group patients, the clinician should carry out an appropriate subjective and objective examination. Below are the key findings to assess when placing patients into these categories. However, the classifications outlined are not exhaustive and therefore designating patients requires individual clinical judgement based on the examination findings.

Neck pain with mobility deficits:

- Central and/or unilateral neck pain

- Limitation in neck motion that consistently reproduces symptoms

- Associated (referred) shoulder girdle or upper extremity pain may be present

- Limited cervical ROM

- Neck pain reproduced at end ranges of active and passive motions

- Restricted cervical and thoracic segmental mobility

- Intersegmental mobility testing reveals characteristic restriction

- Neck and referred pain reproduced with provocation of the involved cervical or upper thoracic segments or cervical musculature

- Deficits in cervicoscapulothoracic strength and motor control may be present in individuals with subacute or chronic neck pain

Neck pain with movement coordination impairments (including Whiplash Associated Disorders):

- Mechanism of onset linked to trauma or whiplash

- Associated (referred) shoulder girdle or upper extremity pain

- Associated varied nonspecific concussive signs and symptoms

- Dizziness/nausea

- Headache, concentration, or memory difficulties; confusion; hypersensitivity to mechanical, thermal, acoustic, odor, or light stimuli; heightened affective distress

- Positive craniocervical flexion test

- Positive neck flexor muscle endurance test

- Positive pressure algometry

- Strength and endurance deficits of the neck muscles

- Neck pain with mid-range motion that worsens with end-range positions

- Point tenderness may include myofascial trigger points

- Sensorimotor impairment may include altered muscle activation patterns, proprioceptive deficit, postural balance or control

- Neck and referred pain reproduced by provocation of the involved cervical segments

Neck pain with headaches (cervicogenic headaches)

- Non-continuous, unilateral neck pain and associated (referred) headache

- Headache is precipitated or aggravated by neck movements or sustained positions/postures

- Positive cervical flexion rotation test

- Headache reproduced with provocation of the involved upper cervical segments

- Limited cervical ROM

- Restricted upper cervical segmental mobility

- Strength, endurance, and coordination deficits of the neck muscle

Neck pain with radiating pain (radicular)

- Neck pain with radiating (narrow band of lancinating) pain in the involved extremity

- Upper extremity dermatomal paresthesia or numbness, and myotomal muscle weakness

- Neck and neck-related radiating pain reproduced or relieved with radiculopathy testing: positive test cluster includes upper-limb nerve mobility, Spurling’s test, cervical distraction, cervical ROM

- May have upper extremity sensory, strength, or reflex deficits associated with the involved nerve roots

Intervention & Treatment Recommendations[edit | edit source]

Interventions: Neck Pain with Mobility Deficits[1]

Acute

Acute neck pain with mobility deficits can be managed in a variety of different ways. Recommended interventions include: thoracic manipulations, neck ROM exercises (such as movement through restricted range with increases in range to progress), scapulothoracic and UL and upper extremity strengthening, and cervical manipulation and/or mobilisation (such as AP glide of cervical spine).

Practitioners should also aim to enhance program adherence, which has been shown to improve with the inclusion of thoracic manipulation, neck ROM exercises and scapulothoracic and Upper extremity strengthening.

Subacute

For subacute management of neck pain with mobility deficits the following has been advised: neck and shoulder girdle endurance exercises (e.g. chin tuck endurance exercises. With gravity, against gravity, etc.), thoracic manipulation, and cervical manipulation and/or cervical mobilisation.

Chronic

Chronic neck pain with mobility deficits benefit more from a multimodal management technique, to include: thoracic manipulation and cervical manipulation or mobilisation; mixed exercises for cervical/scapulothoracic regions: neuromuscular exercise (e.g. coordination, proprioception, and postural training), stretching, strengthening, endurance training, aerobic conditioning, and cognitive affective elements; or intermittent mechanical/manual traction.

Dry needling can also be used as an intervention. It has been shown to be effective in short-term and long-term follow-ups when measuring its effect on: pain intensity, mechanical hyperalgesia, neck active range of motion, neck muscle strength, and perceived neck disability[16].

Low-effect laser therapy can provide relief from chronic neck pain for 2-6 months, with no serious side effects or complications being reported[17].

Furthermore, patient education should be provided in order to recommend an active lifestyle and address cognitive and affective factors – e.g. help to arrange a suitable weekly activity schedule.

Lastly, neck, shoulder girdle and trunk endurance exercises should be used – e.g. plank, side plank, shoulder shrugs, etc.

Interventions: Neck Pain with Movement Coordination Impairments[1]

Acute

Acute management of neck pain with movement coordination impairments should be managed with a strong focus on education, to include: return to nonprovocative pre-accident activities as soon as they are able to; minimise use of cervical collar; encourage postural and mobility exercises to decrease pain and increase ROM; reassure the patient of average recovery times of up to 2-3 months

Furthermore, a multimodal approach is favoured, to include: manual mobilisation techniques alongside exercise (e.g. strengthening, endurance, flexibility, postural, coordination, aerobic, and functional exercises).

If a patient is at low risk of progressing towards chronicity then the intervention applied should be focused around patient independence and involvement through education and a home exercise programme (HEP): a single session consisting of early advice, exercise instruction, and education; along with a comprehensive exercise program (to include strength and/or endurance with/without coordination exercises); and Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

It has been found that an effective HEP has a strong correlation with reduced neck pain, increased function, decreased disability and improved QoL[18]. Specifically, HEPs were more effective when they utilised self-mobilisation techniques, strengthening exercises, endurance exercises, and when the HEPs were designed to address a specific spinal level.

The current research on TENS in relation to neck pain is fairly sparse. Although effects have been seen, they have been limited to short-term effects, that usually recur; and show no sign of responding to treatment in the long-term. It’s also been shown that TENS is more effective than placebo, and seems to have an effect in reducing the intensity of acute and chronic cervical pain[19][20].

Patients who are showing signs of progressing towards chronicity or delayed rehabilitation outcomes should be identified and monitored as early as possible, in order to provide them with a more intensive rehabilitation and an early pain education program.

Chronic

Management of Chronic Neck Pain with Movement Coordination Impairments follows a similar emphasis on education and advice, focusing on assurance, encouragement, prognosis, and pain management.

Furthermore, mobilisation combined with an individualised, progressive submaximal exercise program including cervicothoracic strengthening, endurance, flexibility, and coordination, using principles of cognitive behavioural therapy is advised. This can be used alongside TENS.

Interventions: Neck Pain with Headaches[1]

Acute

For management of acute neck pain with headaches, an emphasis should be mainly placed on mobilisation.

Active mobility exercises should be provided along with supervised instruction to be given by the practitioner.

Furthermore, C1-C2 self-sustained natural apophyseal glide (self-SNAG) exercises should also be provided to be completed independently.

C1-C2 self-sustained natural apophyseal glide rotation exercises have shown improved results when combined with C1-C2 self-SNAG exercises, in comparison to C1-C2 self-SNAG exercises alone. This presented as a strong effect on pain intensity, physical function, CFRT and pain catastrophising. Furthermore, moderate improvements were seen in active Cervical range of movement, kinesiophobia and fear-avoidance beliefs[21].

Subacute

Subacute neck pain with headaches should also be managed with an emphasis on mobilisation, both independent and passively employed by a practitioner. This is to include:

- cervical manipulation and mobilization.

- C1–2 self-SNAG exercise and/or C1-2 SNAG rotation exercises

Chronic

Chronic neck pain with headaches should be managed through an intervention of cervical or cervicothoracic manipulation or mobilisations. This can be paired with shoulder girdle and neck stretching, alongside strengthening and endurance exercises for the shoulder girdle and neck.

migrainecanada.org - headache and neck pain is it possible that nerve compression is to blame

Interventions: Neck Pain with Radiating Pain[1]

Acute

Acute management of neck pain with radiating pain focuses on a few different modalities. One intervention available to practitioners is mobilising and stabilising exercises.

Another intervention available to practitioners for acute management of neck pain with radiating pain, is laser intervention.

Finally, practitioners may employ use of a cervical collar, but only in the short-term.

Chronic

Management of chronic neck pain with radiating pain, completely differs from acute management.

Mechanical intermittent cervical traction can be used as an intervention in chronic patients, in conjunction with stretching and strengthening exercises, and cervical and thoracic mobilisation and/or manipulation.

Traction should be used in conjunction with other interventions, because on its own it has found limited success. It has been shown that traction has no specific benefits as an intervention for chronic neck pain in adults when compared to standard physiotherapy interventions[22]. However, the research suggests exercise as a more relevant therapeutic management strategy.

Alongside other interventions, education and counselling to encourage participation in exercises and occupational activities are recommended.

Further advice (NICE, 2018):

Acute:

· For people with acute neck pain (lasting less than 6 weeks) or subacute neck pain (lasting for 6–12 weeks):

- Provide reassurance — neck pain is a common problem that usually resolves within a few weeks.

- Offer oral analgesics (for example, ibuprofen, paracetamol or codeine) — the choice depends on the severity of pain, personal preferences, tolerability, and risk of adverse effects.

- For prescribing information on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), paracetamol, and codeine, see the CKS topic on Analgesia - mild-to-moderate pain.

- Consider offering a topical NSAID.

- Encourage activity and a return to a normal lifestyle (including work) as soon as possible.

Chronic:

- Postural aspects in daily activities, work, and sport should be identified and corrected where possible.

- A reduction from several pillows at night to one pillow will help many people.

- Referral to a pain clinic for a multidisciplinary pain management programme is reasonable in people with neck pain for more than 12 weeks who fail to respond to management in primary care[23].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, Devaney LL, Clewley D, Walton DM, Sparks C, Robertson EK, Altman RD, Beattie P, Boeglin E. Neck pain: revision 2017: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2017 Jul;47(7):A1-83.

- ↑ Moffett J, McLean S. The role of physiotherapy in the management of non-specific back pain and neck pain. Rheumatology. 2006 Apr 1;45(4):371-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. Bmj. 2007 Mar 8;334(7592):527-31.

- ↑ The 7 Faces of Neck Pain. Havard Health. Available from:https://www.health.harvard.edu/pain/7-faces-of-neck-pain (accessed 27 August, 2021)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hoy DG, Protani M, De R, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of neck pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010 Dec;24(6):783-92.

- ↑ Elbinoune I, Amine B, Shyen S, Gueddari S, Abouqal R, Hajjaj-Hassouni N. Chronic neck pain and anxiety-depression: prevalence and associated risk factors. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016 Sep 9;24(1).

- ↑ Hush JM, Michaleff Z, Maher CG, Refshauge K. Individual, physical and psychological risk factors for neck pain in Australian office workers: a 1-year longitudinal study. European spine journal. 2009 Oct;18(10):1532-40.

- ↑ Abu-Naser SS, Almurshidi SH. A knowledge based system for neck pain diagnosis. Available from: http://dstore.alazhar.edu.ps/xmlui/handle/123456789/384. Accessed 30 August, 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Magee DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment 5th ed. St. Louis, Mo, Saunders Elsevier. 2008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Childress MA, Becker BA. Nonoperative management of cervical radiculopathy. American family physician. 2016 May 1;93(9):746-54.

- ↑ Cooper G. Types of Neck Pain. Spine-Health. Available from: https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/neck-pain/types-neck-pain (accessed 21 May, 2021)

- ↑ Ramanayake RP, Basnayake BM. Evaluation of red flags minimizes missing serious diseases in primary care. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2018 Mar;7(2):315.

- ↑ Rubinstein SM, Pool JJ, van Tulder MW, Riphagen II, de Vet HC. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests of the neck for diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007; 16: 307-319.

- ↑ Trippolini MA, Janssen S, Hilfiker R, Oesch P. Measurement properties of the modified spinal function sort (M-SFS): is it reliable and valid in workers with chronic musculoskeletal pain?. Journal of occupational rehabilitation. 2018 Jun;28(2):322-31.

- ↑ Kim R, Wiest C, Clark K, Cook C, Horn M. Identifying risk factors for first-episode neck pain: a systematic review. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2018 Feb 1;33:77-83.

- ↑ Cerezo-Téllez E, Torres-Lacomba M, Fuentes-Gallardo I, Perez-Muñoz M, Mayoral-del-Moral O, Lluch-Girbés E, Prieto-Valiente L, Falla D. Effectiveness of dry needling for chronic nonspecific neck pain: a randomized, single-blinded, clinical trial. Pain. 2016 Sep 1;157(9):1905-17.

- ↑ Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment. Laser Treatment of Neck Pain [Internet]. Stockholm: Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU); 2014 May 20. SBU Alert Report No. 2014-03.

- ↑ Zronek M, Sanker H, Newcomb J, Donaldson M. The influence of home exercise programs for patients with non-specific or specific neck pain: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2016 Mar 14;24(2):62-73.

- ↑ Paolucci T, Agostini F, Paoloni M, de Sire A, Verna S, Pesce M, Ribecco L, Mangone M, Bernetti A, Saggini R. Efficacy of TENS in Cervical Pain Syndromes: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Applied Sciences. 2021 Jan;11(8):3423.

- ↑ Kroeling P, Gross A, Graham N, Burnie SJ, Szeto G, Goldsmith CH, Haines T, Forget M. Electrotherapy for neck pain. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013(8).

- ↑ Paquin JP, Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Dumas JP. Effects of SNAG mobilization combined with a self-SNAG home-exercise for the treatment of cervicogenic headache: a pilot study. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2021 Feb 6:1-1.

- ↑ Borman P, Keskin D, Ekici B, Bodur H. The efficacy of intermittent cervical traction in patents with chronic neck pain. Clinical rheumatology. 2008 Oct 1;27(10):1249-53.

- ↑ Williams N, Hoving J. Neck pain. Jones R, Britten N, culpepper L et al.