Lumbar Differential Diagnosis

Top Contributors - Jess Bell, Carin Hunter, Jorge Rodríguez Palomino and Ewa Jaraczewska

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Non-specific low back pain accounts for over 90% of patients presenting to primary care with low back pain[1][2] - these make up the majority of individuals with low back pain who present for physiotherapy. A physiotherapy assessment aims to identify impairments that may have contributed to the onset of the pain, or which increase the likelihood of developing persistent pain. These include biological factors (eg. weakness, stiffness), psychological factors (eg. depression, fear of movement and catastrophisation) and social factors (eg. work environment). [3]

Non-specific low back pain is defined as low back pain not attributable to a recognizable, known specific pathology (eg, infection, tumour, osteoporosis, lumbar spine fracture, structural deformity, inflammatory disorder,radicular syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome). [4]

Non-specific low back pain is usually categorized in 3 subtypes: acute, sub-acute and chronic low back pain. This subdivision is based on the duration of the back pain. Acute low back pain is an episode of low back pain for less than 6 weeks, sub-acute low back pain between 6 and 12 weeks and chronic low back pain for 12 weeks or more.[5]

Once serious spinal pathology and specific causes of back pain have been ruled out the patient is classified as having non-specific low back pain. If no serious pathology is suspected there is no indication for x-rays or MRI diagnostic imaging unless guidance is need to change the management protocol.[6]

Diagnosis versus Classification[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis is typically looked at as a pathoanatomical model, whereas the goal of classification systems is to guide treatment. This ensures not all back pain is treated the same. If a patient does not have a clear diagnosis, they are referred to as having non-specific low back pain.

Two patients with the diagnosis of an L5/S1 disk herniation on MRI, but one improves with repeated extensions and is classified with having an extension directional preference, while the other does not.

Imaging[edit | edit source]

Please see more information in Practical Decision Making in Physiotherapy Practice but to summarise:

- Imaging is needed if red flags are present or if no improvement with conservative care within 6 weeks. If you’re unsure about a red flag you can often treat a little to see if they improve.

- Imaging is recommended if it will change the course of treatment

- A lot of imaging findings correlate with low back pain. This doesn’t mean we can’t help them, but most imaging findings that people have do have a correlation with low back pain. That doesn’t mean everyone with imaging findings has pain, but often the more findings there are the higher chance the person has pain. We can still help them though!

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

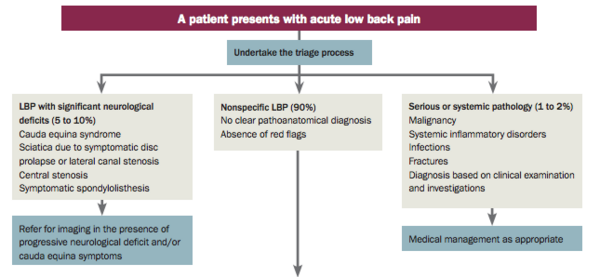

Initially, you should complete a good, comprehensive lumbar assessment. Once this is complete, you then triage the patient, as explained in the Lumbar Assessment page, by the image below:

For this, you'll need knowledge of Red Flags and conditions that can cause neurological deficits. For more information, please see the conditions below which are important to know about when considering a differential diagnosis. An unclear presentation is where we can be valuable with out assessment skills and clinical reasoning:

- Specific Low Back Pain

- Cauda Equina Syndrome

- Lumbar Radiculopathy

- Disc Herniation

- Spinal Stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Piriformis Syndrome

- Sacroiliac Joint Pain (not dysfunction)

- Osteoarthritis

- Sciatica

There are a few key generalisations to consider when looking at a differential diagnosis:[7]

- Neurological testing isn't an exact diagnosis but it gives a very good indication of where the problem lies, how to treat the patient and what to avoid to prevent injury or flare up.[7]

- If you are considering an extremity as the source of lower back pain or symptoms, the likelihood of it being the extremity is far less if the extremity has a full, pain free range of motion when tested.[7]

After our assessment, we should consider the asterisk signs that we have made note of throughout our examination and use these to help decide how to treat using a "signs and symptoms" treatment approach.

An asterisk sign is also known as a comparable sign. It is something that you can reproduce/retest that often reflects the primary complaint. It can be functional or movement specific. It is used to measure if symptoms are improving or worsening.

Is there a difference between flexion position to relieve pain and end range flexion?

For the spine, how do you balance the philosophies of extension to relieve symptoms and grading back into aggravating movements/positions to decrease pain and have full return of function? In here they related acute pathology like a “brain freeze”. How is back pain that doesn’t have either identifiable pathology on MRI or pathology that is likely causative on MRI?

Starting at 1 hr and 16 mins the discussion turns to non-specific low back pain.

What is the difference between reasoning and certainty?[edit | edit source]

How do you balance use of a pathoanatomical approach and signs and symptoms approach* with 1) Grade 2 ankle sprain 2) Partial thickness rotator cuff tear 3) R sided low back pain with imaging findings of R L4/L5 disc bulge and facet arthropathy

*Pathoanatomical approach means that you are treating to improve anatomy while a signs and symptoms approach means you test signs and ask for symptoms, treat, and then retest to assess for progress.

Differentiating between Hip and Lumbar Pain:

In this video you can see a live patient examination differentiating between hip and lumbar pain:

Notice that spine was greater than half of the time for hip, thigh/leg, and arm/forearm.

It’s also interesting to note that Table 1 reported that in the extremity group 10% had current spinal pain while 19% in the spinal group had current spinal pain. Thus, current spinal pain raises the pre-test probability of the extremity being from a spinal source from 10% to 19% overall. It’s unknown what the pre-test probability for current spinal pain for each of the body regions.

Article link (no need to explore the whole article for this module unless you choose to do so)

This article looks at likelihood to improve with MDT/repeated motion spine treatment. These are the odds ratios of indicators.

Data is taken from 319 participants who had extremity pain that neither they or a referring physician thought was from the spine.

To be classified as the spine or extremity group they had to have improvement in their asterisk sign by repeated motions. The article does mention future visits, but I don’t know how many visits the participants came to. My guess is that they didn’t participate in many, but were able to figure out their response in 2-3 visits.

Additional Reading[edit | edit source]

Rastogi, Ravi, et al. "Exploring indicators of extremity pain of spinal source as identified by Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT): a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study." Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy (2022): 1-8.

Rosedale, Richard, et al. "A study exploring the prevalence of Extremity Pain of Spinal Source (EXPOSS)." Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy 28.4 (2020): 222-230.

Physiopedia Pages:

- Low Back Pain

- Lumbar Assessment

- Low Back Pain Guidelines

- Differentiating Inflammatory and Mechanical Back Pain

- Non Specific Low Back Pain

- Specific Low Back Pain

Podcast Links:[edit | edit source]

- The Back Pain Podcast: Piriformis syndrome

- The Back Pain Podcast: Is my pain from my sacroiliac joint?

- Modern Pain Podcast: Lumbar Stenosis

- The Back Pain Podcast Episode 82: Flexion, Extension, Radicular Pain & Disc Pathology with Adam Meakins and Dr. Mark Laslett

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Traeger A, Buchbinder R, Harris I, Maher C. Diagnosis and management of low-back pain in primary care. CMAJ. 2017 Nov 13;189(45):E1386-E1395.

- ↑ Koes BW, Van Tulder M, Thomas S. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Bmj. 2006 Jun 15;332(7555):1430-4.

- ↑ M.Hancock. Approach to low back pain. RACGP, 2014, 43(3):117-118

- ↑ Balagué, Federico, et al. "Non-specific low back pain." The Lancet 379.9814 (2012): 482-491. Level of evidence 1A

- ↑ Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ, Hollis S. Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subchronic low back trouble. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Mar 15;20(6):722-8.Level of evidence 3C

- ↑ Almeida M, Saragiotto B, Richards B, Maher C. Primary care management of non-specific low back pain: key messages from recent clinical guidelines. Med J Aust 2018; 208 (6): 272-275

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Rainey N. Differential Diagnosis Course. Physiopedia Plus. 2023.