Lumbar Differential Diagnosis: Difference between revisions

Carin Hunter (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Carin Hunter (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

* If you are considering an extremity as the source of lower back pain or symptoms, the likelihood of it being the extremity is far less if the extremity has a full, pain free range of motion when tested.<ref name=":0" /> | * If you are considering an extremity as the source of lower back pain or symptoms, the likelihood of it being the extremity is far less if the extremity has a full, pain free range of motion when tested.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* In a study by Rastogi Ravi, et al<ref>Rastogi R, Rosedale R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10669817.2022.2030625?scroll=top&needAccess=true&role=tab Exploring indicators of extremity pain of spinal source as identified by Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT): a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study.] Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2022 May 4;30(3):172-9.</ref>, it shows that current spinal pain raises the the pre-test probability of the extremity being from a spinal source from 10% to 19% overall. | * In a study by Rastogi Ravi, et al<ref>Rastogi R, Rosedale R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10669817.2022.2030625?scroll=top&needAccess=true&role=tab Exploring indicators of extremity pain of spinal source as identified by Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT): a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study.] Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2022 May 4;30(3):172-9.</ref>, it shows that current spinal pain raises the the pre-test probability of the extremity being from a spinal source from 10% to 19% overall. | ||

* According to the table below, a high percentage of people reporting pain in their hip, thigh or leg have a spinal source of their pain. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+Contingency Table of the Proportions of Spinal or Extremity Source of Symptoms in Each Region<ref>Rosedale R, Rastogi R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10669817.2019.1661706 A study exploring the prevalence of Extremity Pain of Spinal Source (EXPOSS).] Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2020 Aug 7;28(4):222-30.</ref> | |||

!Regions | |||

!Extremity Source Frequency (%) | |||

!Spinal Source Frequency (%) | |||

!Total | |||

|- | |||

|Hip | |||

|9 (29.0%) | |||

|22 (71.0%) | |||

|31 | |||

|- | |||

|Thigh/Leg | |||

|5 (27.8%) | |||

|12 (72.2%) | |||

|18 | |||

|- | |||

|Knee | |||

|58 (74.4%) | |||

|20 (25.6%) | |||

|78 | |||

|- | |||

|Ankle/Foot | |||

|34 (70.8%) | |||

|14 (29.2%) | |||

|48 | |||

|- | |||

|Shoulder | |||

|44 (52.4%) | |||

|40 (47.6%) | |||

|84 | |||

|- | |||

|Arm/Forearm | |||

|2 (16.7%) | |||

|10 (83.3%) | |||

|12 | |||

|- | |||

|Elbow | |||

|14 (56.0%) | |||

|11 (44.0%) | |||

|25 | |||

|- | |||

|Wrist/Hand | |||

|16 (61.5%) | |||

|10 (38.5%) | |||

|26 | |||

|- | |||

|Total | |||

|182 (56.5%) | |||

|140 (43.5%) | |||

|322 | |||

|} | |||

===== '''Pathoanatomical Approach Compared to a Signs and Symptoms Approach:''' ===== | ===== '''Pathoanatomical Approach Compared to a Signs and Symptoms Approach:''' ===== | ||

<blockquote>Pathoanatomical approach means that you are treating to improve anatomy while a signs and symptoms approach means you test signs and ask for symptoms, treat, and then retest to assess for progress.</blockquote>After our assessment, we should consider the asterisk signs that we have made note of throughout our examination and use these to help decide how to treat using a "signs and symptoms" treatment approach. | <blockquote>Pathoanatomical approach means that you are treating to improve anatomy while a signs and symptoms approach means you test signs and ask for symptoms, treat, and then retest to assess for progress.</blockquote>After our assessment, we should consider the asterisk signs that we have made note of throughout our examination and use these to help decide how to treat using a "signs and symptoms" treatment approach. | ||

Revision as of 16:10, 2 February 2023

Top Contributors - Jess Bell, Carin Hunter, Jorge Rodríguez Palomino and Ewa Jaraczewska

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Non-specific low back pain accounts for over 90% of patients presenting to primary care with low back pain. [1][2] This makes up the majority of individuals with low back pain who present for physiotherapy. A physiotherapy assessment aims to identify impairments that may have contributed to the onset of the pain, or which increase the likelihood of developing persistent pain. These include biological factors (eg. weakness, stiffness), psychological factors (eg. depression, fear of movement and catastrophisation) and social factors (eg. work environment). [3]

Non-specific low back pain is defined as low back pain not attributable to a recognizable, known specific pathology[4] (eg, infection, tumour, osteoporosis, lumbar spine fracture, structural deformity, inflammatory disorder,radicular syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome). [5]

Non-specific low back pain is usually categorized in 3 subtypes: acute, sub-acute and chronic low back pain[6]. This subdivision is based on the duration of the back pain. Acute low back pain is an episode of low back pain for less than 6 weeks, sub-acute low back pain between 6 and 12 weeks and chronic low back pain for 12 weeks or more.[7]

Once serious spinal pathology and specific causes of back pain have been ruled out the patient is classified as having non-specific low back pain. If no serious pathology is suspected there is no indication for x-rays or MRI diagnostic imaging unless guidance is need to change the management protocol.[8][9]

Diagnosis versus Classification[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis is typically looked at as a pathoanatomical model, whereas the goal of classification systems is to guide treatment. This ensures not all back pain is treated the same. If a patient does not have a clear diagnosis, they are referred to as having non-specific low back pain.

Two patients with the diagnosis of an L5/S1 disk herniation on MRI, but one improves with repeated extensions and is classified with having an extension directional preference, while the other does not.

Imaging[edit | edit source]

Please see more information in Practical Decision Making in Physiotherapy Practice but to summarise:

- Imaging is needed if red flags are present or if no improvement with conservative care within 6 weeks. If you’re unsure about a red flag you can often treat a little to see if they improve.

- Imaging is recommended if it will change the course of treatment[10]

- A lot of imaging findings correlate with low back pain. This doesn’t mean we can’t help them, but most imaging findings that people have do have a correlation with low back pain. That doesn’t mean everyone with imaging findings has pain, but often the more findings there are the higher chance the person has pain. We can still help them though!

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

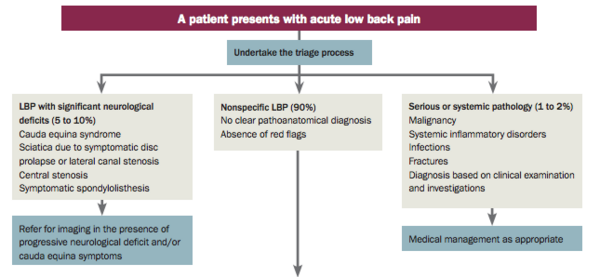

Initially, you should complete a good, comprehensive lumbar assessment. Once this is complete, you then triage the patient, as explained in the Lumbar Assessment page, by the image below:

For this, you'll need knowledge of Red Flags and conditions that can cause neurological deficits. For more information, please see the conditions below which are important to know about when considering a differential diagnosis. An unclear presentation is where we can be valuable with out assessment skills and clinical reasoning:

- Specific Low Back Pain

- Cauda Equina Syndrome

- Lumbar Radiculopathy

- Disc Herniation

- Spinal Stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Piriformis Syndrome

- Sacroiliac Joint Pain (not dysfunction)

- Osteoarthritis

- Sciatica

There are a few key generalisations to consider when looking at a differential diagnosis:[11]

- Neurological testing isn't an exact diagnosis but it gives a very good indication of where the problem lies, how to treat the patient and what to avoid to prevent injury or flare up.[11]

- If you are considering an extremity as the source of lower back pain or symptoms, the likelihood of it being the extremity is far less if the extremity has a full, pain free range of motion when tested.[11]

- In a study by Rastogi Ravi, et al[12], it shows that current spinal pain raises the the pre-test probability of the extremity being from a spinal source from 10% to 19% overall.

- According to the table below, a high percentage of people reporting pain in their hip, thigh or leg have a spinal source of their pain.

| Regions | Extremity Source Frequency (%) | Spinal Source Frequency (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hip | 9 (29.0%) | 22 (71.0%) | 31 |

| Thigh/Leg | 5 (27.8%) | 12 (72.2%) | 18 |

| Knee | 58 (74.4%) | 20 (25.6%) | 78 |

| Ankle/Foot | 34 (70.8%) | 14 (29.2%) | 48 |

| Shoulder | 44 (52.4%) | 40 (47.6%) | 84 |

| Arm/Forearm | 2 (16.7%) | 10 (83.3%) | 12 |

| Elbow | 14 (56.0%) | 11 (44.0%) | 25 |

| Wrist/Hand | 16 (61.5%) | 10 (38.5%) | 26 |

| Total | 182 (56.5%) | 140 (43.5%) | 322 |

Pathoanatomical Approach Compared to a Signs and Symptoms Approach:[edit | edit source]

Pathoanatomical approach means that you are treating to improve anatomy while a signs and symptoms approach means you test signs and ask for symptoms, treat, and then retest to assess for progress.

After our assessment, we should consider the asterisk signs that we have made note of throughout our examination and use these to help decide how to treat using a "signs and symptoms" treatment approach.

An asterisk sign is also known as a comparable sign. It is something that you can reproduce/retest that often reflects the primary complaint. It can be functional or movement specific. It is used to measure if symptoms are improving or worsening.

Differentiating between Hip and Lumbar Pain:[edit | edit source]

In this video you can see a live patient examination differentiating between hip and lumbar pain:

Additional Resources[edit | edit source]

Physiopedia Pages:[edit | edit source]

- Low Back Pain

- Lumbar Assessment

- Low Back Pain Guidelines

- Differentiating Inflammatory and Mechanical Back Pain

- Non Specific Low Back Pain

- Specific Low Back Pain

Podcast Links:[edit | edit source]

- The Back Pain Podcast: Piriformis syndrome

- The Back Pain Podcast: Is my pain from my sacroiliac joint?

- Modern Pain Podcast: Lumbar Stenosis

- The Back Pain Podcast Episode 82: Flexion, Extension, Radicular Pain & Disc Pathology with Adam Meakins and Dr. Mark Laslett

Journal Articles and Books:[edit | edit source]

- Casser HR, Seddigh S, Rauschmann M. Acute lumbar back pain: investigation, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2016 Apr;113(13):223.

- Casiano VE, Dydyk AM, Varacallo M. Back pain.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Traeger A, Buchbinder R, Harris I, Maher C. Diagnosis and management of low-back pain in primary care. CMAJ. 2017 Nov 13;189(45):E1386-E1395.

- ↑ Koes BW, Van Tulder M, Thomas S. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Bmj. 2006 Jun 15;332(7555):1430-4.

- ↑ M.Hancock. Approach to low back pain. RACGP, 2014, 43(3):117-118

- ↑ Otero-Ketterer E, Peñacoba-Puente C, Ferreira Pinheiro-Araujo C, Valera-Calero JA, Ortega-Santiago R. Biopsychosocial Factors for Chronicity in Individuals with Non-Specific Low Back Pain: An Umbrella Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Aug 16;19(16):10145.

- ↑ Balagué, Federico, et al. "Non-specific low back pain." The Lancet 379.9814 (2012): 482-491. Level of evidence 1A

- ↑ Hock M, Járomi M, Prémusz V, Szekeres ZJ, Ács P, Szilágyi B, Wang Z, Makai A. Disease-Specific Knowledge, Physical Activity, and Physical Functioning Examination among Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Sep 23;19(19):12024.

- ↑ Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ, Hollis S. Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subchronic low back trouble. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Mar 15;20(6):722-8.Level of evidence 3C

- ↑ Hall AM, Aubrey-Bassler K, Thorne B, Maher CG. Do not routinely offer imaging for uncomplicated low back pain. bmj. 2021 Feb 12;372.

- ↑ Almeida M, Saragiotto B, Richards B, Maher C. Primary care management of non-specific low back pain: key messages from recent clinical guidelines. Med J Aust 2018; 208 (6): 272-275

- ↑ Al-Hihi E, Gibson C, Lee J, Mount RR, Irani N, McGowan C. Improving appropriate imaging for non-specific low back pain. BMJ Open Quality. 2022 Feb 1;11(1):e001539.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Rainey N. Differential Diagnosis Course. Physiopedia Plus. 2023.

- ↑ Rastogi R, Rosedale R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. Exploring indicators of extremity pain of spinal source as identified by Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT): a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2022 May 4;30(3):172-9.

- ↑ Rosedale R, Rastogi R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. A study exploring the prevalence of Extremity Pain of Spinal Source (EXPOSS). Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2020 Aug 7;28(4):222-30.