Hodgkin's Lymphoma

Original Editors - Ann Bedwell from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Ann Bedwell, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Elaine Lonnemann, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Kapil Narale, Aya Alhindi, 127.0.0.1, Tony Lowe, Wendy Walker, Evan Thomas, Venugopal Pawar, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane and Aminat Abolade

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Hodgkin lymphoma or Hodgkin disease (HD) is a type of lymphoma and accounts for ~1% of all cancers.

- Hodgkin disease spreads contiguously and predictably along lymphatic pathways and is curable in ~90% of cases, depending on its stage and sub-type[1].

This type of cancer is malignant and may travel to other parts of the body. As it progresses, it may compromise the body’s ability to fight infection since it is attacking the immune system.[2]

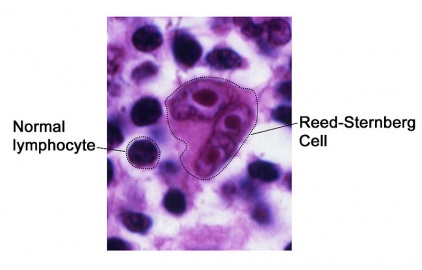

The disease is characterised by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells (considered to be a type of B cell). These cells however only occupy a very small proportion (<5%) of the overall cell population of the affected lymph node. Contiguous spread is another feature. EBV infection is present in 40-80% depending on subtype[1]

- The Reed-Sternberg cell is “part of the tissue macrophage system and have twin nuclei and nucleoli that give them the appearance of owl eyes.”[3]

Subtypes

There are five recognised histological subtypes, subdivided into two groups, classical and non-classical.

- Classical

Positive for CD15/CD30 and negative for CD20/CD45/EMA:

- nodular sclerosing: ≈70%

- mixed cellularity: ≈25%

- lymphocyte-rich: 5%

- lymphocyte depleted: <5%

2, Non-classical

Positive for CD 19, 20, 22, 79a/EMA and negative for CD15/CD30:

- nodular lymphocyte predominant (nodular paragranuloma)[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

It is estimated that HL accounts for approximately 10% of cases of newly diagnosed lymphoma in the United States (8260 of 80,500 cases), and the remainder are non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

- Of 21,210 estimated deaths yearly because of lymphoma, about 1070 (or 5%) are from HL (accounting for about 0.5% of newly diagnosed cases of cancer in the United States and about 0.2% of all cancer deaths).

- Males are expected to comprise about 56% of patients newly diagnosed with HL in 2017

- The median age of diagnosis is 39 years; HL is most frequently seen in the group ages 20 to 34 years, which makes up almost one‐third of new diagnoses.

The incidence rates

- do not seem to vary between white and black Americans (3.1 new cases per 100,000 males)

- are about one‐half as much in Asians/Pacific Islanders (1.6 new cases per 100,000 males) and American Indians/Alaskan Natives.

- are lower in Hispanic Americans (2.6 new cases per 100,000 males) compared with white and black populations.

- of HL have stayed flat since the mid‐1970s, but mortality rates have steadily declined from 1.3 cases per 100,000 in 1975 to 0.3 cases per 100,000 in 2014.

Across all stages of diagnosis, the relative 5‐year survival of patients with HL has improved from 70% to 85% during the same period[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs

- Painless, unilateral, enlargement of nymph node usually in the neck, underarm or groin[6]

- The lymph nodes should be examined based on the size, mobility, consistency and tenderness. A lymph node that is “over 1 centimeter in diameter and firm or rubbery consistency or tender are considered suspicious

- Lymph nodes that are soft and tender to touch are usually indicative of infection.

- Any changes in the shape, size, consistency, or mobility are red flags and should be reported to a physician immediately.

Symptoms

- Fatigue[6]

- Fever and chills that come and go

- Typically peaks in the late afternoon

- Itching all over the body that cannot be explained

- Itching occurs mostly at night

- Loss of appetite

- Soaking night sweats

- Painless swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin (swollen glands)

- Weight loss that cannot be explained

Other symptoms that may occur with this disease:

- Coughing, chest pains, or breathing problems if there are swollen lymph nodes in the chest[7]

- Excessive sweating[7]

- Pain or feeling of fullness below the ribs due to swollen spleen or liver[7]

- Pain in lymph nodes after drinking alcohol[7]

- Skin blushing or flushing[7]

- Malaise[6]

- Anorexia[6]

- Symptoms may occur due to the obstruction or compression of structures by the enlarged lymph nodes. This may cause edema in the neck, face or right arm due to blockage of the superior vena cava or renal failure from blockage of the urethra.[6]

- Obstruction of bile ducts results in liver damage or jaundice, which will present as a yellowish color to the skin

- “Mediastinal lymph node enlargement with involvement of lung parenchyma and invasion of the pulmonary pleura progressing to the parietal pleura may result in pulmonary symptoms, including nonproductive cough, dyspnea, chest pain and cyanosis.”[6]

- Nerve root pain and paraplegia could occur if the cancer spreads to the bones

- Invasion pericardium caused by enlarged “penetrating lymph nodes adjacent to the heart”[3]

- Hepatoslenomegaly[3]

Many of these signs and symptoms may be due to other health problems.

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

No associated co-morbidities were found although there are risks associated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy described further in the Medications section.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are the main treatments for HL.

- Depending on the case, one or both of these treatments might be used.

- Certain patients might be treated with immunotherapy or with a stem cell transplant, especially if other treatments haven’t worked. Except for biopsy and staging, surgery is rarely used to treat HL.[8]

Even in advanced‐stage disease, HL is highly curable with combination chemotherapy, radiation, or combined‐modality treatment.

- Although the same doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine chemotherapeutic regimen has been the mainstay of therapy over the last 30 years, risk‐adapted approaches have helped de‐escalate therapy in low‐risk patients while intensifying treatment for higher risk patients.

- Even patients who are not cured with initial therapy can often be salvaged with alternate chemotherapy combinations, the novel antibody‐drug conjugate brentuximab, or high‐dose autologous or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

- The programmed death‐1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab have both demonstrated high response rates and durable remissions in patients with relapsed/refractory HL.

- Alternate donor sources and reduced‐intensity conditioning have made allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation a viable option for more patients.

- Future research will look to integrate novel strategies into earlier lines of therapy to improve the HL cure rate and minimize long‐term treatment toxicities[5]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Hodgkin’s lymphoma presents like many other disorders, so it is hard to differentiate and diagnose. The following tests and procedures are taken to positively diagnose Hodgkin’s lymphoma:

- “Physical exam: Your doctor checks for swollen lymph nodes in your neck, underarms, and groin. Your doctor also checks for a swollen spleen or liver.”[9]

- Biopsy of lymph tissue that looks be involved and bone marrow. Once the sample is taken, it is checked for Reed-Sternberg cells that indicate Hodgkin’s lymphoma.[2]

- Blood Chemistry Tests: check protein levels, liver function tests, kidney function tests and uric acid levels[7]

- CT Scans: chest, abdomen and pelvis[7]

- X-Rays: show swollen lymph nodes[2]

- PET Scan: glucose is injected in the patient’s veins and be will more concentrated around cancerous cells[2]

- MRI[2]

Once tests reveal that a patient has Hodgkin’s lymphoma, additional tests will be done to see if the cancer has spread therefore finding out what stage the cancer is in.[7] Once the cancer stage has been found, future treatments can be planned and initiated.

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

The exact cause of Hodgkin’s lymphoma is unknown.[7][2] HL begins with an abnormal B cell, which is a type of lymph cell that is important in the body’s response to foreign intruders. When these B cells become abnormal they are called Reed-Sternberg cells. This cell continues to divide and make copies, but unlike normal cells, it does not die.[3] “The genes have the ability to mimic transmembrane receptors and activate the transcription factor NF-кB. NF-кB, through its function of regulating dozens of genes within the cell, plays a key role in the proliferation and survival of the malignant clones.”[3] Products of these genes include cytokines and chemokines. Most cytokines, mostly interleukins produce an environment where the Reed-Sternberg cells can flourish. These interleukins may attract inflammatory cells to survive as it is shown in the lab that they cannot survive without the inflammatory cells. Other interleukins restrain the activation of T cells that are normally used to destroy any unusual cell, while others “act as growth factors, encouraging proliferation, metastasis and angiogensis.”[3] The abnormal B cell is unable to die due to a protein called c-FLIP that usually signals cell death but is not able to function in the circumstances. Therefore the abnormal B cell is undying.[3]

The cells build up while attracting normal immune cells to cause tissue growth in the lymph nodes.[2][9]This mass of tissue growth is called the tumor. The reason that these B cells are malignant is unknown, but recent evidence implies that it begins from an infection or inflammation. Genes from a virus called Epstein-Barr have been found in half of all HL cases.[9]

Once the lymphoma begins in the lymph nodes, typically the neck, axilla or groin, it can travel to all other lymph nodes in the body then spread outside of the lymph nodes into any part of the body.[2][11]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

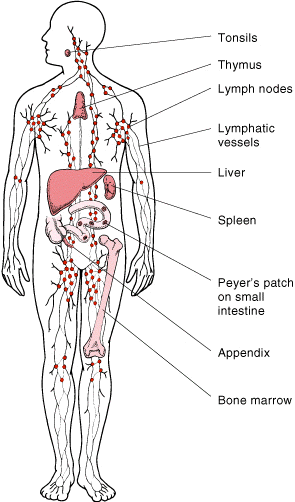

Hodgkin’s lymphoma primarily affects the lymph nodes in the neck, axillas, and groin but can also affect and grow to the spleen, liver, tonsils, thymus and bone marrow, which are all part of the lymphatic system. The spleen, composed of blood and lymphoid tissue, is where the final destruction of red blood cells, filtration and storage of blood takes place as well as production of lymphocytes. The liver is a vascular, glandular organ that secretes bile to aid in digestion and changes substances in blood that passes through it. The tonsils are masses of lymphoid tissue near on either side of the throat. The thymus gland is composed of lymph tissue and functions in cell-mediated immunity by developing T cells. This gland is highly active in the younger population, then disappears with age. Bone marrow is the inner part of the bone where blood cells are made. B cells, which are white blood cells that help to aid in fighting infection. These B cells are the particular cells in Hodgkin’s lymphoma that become abnormal and begin the multiply to form a tumor.[12]

Other organs and systems can be involved by way of metastasis. Hodgkin’s lymphoma can metastasize to all tissues of the body due to the lymphoreticular cells inhabiting all types of tissue except the central nervous system. “Hematological spread may also occur, possibly by means of direct infiltration of blood vessels.”[3]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Management of Hodgkin’s lymphoma is done by chemotherapy or a combination of chemotherapy and radiation. The different medications used in chemotherapy are listed above under the Medications section. However, treatment does depend on several different factors:

- The type of Hodgkin's lymphoma (most people have classic Hodgkin's)[7]

- The stage at which the cancer is at as well as number of lymph nodes involved[2]

- “A staging evaluation is necessary to determine the treatment plan”[7]

- Stage I: one lymph node region involved

- Stage II: two lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm involved

- Stage III: lymph node regions are involved on both sides of the diaphragm

- Stage IV: cancer is found outside the lymph nodes (i.e. bone)[7]

- “A staging evaluation is necessary to determine the treatment plan”[7]

- The size of the tumor:

- The patient's co-morbidities

- “Other factors, including weight loss, night sweats, and fever”[7]

- Age of patient[9]

- Whether the patient is pregnant or not[2]

Treatment is different for patients in a certain stage and age[7]:

- Stages I and II: treated with local radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both.

- Stage III: “treated with chemotherapy alone or a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy.”

- Stage IV: usually treated with chemotherapy alone

Surgery[edit | edit source]

There are several different types of surgery that may be performed to decrease or rid of any tumor. These are:

- Partial resection or debulking: used when only part of the tumor can be removed.

- Complete resection: the whole tumor is removed.

- Mohs surgery: each layer of the tumor is removed until it is completely gone

- Lymph node dissection

- Implantation of radioactive beads (brachytherapy)[13]

Chemotherapy[edit | edit source]

Chemotherapy is a mix of specific drugs that are introduced through the bloodstream to kill tumor cells. Most of the drugs are given intravenously, but some can also be given orally. Chemotherapy is given in cycles with a rest period. The amount of time spent in each cycle is determined by the type of drug used and stage of cancer.[14]

Radiation Therapy[edit | edit source]

Radiation therapy uses high energy x-rays to kill cancer cells and decrease pain. The duration of radiation therapy depends on what stage the cancer is in. Radiation is confined to a certain area, killing the cells in only that area. It is usually combined with chemotherapy and rarely used by itself.[9] Most children who receive radiation are given a low-dose.[2]

Side Effects of Radiation Therapy[edit | edit source]

- Increased risk of heart disease[2]

- Stroke[2]

- Thyroid problems[2]

- Infertility[2]

- Other forms of cancer[2]

- Red, dry tender skin[9]

- Fatigue[9]

Biotherapy[edit | edit source]

Biotherapy or tumor immunotherapy uses a pharmacological approach to genetically engineer antibodies that specifically attack antigens on cancer cells.[13]

Bone Marrow or Stem Cell Transplantation[edit | edit source]

Bone marrow or stem cell transplantation may be used if the cancer returns or if the patient is not responding to treatment. Bone marrow or stem cells are taken from the patient, frozen and stored. The patient then receives high dose chemotherapy to destroy all the cancerous cells. Then the frozen marrow or stem cells are injected into the body through the patient’s veins.[2]

Other Treatments[edit | edit source]

Additional treatments may be used due to symptoms:

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma focuses on cardiovascular and pulmonary health, strength, and flexibility in order to improve quality of life and reduce symptoms produced from cancer and treatments. Most physical therapy sessions focus on activities of daily living, but also focus on the ability to reduce fatigue. The ability to improve cardiovascular and pulmonary health along with strength and flexibility will allow patients the ability to help their tolerance to chemotherapy and radiation while maintaining or improving their ability to do everyday activities.[16] In a literature review by Courneya and Friedenreich, 24 empirical studies that were published between 1980 and 1997 showed that physical exercises and activity has a positive effect on quality of life in patients with cancer. Physical activity is able to increase functional health as well as psychological and emotional welfare.[17]

Research suggests that treadmill exercises (aerobic exercises) provide cardioprotective effects on the Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity[18].

Articles presented in the Literature Review by Courneya and Friedenreich

| Title, Author and Year |

Study Design |

Summary and Results |

| Nelson JP. Perceived health, self-esteem, health habits, and perceived benefits and barriers to exercise in women who have and who have not experienced stage I breast cancer. 1991. |

Cross-sectional |

Patients self reported exercises they did posttreatment. Healthy behaviors showed a positive relationship with self-esteem. |

| Young-McCaughan S, Sexton DL. A retrospective investigation of the relationship between aerobic exercise and quality of life in women with breast cancer. 1991. |

Retrospective |

Patients self reported exercise during or after treatment. Patients who exercised reported a higher QOL. |

| Baldwin MK, Courneya KS. Exercise and self-esteem in breast cancer survivors: An application of the exercise and self-esteem model. 1997. |

Cross-Sectional |

Patients self reported mild, moderate or strenuous exercise during or after treatment. Strenuous physical activity related positively with self-esteem and physical competence. |

| Bremer BA, Moore CT, Bourbon BM, Hess DR, Bremer KL. Perceptions of control, physical exercise, and psychological adjustment to breast cancer in South African women. 1997. |

Cross-sectional |

Patient’s self reported posttreatment exercises. No difference was found between patients that exercised and those that did not. |

| Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Relationship between exercise pattern across the cancer experience and current quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. 1997. |

Retrospective |

Patients self reported mild, moderate and strenuous exercise prediagnosis, during treatment and after treatment. “Survivors who permanently relapsed from pretreatment to posttreatment reported lowest QOL.” |

| Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Relationship between exercise during cancer treatment and current quality of life in survivors of breast cancer. 1997. |

Retrospective |

Self reported mild, moderate and strenuous exerciseprediagnosis, during treatment and after treatment. Patients who maintained an exercise program from pre- to post-treatment reported the highest QOL. |

| BuettnerLL. Personality changes and physiological changes of a personalized fitness enrichment program for cancer patients. 1980. |

Quasi-experimental |

Exercise sessions with cardiovascular, strength and flexibility during post-treatment. Experimental group showed an increase in strength, functional capacity and personality. |

| Winningham ML. Effects of a bicycle ergometry program on functional capacity and feelings of control in women with breast cancer. 1983. |

Quasi-experimental |

Patients exercised on a cycle ergometer during chemotherapy. Experimental group increased their functional capacity. |

| Cunningham BA, Morris G, Cheney CL et al. Effects of resistance exercise on skeletal muscle in marrow transplant recipients receiving total parenteral nutrition. 1986. |

Experimental |

Exercise following bone marrow transplant. Experimental group maintained creatine exertion level. |

| MacVicar MG, Winningham ML. Promoting the functional capacity of cancer patients. 1986. |

Quasi-experimental |

Exercise on cycle ergometer during chemotherapy. Experimental group increased functional capacity, where controls decreased. |

| Winnginham ML, MacVicar MG. The effect of aerobic exercise on patient reports of nausea. 1988. |

Experimental |

Exercise on a cycle ergometer during chemotherapy. Experimental group had a larger decrease in nausea. |

| Decker WA, Turner-McGlade K, Fehir KM. Psychosocial aspects and the physiological effects of a cardiopulmonary exercise program in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation for acute leukemia. 1989. |

Quasi-experimental |

Home-based exercise program before and after bone marrow transplant. Patients exhibited a decreased aerobic capacity and weight loss. |

| MacVicar MG, Winningham ML, Neckel JL. Effects of aerobic interval training on cancer patients’ functional capacity. 1989. |

Experimental |

Exercise on a cycle ergometer during chemotherapy. Experimental group increased their functional capacity. |

| Winningham ML, MacVicar MG, Bondoc M, Anderson JL, Minton JP. Effect of aerobic exercise on body weight and composition in patients with breast cancer on adjuvant chemotherapy. 1989. |

Experimental |

Exercise on a cycle ergometer during chemotherapy. Experimental group decreased their percent body fat and increased their lean body mass. |

| Pfalzer LA. The responses of bone marrow transplant patients to graded exercise testing prior to transplant and after transplant with and without exercise training. 1990. |

Quasi-experimental |

Patient’s exercised on cycle ergometer after bone marrow transplant. Patient’s showed an increase in VO2, decreased depression and fatigue. |

| Peters C. Ausdauersport als rehabilitationsmassnahme in der krebs-nachsorge. 1992. |

Quasi-experimental |

Patient’s exercised on a cycle ergometer. Patient’s showed an increase in natural killer cell activity. |

| Seifert E, Ewert S, Werle J. Exercise and sports therapy for patients with head and neck tumors. 1992. |

Quasi-experimental |

Group exercise showed favor in the experimental group but there wasn’t a significant difference with the control group. |

| Sharkey AM, Carey AB, Heise CT, Barber G. Cardiac rehabilitation after cancer therapy in children and adults. 1993. |

Quasi-experimental |

Exercises showed an increase in peak oxygen uptake and ventilator anaerobic threshold. |

| Mock V, Burke MB, Sheehan P, et al. A nursing rehabilitation program for women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. 1994. |

Experimental |

Walking program showed an increase in physical functioning and fewer symptoms than the control group. |

| Nieman DC, Cook VD, Henson DA, et al. Moderate exercise training and natural killer cell cytotoxic activity in breast cancer patients. 1995. |

Experimental |

Walking and weight training program during post-treatment showed an increase in the 6 minute walk test and a decrease in heart rate. |

| Dimeo F, Bertz H, Finke J, et al. An aerobic exercise program for patients with haemotological malignancies after bone marrow transplantation. 1996. |

Quasi-experimental |

Treadmill walking post-bone marrow transplant showed an increase in physical performance. |

| Dimeo F, Tilmann MHM, Bertz H, et al. Aerobic exercise in the rehabilitation of cancer patients after high dose chemotherapy and autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation. 1997. |

Quasi-experimental |

Treadmill walking showed an increase in maximum performance and hemoglobin levels while decreasing fatigue. |

| Dimeo F, Fetscher S, Lange W, Mertelsmann R, Keul J. Effects of aerobic exercise on the physical performance and incidence of treatment-related complications after high-dose chemotherapy. 1997. |

Experimental |

Biking by use of a bed ergometer showed an increase in functional capacity and a decrease in pain and length of hospital stay. |

| Mock V, Dow KH, Meares CJ, et al. Effects of exercise on fatigue, physical functioning and emotional distress during radiation therapy for breast cancer. 1997. |

Experimental |

Home walking program during radiation increased patient’s functional capacity and decreased fatigue. |

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnoses include[19][20]:

- Actue lymphoblastic leukemia

- Lymphadenopathy

- Brucellosis

- Lymphoproliferative disorders

- Catscratch disease

- Mononucleosis and Epstein-Barr virus infection

- Cytomegalovirus infection

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Histoplasmosis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Lymph node disorder

- Tuberculosis

- Lymphadenitis

- Fibrosing mediastinitis

- Atypical mycobasteria

- AIDS

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- Systemic lupus erythmatosus

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

- Hodgkin's Lymphoma Case Study

- Hodgkin's lymphoma masquerading as vertebral osteomyelitis in a man with diabetes: a case report

- Hodgkin's lymphoma presenting with heart failure: a case report

- A case of nodular sclerosis Hodgkin’s lymphoma repeatedly relapsing in the context of composite plasma cell-hyaline vascular Castleman’s disease: successful response to rituximab and radiotherapy

Resources[edit | edit source]

- What you need to know aboutTM Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Lymphoma Research Foundation: resources for facts, information and support groups

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Radiopedia Hodgkin Disease Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/hodgkin-lymphoma

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Mayo Clinic Staff. Hodkgin’s lymphoma (Hodgkin’s Disease). http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/hodgkins-disease/DS00186. Updated November 5, 2010. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2009.

- ↑ UCTV. Conversations with History: The Story of Hodgkin’s Disease. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jBzMp-pnfcA. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Shanbhag S, Ambinder RF. Hodgkin lymphoma: a review and update on recent progress. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018 Mar;68(2):116-32. Available from:https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21438

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Goodman CC and Snyder TK. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. 4th edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2007.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 Zieve D, Chen Y. Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000580.htm. Updated March 3, 2010. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ ACS Hodgkins Disease Available from:https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/treating.html (last accessed 1.8.2020)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 National Cancer Institute. Hodgkin lymphoma. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/hodgkin. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ Head and Neck lymph nodes exam. http://doctorsgate.blogspot.com/2010/05/head-and-neck-lymph-nodes-exam.html Accessed on March 24, 2011.

- ↑ Lymph system. http://search.creativecommons.org/?q=lymph%20system. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ National Institutes of Health. Medical Dictionary. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/mplusdictionary.html. Updated July 11, 2010. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Billek-Sawhney B, Wells CL. Oncology considerations for the patient in acute care. Acute Care Perspectives. 2009; 18: (4): 3-24.

- ↑ Altekruse et al. SEER Stat Fact Sheet: Hodgkins lymphoma. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/hodg.html. Updated 2009. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ Biomedical Communications. http://www.biocom.arizona.edu/showproject.cfm?project=52. Accessed on March 24, 2011.

- ↑ Cancer Treatment Centers of America. Hodgkins Disease Treatments - Complementary and Alternative Medicines. http://www.cancercenter.com/hodgkins-disease/complementary-alternative-hodgkins-disease-treatment.cfm. Updated October 3, 2007. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Physical exercise and quality of life following cancer diagnosis: a literature review. Ann Behav Med. 1999; 21: (2): 171-179.

- ↑ Yang HL, Hsieh PL, Hung CH, Cheng HC, Chou WC, Chu PM, Chang YC, Tsai KL. Early Moderate Intensity Aerobic Exercise Intervention Prevents Doxorubicin-Caused Cardiac Dysfunction Through Inhibition of Cardiac Fibrosis and Inflammation. Cancers. 2020 May;12(5):1102.

- ↑ Alarcon PA. Pediatric Hodgkin Disease: Differential Diagnoses & Workup. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/987101-diagnosis. Updated December 2, 2008. Accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ MDGuidelines. Hodgkin’s Disease. http://www.mdguidelines.com/hodgkins-disease/differential-diagnosis. Accessed on February 27, 2011.