Facial Nerve

Original Editor - Wendy Walker.

Top Contributors - Wendy Walker, Kim Jackson, Scott Buxton, Lucinda hampton, Rishika Babburu, Evan Thomas, Samson Chengetanai, Tarina van der Stockt, Priyanka Chugh, WikiSysop, Jess Bell, Merinda Rodseth and Admin

One Page Owner - Wendy Walker as part of the One Page Project

Introduction[edit | edit source]

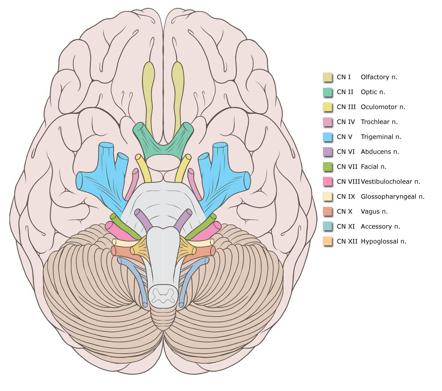

The Facial Nerve is the seventh Cranial Nerve.

It is composed of approximately 10,000 neurons, 7,000 of which are myelinated and innervate the muscles of facial expression.

The remaining 3,000 fibres are somatosensory and secretomotor, and are known as the Nervus Intermedius.

This nerve has an extremely complicated course, and the description below is a simplified overview which provides the main details which physiotherapists are required to be aware of when treating patients with damage to the Facial Nerve.

For a full description of the complexities of this nerve, please see the video lower down on the page.

Movements Produced[edit | edit source]

All movements of facial expression, including:

Smile, close eyes, pucker lips, wrinkle nose, raise eyebrows, frown.

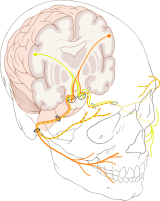

General Course of Nerve[edit | edit source]

In anatomical terms the facial nerve can be divided into 2 main parts [1]:

- Intracranial - inside the brain and the skull

- Extracranial - in the face and neck

Intracranial segment[edit | edit source]

The nerve arises in the pons, (lateral to the abducens nerve and medial medial to the vesibulococholear nerve) and it begins as 2 roots: a large motor root and a smaller sensory root, which is known as the Nervus Intermedius.

The facial nerve and the nervus intermedius pass through the cerebellopontine angle, and then through the internal acoustic meatus which is in the Temporal Bone.

Still within the Temporal Bone, the facial and nervus intermedius both enter the Fallopian Canal [AKA Facial Canal].

In the Fallopian/Facial Canal, the 2 roots (Facial and Nervus Intermedius) fuse together to form the Facial Nerve; the Facial Nerve forms the Geniculate Ganglion, and 3 small nerve branches originate:

- Greater Petrosal Nerve - this provides parasympathetic fibres to lacrimal glands of the eye and mucus membrane of the nasal cavity and palate

- Chorda Tympani - special sensory fibres which supply taste sensation for the anterior 2/3 of the tongue; also provides sympathetic fibres to the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands

- Nerve branch to the Stapedius muscle in the middle ear

The Facial Nerve then exits the Fallopian/Facial canal, leaving the cranium via the Stylomastoid Foramen of the Temporal Bone.

Extracranial segment[edit | edit source]

The first extracranial branch is Posterior Auricular Nerve which is the motor supply to some of the muscles around the ear, then immediately after this another small branch provides motor fibres to the posterior belly of the Digastric Muscle and to the Stylohyoid muscle.

It then passes between the stylohyoid and digastric muscle and enters the parotid gland, where it lies between the deep and superficial lobes of the gland. Here it divides into two main branches (at the pes asnerinus): superior temporofacial and inferior cervicofacial branches.

From the anterior border of the parotid gland, 5 branches emerge:

- temporal

- zygomatic

- buccal

- mandibular

- cervical

These branches have many and varied connections/pathways running between them; in addition, there are communicating pathways from other cranial nerves including (but not limited to) the Trigeminal Nerve, Vestibular/Auditory Nerve and Hypoglossal Nerve[2][1].

There is another detailed diagram of the course of the Facial Nerve on the Facial Palsy page.

The details of the exact connections between the five terminal branches can vary hugely in different individuals[3]. This should be no surprise to us, as it is easy to see the wide variety of different smile shapes, for instance. One recent study on cadavers, in 2018, looked at the length, diameter of divisions, number and course of terminal branches and the connections between them, and identified 12 different patterns[4].

Five Distal Branches[edit | edit source]

- Temporal (Frontal)

- Zygomatic

- Buccal

- Marginal mandibular

- Cervical

For details of the muscles listed below, please see the anatomy pages Facial Muscles - Upper Group and Facial Muscles - Lower Group.

The temporal or frontal trunk innervates the following muscles:

- Frontalis

- Orbicularis oculi (superior portion and palpebral region/eyelid)

- Corrugator supercilii

- Procerus (AKA Pyramidalis Nasi)

The zygomatic division innervates the following muscles:

- Orbicularis oculi (lower/inferior portion)

- Zygomaticus major (also supplied by buccal branch)

- Elevator ala nasi

- Levator labii superioris

The buccal division gives off fibres to innervate:

- Buccinator

- Orbicularis oris, superior portion

- Zygomaticus major (also supplied by zygomatic branch)

- Zygomaticus minor

- Risorius

- Levator Anguli Oris

- Compressor (AKA Transverse) nasi

- Dilatator naris muscles

- Depressor septi nasi (AKA Depressor Alae Nasi)

Mandibular division innervations are found in the following muscles:

- Quadratus labii inferioris

- Triangularis

- Mentalis

- Lower parts of the orbicularis oris

The cervical division provides platysma innervation.

Here is a video describing the course of the Facial Nerve, both intracranial and on the face:

Embryology[edit | edit source]

The facial nerve (along with the acoustic nerve, CN 8) arises from the fascioacoustic primordium which forms by the 3rd week of gestation.

The geniculate ganglion, greater superficial petrosal nerve and nervus intermedius are all visible by the 5th week of gestation.

The 2nd branchial arch gives rise to the muscles of facial expression in the 7th & 8th weeks. By the 11th week the facial nerve has developed its branches.

In the newborn baby the facial nerve anatomy is the same as that of an adult, with the exception of its location in the mastoid, which is more superficial in the baby.

Imaging[edit | edit source]

Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful in the diagnosis of injury to intratemporal and/or intracranial affections of the facial nerve[5], as they may reveal temporal fracture patterns (vertical, transversal, mixed) and oedema formation. Under certain circumstances, the facial nerve can be viewed, and swelling or disruption may be seen[6].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 May M, Schaitkin B. May M, Schaitkin B, eds. The Facial Nerve, 2nd Edition. New York, NY: Thieme; 2000.

- ↑ Bischoff EPE. Microscopic analysis of the anastomosis between the cranial nerves. In: Sacks EJ, Valtin EW, eds. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England; 1977

- ↑ Ashraf Raslan MD, Gerd Fabian Volk MD, Martin Möller, Vincent Stark, Nikolas Eckhardt, Orlando Guntinas-Lichius MD, 2017. High variability of facial muscle innervation by facial nerve branches: A prospective electrostimulation study. The Laryngoscope, Volume127, Issue 6 June 2017, Pages 1288-1295.

- ↑ Pascual PM, Maranillo E, Vázquez T, Simon de Blas C, Lasso JM, Sañudo JR. Extracranial Course of the Facial Nerve Revisited. The Anatomical Record, Volume 302, Issue 4, pages 599-608.

- ↑ Zimmermann, J., Jesse, S., Kassubek, J. et al. Differential diagnosis of peripheral facial nerve palsy: a retrospective clinical, MRI and CSF-based study. J Neurol 266, 2488–2494 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09387-w

- ↑ Kumar A, Mafee MF, Mason T. Value of imaging in disorders of the facial nerve. Top Magn Reson Imaging. Feb 2000;11(1):38-51. [Medline].