Coccygodynia (Coccydynia, Coccalgia, Tailbone Pain)

Original Editor - Maxime Tuerlinckx as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project

Top Contributors - Victoria Geropoulos, Nicole Hills, Maxime Tuerlinckx, Evan Thomas, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Redisha Jakibanjar, Admin, Daphne Jackson, WikiSysop, Aminat Abolade, Rosie Swift, Pacifique Dusabeyezu and Laura Ritchie

Definition / Description[edit | edit source]

Coccygodynia, sometimes referred to as coccydynia, coccalgia, coccygeal neuralgia or tailbone pain, is the term used to describe the symptoms of pain that occur in the region of the coccyx.[1][2][3][4] The pain is most commonly triggered in a sitting position but may also occur when the individual changes from a sitting to standing position.[3] Most cases will resolve within a few weeks to months, however for some patients the pain can become chronic, having negative impacts on quality of life.[3][4] For these individuals, management can be difficult due to the complex nature of coccygeal pain.[4]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

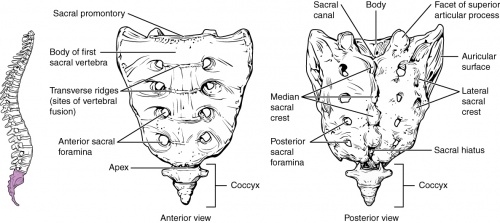

The coccyx is a triangular bone that forms the most distal segment of the spine.[1][3] It is composed of 3 to 5 coccygeal segments.[2] These segments fuse together to form a single bone with the exception of the first coccygeal segment, which might not fuse together with the second coccygeal segment.[2][3]The ventral aspect of the coccyx is concave in shape, while the dorsal aspect of the coccyx is convex in shape.[1]The first coccygeal segment is composed of articular processes that form the coccygeal cornua.[1][2][4] The coccygeal cornua articulates with the sacral cornua of the inferior sacral apex of S5.[1][2][4] This articulation creates a symphysis or synovial joint, which forms one of the borders of the foramen for the dorsal branch of the fifth sacral nerve route (S5).[1][4]

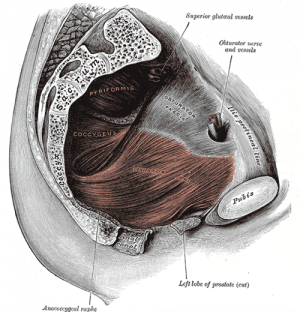

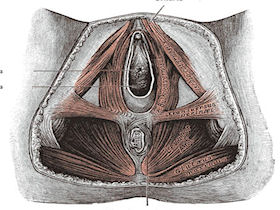

The coccyx serves as an attachment site for several muscles and ligaments.[4] Anteriorly, the coccyx is bordered by the levator ani muscle and the sacro-coccygeal ligament.[4] In an anterior (front) to posterior (back) direction, the lateral border of the coccyx serves as an insertion point for the coccygeal muscles, the sacrospinous ligament, the sacrotuberous ligament and the gluteus maximus.[4] Inferiorly, the tendon of the iliococcygeus muscle inserts onto the tip of the coccyx.[4]Together, these ligaments and muscles contribute to voluntary bowel control, as well, provide support to the pelvic floor.[4]

In addition to being an insertion site, it plays a role in providing weight-bearing support to an individual in a seated position in conjunction with the ischial tuberosities.[4] For this reason, increased stress and pressure can be placed on the coccyx while a person leans back in a seated position.[4] The coccyx functions in providing support to the anus.[4]

Postascchini and Massobrio (1983)[5] classified the variations in the morphology of the coccyx into four different configurations:[5]

- Type I: The coccyx is slightly curved forward, with its apex positioned downward and caudally.[5]

- Type II: The forward curvature of the coccyx is more exaggerated, with the apex positioned in a straightforward direction.[5]

- Type III: Sharp angulation of the coccyx forward.[5]

- Type IV: Subluxation of the coccyx at the sacrococcygeal or intercoccygeal joint.[5]

Epidemiology and Etiology[edit | edit source]

Currently, the incidence of coccygodynia is unknown.[4] Certain factors can increase an individual's risk for developing coccygodynia, such as body mass, age, gender.[1][4] With obesity, the coccyx is more vulnerable to increases in intrapelvic pressure while sitting, increasing the risk of posterior subluxation of the coccyx.[1][6] With rapid weight loss, the cushioning around the coccyx may be lost,[4] and the coccyx is at an increased risk for anterior subluxation.[1][6] The risk of coccygodynia is 5 times higher in females than it is in males[4], which may be a result of the increased pressure that occurs during pregnancy and delivery.[7] Furthermore, adults and adolescents are more likely to present coccygodynia than children.[4][6]

Coccygodynia may be classified as post-traumatic, non-traumatic or idiopathic.[3][4] Post-traumatic coccygodynia is usually a result of internal or external trauma.[4] For example, external trauma could result from a backwards fall that might dislocate or break the coccyx,[4][8] and internal trauma could result from a difficult childbirth or a childbirth with an assistive delivery.[4] Minor trauma, such as repetitive sitting on hard surfaces can also lead to coccygodynia.[4][9] Non-traumatic coccygodynia can result from degenerative disc disease, hyper and/or hyper-mobility of the sacrococcygeal joint, infectious diseases and different variations in the configuration of the coccyx.[4] Type II, III, and IV configurations typically cause more pain than type I configurations.[1][5] Furthermore, Postacchini and Massobrio (1983)[5] stated that individuals with coccygodynia are more likely than the general population to have a configuration of Type II and IV.[5] Idiopathic coccygodynia occurs in the absence of any pathology in the coccyx.[1] This is typically a diagnosis of exclusion, and may result from spasticity or other abnormalities affecting the musculature of the pelvic floor.[1] For example, over-extension of the levator ani muscle can shift the coccyx into an abnormal position.[10]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The most common primary complaint of coccygodynia is pain in and around the coccyx without any reports of severe low back pain or radiating pain.[1][2] The pain is typically localized to the sacrococcygeal joint[2] and is described as a “pulling” or “cutting” sensation.[3] Individuals will commonly report tenderness on palpation of the coccyx.[1][2]

Individuals will usually exhibit a guarding seated posture whereby one buttock will be elevated to take weight off of the coccyx.[3] Pain is usually exacerbated with repeated sitting or with transition from sitting to standing position.[1][2] Individuals will report pain is alleviated with sitting on the legs or buttock.[2] Patients may also report pain with defecation or the frequent need to defecate.[1][2] Other complaints may include pain with coughing or increase pain during menstruation in females.[7][11]

Although not a hallmark sign of coccygodynia, low back pain may still arise in individuals with coccygodynia due to the morphological variations in the shape of the coccyx and it’s forward curvature.[1][2][5]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Physical Exam[edit | edit source]

Palpation over the sacrococcygeal joint will display tenderness.[1][3][4] The coccyx should also be palpated to detect the presence of swelling, bone spicules or fragments, and coccygeal masses.[1][2] The soft tissues around the coccyx should be examined for the presence of pilonidal cysts (in-grown hairs).[1][2]

Palpating the coccyx can be used to differentiate between true coccygodynia, which is localized pain over the area of the coccyx, and pseudo coccygodynia, which is characterized by pain that is referred to the coccygeal area from visceral organs, a peripheral nerve, nerve root or plexus.[3] If referred pain is present, pain will radiate around the buttocks, thigh and back and reports of pain with lumbar movements.[7][11] Referred pain may also be indicative of psychogenic coccygodynia, in which pain will be more diffuse and pain will be experience with lumbar and hip movements.[7][11]

Increased pain may also be reported during a straight leg raise test.[7][11]

Upon rectal examination, pain will present when the tip of the coccyx is manipulated. [1][2]An internal mass, referred to as a chordoma, might also be present on the anterior surface of the sacrum.[2]

Imaging[edit | edit source]

Although primarily a clinical diagnosis, dynamic radiographs can be used in diagnosis.[1][2] Dynamic radiographs taken in both sitting and standing positions can provide measurements of coccygeal displacement.[2] Single- position radiographs are usually not used for diagnosis as they are unable to identify any morphological differences between individuals with and without coccygodynia.[1][2][5] Radiographs are usually taken if the pain persists for a duration that is greater than 8 weeks.[2]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Coccyx fracture[3]

- Lumbar spondylosis or disc herniation[3]

- Levator ani syndrome[3]

- Piriformis syndrome[3]

- Descending perineal syndrome[3]

- Perianal abscess[3]

- Rectal tumour or teratoma[3]

- Aclock canal syndrome[3]

- Proctalgia Fugax[3]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Pain Measures[edit | edit source]

- 4-Item Pain Intensity Measure (P4)

- Brief Pain Inventory - Short Form

- Numeric Pain Rating Scale

- Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire

- Visual Analogue Scale

Level of Function in Activities of Daily Living[edit | edit source]

Condition Specific[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Patients with coccygodynia are initially advised to avoid provocative factors. Initial treatment includes ergonomic adjustments such as using a donut-shaped pillow or gel cushion when sitting for a long period of time. This reduces local pressure and improves the patient's posture. There is however no significant evidence that these minor changes reduce the patient's complaints[13].

Mobilizations[edit | edit source]

Mobilizations can be used to help realign the position of the coccyx. The first choice for mobilization is postero-anterior central vertebral pressure (first gently oscillating). Given that there is tenderness to palpation, it might be best to start with rotation mobilization. It is advised to begin mobilizing only one side at one treatment[14].

Another option for manual therapy is to apply Deep transverse frictions (DTF) to the affected ligaments. The patient lies in a prone position with a pillow under the pelvis and the legs in slight abduction and internal rotation. The therapist places his thumb on the affected spot, and, depending on the location of the lesion (direction DTF), the DTF is administered.

Manipulation[edit | edit source]

Manipulation of the coccyx can be performed intrarectal with the patient in lateral position. With the index finger, the coccyx is repeatedly flexed and extended. This is performed for only one minute, to avoid damage or irritations of the rectal mucosa[15].

Massage[edit | edit source]

Massage of the levator ani muscle and coccygeus muscles has also been found to relieve pain[16][17]. To exclude the possibility of muscles pulling on the os coccyx, relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles can be integrated by using biofeedback[18].

Evidence of Physical Therapy Treatments[edit | edit source]

- Stretching of piriformis and iliopsoas muscles and Maitland's rhythmic oscillatory thoracic mobilization for 3 weeks, 5 sessions per week showed significant improvement in pain pressure threshold.[19]

- Extracorporeal shortwave therapy was more effective and satisfactory in reducing discomfort and disability caused by coccydynia than the use of physical modalities. Thus, it was recommended as an alternative treatment option for patients with coccydynia.[20]

- Combined manipulation and corticosteroid injection were more effective in the treatment of Coccydynia as compared to manipulation or corticosteroid injection alone. Patients following the treatment were completely pain free at the end of the year.[21]

- In 16% of the patients (Wray et al) daily ultrasound followed by two weeks of short-wave diathermy (no settings were given) was found beneficial.[15][17]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 Patel R, Appannagari A, Whang PG. Coccydynia. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2008 Dec 1;1(3-4):223.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Fogel G. Coccygodynia: Evaluation and Management. Spinal Cord. 2004;12(1):49-54<article><section> </section></article>

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 Kerr EE, Benson D, Schrot RJ. Coccygectomy for chronic refractory coccygodynia: clinical case series and literature review. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2011 May 1;14(5):654-63.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 Lirette LS, Chaiban G, Tolba R, Eissa H. Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner Journal. 2014 Mar 20;14(1):84-7.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Postacchini FR, Massobrio MA. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1983 Oct;65(8):1116-24.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine. 2000 Dec 1;25(23):3072-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Ombregt L, Bisschop P, ter Veer JH. A System of Orthopaedic Medicine. Elsevier Science Limited, 2003, p.968-969.

- ↑ Schapiro S. Low back and rectal pain from an orthopedic and proctologic viewpoint with a review of 180 cases. The American Journal of Surgery. 1950 Jan 1;79(1):117-28.

- ↑ Pennekamp PH, Kraft CN, Stütz A, Wallny T, Schmitt O, Diedrich O. Coccygectomy for coccygodynia: does pathogenesis matter?. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2005 Dec 1;59(6):1414-9.

- ↑ Maigne R. Douleurs d’origine vertébrale et traitements par manipulations, medicine orthopédique des derangements intervertébraux mineurs, 2e editie, p. 473-476.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Gregory P. Grieve, De wervelkolom, veel voorkomende aandoeningen (The spine), 1984, p. 320-321.

- ↑ CRTechnologies Straight Leg Raise Test (CR) Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=KziCDXXfC-4 accessed on 13/6/19

- ↑ Chiarioni G, et al. Chronic proctalgia and chronic pelvic pain syndromes: New etiologic insights and treatment options. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17(40):4451-4455.

- ↑ Maitland GD, Brewerton DA. Vertebral manipulation. Butterworths, 1973, p.236-239.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wray CC, Easom S, Hoskinson J. Coccydynia: aetiology and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg 1991;73(B):335-8.

- ↑ Thiele GH. Coccygodynia: cause and treatment. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 1963, p.422-436.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Wu C, et al. The application of infrared thermography in the assessment of patients with coccygodynia before and after manual therapy combined with diathermy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009:287-293.

- ↑ Physiotherapist UZ Brussels, internal physiotherapy and gynaecology.

- ↑ Mohanty PP, Pattnaik M. Effect of stretching of piriformis and iliopsoas in coccydynia. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2017 Jul 1;21(3):743-6.

- ↑ Lin SF, Chen YJ, Tu HP, Lee CL, Hsieh CL, Wu WL, Chen CH. The effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy in patients with coccydynia: a randomized controlled trial. PloS one. 2015 Nov 10;10(11):e0142475.

- ↑ Chakraborty S. Nonoperative Management of Coccydynia: A Comparative Study Comparing Three Methods. The Spine Journal. 2012 Sep 1;12(9):S69-70.