Bell's Palsy: A Case Study: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- | '''Original Editor '''-[[Index.php?title=User:Sam Borges&action=edit&redlink=1|Sam Borges]], [[User:Erica Coulson|Erica Coulson]], [[User:Jessica Fieldhouse|Jessica Fieldhouse]] and [[User:Meghan McGrath|Meghan McGrath]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

| Line 199: | Line 199: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Queen's University Neuromotor Function Project]] | |||

[[Category:Case Studies]] | |||

Revision as of 18:45, 15 May 2020

Original Editor -Sam Borges, Erica Coulson, Jessica Fieldhouse and Meghan McGrath

Top Contributors - Erica Coulson, Jessica Fieldhouse, Kim Jackson, Sam Borges, Meghan McGrath, Chelsea Mclene and Shaimaa Eldib

Abstract[edit | edit source]

Bell’s Palsy is a neurological condition involving Cranial Nerve VII characterized by facial drooping and weakness. This is a fictitious case study for educational purposes on Bell’s Palsy involving a 34-year old women, Mrs. S, who was referred to Physiotherapy (PT). Patient reported primary complaints of difficulty drinking without spilling on herself or drooling, headache, pain at right jaw, trouble speaking clearly and right eye dryness. Cranial Nerve VII examination findings found right sided facial droop and drooping at the corner of her right eye and right side of her mouth. The PT intervention included education, facial muscle strengthening exercise, eye protection exercises, modalities and acupuncture. Referrals were made to an optometrist and a speech language pathologist. Following PT intervention, Mrs. S increased her facial muscle strength, with a near complete recovery at 6 months, and was discharged from PT. In the future, more high quality research and evidence is needed to support the role of PT in treating Bell’ Palsy.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

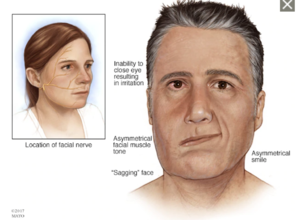

Bell’s Palsy is an idiopathic condition caused by a dysfunction in Cranial Nerve VII (CN VII), also known as the Facial Nerve[1] . CN VII has motor, sensory and parasympathetic components. CN VII innervates the muscles of facial expression, sensory for taste to the anterior 2/3 of the tongue and parasympathetic innervation to the lacrimal gland (tear duct) and most of the salivary glands[2] . Factors that may increase the risk of Bell’s Palsy are diabetes, high blood pressure, toxins, infections (herpes simplex virus 1, HIV, shingles, chicken pox, Lyme disease, Epstein-Barr) and ischemia[3] [4]. Bell’s Palsy can occur at any age, but it is most common between 15-60 years of age, and is believed to be a possible reaction to a viral infections including HSV1, the common flu and shingles that cause inflammation and swelling to cranial nerve VII[5]. Many studies support the use of corticosteroids and eye care to improve the symptoms of Bell’s Palsy[6].[7] However, the evidence supporting PT treatment is less conclusive. There is some evidence that facial muscle exercises can decrease the recovery time but there is a lack of high-quality evidence[7].

This case study describes a patient with Bell’s Palsy who presents with moderate-severe symptoms of facial drooping and weakness on the right side leading to difficulties with drinking, speaking and controlling the muscles of facial expression. This report aims to describe methods for testing and managing Bell’s Palsy and help Physiotherapists create a treatment plan in the absence of high-quality evidence.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Mrs. S is a 34-year old female that was diagnosed with Bell’s Palsy. She was taken to the hospital after her husband thought she was having a stroke due to her right-sided facial droop. The doctors ruled out stroke as a possible option and diagnosed her with Bell’s Palsy, a positive HSV1 test along with having high blood pressure and diabetes helped establish the diagnosis[3].[5] . Mrs. S was prescribed corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and swelling as well as ibuprofen for pain if needed[6] [8] . The doctors recommended PT for her right sided facial weakness. As a result of the right sided weakness Mrs. S complains of trouble with speaking and drinking. Eye dryness has also made it difficult for her to look at a computer for extended periods of time. Mrs. S is a secretary at a law firm and spends 80% of the day sitting in front of a computer screen. She is a mother with a 5-year old daughter and her husband is a fireman.

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

Subjective[edit | edit source]

- Patient Profile: 34 y/o female

- Present Illness: Patient presented to the hospital 2 days ago because husband thought she was experiencing a stroke due to facial drooping on right side. Upon examination she was given a diagnosis of Bell’s Palsy which may be linked to a positive HSV1 test [5]. EMG testing was done to determine the nerve damage and severity[6].

- Past Medical History: Type 2 Diabetes and hypertension; positive HSV1 test[5]

- Medications: Thiazide Diuretics[2], Metformin [9], corticosteroids

- Health Habits: Non-smoker, 3 glass of wine per weeks

- Social History: Works as a secretary at a local law firm. Lives with husband, employed as fireman, and 1 daughter in a 2-story home.

- Patient complaints: Complains of difficulty drinking without spilling on herself and drooling, headache, pain at back of right jaw, reports trouble speaking clearly, which makes it difficult to speak to clients on the phone at work. Complains of dry right eye that worsens over the workday while looking at a computer screen [6].

Objective[edit | edit source]

- Observation: Facial droop on right side, drooping at corner of right eye and right side of the mouth

- CN VII testing: Total tests complete: left side: 6/6 tests completed; right side: 2/6 tests completed.

- Able to lift right side of mouth 0.25cm

- Able to raise right eyebrow 0.5cm

- Able to open mouth

- Able to produce a slight pucker of lips

- Attempted to scrunch face: limitation on right side

- Squinting: could only squint on left eye

- Sensation testing: Taste to anterior 2/3 of tongue intact (Test: cotton swab dipped in salt vs sugar)[10]

- Outcome measure:

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for right jaw pain: at rest: 3/6, after eating or speaking: 6/10

- House-Brackmann Facial Nerve Scale: grade 4 (moderately severe)[11]

- Diagnostic test: Electromyography (EMG) of CN VII[12]

- Functional status: Speech slightly slurred, noticeable effort when talking

- Phase of recovery: Acute (2 days post diagnosis)

Clinical Impression[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

This case presented a patient, Ms. Smith, age 34 with a diagnosis of Bell’s Palsy, who presents with acute right-sided facial muscle weakness and facial droop, dry eyes and functional difficulty with speaking and drinking. Her facial weakness is classified as moderately severe on the House-Brackmann facial nerve scale. The patient’s primary concerns are her jaw pain, her functional difficulties with speaking and drinking and trouble working at her computer due to dry eyes.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The prognosis for Bell’s Palsy has good outcomes generally. About 70% of people will completely resolve without any treatment intervention at all [8].

There is some evidence to suggest that treatment with steroid medication within seven days of symptom onset will result in better outcomes for recovery [13]. It appears that age, gender, side of palsy or comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension do not influence the prognosis or recovery outcomes of Bell’s Palsy [14]. However, the limited and low-quality research in this area poses a challenge in confidently communicating a prognosis to Mrs. S.

Problem List[edit | edit source]

| Body Structure and Function | Activity | Participation |

|---|---|---|

| Pain in right jaw | Unable to drink fluids without spilling | Trouble speaking on the phone a work |

| Right-sided facial muscle weakness | Unable to speak clearly/words are slurred | Unable to work a full day in front of the computer |

| Headache | Difficulty eating hard/crunchy foods due to jaw pain | Challenges with in-person communication due to trouble making facial expressions |

| Dry right eye | ||

| Facial droop on right side | ||

| Drooling |

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Patient goals[edit | edit source]

- Improve House-Brackman Facial Nerve Scale to a grade 2 within 4 weeks from the start of treatment.

- Able to work on the computer for 1 hour without feeling discomfort in her right eye within 4 weeks

- Able to speak for 4 minutes with minimal slurred speech within 4 weeks.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

| Intervention | Frequency | Intensity | Rationale | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eye Dryness | 5 reps every hour | Active Assisted (if needed) | Complains of eye dryness to help with lubrication of the eye and strengthening of the muscles[15]. | |

| AAROM (smile, eyebrow raise, frown, pucker lips, scrunching face) | 10 reps 3 times daily | Isometric hold working up to 10 seconds | Present with muscle weakness, exercises to help strengthen the muscles[15]. | Do exercises in front of mirror for visual feedback. See video examples below. |

| Neuro- proprioception facilitation techniques. (Physiotherapist provides resistance to various muscles of facial expression). | 10 reps 3 times daily | Activate muscles as much as possible. | Help with muscle weakness[16]. | This treatment will be provided once able to active muscle independently. |

| Low Level Laster Therapy (LLLT) | Once per week | 10 J/cm2 for 2 minutes (8 points) | Help with improve function when drinking and speaking[17]. | It has been beneficial in improving facial function[17]. |

| Soft Tissue Mobilization (effleurage) | 2 times per week | 5 minutes (8 points) | Help to improve circulation[18]. | |

| Acupuncture | Once per week | 10 needles 30 minutes | Can help to regulate nerve channels, strengthen resistance to pathogenic factors, increase the excitability of the damaged nerve and promote regeneration of the nerve fibers[19]. | Do on opposite therapy days of LLLT. |

Education [edit | edit source]

Mrs. S will be educated on her condition, potential prognosis and what PT can provide. Eye care education will also be discussed including wearing an eye patch when sleeping to protect the eye[6] and taking a 5-10 minute break from looking at a computer every hour to avoid the eye becoming dry and irritated.

Outcome[edit | edit source]

It was discussed with Mrs. S that the prognosis for Bell’s Palsy is very good and almost full recovery would be expected at 6 months [5] [6] . At the initial visit it was decided that Mrs. S would receive PT 1-2 times a week until her level of functional disability was decreased such that her CN VII testing score was 4/6 and most of her patient goals were met. Once these milestones were met, treatment sessions were reduced to biweekly until she achieved a grade 2 on the House-Bracken Facial Nerve Scale, at which point she would be discharged. After two months of treatment, Mrs. S reported that she had minimal jaw pain (VAS = 0/10 at rest and 2/10 when eating) and no issues with speaking. She presented to the clinic with no resting facial droop. Mrs. S had demonstrated significant improvement in CN VII testing results. She was able to complete 5/6 tasks on the right side compared to only 2/6 at the start of treatment, with some slight difficulty squinting her right eye remaining. Initially, Mrs. S had achieved a grade 4 on the House-Brackmann Facial Nerve Scale, however, after two months of therapy, she scored a grade 2. At this point, Mrs. S was discharged and encouraged to continue with the facial muscle exercises at home until she was back to her baseline function. Knowing that Bell’s Palsy has good recovery outcomes, and that many will resolve on their own, it was not necessary for Mrs. S to keep receiving treatment until she is fully recovered. Referrals were made at the time of initial assessment to a Speech Language Pathologist (SLP) and an optometrist. The SLP would assist with her difficulties in speaking while the PT helps work on her muscular strength of the face. An optometrist would provide assistance with eye care, including lubrication of the eye through drops or medications [3][6].

Discussion[edit | edit source]

Summary[edit | edit source]

This case study presented a 34-year-old female who had an acute onset of Bell’s Palsy causing right sided facial muscle weakness and facial droop, dry right eye and difficulty speaking and drinking. Mrs. S received the diagnosis from a medical doctor who prescribed her with corticosteroids and advised her to seek treatment from a PT. After a full assessment by the PT, she received education about the condition and its prognosis. The PT provided advice to wear an eye patch and to take breaks from the computer to help with her dry eyes. Regarding the facial muscle weakness, the PT prescribed stretching and strengthening exercises to help regain normal muscle function.

Evidence[edit | edit source]

The research around the treatment for Bell’s Palsy shows no significant benefit or harm from PT interventions. Currently, there is some evidence that facial muscle exercises reduce time to recovery[7]. One study showed that there was better improvement on the facial disability scale when LLLT and facial exercises were combined compared to exercise alone (a self-administered study)[17]. It has also been demonstrated that the use of biofeedback when performing the facial muscle exercises (by using a mirror, for example) can be beneficial in developing coordinated muscle activity and preventing synkinesis[15].

However, there is a lack of high-quality evidence and that poses a challenge when creating treatment plans for Bell’s Palsy[8]. Many research studies investigating PT as a treatment for Bell’s Palsy have small sample sizes, short study durations or significant risk of bias in the study design[8]. Additionally, due to the nature of exercise as an intervention, it is hard to create a placebo control group and thus hard to make conclusive statements on the effect of exercise as an intervention for Bell’s Palsy[8]. Furthermore, evaluating the efficacy of any intervention for Bell’s Palsy is especially challenging since ~70% of all cases will resolve spontaneously without any treatment[8].

This demonstrates the need for more high quality RTCs and systematic reviews to guide health care providers in making evidence-based treatment plans for patients diagnosed with Bell’s Palsy.

There is moderate to high quality evidence demonstrating that corticosteroids can be an effective treatment for facial nerve paralysis[8]. Although pharmaceuticals are outside the scope of practice of PT, it is important for practitioners to be aware of this so that they can make appropriate referrals to physicians for patients with Bell’s Palsy.

Self-Study Questions[edit | edit source]

1. Which cranial nerve is affected in a person who has Bell’s Palsy?

a) CN V

b) CN VII

c) CN IX

d) CN X

2. Which of the following is not a risk factor for Bell’s Palsy?

a) Recent viral infection

b) Heavy smoker

c) Diabetes

d) Between the ages of 15 and 60 years old

3. Which of the following has high quality evidence for the treatment for Bell’s Palsy?

a) Acupuncture

b) Manual Therapy

c) Corticosteroids

d) Exercise

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Physiopedia. Bell’s Palsy. Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Bell%27s_Palsy (accessed 8 May 2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mayo Clinic. High blood pressure (hypertension). Available from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/high-blood-pressure/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20373417 (accessed 15 May 2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 John Hopkins Medicine. Bell’s Palsy. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/bells-palsy (accessed 8 May 2020)

- ↑ Zhang W, Xu L, Luo T, Wu F, Zhao B, Li X. The etiology of Bell’s palsy: a review. J Neurol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09282-4

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Mayo Clinic. Bell’s Palsy. Available from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bells-palsy/symptoms-causes/syc-20370028 (accessed 15 May 2020)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Bell’s Palsy Fact Sheet. Available from: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Bells-Palsy-Fact-Sheet (accessed 14 May 2020)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Murthy JMK, Saxena AB. Bell’s palsy: treatment guidelines. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14:S70-S72.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Madhok VB, Gagyor I, Daly F, Somasundara D, Sullivan M, Gammie F et al. Corticosteroids for Bell’s Palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis) (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (2):CD001942

- ↑ Mayo Clinic. Type 2 diabetes. Available from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/type-2-diabetes/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20351199 (accessed 14 May 2020)

- ↑ Newman G. How to assess the cranial nerves. Available from: https://www.merckmanuals.com/en-ca/professional/neurologic-disorders/neurologic-examination/how-to-assess-the-cranial-nerves (accessed 14 May 2020)

- ↑ Physiopedia. House-Brackmann Scale. Available from https://www.physio-pedia.com/House%E2%80%93Brackmann_Scale (accessed 8 May 2020)

- ↑ TeleEMG. Cranial Nerves. Available from: https://teleemg.com/manual/cranial-nerves/ (accessed 8 May 2020)

- ↑ Sathirapanya P, Sathirapanya C. Clinical prognostic factors for treatment outcome in Bell's palsy: a prospective study. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2008;91:1182-1188.

- ↑ Fujiwara T, Hato N, Gyo K, Yanagihara N. Prognostic factors of Bell’s palsy: prospective patient collected observational study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:1891–1895.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM. Physical Therapy for facial paralysis: a tailored treatment approach. Physical Therapy. 1999;79:397-404.

- ↑ Sardaru D, Pendefunda L. Neuro-proprioceptive facilitation in the re-education of functional problems in facial paralysis: a practice approach. Rev. Med. Chir. Med. Nat. 2013;117:101-106.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Ordahan B & Karahan AY. Role of low level laser therapy added to facial expression exercises in patients with idiopathic facial (Bell’s) palsy. Lasers in Medical Science. 2017;32:931-936.

- ↑ Ferreira M, Marques EE, Duarte JA, Santos PC. Physical therapy with drug treatment in Bell palsy: a focused review. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2015;94:331-40.

- ↑ Chen N, Zhou M, He L, Zhou D, Li N. Acupuncture for Bell’s palsy (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(8):CD002914