Ageing and the Cardiorespiratory System

Original Editor - Simisola Ajeyalemi

Top Contributors - Simisola Ajeyalemi, Lucinda hampton, Sai Kripa, Shaimaa Eldib and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Ageing refers to the physiological changes that occur in the human body from the attainment of adulthood, and ending in death. These changes involve a decline of biological functions, and are accompanied by psychological, behavioral, and other changes. Some of these changes are quite obvious, while others are subtle.[1]

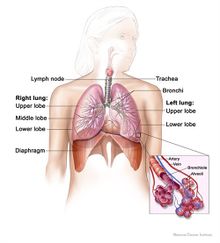

Respiratory System[edit | edit source]

Alveoli coalesce from atrophy and loss of elasticity. Vital capacity is diminished, O2 diffusion impaired and respiratory efficiency reduced. There is reduction of sensitivity and efficiency of self-cleansing mechanism as bronchial epithelium and mucous glands degenerate. Arterial oxygen tension falls from 95mmHg (12.7kPa) at age 30 to 75mmHg (10kPa) at age 60.Osteoporosis affects thoracic vertebrae and rib cage increasing rigidity of the chest wall. There is reduced elasticity and calcification of costal cartilages, weakness of intercostal and accessory muscles of respiration resulting in impairment of functional reserve capacity (clinical evidence is minimal unless evoked by illness). Compliance changes little because the rise to be expected from diminished elastic recoil is offset by increased lung stiffness (fibrosis) and loss of flexibility in chest wall.

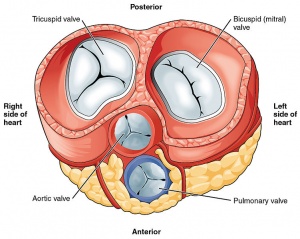

Cardiovascular System[edit | edit source]

Aging decreases the threshold for developing cardiovascular disease. This is essentially due to loss of cardioprotective and compensatory mechanisms that in younger years aide in prevention of cardiac disease development. Changes include:

- Aorta – loss of elasticity plus hyperplasia leads to dilation and unfolding that may obstruct venous return.

- Cusps of heart valves degenerate, with murmurs more detectable, although not necessarily significant.

- Myocardial changes – lipofuscin deposits, myocardial fibrosis and amyloidosis. Atrophy and fibrosis of media, intimal hyperplasia in coronary arteries. This leads to reduced cardiac output (from reduced stroke volume) leading to a given amount of exercise raising heart rate and blood pressure more than in youth.

- Atheroma incidence increases with age, probably promoted by hypertension and cigarettes. Mental confusion and profound weariness should raise suspicion of heart disease in older people. They are often more prominent than angina pain or even breathlessness because of restricted activity.

These ageing changes may lead to Cardiovascular Disease. For example:

- Cardiovascular Disease, the leading cause of death for both males and females.

- Atherosclerosis.

- Arteriosclerosis.

- Coronary Artery Disease.

- Stroke

- Heart Failure[2]

Ageing and Pulmonary Disease[edit | edit source]

Asthma- It is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by narrowing of airways due to inflammation and tightening of the muscles surrounding the airways. Symptoms may include coughing, wheezing, dyspnea and tightness of chest. This condition can be common in both children and adults. The symptoms can be intermittent and usually aggravates with exercise or during night hours. Factors triggering the condition can vary among individuals. The most common triggers include cold, dust, smoke, weather changes, pollen, feathers and perfume. Adults must identify occupational irritants as well as triggers of asthmatic symptoms at home.[2]

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease- It includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema. It is a long term lung disease that makes hard for an individual to breathe. This condition can be asymptomatic in early phases and can lead to death in severe cases. Increase in or overtime exposure to irritants such as smoke can damage the lungs and airways and can cause COPD. Apart, exposure to irritants at work, home and outside can play a significant role in developing COPD. Furthermore, exposure to air pollution, secondhand smoke and dust, fumes and chemicals (which are often work-related) can cause COPD. Patients with COPD frequently exhibit dyspnea, exercise intolerance, decreased health related QOL, and emotional distress.[2]

Pneumonia- It is as an acute respiratory disease primarily affecting the lungs. It leads to inflammation and infection of the lung leading to high fever, shaking chills, and coughs with sputum production or gradually worsening with cough, headache and muscle aches. A number of infectious agents, including viruses, bacteria and fungi, cause pneumonia. [2]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

In people with heart failure, you will need to watch positioning, as they may not tolerate the supine position. Be aware, when treating a chest condition, of the signs and differences between cardiac failure and a chest infection, as we are limited in what we can do with the former complaint compared to the latter.

Circulation- It is important to consider the person’s general sensation and circulation , especially in conditions such as intermittent claudication, neuropathy, Raynaud’s phenomena, and ulceration.

Decreased exercise tolerance and increased fatigue can be secondary to these changes. Your assessment must ascertain the person's prior level of function, so that they can set appropriate goals and progress in a timely fashion. This should also take into account any growing fears, whether chest or heart related, as either will make the individual breathless and anxious about the effect of exercising. You may need to have heart or saturation monitors available during treatment, or at the very least, medications such as GTN spray for angina attacks or inhalers for relief of bronchospasm with chronic respiratory conditions. If conducting a Cardiac Rehabilitation class, ensure you know who is at hand with CardioPulmonary Resuscitation experience.

Watch the work of breathing- it is an indicator of exertion, and ensure adequate recovery time with treatments, whether rehabilitation or of an acute chest problem. There may be an element of acute confusion in those with hypoxia. You may find those with a chronic chest have developed their own coping strategies for breathlessness; don’t ignore these or try to alter them straight away.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Ageing and the Cardiorespiratory System

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1354293/human-aging

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Prevention practice and health promotion, Catherine Rush, 2nd edition, 2014, slack incorporated