Polycystic Kidney Disease

Original Editors - Emily Smith Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems|from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Emily Smith, Vidya Acharya, Elaine Lonnemann, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Admin, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Wendy Walker and Aminat Abolade

Introduction[edit | edit source]

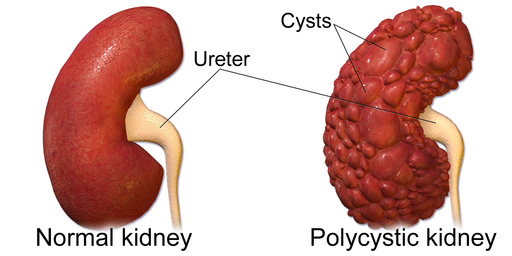

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a genetic disorder that causes many fluid-filled cysts to grow in the kidneys[1]. It's a multisystem and progressive disease with cysts formation and kidney enlargement along with other organ involvement (e.g., liver, pancreas, spleen). Unlike the usually harmless simple kidney cysts that can form in the kidneys later in life, PKD cysts can change the shape of the kidneys, including making them much larger.

In Adults, it is the most frequent genetic cause of renal failure (see Chronic Kidney Disease). Cysts may be detected in childhood or in utero, but clinical manifestations appear in the third or fourth decade of life[2].

Epidemiolgy[edit | edit source]

PKD is one of the most common genetic disorders[1]. Prevalence rates of diagnosed cases ranging from 1 in 543 to 1 in 4000. Approximately 4 to 7 million individuals are affected in the world and account for 7% to 15% of patients on renal replacement therapy. Symptoms usually increase with age. Children very rarely present with renal failure from ADPKD, and disease is slightly more severe in males.[2]

Types[edit | edit source]

The two main types of PKD are

- Autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD), which is usually diagnosed in adulthood

- Autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD), which can be diagnosed in the womb or shortly after a baby is born[1]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms of PKD, eg pain, high blood pressure, and kidney failure, which are basically PKD complications.

In many cases, ADPKD does not cause signs or symptoms until the kidney cysts are a half inch or larger in size.

- Episodes of acute renal pain are seen quite often due to cyst hemorrhage, infection, stone, and, rarely, tumors.

- Urinary tract infection (UTI) is common in ADPKD. UTI presents as cystitis, acute pyelonephritis, cyst infection, and perinephric abscesses[2].

Early signs of ARPKD in the womb are larger-than-normal kidneys and a smaller-than-average size baby ie growth failure. The early signs of ARPKD are also complications. However, some people with ARPKD do not develop signs or symptoms until later in childhood or even adulthood.[1]

Diagnostic[edit | edit source]

Imaging of patients with PKD can be challenging, simply due to the size and number of the cysts and associated mass effect on adjacent structures. It is necessary, to assess all cysts for atypical features, that may reflect complications (e.g. haemorrhage or infection) or malignancy (i.e. renal cell carcinoma)[3].Tests include:

Other tests include:

- Urinalysis can be used to determine if there is blood or protein in the urine. [5]

- Palpation: If the disease has progressed the enlarged kidneys may be palpable upon examination. [5]

- Genetic testing can also be done by taking and comparing a blood sample from the person and three family members who are either known to have or not have PKD. [4]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

There is no cure for PKD, so the best way to manage it is by controlling or minimizing symptoms.

- Controlling blood pressure is one of the most important ways to manage PKD. While it is unsure which blood pressure medications are best for the PKD patient population, many nephrologists agree that ACE inhibitors (Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibitors) or ARB (Angiotensin Receptor Blockers) are good medications to start with.[6]

- Diet, and/or exercise is a good way to slow or prevent the progression of the PKD.[5]

- Urinary infections are common in people with PKD. Prompt administration of antibiotics for the management of kidney, bladder, or urinary tract infections is important for people with PKD as well as drinking plenty of fluids to dilute blood in the urine.[4]

- PKD patients should avoid using all NSAID (Non-Steroidal Anti Inflammatory Agents) due to the negative effects on the kidneys.[6] Patients with PKD may take acetaminophen (Tylenol) for their back and flank pain.[4]

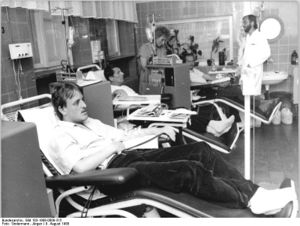

- Dialysis - Those people with PKD who reach end-stage renal failure will need to undergo dialysis treatments and, ultimately, a kidney transplant.[6]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Though there is no cure for PKD, there has been research that shows that exercise can help decrease or manage symptoms on people with chronic kidney disease.

Renal Rehabilitation is an emerging therapy. Many of these studies look at the effect of exercise on the proteinuria, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and blood pressure. One study found that a 12-week aquatic exercise program improved cardiorespiratory functional parameters, resting blood pressure, proteinuria, and the GFR in patients with chronic kidney disease.[7]

Strength Training

Another study looked at the effects of strength training in elderly patients in the predialysis phase.[8] The authors of the study found that after completion of a 12-week exercise program that included resistance training with 60% of the person’s 1 RM, there was no difference in muscle fibre area or fibre type between the exercise group and the control group which was sedentary.[8] However, there were no disadvantageous effects in the histopathology of the muscle in the exercise group.[8] Thus the authors concluded that 60% of the patient’s 1RM is sufficient to build strength and endurance in the patient population but not to increase muscle fibre area or muscle fibre type.[8]

Exercise Program

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials suggested that intradialytic exercise protocols had positive outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients with poor cardiopulmonary function and reduced exercise tolerance and ventilatory efficiency[9].

A third study questioned the number of dialysis patients who might benefit from an exercise program while in the hospital.[10] The authors also looked at the number of patients who adhered to the program as well as the effect of the exercise on the patients’ “10-m shuttle walk test, haemoglobin, body mass index, urea reduction ratio, nutritional status and nine domains of quality of life using the Short Form 36 (SF36) questionnaire”.[10] The results of the study showed that approximately 50% of the hospital haemodialysis patients were interested and able enough to start a dialysis cycling program three times a week.[10] The percentage of the patients that continued the program after 2 months was slightly less than 80% of the starting number.[10] The patients who continued to exercise showed a significant improvement of their walking distance on the shuttle walk test which was correlated with an “improvement in well-being as judged by the quality-of-life scores”.[10] According to the study, “there were no important changes in haemoglobin, nutritional status or effectiveness of dialysis during the 8 weeks of study”.[10]

Dietary Management[edit | edit source]

One way of slowing the progression of PKD is by managing the diet. Many people manage the disease by eating low sodium and low protein diet and drinking lots of fluids. A person with chronic kidney disease may have lab work done to determine which nutrients are and are not being processed properly. With this information, the person may choose to visit a renal dietician to discuss a specific diet customized for the person’s needs.[11] Fluid intake is also important in the management of PKD and should be discussed with a nephrologist. People with PKD lose the ability to absorb water efficiently early on in the disease process. Therefore, a person with PKD may easily become dehydrated during strenuous exercise or extreme heat. A person who is undergoing dialysis must also monitor fluid intake based on the amount of urine produced and the type of dialysis they are using. If the person is no longer urinating, fluid intake should be limited to 1 litre per day.

Researchers suggests potential use of nutraceutical for the treatment of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Several natural compounds, such as triptolide, curcumin, ginkolide B, and steviol (stevia extract) have been shown to be able to retard cyst progression in ADPKD[12].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 NIDDK What Is Polycystic Kidney Disease? Available: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease/polycystic-kidney-disease/what-is-pkd(accessed 4.3.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Akbar S, Bokhari SR. Polycystic Kidney Disease. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532934/(accessed 4.3.2022)

- ↑ Radiopedia Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/autosomal-dominant-polycystic-kidney-disease-1?lang=gb(accessed 4.3.2022)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Mayo Clinic. Polycystic kidney disease. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/polycystic-kidney-disease/DS00245/DSECTION=symptoms (accessed 5 March 2011).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Goodman CC, Fuller KS, Boissonnault WG. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1998.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 PKD Foundation. The Science of PKD.https://pkdcure.org/living-with-pkd/dialysis/ (accessed 5 MaY 2019).

- ↑ Pechter U, Ots M, Maaroos J, et al. Beneficial effects of water-based exercise in patients with chronic kidney disease. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research [serial online]. June 2003;26(2):153-156. Available from: CINAHL with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 5, 2011.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Heiwe S, Clyne N, Tollbäck A, Borg K. Effects of Regular Resistance Training on Muscle Histopathology and Morphometry in Elderly Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation [serial online]. November 2005;84(11):865-874. Available from: Academic Search Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 5, 2011.

- ↑ Andrade FP, Rezende PS, Ferreira TS, Borba GC, Müller AM, Rovedder PME. Effects of intradialytic exercise on cardiopulmonary capacity in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Scientific Reports. 2019 Dec 5;9(1):18470.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Torkington M, MacRae M, Isles C. Uptake of and adherence to exercise during hospital haemodialysis. Physiotherapy [serial online]. June 2006;92(2):83-87. Available from: SPORTDiscus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 5, 2011.

- ↑ PKD Foundation. The Science of PKD.https://pkdcure.org/living-with-pkd/nutrition/

- ↑ Yuajit C, Chatsudthipong V. Nutraceutical for Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Therapy. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand= Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2016 Jan;99:S97-103.