Severity, Irritability, Nature, Stage and Stability (SINSS)

Continuing Editors - Alex Drake and Noah Moss as part of the Arkansas Colleges of Health Education School of Physical Therapy Musculoskeletal 1 Project

Top Contributors - Alex Drake, Noah Moss, Briana Anderson, Chloe Waller, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Sarah Vaughan, Kim Jackson, Aminat Abolade, Madeline Rose, Adrianna Simmons, Kara Nelson and Madison Yokey

Overview[edit | edit source]

The Severity, Irritability, Nature, Stage and Stability (SINSS) model is a clinical reasoning construct to provide clinicians with a structured framework for taking subjective history, in order to determine an appropriate objective examination and treatment plan, and reduce clinical reasoning errors.[1]

The SINSS model helps the physiotherapist to find out detailed information about the patients' condition, filter and group the information, prioritize their problem list, and determine which tests should be used and when. This ensures information isn't omitted and the patient isn't under or over examined and/or treated.[1] The SINSS model is utilized and interpreted from clinical reasoning skills that involve psychomotor, cognitive, anatomical, and affective knowledge from the physiotherapist. Usage of the SINSS model is contextual to a patient's condition and relates perspectives from both the physiotherapist and the patient.[2]

The SINSS model can be an effective tool to compare subjective patient reports and objective examination findings to help determine an accurate diagnosis and the scope of the patient's prognosis through effective clinical reasoning skills. Implementation of the SINSS model during evaluation can aid in understanding of the patient's condition and reduce the risk for clinician clinical reasoning errors.[3] Please note that due to the highly subjective nature of the SINSS model, its' application will vary on a case by case basis. The information and objective findings presented here will only be used to guide the clinician throughout the examination and evaluation process and help relate subjective and objective data from a patient's condition to the steps within the SINSS Model.

The SINSS Model[edit | edit source]

Guidance Through a Case Study[edit | edit source]

To get an accurate representation of how to implement the SINSS model to a patient, subjective and objective findings from a patient's examination will be used throughout this page as it relates to each step of the SINSS model and various steps from the evaluation process.

This patient gave consent to talk about their shoulder injury and how it has impacted their daily life since the original date of onset. A series of questions related to the patients condition were written and the patient filled out the list of questions to the best of their knowledge and ability. These questions were guided through the utilization of information presented by Mark Dutton, PT in which he outlines the clinical examination and evaluation sequence and how subjective information is gathered by the clinician.[4] The highlights of the patient questionnaire and the functional questionnaire results are summarized below:

- Diagnosis of Patient: Partial sub-tendinous tear of the Supraspinatus < 3mm in the Right shoulder, and secondary right shoulder instability and impingement. This diagnosis was confirmed through the utilization of diagnostic ultrasound to the patient's right shoulder.

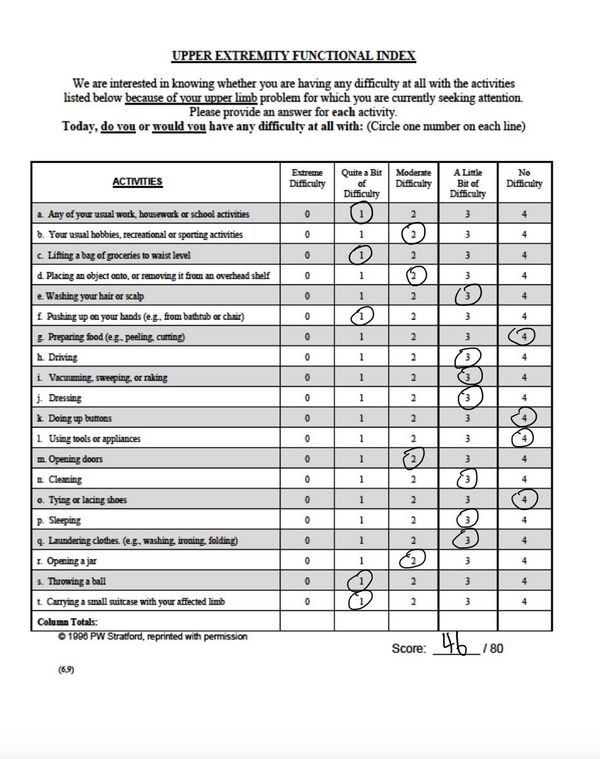

- Functional Questionnaire: Upper Extremity Functional Index (46/80 score).

- Injury Onset Date: 1/24/2024

- Previous injury history: Right shoulder dislocation in 2018.

- MOI: Internal rotation of the right shoulder coupled with a popping noise and pain presence

- Pain: Best- 0/10, Worst- 7/10, Daily average- 2/10 (pain described as sharp pains with movement accompanied with popping and catching and dull aches at rest or when the arm is hanging freely).

- ROM: painful arc passed 90 degrees of abduction, pain with shoulder extension, pain at end range external rotation.

- Functionality: Patient reports compensation and difficulty with activities of daily live (ADLs). Pulling motions aggravate the shoulder joint and increase pain in the posterior shoulder specifically. Patient reports the shoulder feels weak and has not been able to lift more than 3 pounds with the right arm since the onset of injury.

- Subjective information: The patient feels like their injury is improving even if it is slowly. Patient reports seeing progress in both strength and range of motion. The patient states they are limited in their daily life with pain when functioning and a fear of increasing the severity of their injury. Although the process has been hard, the patient stated they enjoy challenging themselves to get better and improve their overall condition.

Severity[edit | edit source]

Severity relates to the intensity of the symptoms, including subjective pain level. Amount, type and pattern of pain should be established. Pain can be measured in a multitude of ways, such as through the visual analogue scale (VAS) and other pain models or pain scales. Using these tools to help gauge the patient’s pain will help assist the clinician in objectively categorizing the symptoms and determining a focal point for treatment. Pain diagrams are beneficial for determining pain location and distribution to better treat a patient's condition.[5] A patient’s perception of their pain can have a great impact on their recovery. A key determinant in the way severity is measured is the extent to which the patient’s activities of daily living (ADLs) are affected, as generally the more severe one’s pain is the more their ADLs are affected.

Considering the patient’s severity includes determining the suitable intensities used for the examination process. Assessing the severity further lends itself to assessing the patients' prognosis and outcome, which supports the therapist in their overall treatment of the patient.[1]

Case Example:[edit | edit source]

A patient is coming with a a diagnosed partial tear of the supraspinatus which is also causing glenohumeral instability and impingement. The patient was a series of questions to determine their "severity" or the effect it has on daily living.

The patient was first asked what their current level of pain on a scale of 0-10 as well as the level of pain at its worst and its best. The patient reported pain as:[edit | edit source]

- Throbbing and sharp pain with sudden movement of the shoulder and sometimes dull aches at rest or when letting the arm hang freely by their side.

- Pain at its best: 0/10

- Pain at its worst: 7/10

- Daily pain on average: 2/10

Pain is a subjective measure that varies from patient to patient but it can help determine the severity of an injury. Generally, pain can be associated with multiple stages of severity classified in the following categories used below.[6]

- Non-Severe: 0-3/10 pain

- Minimally Severe: 4-7/10 pain

- Severe: 8-10/10 pain

It is also important to understand the difference between pain types and how they play a role into staging of an injury.[7]

- Acute pain can be associated with an injury usually surrounding a sudden onset. The type of pain most often described are sharp, shooting, throbbing pains in the affected area. This usually occurs days and up to 6 months after the initial onset date of the injury.[7]

- Chronic pain can be associated with a disease state of pain that is due to an injury that has either improperly healed or has not settled. Chronic pain cannot be attributed to normal, established timelines of recovery and need to be treated differently and adapted with therapeutic intervention.[7]

The patient was then asked, are there any activities or movements that provoke symptoms of pain or irritation?[edit | edit source]

The patient reported that abduction past 90 degrees, shoulder extension, and pushing or pulling with the involved arm irritates their shoulder and increase their pain.

Finally, the patient was asked if their injury had any effects on their normal daily activities.[edit | edit source]

The patient reported that they have trouble with self care, putting on their backpack, and opening/shutting their door to their apartment. These activities can be completed, but they increase their pain and required compensation in order to be completed adequately.

Upper Extremity Functional Index[edit | edit source]

Discussion[edit | edit source]

With this schematic being highly subjective, it means it is left up to the interpretation of the evaluator to determine the level of severity this injury is presenting. Based on the symptoms that are created by daily activities but the patient's ability to still function adequately with the presence of associated compensation causing pain will present as a moderate severity.[1] Moderate severity will moderately inhibit and impact the completion of ADL's and other provoking movements without the presence of pain or compensation.[1] This can have an effect on therapy due to the severity and irritability of the patient's pain, so modification of exercise may be necessary for a successful tolerance to intervention. It is important to consider the highly subjective nature of pain and its' associated severity level. Each patient will perceive levels of pain differently. It is also important to consider the functional level of a patient and how their condition impacts their quality of live and performance of activities of daily living. Communication is paramount when establishing the overall severity of a patient's condition.

Irritability[edit | edit source]

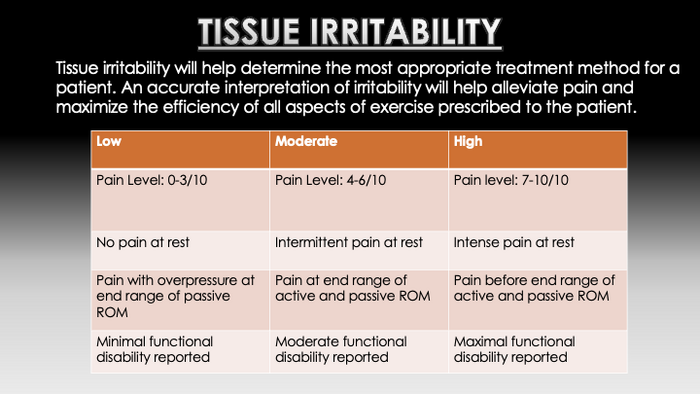

Irritability can be assessed by establishing the level of activity required to aggravate the symptoms, how severe the symptoms are and how long it then takes for the symptoms to subside.[8] Irritability can be determined by different symptoms including pain level, pain at rest, where the pain is felt during joint movement, and functional level of the patient. Irritability can also be judged by the ratio or aggravating factors to easing factors.[9] The concept of tissue irritability was initially proposed by Maitland as the tissues ability to handle physical stress, however, there are not widely used, reliable, or valid classifications for irritability.[10] Irritability mainly focuses on certain movements, stresses, or activities that aggravate or irritate a patient's injury or condition and relate those irritating factors to things that alleviate or relieve them. It is important to understand how and why certain things can flare up and irritate a patient's condition and keep those activities to a minimum in order to effectively treat a patient's condition.[6] It is also beneficial to the patient to understand how to adequately alleviate irritating symptoms to promote recovery and relieve any pain that may be present before, during, or after treatment. The clinician should also consider the patients' irritability when planning the evaluation and subsequent interventions.[6] This understanding helps the clinician provide the most effective treatment. The clinician should also consider the extent to which they challenge the patient as this helps by preventing unnecessary exacerbation of a patients' symptoms.[1]

Case Example:[edit | edit source]

The same patient that was asked questions about the severity of their condition was also asked about the irritability of their ailment. Following this are the questions that were asked as well as the answers they gave.

Do you have any pain when moving through range of motion? If so, when does your pain occur?[edit | edit source]

This question is primarily looking for a painful arc and what movements may make the symptoms worse.

The patient responded as such, “ pain at 90 degrees of abduction, pain at 40 degrees of Glenohumeral(GH) extension, and pain at the end range of GH external rotation.”

Note: There is another evaluation step within this question that would alter the irritability assessment which was the end feel of these movements. The end feel is normally determined in order to evaluate the integrity of the joint, but in this case the end feel could not be evaluated due to the pain accompanying the movements. These questions were evaluating the tissue reactivity of the patients ailment which ultimately could not be determined, but aid in assessing irritability through functional measures.

Does pain ever inhibit normal functioning of your affected joint? If so does it completely inhibit function, impair the completion or is compensation required, or is there no pain with activity?[edit | edit source]

This question seems to be extensive, but it is looking at the patient's ability to complete tasks and how pain may limit the functionality of task completion. This is called:

Functional reactivity

It is up to the evaluating practitioner to determine the patients functional reactivity via their response with the example patient. The patient responded as such, “ I have had to change the way I perform some ADL’s to avoid pain.” The patient reported having to change their way of living with everyday tasks such as personal hygiene, self care tasks, putting on a backpack, and opening or shutting doors. The patient also stated feeling "apprehensive" and "cautious" when moving their shoulder quickly to avoid furthering their injury.

Are there certain movements or positions that make the pain worse? Is there a certain location that if provoked or moved too much, would it cause an increase in pain or symptoms?[edit | edit source]

These questions are used to determine the next evaluation step of irritability which is determining:

Aggravating factors

The patient responded to these questions as such; “ pushing and pulling. Pulling makes it worse.” They also said “I have pain in the posterior portion of my right joint capsule if I move too much or too quickly.” These movements provide more insight into how the patient's injury can be provoked. The general location of pain can also help a clinician gain insight into what actions could be harmful or irritable to the patient using the muscle action(s) of the muscles surrounding the painful area. These actions should be avoided in the presence of an increase in pain. Motions or actions that cause an increase in tissue irritability can further hinder a patient from performing functional tasks without pain or compensation.

Discussion[edit | edit source]

The patient in this case example was determined to have a moderate irritability due to the presence of pain with activities of daily living and marked compensation required to complete them. This was also determined by the fact that pain can be alleviated through conventional means such as ice and resting, Again it is up to the evaluating practitioner to take all of the questions and responses into account to determine the overall irritability of the patients condition. These determinations may also influence what kind of exercises and treatment methods are provided to the patient when moving forward with treatment. The interventions provided to the patient should be determined by pain level, functional level of the patient, and the patient's overall goals and needs related to their condition. For example, if you determine the patient has a high irritability, you may start the patient off with more conservative treatment exercises or modalities and vice versa.[11] Irritability of a patient's condition will have a direct affect on how treatment is provided and proceeds throughout the rehabilitation process. It is important for clinical reasoning knowledge to be utilized and communication between the clinician and patient to occur in order to minimize the irritability of a patient's condition.

Nature[edit | edit source]

Nature is a broad term relating to the patient's diagnosis, the type of symptoms and/or pain, personal characteristics/psychosocial factors, as well as red and yellow flags related to the pain a patient experiences associated with a particular medical condition. Within this category, a clinician should be able to recognize if the condition is within their scope of practice, as well as if the condition requires immediate action or special considerations.[1] Pain can also be an accurate indicator for differential diagnosis and can aid in determining the proper diagnosis and treatment methods to utilize.[1] Clinicians can accurately predict a patient's diagnosis by utilizing evidence based practice principles along with good clinical reasoning skills.[12] The type of pain is important when discussing a diagnosis of a condition and the level of pain that is experienced by the patient dictates how treatment should proceed. Clinicians should use a patient centric approach when examining and treating patients. This is due to the unique experience of pain and how it is perceived differently from patient to patient. Pain encompasses many different aspects of a patient's life including psychosocial factors, environmental factors, personal factors, cultural beliefs, generational factors, and their own pain tolerance.[1] The nature of a patient's pain can help determine a diagnosis, how well they may respond to treatment, and gives insight into how the patient views and perceives their condition personally.

Case Example:[edit | edit source]

The following questions focus on the patients pain or abnormal feelings within the patients involved joint. The following are the questions to determine the nature of the patient's condition, as well as the patients response to therapeutic intervention.

What is the general nature of your pain if present? If present, about how long does you pain last?[edit | edit source]

The patient responded as such; “sharp and dull aches,” “the pain usually lasts a few minutes”

These questions are focusing on the type of pain and the length of time the patient's pain usually lasts. This will not only aid in determining aggravating and alleviating factors, but also how the pain may affect the patient and how long they perceive and/or tolerate their pain.

When moving, do you experience any unnatural noises or feelings in your affected joint? If present, where is the majority of your pain? Does it radiate or is it in a specific spot?[edit | edit source]

The patient responded as such; “Popping and clicking,” the patient also states, “my pain stays in either the front or back of my shoulder." This will give the clinician insight into where the pain the patient perceives arises. This question can help determine a focal point for a diagnosis and help aid in an accurate treatment plan to help alleviate some of the patient's pain. The lack of radiation also means this isn't necessarily a nerve related issue but more a musculature issue.

Discussion[edit | edit source]

These questions focus on the pain that occurs from their condition and how it can be interpreted by the clinician as it relates to the patient's overall condition. The description of the pain is highly subjective and can differ from patient to patient, so the understanding of the patients view on pain is needed in order to completely understand how much pain the patient is experiencing. The interpretation of these questions and the patients pain is also subjective, there is no cut and dry method of determining the patients nature of pain, but the evaluation can that pain can provide information for other sections of the model such as the severity of the injury, as well as the stage. It is important to effectively communicate to get a full scope of how the patient's pain limits them, how it can alleviated and managed, and how severe the pain is currently and how it fluctuates on a daily basis.[6]

Stage[edit | edit source]

Stage refers to the duration of the symptoms. Stage can be a useful to consider the inflammatory process and/or stage of healing. Every patient does not necessarily experience every stage of healing, nor is healing confined to these specified stage timeframes. The clinician may need to take into consideration a settled phase that occurs after the subacute phase and before the chronic stage is reached.[13] The stages of tissue healing coincide with various degrees of inflammatory processes and cellular tissue repair.

Stage classifications:

- Acute: typically days-weeks (<3 weeks), inflammatory processes are most active during the acute stage and are typically accompanied with changes in vasculature, clotting formation, and phagocytosis.[1]

- Subacute: typically weeks (3-6 weeks), tissue proliferation and remodeling are present during the subacute stage where tissues are growing new capillaries, new collagen is reforming around the affected area, and growth of granulation tissue is present. The tissues are very fragile during this stage. The affected area must be handled with extra care and caution as the area heals and scar tissue/collagen lattice forms.[1]

- Chronic: typically weeks-months (>6 weeks), the chronic stage of healing is characterized by tissue remodeling, maturation, and collagen tissue contraction. Movement is extremely important during this stage due to collagen aligning with the direction of force. Since the collagen has healed, this stage usually incorporates more vigorous exercise and strengthening of the affected tissues.[1]

- Settled: This stage usually occurs between the subacute and chronic phases. This phase is characterized by a "settling" of the injury and complete healing has occurred before the condition can progress into a chronic one. This typically takes place between 4-6 weeks before a chronic stage of healing can be classified.[13]

Case Example[edit | edit source]

The stage of healing questions are focused on how much pain is being experienced, how the patient feels about the integrity of the joint, and what potential stage of healing the injury is in.

Do you have an of the cardinal signs present in your affected joint? Generally, how would you describe the strength of your affected joint? When was the onset of injury?[edit | edit source]

The patient responded to these questions as such; “pain in the front and back of my shoulder, specifically after exercising my shoulder” “I would say I’m very weak in my right arm (the affected arm), I have not been able to lift weights without pain since my injury, but recently I have been able to lift a 3 lb weight without pain.” “ Since my injury was almost 2 months ago, I would say I am in the chronic phase of healing.” The patient gives very good insight here to their condition now compared to the initial onset of injury. The patient has been recovery for over 2 months now, they have been feeling stronger and are making progress in strengthening, and the patient still feels pain especially post exercise. The patient also has no inflammation or swelling present in the shoulder. This subjective information can accurately group the patient into the chronic phase of healing.

Discussion[edit | edit source]

The answers of these questions will depend on the type of pain, and general extent of healing. The patient may not know what the difference between chronic, subacute, and acute means so, it is up to the practitioner to determine the amount of healing that has occurred and explain the stages of healing to their patient. The stage of healing will aid in determining the most appropriate, effective, and evidence based treatment for a patient's condition.[1]

Stability[edit | edit source]

Stability refers to how the symptoms are progressing or regressing, which the clinician can use within the wider context of subjective and objective information to evaluate the effectiveness of their assessment and treatment, and guide progression or regression of interventions.[14] Stability of a patient's condition can be considered evolving and may change at any point during rehabilitation depending on how a patient reacts to treatment intervention because stability is related to a current episode of a condition or all known episodes related to a patient's condition.[1] Stability of a condition can generally follow different stages of healing, but this is not finite and should not always be relied upon. The condition can be classified as any of the following:

- Improving: Symptoms should decrease in intensity, frequency, and location. Regular movement and functioning should be returning. Regular sleep patterns may be restored or restoring. Patient's are less dependent on regular usage of pain medication.[1]

- Worsening: Symptoms may increase in intensity, frequency, and location. There is an overall regression in movement and functioning of the patient. Sleep patterns may be disrupted and sleep adequacy is decreased. Pain medication dependence for pain relief may increase.[1]

- Not changing: Intervention may not be having the intended affect on a patient's condition. Symptoms do not change, they are stagnant and do not get better nor worse. Progression is halted and no therapeutic affect is detected. No noticeable changes in sleep patterns or pain medication dependence. [1]

- Fluctuating: The overall condition can be dependent on different things such as patient's psychosocial thoughts and behaviors, external factors, time of day, and biophysical considerations. At times, the condition may seem like it is improving, and other times it may seem as though a patient's condition is worsening. The patient's condition cannot be grouped into one of the above categories adequately due to the ever-changing nature of the condition as it fluctuates.[1]

Case Example[edit | edit source]

The psychosocial aspects of an injury are important to consider when implementing effective treatment and patient care.In this example, the patient was asked about their thoughts and feelings related to their condition. The patient was also asked about their quality of life and level of functioning now compared to before the onset of their injury.

Do you feel your injury is improving, staying the same, or getting worse? How do you feel overall regarding your injury?[edit | edit source]

The patient answered these questions as such; “I feel that my injury is getting better. It has been a slow process, but I am starting to see progress.” They then said this for the second question, “I feel that my injury is holding me back in some ways. I have trouble finding ways to be able to perform tasks for school without pain and without the chance of making the injury worse. I have enjoyed challenging myself with doing research and finding what rehabilitation exercises will benefit me the most. It’s a very slow process, but I am finally starting to see improvement in pain, ROM, and ability to lift weights.”

Discussion[edit | edit source]

The objective when asking these questions, as previously mentioned, is to evaluate how the patient feels about the treatment process, and the situation as a whole. Some different interventions may be thought about based on how the patient feels; in this example you may be able to challenge the patient more than initially thought due to their appreciation of the challenge of researching different exercises. Just like the rest of the model, this section is subjective and depends on the practitioners interpretation of the answers and questions asked. Stability is not clear cut and depends mainly on the subjective nature and perception of a condition from the patient. The clinician should engage the patient actively to help promote stability of a patient's condition through proper education, engaging exercise, making therapy a calming environment, and discussing any negative impacts that the patient might be feeling regarding their condition and rehabilitation. It is important for the clinician to keep reassessing progress that the patient is making and determining the overall progress that therapeutic intervention is having on their patient's condition.[1]

Limitations[edit | edit source]

The SINSS model does have limitations when it comes to diagnosis and prognosis of a patient's condition. Since the SINSS model is highly subjective, examination findings and clinical reasoning skills will differ and be implemented differently for each individual physiotherapist. In totality, the SINSS model cannot be used solely to determine the diagnosis of a patient's condition or injury. In the case example that was used throughout this page, the SINSS model was used to find and organize subjective and objective findings from the patient. The actual diagnosis of a supraspinatus tendon tear was ultimately confirmed through the utilization of diagnostic ultrasound.

The focal point of this section is to underline the fact that the SINSS model alone cannot diagnose a health condition. The reason for implementation of the SINSS model is to collect subjective data the patient reports and objective findings from the examination and using clinical reasoning skills to relate the collected data to a suspected diagnosis[1],[4]. The SINSS model coupled with imaging can create and confirm an accurate diagnosis related to a patient's condition. Examination findings relating to the SINSS model can then be used further to get an accurate picture of the prognosis for a patient's condition once a diagnosis is confirmed through imaging.[6]

Tying it Together[edit | edit source]

Although the SINSS model cannot alone diagnose health conditions, it can be used as a vital tool to aid in the examination and evaluation process of a patient's condition. In the case example, a full scale examination and evaluation was not utilized, but a custom written health questionnaire was incorporated to compile subjective and objective data related to the patient for example purposes. The patient's responses to the questions provided gave insight into where to the clinician's focus should be within the affected joint. A diagnostic ultrasound was ultimately performed on the patient and through the results from the ultrasound imaging, coupled with the subjective and objective findings relayed by the patient and found by the clinician, can accurately confirm a diagnosis. Once a diagnosis is established, information gathered from the patient and from the clinician portray a prognosis about a patient's condition. Factors such as pain, irritability, and evolving stability of a condition can all play a role into how rehabilitation will be initiated and proceed.

Through the examination and evaluation process, the patient reports subjective information and the clinician uses this information and clinical reasoning skills to appropriately examine, evaluate, and intervene to provide quality treatment and care for a patient's condition. It is imperative that a clinician uses clinical decision making skills to work collaboratively with their patient during the rehabilitation process by: providing an emphasis on the importance of proper movement and biomechanics related to their condition, explaining a broad picture of the patient's condition related to their diagnosis and prognosis, and how the patient and clinician can work collaboratively by gaining insight into the psychosocial aspects of their condition and subsequent treatment.[4]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

There are multiple models of clinical reasoning. SINSS presents a methodical approach that can benefit the clinician and the patient, by allowing the clinician to gain a deeper understanding of the patient's experience which can result in more appropriate interventions.[1] Additionally, the SINSS model can be beneficial in education when utilized by mentors and their students to help facilitate the clinical reasoning process.[1] While utilizing the SINSS model in the orthopedic setting may reduce clinical reasoning errors during the diagnostic and prognostic process as well as the intervention[1], the SINSS model requires further research to confirm that its use improves patient outcomes.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 Petersen EJ, Thurmond SM, Jensen GM. Severity, Irritability, Nature, Stage, and Stability (SINSS): A clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2021 Oct;29(5):297-309

- ↑ Huhn K, Gilliland SJ , Black LL, Wainwright SF, Christensen N. Clinical Reasoning in Physical Therapy: A Concept Analysis. Physical Therapy. 2019 April; 99(4): 440–456

- ↑ Petersen EJ, Thurmond SM, Jensen GM. Severity, Irritability, Nature, Stage, and Stability (SINSS): A clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2021;29(5):297-309.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Dutton, M. Examination and Evaluation: In: Weitz M, Boyle PJ, editors. Dutton's orthopaedic examination, evaluation, and intervention. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2020. p. 163-214.

- ↑ Southerst D, Cote P, Stupar M, Stern P, Mior S. The Reliability of Body Pain Diagrams in the Quantitative Measurement of Pain Distribution and Location in Patients with Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2013 Sep; 36(7): 450-459.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Dutton, M. Dutton's orthopaedic examination, evaluation, and intervention. 5th ed. NY: McGraw Hill Education; 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Grichnik KP, Ferrante FM. The difference between acute and chronic pain. Mt Sinai J Med. 1991;58(3):217-220.

- ↑ Barakatt ET, Romano PS, Riddle DL, Beckett LA. The Reliability of Maitland's Irritability Judgments in Patients with Low Back Pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(3):135-40.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kelley MJ, Shaffer MA, Kuhn JE, Michener LA, Seitz AL, Uhl TL, Godges JJ, McClure PW, Altman RD, Davenport T, Davies GJ. Shoulder pain and mobility deficits: adhesive capsulitis: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2013 May;43(5):A1-31.

- ↑ Kareha SM, McClure PW, Fernandez-Fernandez A. Reliability and Concurrent Validity of Shoulder Tissue Irritability Classification. Phys Ther. 2021 Mar 3;101(3):pzab022.

- ↑ Barakatt ET, Romano PS, Riddle DL, Beckett LA, Kravitz R. An Exploration of Maitland's Concept of Pain Irritability in Patients with Low Back Pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):196-205.

- ↑ Rhon DI, Deyle GD, Gill NW. Clinical reasoning and advanced practice privileges enable physical therapist point-of-care decisions in the military health care system: 3 clinical cases. Phys Ther. 2013;93(9):1234-1243.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Baker SE, Painter EE, Morgan BC, Kaus AL, Petersen EJ, Allen CS, Deyle GD, Jensen GM. Systematic Clinical Reasoning in Physical Therapy (SCRIPT): Tool for the Purposeful Practice of Clinical Reasoning in Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapy. Phys Ther. 2017 Jan 1;97(1):61-70.

- ↑ Koury MJ, Scarpelli E. A manual therapy approach to evaluation and treatment of a patient with a chronic lumbar nerve root irritation. Phys Ther. 1994 Jun;74(6):548-60.