Myalgic Encephalomyelitis or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Definition[edit | edit source]

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)[1] is a complex, chronic, multi-system disease that significantly impairs one’s function and quality of life.[2]

Description[edit | edit source]

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) has been classified as a neurological disease by the World Health Organization since 1969 .[3]The hallmark symptom noted with ME/CFS is known as “post-exertional malaise” (PEM), which can occur after physical, cognitive, or emotional exertion. PEM may occur at levels disproportionate to the apparent level of exertion and does not subside with rest, as it would restore any other individual without ME/CFS to a pre-activity baseline.[4] The resulting PEM is what sufferers call a "crash". PEM and/or a “crash” can begin immediately upon exertion or hours to as many as seven days post-exertion. Recovery to pre-exertion baseline can take hours to months, and in some cases, the patient never recovers to the pre-exertion baseline.[5]

ME/CFS affects as many as 24 million people worldwide[6], between 836,000 and 2.5 million in the USA[7], 580,000 in Canada[8], 250,000 in Australia[9], and 260,000 in the UK.[10] The effects of the illness are spectral in nature with approximately 25% of sufferers considered severely affected, lacking the ability to do the most basic ADLs such as feeding, toileting, bathing or independent standing.[11] The remaining 75% may live life tethered to strict regimes of energy conservation that enable them to continue working at minimum, or just barely maintain independence with ADLs and IADLs.

75% of all individuals with ME/CFS are unable to work.[12]

Quality of life (QoL) studies show that ME/CFS patients report lower QoL scores than individuals with stroke, cancer, heart disease, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis.[13] Similar findings were reported following the comprehensive Wichita Clinical Study, conducted in 2002-2003 in which the intent was to, “characterize the physiological status of subjects with CFS [ME/CFS]”. The primary author, William Reeves, MD stated in 2006 at The National Press Club, “...We’ve documented, as have others, that the level of functional impairment in people who suffer from CFS [ME/CFS] is comparable to multiple sclerosis, AIDS, end-stage renal failure, [or] chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The disability is equivalent to that of some well-known, very severe medical conditions.[14]”

ME/CFS disproportionately affects females at a rate two to four times that of males, but there is no discrepancy between ethnicities or socioeconomic groups.[15]There are two peaks of incidence in ME/CFS with the first in the teenaged years and the second in individuals 30-35 years of age[16]. Studies report the diagnosis of children as young as 2 years old[17], and a recent study showed an under-diagnosing of children in a community-based sample ages 5-17.[18] Due to lack of professional training about the disease (less than 30% of all medical schools in the USA address ME/CFS at all)[19], and the typical 1-5 year time period to get diagnosed[19], it is likely children are affected much more frequently at younger ages than the majority of studies are capturing.

ME/CFS significantly impacts the ability of children to attend school. One study found 90% of affected students missed 15-50% of all school days in a six-month period[19], and a UK study found “...ME/CFS to be the primary cause of long-term health-related school absences.”[19] From a financial standpoint, the cost of ME/CFS is staggering - calculated between $36 and $51 billion dollars (US) in 2021.[20]

The lack of professional training about the disease is not entirely surprising, given the historical misunderstanding of what ME/CFS is, the current inability to identify diagnostic biological markers, the lack of effective treatments, and lingering controversy of whether the symptoms are even representative of a unique clinical disease or possibly several overlapping illnesses. Originally considered to be a form of epidemic neuromyasthenia, it has also been identified as atypical poliomyelitis[21], chronic fatigue immune dysfunction syndrome, Tapanui flu, Akureyri disease, low natural killer syndrome, and most recently, post-viral fatigue syndrome, and systemic exercise intolerance disease.[22] For many years, misdiagnosed ME/CFS patients have been dismissed, undertreated, viewed as suffering from psychological rather than physical disorders, and have received inappropriate and frequently dangerous treatments, such as graded exercise therapy (GET) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that have exacerbated their conditions or falsely blamed the patients when they, in fact, have a biomedical condition.

Additionally, there is constant confusion between “chronic fatigue” that plagues many individuals in our busy, modern world and “chronic fatigue syndrome” - the disease - which has far more complex symptomatology, comorbidities, and potentially long-term consequences for health and functionality. Failure of medical personnel to distinguish appropriately between the two can affect approach and attitudes toward both patient groups, but can greatly impact the ME/CFS patient’s diagnosis, plan of care development and implementation, access to appropriate referrals, legal/clinical documentation paper trail, medical coding/insurance, and the ability to qualify for necessary supplemental financial support programs including both governmental and private disability programs.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Because ME/CFS is a spectral disease, patients on one end of the spectrum may appear visibly “healthy”, for all intents and purposes. In fact, it is one of the conundrums of the disease how well patients can look despite how physically ill and functionally impaired they are. This misconception that a patient could not possibly ‘look so well’ and still be as physically ill as they report to be has led to frequent misdiagnosis and underestimation of the severity of the illness, especially with clinicians unfamiliar with ME/CFS. On the other end of the spectrum, however, are the ME/CFS patients who are clearly, visibly, very ‘unwell’, often severely emaciated or morbidly obese, who are rarely seen in medical or therapy offices due to the challenge of expending energy for travel and their level of medical fragility.

Most health providers have never seen a severely affected ME/CFS patient in person unless they provide home health services or possibly are involved in the periodic changing of feeding tubes or ports. Some of these individuals live for years or even decades in darkened, noiseless rooms, without human touch due to the impact sensory stimulation has on their nervous systems, unable to move due to weakness, vestibular, and other neurological complications. They lack even the most basic health services in most cases, often relying on family members who have learned to care for them through trial and error as the illness engulfed their loved ones.

Patients present with a myriad of symptoms that impact multiple organ systems. Patients commonly have orthostatic intolerance issues that result in dizziness and lightheadedness/vertigo, abdominal symptoms including nausea, pain, and sensory processing issues that result in headache, photophobia, hyperacusis, joint and muscle pain (without erythema or edema), and fatigue that is very distinct and different from mere somnolence. This fatigue is frequently described in some metaphoric relation to "feeling like moving through wet cement", or “having lead poured in my limbs.” Most patients also report some form of neuro-cognitive impairment including deficits in short-term memory, decreased ability to multi-task, inability to process information, "brain-fog", difficulty reading, and even watching television.[23] It is not uncommon for patients to experience flu-like symptoms including swollen neck and axillary glands and sore throat, especially during the early phase of the illness.[24]

Thermoregulatory issues, misophonia, muscle weakness, and insomnia can also be issues for these patients. Patients' sleep is often disrupted with sleep schedules frequently flipped, and despite their often profound fatigue, often cannot fall asleep, feeling instead, "wired" and agitated, while other patients sleep for long periods of time. Both groups typically awaken feeling as if they have had no restorative sleep at all.

PEM, the hallmark feature of this disease is the exacerbation of any of these symptoms (or others) following physical, cognitive, or emotional efforts. Most patients live with some level of symptomatology at all times, but it is the PEM that is so profoundly disabling and overwhelming to the patients as it strips away virtually all sense of personal control of patients' lives.

Dialogues for ME/CFS is made possible with a reward from the Wellcome Public Engagement Fund. Click https://www.dialogues-mecfs.co.uk/ for access to additional scientifically-based videos on ME/CFS.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Presently, it seems ME/CFS may have many potential contributing causes that involve multiple body systems including the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems.[26] Although not all patients with ME/CFS can identify a known trigger, many patients can identify the specific day in which their lives changed and what event or triggering factor appears to have played a role in their illness onset. Many of the proposed disease models are consistent with patient reports of the disease starting with central nervous system (CNS) damage that may be precipitated by infectious agents, toxins, physical or psychological stressors.[26] The damage to the CNS then is thought to be the cause of altered immune and endocrine function.[26] It is very common to hear something to this effect from a ME/CFS patient, “I got sick with a very bad flu and simply never got better.”

Research has shown abnormal brain EEG, reduced brain blood flow, reduced gray matter volume, altered metabolic findings, and abnormalities concerning the areas of the brain that regulate stress, energy production, concentration, motivation, fatigue, and pain.[26]

Immune system abnormalities that some ME/CFS patients have included two enzyme changes that may impact the ability of ME/CFS patients’ immune systems to seek, identify, and kill pathogens that have infected them. These are the RNase L antiviral enzyme and the protein kinase R (PKR) enzyme.[26] Another immune impairment also found in some ME/CFS patients is low numbers and poor functioning of natural killer cells and poor T-cell function. Again, this deficit results in the immune system being less adept at finding and killing pathogens.[26]

Some ME/CFS patients have been shown to have Th1/Th2 imbalances. Th1 is a pro-inflammatory agent and is underactivated in some of the ME/CFS population while Th2 is an anti-inflammatory agent and is overly active in this population resulting in increased allergen and sensitivity problems and decreased response to pathogens.[26]

Other studies indicate that some ME/CFS patients may be suffering due to undiagnosed or reactivated chronic infections with current attention being focused on herpesviruses and enteroviruses.[26] Antiviral drug studies have been tried with the most recent, rituximab, showing no positive impact on the illness.[27] Other antivirals such as valacyclovir and valganciclovir have been shown to be effective if used long-term in a specific subset of ME/CFS patients.[28]

Many ME/CFS patients have an impaired hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response with low cortisol levels. This may have an impact on the ME/CFS patients' fatigue levels as impaired HPA interferes with the mobilization of energy stores within the body. Low HPA activation may also play a role in chronic immune disruption which can manifest in ME/CFS patients as increased immune/inflammatory responses to stimuli.[29]

The imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activation may also be a contributor to symptomatology for some patients. The increased sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation results in narrowed blood vessels, decreased blood volume, decreased brain and muscle perfusion, heart abnormalities under stress, and decreased parasympathetic activation resulting in poor quality of sleep all of which have been identified in the ME/CFS population.[30]

Lastly, there is a reported genetic component to the disease with several neuroendocrine and immune mutations identified in the disease. ME/CFS, like many other complex diseases, likely has many genetic contributors which individually are minor disruptors, but in the aggregate are significant contributors to the systems-wide disruption that manifests as widely observable and reported symptomatology.[31]

A more detailed summary of current research into ME/CFS, including possible causes, can be viewed at MeAction’s, 2019 ME Research Summary by following this link: https://www.meaction.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/19_MEA_Revised_2019_Research_Summary_190610.pdf[32]

Diagnostic Tests/Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Key Points in Considering an ME/CFS Diagnosis[33]

- A child or an individual who has symptoms of fatigue and non-refreshing sleep for more than three months which cannot be explained by or linked to any other physical/mental illness.

- When available, refer the patient to a ME/CFS specialist team, who specializes in assessing, diagnosing and treating ME/CFS. Currently, there is no diagnostic test for ME/CFS.

- This team of specialists may include, primary and speciality physicians, physical therapist, occupational therapist, exercise physiologist, speech therapist, nutritionist, and a counselling psychologist.

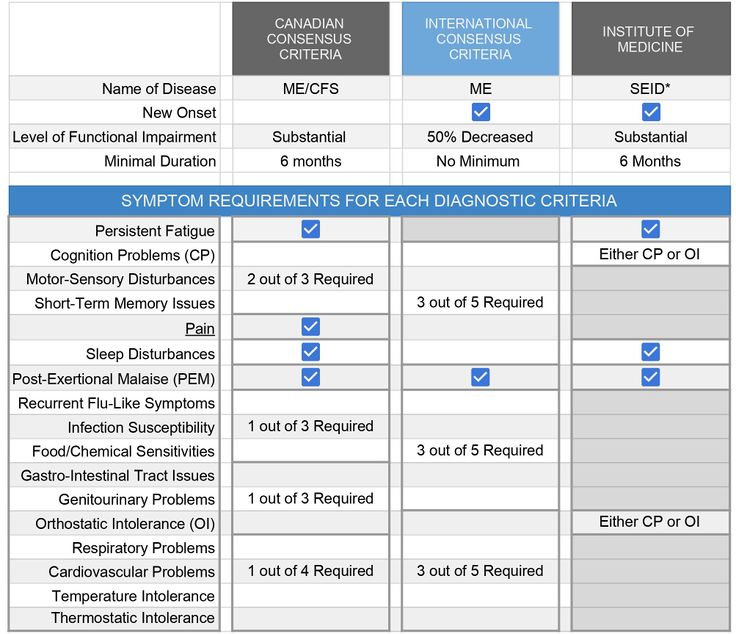

Diagnosis is made using clinical case criteria which help the diagnosing clinician determine whether the patient in question meets the established criteria for the disease based upon a current pathophysiological understanding of ME/CFS. Over time, various case criteria have been used for research and clinical purposes. The Fukuda Criteria, 1994 is largely relegated to research when utilized and is increasingly criticized when used because of its broad inclusion characteristics.[34] Currently, these are the most common for clinical diagnosis: International Consensus Criteria, 2011 (ICC)[35], Canadian Consensus Criteria, 2003 (CCC)[36], NICE, 2021 (UK)[37], and Institute of Medicine, 2015 (IOM).[38]

Despite the plethora of evidence that ME/CFS is a biological illness[38], until fall, 2021, there had remained a divide between the case criteria models used to evaluate and treat. CCC, ICC, and IOM are all biomedical models, while the official version of NICE remained a biopsychosocial model. The pre-2021 NICE Guidelines inferred that the patient's condition resulted from mere deconditioning, dysfunctional cognition, and false ideas about pain and function that could be remedied with graded exercise therapy (GET) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Following extensive review and stakeholder input, NICE Guidelines were revised to more accurately reflect current scientific knowledge of the disease due to the recognition by NICE that “...assessment and treatment recommendations were not meeting the needs of people with ME/CFS” [in the UK], that recent reports from America on ME/CFS were potentially influencing the diagnostic criteria used by NICE, and lastly, that the PACE Trial, on which much of the current treatment recommendations [in the UK] are being appropriately questioned as scientifically inaccurate.[39] (See “Graded Exercise Controversy” at end of the page.) On 29 October 2021, the revised NICE Guidelines were released with clear statements from the authoring committee: "...that people with ME/CFS should not undertake a physical activity or exercise programme unless it is overseen by a physiotherapist who has training and expertise in ME/CFS and that using fixed incremental increases in physical activity or exercise (for example, graded exercise therapy), or physical activity or exercise programmes that are based on deconditioning and exercise avoidance theories, should not be offered to people with ME/CFS. The committee also wanted to reinforce that there is no therapy based on physical activity or exercise that is effective as a cure for ME/CFS."[37] They also advocated that the only use of cognitive behavioral therapy methods with this patient population should be to improve wellbeing and quality of life by decreasing the distress associated with having a chronic illness and lastly, avoidance of "The Lightning Process".[37]

Below are the diagnostic criteria for the earlier developed three biomedical case criteria models:

PEM can be objectively measured through a two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) in which the test subject with ME/CFS-derived PEM created by the first day’s test is unable to reproduce the maximal or anaerobic threshold measurements on the second day’s test.[41] The CPET is standardized for identifying malingering or lack of effort based on decades of normalized data. The results often serve as support for disability claims for ME/CFS patients. Due to the nature of the test, some patients experience a severe exacerbation of symptoms and the nature of the test does not allow testing of non-ambulatory/severe patients.[42]

*IOM’s collaborative selection of the name SEID, or systemic exercise intolerance disease, albeit a step above “chronic fatigue syndrome” was never embraced by the patient, clinician, or research communities and in 2017, the Center for Disease Control changed their website’s page on “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome or ME/CFS[43], which is the more commonly used term in the US for the disease. In 2021, with the adoption of the new NICE Guidelines, NHS followed suite with the adoption of this moniker.[37]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

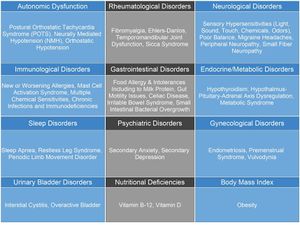

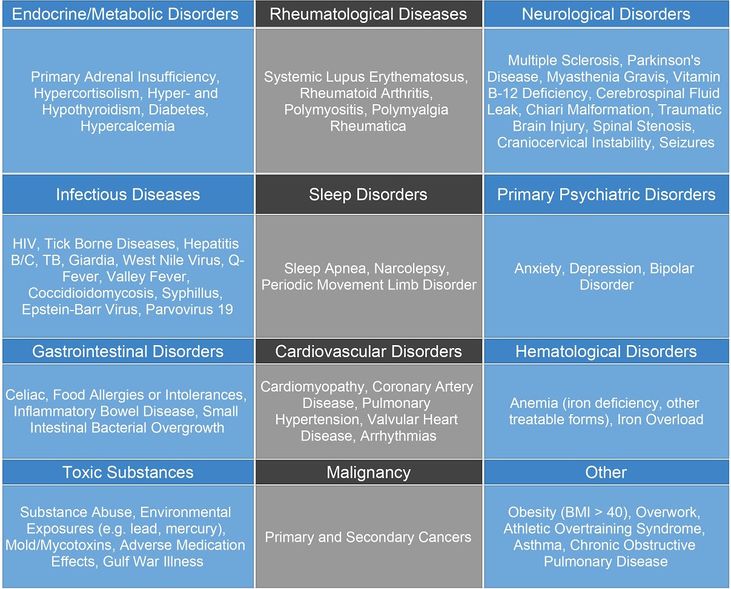

This chart shows the differential diagnosis of ME/CFS. It is important to note that many of these diagnoses may also be considered comorbidities of ME/CFS.

Common Comorbidities[edit | edit source]

This chart shows conditions often found occurring comorbidly with ME/CFS.

The overlap for the following conditions with ME/CFS have been identified in studies and are as follows:

- Fibromyalgia 20%-70% overlap[45]

- Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos 20% overlap[46]

- Migraine 60%-84% overlap[47]

- Orthostatic Intolerance 50%-97% overlap[48]

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome 25% overlap[49]

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome 35-90% overlap[50]

- Interstitial Cystitis 17% overlap[51]

- Endometriosis 36.1% overlap[52]

- Multiple Chemical Sensitivity 50% overlap[53]

- Chronic Pelvic Pain 33% overlap[54]

- Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction 33% overlap[54]

- Dysautonomia ~ 90% overlap[55]

- Chronic Low Back Pain 48% overlap[56]

- Post Concussion Syndrome 8% overlap[56]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Establishing a clear prognostic course for ME/CFS patients is difficult and highly variable due to the differences in the spectral nature of the illness and the varied presentations of the illness in each patient.

A 2005 systematic review showed that only a median estimate of 5% of ME/CFS patients returned to pre-illness function levels and of the remaining patients, most continued to be significantly impaired although up to approximately 40% of those did achieve some level of “substantial improvement” [which was not defined]. In the pediatric population, the prognosis is considered to be better than in the adult population[57], but it is rare for an adolescent affected by the disease to become completely symptom-free.[58]

The suicide rate in the ME/CFS population is difficult to study as there are many compounding factors, but a 2018 study of ME/CFS patients with suicidal ideation without depression found issues about resource acquisition, lack of empathetic social interactions, systemic healthcare challenges related to ME/CFS, loss of identity due to illness, and illness-induced distress, among other things, as the primary causes of the ideation.[59]

A 2017 survey conducted by Action for ME, a UK advocacy organization, found that of the 270 family respondents, 90% were concerned that their child's healthcare provider(s) did not believe them regarding their child's health complaints, 1:5 said a child protection referral had been made against them with nearly half of these referrals claiming "fabricated illness" (FI), formerly known as Munchausen's by Proxy, 17% of the claims were for child neglect with the remaining 10% and 2% for emotional and physical abuse, respectively. The FI statistical prevalence with this group far exceeds the national average in the UK and within a year of the initial complaint, 70% of all charges against parents of these children were dropped.[60] For children who are improperly cast into this system, the consequences can be dire. In addition to the psychological trauma of being taken from one's parents and in some cases institutionalized, the unwillingness of healthcare providers to recognize ME/CFS as the culprit instead of psychological issues or even character flaws of laziness and using methods of treatment counter to the standard of care - such as requiring the child to participate in graded exercise therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for treating dysfunctional illness beliefs for ME/CFS can leave lasting damage.[61]

ME/CFS has also been shown to be associated with an increased risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma possibly due to chronic immune activation.[62]

Deaths due to the biological course of the illness itself are rare but are likely underreported due to the complexity of issues surrounding case definitions of ME/CFS diagnosis, comorbid disease overlap, and resistance to acknowledging the disease in the medical community.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The most important thing medical clinicians need to do when working with ME/CFS patients is to validate the patient’s experience and the biological reality of this often misunderstood and frequently marginalized disease.

The patient, their family, potentially their employer, and/or school need to hear that this is a serious neurological illness and that the patient’s symptoms are not due to laziness, depression, or malingering.

The clinician should strive to work with ME/CFS-educated referral partners when referring the patient to others for collaborative care, but if this is not possible, should make every effort to share the most current and scientifically-based information on the illness with the other providers treating their patient.

The goal of medical management should be to support the patient’s function. Medical personnel should consider the impact of impaired function on work, school, home life, income, the continuance of health insurance, access to shelter, and food security. Providing access to patients with home health services including physical and occupational therapy, speech therapy (if indicated), nursing, and personal care attendants if available, disabled parking placards, authorization for durable medical devices such as rollators, electric wheelchairs, hospital beds, shower chairs, and bedside commodes can be transformative for these patients. Providing support for educational 504 plans for pediatric patients (in the USA) and Individual/Educational Health Care Plan(s)[63] (in the UK) and letters of support for work modification for adult patients, along with being willing to support disability applications with the appropriate documentation can be powerful tools of support to patients who have nothing in the way of treatment or curative options.

Next, medical management should be focused on informing the patient about pacing using heart rate, perceived exertion, and post-exertional symptoms as a guide. Due to the shortened periods of time physicians have with their patients, referring ME/CFS patients to ME/CFS knowledgeable physical or occupational therapists for appropriate training in these methods is not only appropriate but indicated for providing patients with non-drug interventions such as those mentioned above.

Currently, there are no drugs specifically for the treatment of ME/CFS. Medical management should be focused on using medications to minimize symptoms the patients experience such as pain, insomnia, migraines/headaches, etc. Additionally, medical management can focus on pharmaceutical control of symptoms caused by comorbid conditions. Effectively controlling these comorbid condition symptoms may, for some patients, make a considerable difference in their quality of life.[64]

The US ME/CFS Clinician Coalition has developed these outstanding resources for medical clinicians to guide testing and treatment for patients with ME/CFS. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Yu79EYxQIwNVER5tErp7LH7KY8pI8S_e/view[65] and https://drive.google.com/file/d/1T6psBJehr-6BuSNlCGfT6SKNbIFx0Lf5/view.[66]

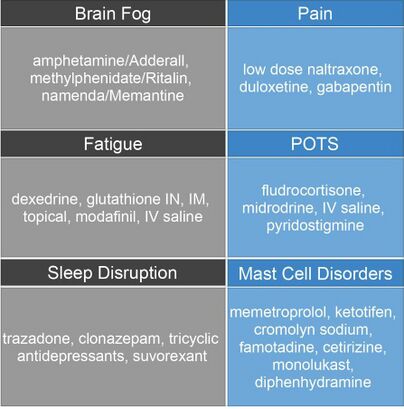

Pharmacological Management[edit | edit source]

These are drugs commonly used with ME/CFS patients. Many drugs used with ME/CFS patients are off-label uses as there are no drugs specifically for ME/CFS and the drugs used are simply for symptom management.

Physical Therapists should note that most of these drugs have negative side effects, including dizziness and shortness of breath.

Psychological Management[edit | edit source]

ME/CFS is not a psychological disorder.[69]

The primary way that providers will encounter psychological issues with ME/CFS patients is in the same way and frequency that they do with any other patient experiencing a chronic medical condition: occasional waves of loss, grief, and trauma resulting from all too common events of medical marginalization, and the stress of life in general. Compared to those with depression, those with ME/CFS report, on average, lower scores on the SF-36, different degrees of disability and pattern of impairment, different reporting of widespread pain, and show distinct brain physiology and difference in white matter volume.[70]It is a biological illness that is independent of primary depression.[71]

Patients with ME/CFS often describe periods of anxiety during their “crashes”. Again, this is not anxiety brought on by worry associated with life issues but it is frequently related to dysautonomia and waxes and wanes as dysautonomia symptoms flare and recede.[72]

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is not an appropriate treatment for ME/CFS in the context of reframing “inaccurate beliefs” and altering “activity avoidance.”[73] The CBT that is associated with successful chronic pain management programs is not effective nor an appropriate treatment approach in this patient population for the treatment of ME/CFS. They do not have faulty thinking or false ideas that have led to this pathology. Use of attention diversion strategies can be harmful due to drawing one's focus away from successful energy management. Cognitive retraining such as for "fear avoidance retraining" for kinesiophobia can be harmful as this may place the patient in a position to once again exceed the capabilities of their broken metabolic system and contribute erroneously to additional "patient blame" for their illness. Graded exposure to sensory challenges may likewise be sources of setbacks for these patients as specified doses of exposure to activity, sensory or cognitive demands all may exceed the patient's energy limitations at any given moment. The patient needs to be taught to listen carefully to their energy demands and to respond conservatively in order to have improved quality of life.

Physiological Findings and Physical Therapy[edit | edit source]

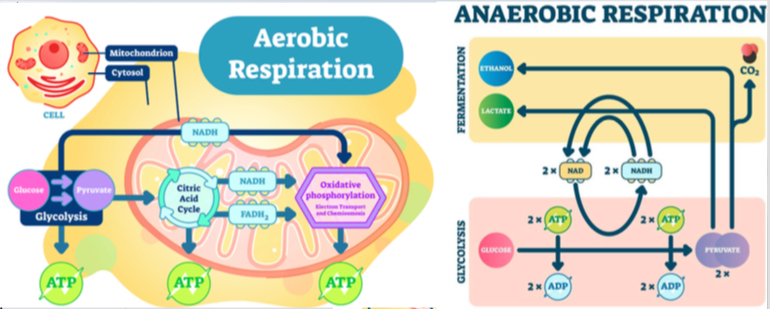

As most physical therapy treatments are ultimately focused on exercise and movement, physical therapists need to review the aerobic and anaerobic respiratory cycles as they relate to ME/CFS patients.

Physical therapists must recognize that research indicates the aerobic metabolism system in those with ME/CFS is broken and according to Dr. Mark Van Ness of the University of the Pacific, “Classic exercise training produces little improvement and may result in PEM”. He also states, “Aerobic conditioning does not appear to improve or repair broken aerobic metabolism.”[74]

''''Dialogues for ME/CFS'' is made possible with a reward from the Wellcome Public Engagement Fund. Click https://www.dialogues-mecfs.co.uk/ for access to additional scientifically-based videos on ME/CFS.'''

There are three main observations obtained from the CPET studies. First, patients with ME/CFS display low VO2 at anaerobic threshold and peak output. This means that there is impairment in the exchange of air in patients with ME/CFS. Secondly, patients with ME/CFS display an increased incidence of chronotropic intolerance. This means their heart rate does not increase as much as one would expect with the performance of an activity. This results in decreased blood to the brain and muscles. Lastly, there is a decreased ventilatory response in patients with ME/CFS. This results in less air exchange, poor oxygenation, respiratory muscle fatigue, chemosensitivity of the tissues, and CO2 retention leading to an acidotic state contributing to “the burn” felt in muscles that is perceived by ME/CFS patients (this burn is different than delayed onset muscle soreness).[74]

Additionally, there is increased awareness and discussion of the role of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) in the ME/CFS population as is noted by ME/CFS specialist Dr. Susan Levine, “I suspect 50% to 60% of ME/CFS patients have it…”[76] referring to a problematic condition in which a normal number of mast cells exist within the body, but release abnormal levels of histamine and histamine-like substances resulting in a myriad of body-wide signs and symptoms.[76] Physical therapists should be cognizant of the fact that mast cells are known to degranulate with the application of longitudinal stretch, releasing histamines, prostaglandins, etc. This may contribute to acute and/or delayed responses to stretch as PEM whether applied passively by the therapist or when actively performed by the patient.[77]

In work presented at the 2019 Emerge Conference in Australia[78] researcher Neil MacGregor presented ME/CFS as a “Hypermetabolic or hypercatabolic disease” similar to burns, trauma, sepsis, severe stress, and post-surgical conditions. As most therapists would know, 4-6 weeks recovery is adequate to see significant healing take place with the other listed hypermetabolic pathologies”, but MacGregor stated that, “ME/CFS gets stuck in a shifted metabolic state”. One of the consequences of this shifted state is increased connective tissue degradation. MacGregor goes on to describe the discovery by Dr. Ron Davis in his patient group of study who are the most severely affected patients with ME/CFS, of high levels of connective tissue metabolites suggesting increased connective tissue breakdown. Physical and occupational therapists need to be aware of this when contemplating any type of movement or manual therapy or in severe cases, transferring or instituting position changes with a patient. Therapists monitoring post-surgical incisions need to be acutely aware of the increased possibility of dehiscence of the surgical incision.

Physical Therapy Intervention[edit | edit source]

Every physical therapist should be familiar with ME/CFS as a diagnosis and know the basics of safely treating ME/CFS patients. There is no venue of practice that by its nature excludes those with ME/CFS. The four most important things for physical therapists to know about treating ME/CFS are:

1.) How to respond to and safely treat a patient who knows they have the diagnosis.

2.) How to appropriately refer a patient with ME/CFS who knows they have the diagnosis who is not an appropriate candidate for your particular venue of practice.

3.) How to recognize when the patient’s condition requires referral to a multi-disciplinary team including specialized physical therapy providers.

4.) How to recognize that a lack of improvement in a patient who is compliant with a therapeutic exercise program may be indicative, with specific subjective and objective complaints, of having an undiagnosed case of ME/CFS and require referral to an appropriate medical doctor and that continued exercise may be permanently harmful to your patient.

Just as autonomous practice/direct access has enabled widening the scope of PT practice in the US and beyond, it is the duty of PT’s to familiarize themselves with this disease and be able to differentially diagnose and treat appropriately, just as they would with any other serious neurological disease as independent healthcare providers. Treating this disease inappropriately or contrary to the scientific consensus is no different than neglectfully ignoring red or yellow flag signs with another illness.

Assessment and Treatment of ME/CFS patients:[edit | edit source]

- Validate your patient. Again, your patient has likely seen many providers who didn’t know what to do, misdiagnosed them, or outright marginalized their condition. Acknowledge that you know this a biological illness and that you understand it is complex and can greatly impact a person’s quality of life. _______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Perform a thorough evaluation but do so in a manner that respects the limitations created by the illness that are specific to the patient. Remember the illness is highly variable and occurs on a spectrum. You may see a mildly impacted or very severely impacted individual. The patient may be hyperacusic, misophonic, photophobic, olfactory triggered, temperature unstable, and adverse to touch. Be willing to speak quietly and modify lighting if needed. Avoid wearing clothing that has patterns or strong colors and maybe retaining odors such as cigarette smoke or fragrances. Allow the patient to lie down as much as possible. Provide a blanket if necessary. Take a thorough history and ask what types of physical therapy (or other interventions) they have had in the past. What worked? What didn’t? Assess how knowledgeable they are about ME/CFS so that you may tailor the time spent together effectively. (They may know much more than you which is not uncommon as these patients have had to be their own advocates for so long due to the dearth of knowledgeable providers. Use this knowledge to your advantage.) Establish what your patient’s goals are and in what order. Is function more important to them than pain control? Or are both equally important? You may need to divide the evaluation into multiple sessions. In the case of more severely impacted patients, you may be interacting almost solely with the care provider to gather such information. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Determine your patient’s energy limitations first, based on oral history, report of measures such as “hours upright” in which the patient logs hours of standing/walking/running, sitting with both feet planted, sitting with feet elevated, and fully reclined.[79] Patient log of activities and corresponding PEM is another way to obtain trackable information about the patient’s functional activities. Have the patient include in the activity log non-physical activities such as screen-time, social interactions, cognitive and emotional stressors, and any corresponding post-exertional malaise (PEM) that may result. All treatment, regardless of the purpose, will be constrained by the patient’s energy limitations. Have your patient complete the Depaul Symptom Questionnaire Short Form for PEM.[80] _____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Introduce the patient or care provider to the concept of “ heart rate biofeedback pacing” ideally using a heart rate monitor, including determining what an estimated heart rate at anaerobic threshold should be if an objectively determined anaerobic threshold is unavailable. Have the patient collect “awakening” resting heart rates (not necessarily morning as they may have flipped sleep schedules) for, it is recommended to ultimately establish estimated ventilatory anaerobic threshold using Workwell Foundation's recommended resting heart rate plus 15 beats per minute calculation for ME/CFS patients. Use Heart Rate Monitor Factsheet from Workwell to guide the process.[81] To effectively begin heart rate pacing at the first appointment while patients collect resting heart rate data, it can be useful to have them "start conservatively with 100 beats per minute."[81] ______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Use PEM Timecourse[82] from the Workwell Foundation to teach about post-exertional malaise symptoms including cognitive and emotional activities/stressors. For cognitive and emotional stressors that may not result in elevated HR, maintaining a log of possible triggers and PEM symptoms may help patients learn to pace these types of events. For patients reliant on care providers, instruct the care providers in the PEM Timecourse document for the pacing of care activities, etc. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Use the Borg Rate of Perceived Exertion Scale[83] to establish the perceived effort of the activity with the patient. All activities should be very light or light. The patient should not be short of breath. Shortness of breath may present in various forms of altered breathing patterns such as sighing, alteration in speed, or depth. Be observant to help your patient learn these subtle clues to PEM warning. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Teach patient or care provider energy conservation skills specific to their living and work circumstances; consider the impact of sensory processing and include this as part of energy conservation strategies. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Utilize Durable Medical Equipment (DME) or other tools for energy conservation including fitting the patient for an electric wheelchair, transporter chair, standard wheelchair, lifts, and other assistive devices. The patient may benefit from using reachers, shower chairs, bedside commodes, and ergonomic equipment for computer use, kitchen tasks, work, etc. Measure and fit the patient for Over the counter (OTC) or custom compression stockings, if indicated. Teach patient and/or care provider to don and doff with energy conservation in mind. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Use the above collected data (anaerobic threshold, PEM symptoms, DSQ-PEM short form, RPE of very light or light) and energy conservation methods to guide all intervention (interpersonal interaction, eval, assessment, and treatment) to prevent cyclical push/crash cycles pf PEM or persistent crash/PEM status of the ME/CFS patient. To deal with possible flare ups of ME/CFS symptoms including PEM, the patient and PT need to analyze possible triggers and temporarily reduce all activities and add more resting periods to the daily schedule until the flare-up subsides. Utmost care is to be taken to not let flare-ups turn into relapse.[33] In case of relapse, carefully reassess the patient for energy limitations using previously described tools. Immediately remodel the line of treatment by completely halting all but the most basic ADLs. Be mindful that a patient could take months to recover from a relapse.[33]As the patient recovers, reassess them and establish goals for further maximal independence within limits of PEM. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Instruct patient (that can tolerate instruction) in the use of diaphragmatic and pursed-lip breathing for promotion of parasympathetic activation, improved alveolar expansion, and respiratory efficiency. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Measure and fit patient for OTC or custom-made splints for unstable joints related to comorbid hEDS/HJS. Teach patient/care provider to don and doff with energy conservation in mind. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Instruct patient/care provider in options for positioning to optimize skin integrity, decrease soft tissue strain, and improve ergonomics. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Utilize pain management modalities as indicated. The use of modalities must be judiciously applied and assessed conservatively for any PEM or other negative impacts on function or QoL. Test with brief trials and progress only if tolerated and remember PEM, indicating intolerance to the treatment, may occur hours to days later. Gentle forms of soft tissue manipulation such as myofascial release, craniosacral therapy, and lymphatic drainage are reported anecdotally as being more tolerated than more vigorous forms of soft tissue manipulation[84] [85]such as petrissage/effleurage, deep tissue manipulation. Passive range of motion is considered a method to “bridge the gap to exercise.” [77]______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Exercises should be initiated only after the patient can complete all ADLs/IADLs without setbacks due to PEM that result in eliminating ADLs/IADLs or other meaningful routine activities from their agenda. The focus should be on large muscle activation with short-duration loading of fewer than 2 minutes to stay within the anaerobic respiration cycle. Close attention to HR, perceived symptoms, and PEM should be paid throughout the exercise.[86]As the ME/CFS patient population lacks disease homogeneity, exercise should be detailed specifically to the unique responses of the individual patient with adequate time in between to fully assess PEM response with at minimum 1:3 rest cycle. All exercises should be focused on optimizing specific functional tasks. Generalized fitness goals for bone density, cardiopulmonary health, muscle strength, etc. is to be integrated into exercise/movement programs within the limitations of PEM as described previously. NOTE: there are patients for whom "exercise" will always be off-limits. Skilled therapists recognize the heterogeneity of the ME/CFS population and DO NOT apply broad goals to those with this diagnosis. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- THERE IS NO NEED TO “WARM-UP” THESE PATIENTS! Their energy available for activity is so severely limited, the “warm-up” would for the average ME/CFS patient, use all available energy and likely trigger PEM. Similarly, avoid physical performance measures such "6-Minute Walk" as this is not a useful measure in this population and simply uses severely limited energy inappropriately and unnecessarily.[87] _______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Consider referral to specialized physical therapy for any issues related to comorbid conditions that may be adding to symptomatology and negatively impacting functionality and QoL that may be beyond the scope of your services as a physical therapy provider. Refer to physical therapists willing to practice “safe ME/CFS” treatment only. _______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Determining the frequency of appointments should be based on the energy cost to therapeutic benefit ratio for the patient. If the patient is to be seen in the clinic, consider the effects of preparation and travel time to get to the appointment. In addition, work with the patient to accommodate the disrupted sleep patterns of the patient by working to have them on a set schedule during a time that is easiest for them to be successful with attendance and their physical therapy program. Avoid scheduling during their most difficult periods of function. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Scheduling for home health patients must factor in ADLs and other home health services as the patient will be impacted by these other tasks and interventions. Work to schedule during times that optimize the patient’s ability to succeed and participate in physical therapy. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Goals should be written to capture the small gains achievable by ME/CFS patients so that they may receive the services that they need. Goal achievement will be slow and require small measurements to achieve. Goals should be functional in nature. Keep in close contact with other healthcare team members regarding any change in status such as unintended weight loss, difficulty eating/retaining food, increased evidence of emotional stress pertaining to healthcare access, support or lack thereof, access to food, safe housing with the continuance of utilities, and legal resources. REMEMBER, THE GOAL IS TO OPTIMIZE FUNCTION FOR THESE PATIENTS WITHIN THEIR ENERGY LIMITATIONS AND AVOID TRIGGERING POST-EXERTIONAL MALAISE.

Graded Exercise Therapy Controversy[edit | edit source]

The PACE TRIAL[88]

In 2005, patient recruitment began for the PACE Trial - Pacing, Graded Activity, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and randomized Evaluation, which was conducted in the UK under the auspices of the UK Medical Research Council, Depart of Health and Social Care (UK) for England, Scottish Chief Scientist Office, and Department for Work and Pensions. The investigators were Peter White, a psychiatrist, Trudie Chalder, a professor of cognitive behavioral therapy, and Michael Sharpe, a professor of psychological medicine.

This study, which is the most well-funded single piece of ME/CFS research ever conducted, was designed to compare three different approaches to treatment:

1) Specialist Medical Care (SMC), which included the use of medications for symptoms management and instruction in avoidance of extreme activity or inactivity to SMC plus Adaptive Pacing Therapy (APT), which is activity engagement limited by symptoms of PEM on one extreme and complete inactivity on the other;

2) Informing the group that they were not ill, but rather deconditioned and should gradually return to activities and that there was nothing preventing their recovery; and

3) CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) and GET (Graded Exercise Therapy) with the premise that deconditioning, dysfunctional cognition, and false ideas were the source of their symptoms and functional limitations. The GET was to be advanced in a structured manner with the ultimate goal of the patients participating in regular aerobic exercise.

The PACE Trial outcomes were reported in The Lancet in 2011. The study stated that based on patient self-report the CBT/GET group out-performed the APT and SMC groups. Immediately there was controversy as the authors overstated the outcomes and made proclamations about the outcomes in public discussions of the study. The subject outcry was immediate and swift regarding their perceived differences with the study findings. In 2013, the authors went further and published another article stating that the CBT/GET group out-performed the ABT and SMC groups 22% to 8% and 7%, respectively.

There were several very concerning methodological issues with this study. Briefly, they were:

- PACE Trial used overly broad case criteria to select ME/CFS patients. This resulted in a disproportionately high number of mildly affected individuals in the study, including individuals that did not necessarily meet the criteria for ME/CFS diagnosis, but did meet the criteria for a diagnosis of depression which responds distinctly differently to exercise than ME/CFS.

- The researchers changed the criteria for outcome efficiency and recovery mid-trial. Despite years of requests directed to the researchers for the data based on the original outcome target and recovery definition, they have consistently refused.

- The main outcome measures were subjective. Patients were actively told in the CBT/GET group, but not in others, “if you do this, there is nothing to stop you from recovering”.

- The research authors did not disclose to the participants a potential conflict of interest.

- The researchers published and provided a newsletter to the trial participants while the study was ongoing. There was material in at least one of the newsletters that could have influenced the views of the participants.

The consequences of the PACE Trial were:

- Because of its size, the PACE Trial dominates evidence-based research on ME/CFS, regardless of its quality or lack of it.

- Especially in the UK, it has been very influential in establishing standards of care for ME/CFS patients.

- Cochrane Review was heavily weighted in its findings because of the size of this poorly conducted study.

- Researchers base their work on the “evidence” reported through Cochrane and this results in the unintended continuation of poor science.

- Researchers, ME/CFS advocates, and patients have spent thousands of hours of valuable time and money trying to gain access to the raw data to re-examine PACE, to have it rescinded by The Lancet, and to have the original researchers admit to their erroneous and harmful work.

In March 2018, BMC Psychology published 'Rethinking the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome—A reanalysis and evaluation of findings from a recent major trial of graded exercise and CBT' by Drs Carolyn Wilshire, David Tuller, Tom Kindlon, Alem Matthees, Keith Geraghty, Robert Courtney, Bruce Levin, and posthumously Robert Courtney. This reexamination concluded there should not only be serious concerns about the PACE trial but also the strength of the claims made about the efficacy of CBT and GET as a whole for ME/CFS treatment. The reanalysis is published with full access on PubMed.[89]

Failure of physical therapists and especially academicians in the physical therapy world who are not familiar with the background of this scientific scandal are likely to pass along to their students and peers inaccurate information put forth by this harmful document which will not only continue to result in ineffective care for patients with ME/CFS, but potentially harming them and worsening their conditions, and reinforcing the inaccurate notion that physical therapy has nothing useful to provide ME/CFS patients.

Long COVID/ Long Haulers[edit | edit source]

Following the outbreak of COVID-19 in late 2019 in Wuhan Province, China, and its rapid spread into other parts of the world, researchers, scientists, and patients familiar with post-viral syndromes began to become concerned not only about the acute danger of this particular virus but the potential long-term sequelae. Following SARS-1, West Nile Virus, H1N1 influenza virus[90], and other reports claim, “that up to 11% of patients who had severe infections from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Q fever (Coxiella burnetii), or Ross River virus (RRV), and others, develop ME/CFS. Other studies following SARS and MERS suggest an even higher proportion (50%) develop ME/CFS or Fibromyalgia."[91]

Given that some estimates suggest as much as 75% of all ME/CFS patients developed their illness following a post-viral or post-bacterial illness[92], there has been considerable frustration in the ME/CFS community-researchers and patients alike-that had ME/CFS patients been taken more seriously all along, then research into what causes this debilitating outcome in some patients and not in others would have been identified and potentially remedied by now.

Additionally, there is great frustration in the ME/CFS community as they watch these new cases as they are now being officially diagnosed as they pass the six-month mark required for official ME/CFS diagnosis.

The great majority of ME/CFS sufferers recognized the potential for this post-viral sequelae long before the first public comments were made by public health officials and patient advocacy groups were sounding the alarms.

ME/CFS patients have felt frustration and anger that had research been done adequately on ME/CFS throughout the years, this new population of post-viral fatigue sufferers would not be going down the same familiar road: being treated as malingerers, hypochondriac and/or mental health cases.

Many long COVID patients report being diagnosed with anxiety.[93] Furthermore, watching these long haulers try to rehabilitate using a conventional rehabilitation model is “like watching a car wreck going to happen and you can’t stop it.”[94]

The lessons learned with post-viral fatigue care through the ME/CFS population is unfortunately not being carried over into the long COVID community in the great majority of cases despite statements by leading PT/physiotherapist organizations such as global World Physiotherapy. Whereas, World Physiotherapy advocates in their second briefing paper on post-intensive care rehabilitation for Covid-19 patients, have asked to follow the model for post-viral illnesses, like ME/CFS which includes focusing on rest, hydration, and nutrition, in the event where symptoms stay persist into the 5-6 month period, also ME/CFS diagnosis should be considered and physical therapy intervention should proceed as indicated above with a focus on the unique symptoms experienced by the patient, monitoring of PEM, perceived effort, and HR relative to estimated anaerobic threshold.[95][96]

Resources[edit | edit source]

https://www.facebook.com/groups/3049027761780369/ Peer-to-peer education group for PTs and OTs led by administrators who are PTs /OTs living with ME/CFS.

https://www.physiosforme.com/ Physiotherapy special interest group for ME/CFS. Provides information for therapists and patients.

https://workwellfoundation.org/ The leader in exercise-based research into ME/CFS.

https://www.meaction.net/ International ME/CFS advocacy group with a wide range of patient and provider resources.

https://solvecfs.org/ Non-profit committed to aggressively expanding funding for the development of safe and effective treatments for ME/CFS.

https://mecfscliniciancoalition.org/ Concise and well-organized website specifically for medical providers to assist in diagnosis and treatment of ME/CFS.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) [Internet]. Cdc.gov. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/index.html

- ↑ About the disease [Internet]. Solvecfs.org. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 3]. Available from: https://solvecfs.org/about-the-disease/

- ↑ Maes M, Anderson G, Morris G, Berk M. Diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis: where are we now? Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2013;7(3):221–5.

- ↑ U.S. me/CFS clinician coalition [Internet]. Mecfscliniciancoalition.org. 2020d [cited 2021 Feb 1]. Available from: https://mecfscliniciancoalition.org/

- ↑ Battery B. What is ME? [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKPdgz612nU

- ↑ About the disease [Internet]. Solvecfs.org. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 3]. Available from: https://solvecfs.org/about-the-disease/

- ↑ Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Review of the evidence on major ME/CFS symptoms and manifestations. Washington, D.C., DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

- ↑ Adhopia V. After long-awaited recognition, serious research begins on chronic fatigue syndrome. CBC News [Internet]. 2019 Oct 23 [cited 2020 Sep 4]; Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/chronic-fatigue-recognition-research-1.5330712

- ↑ What is ME/CFS? [Internet]. Org.au. [cited 2020 Sep 4]. Available from: https://www.emerge.org.au/what-is-mecfs

- ↑ Rachael Maree Hunter, Jon Paxman, Matt James. Counting the Cost Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis [Internet]. 2017 Sep. Available from: https://meassociation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020Health-Counting-the-Cost-Sept-2017.pdf

- ↑ Falk Hvidberg M, Brinth LS, Olesen AV, Petersen KD, Ehlers L. The health-related quality of life for patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132421.

- ↑ What is ME? - #MEAction network [Internet]. Meaction.net. 2020g [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.meaction.net/learn/what-is-me/

- ↑ Battery B. What is ME? [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKPdgz612nU

- ↑ Wichita clinical study [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020m Oct 24]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Wichita_Clinical_Study

- ↑ About the disease [Internet]. Solvecfs.org. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 3]. Available from: https://solvecfs.org/about-the-disease/

- ↑ Dialogues for a neglected illness [Internet]. Dialogues-mecfs.co.uk. 2017 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.dialogues-mecfs.co.uk/

- ↑ Rowe PC, Underhill RA, Friedman KJ, Gurwitt A, Medow MS, Schwartz MS, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome diagnosis and management in young people: A primer. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:121.

- ↑ Jason LA, Katz BZ, Sunnquist M, Torres C, Cotler J, Bhatia S. The prevalence of pediatric myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in a community-based sample. Child Youth Care Forum. 2020;49(4):563–79. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09543-3

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Introduction. Washington, D.C., DC: National Academies Press; 2015a.

- ↑ Solvecfs.org. [cited 2021v Feb 24]. Available from: https://solvecfs.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Jason-Mirin_Prevalence_econ_update.pdf

- ↑ Davenport TE, Stevens SR, VanNess MJ, Snell CR, Little T. Conceptual model for physical therapist management of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Phys Ther. 2010;90(4):602–14.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. Chronic fatigue syndrome [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chronic_fatigue_syndrome&oldid=980257034

- ↑ Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Review of the evidence on major ME/CFS symptoms and manifestations. Washington, D.C., DC: National Academies Press; 2015b.

- ↑ Paediatric ME/CFS [Internet]. Voicesfromtheshadowsfilm.co.uk. [cited 2020g Oct 12]. Available from: https://voicesfromtheshadowsfilm.co.uk/paediatric-mecfs/

- ↑ Nacul DL. Post-Exertional Malaise [Internet]. Dialogues. 2020 [cited 2021Feb5]. Available from: https://www.dialogues-mecfs.co.uk/films/post-exertional-malaise/

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 26.7 Causes [Internet]. Phoenixrising.me. 2011 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://phoenixrising.me/mecfs-basics/the-causes-of-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-mecfs-2

- ↑ Walsh N. Rituximab Fails in Chronic Fatigue [Internet]. MedpageToday. 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.medpagetoday.com/rheumatology/generalrheumatology/78944

- ↑ Proskauer C. Antiviral treatment creates improvement in a subset of ME/CFS patients [Internet]. Massmecfs.org. [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.massmecfs.org/research/recent-research/5-cfscfidsme/247-antiviral-treatment-creates-improvement-in-a-subset-of-cfscfidsme-patients

- ↑ Morris G, Anderson G, Maes M. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal hypofunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)/chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) as a consequence of activated immune-inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative pathways. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(9):6806–19.

- ↑ Causes [Internet]. Phoenixrising.me. 2011 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://phoenixrising.me/mecfs-basics/the-causes-of-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-mecfs-2

- ↑ Dibble JJ, McGrath SJ, Ponting CP. Genetic risk factors of ME/CFS: A critical review. Hum Mol Genet [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 29]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/hmg/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hmg/ddaa169/5879704

- ↑ Meaction.net. [cited 2020n Oct 2]. Available from: https://www.meaction.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/19_MEA_Revised_2019_Research_Summary_190610.pdf

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: Diagnosis and management: Guidance. NICE guideline [NG188]. 2020 . Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/chapter/recommendations#care-and-support-plan

- ↑ Fukuda criteria [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020e Nov 15]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Fukuda_criteria

- ↑ Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, Mitchell T, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International consensus criteria: Review: ME: Intl. Consensus Criteria. J Intern Med. 2011;270(4):327–38.

- ↑ Canadian Consensus Criteria [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020a Sep 29]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Canadian_Consensus_Criteria

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 NICE clinical guideline [Internet]. Org.uk. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 9]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/resources/myalgic-encephalomyelitis-or-encephalopathychronic-fatigue-syndrome-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66143718094021

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Review of the evidence on major ME/CFS symptoms and manifestations. Washington, D.C., DC: National Academies Press; 2015b.

- ↑ NICE clinical guideline [Internet]. Org.uk. 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://meassociation.org.uk/about-what-is-mecfs/nice-clinical-guideline/

- ↑ US ME/CFS Clinician Coalition. Diagnosing And Treating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SG7hlJTCSDrDHqvioPMq-cX-rgRKXjfk/

- ↑ Dr. Mark Van Ness, “expanding physical capability in ME/CFS” part 1 (of 2) - YouTube [Internet]. Youtube.com. Youtube; [cited 2020d Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/embed/FXN6f53ba6k

- ↑ Dialogues for a neglected illness [Internet]. Dialogues-mecfs.co.uk. 2017 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.dialogues-mecfs.co.uk/

- ↑ Chronic fatigue syndrome [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020b Sep 29]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Chronic_fatigue_syndrome

- ↑ US ME/CFS Clinician Coalition. Diagnosing And Treating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SG7hlJTCSDrDHqvioPMq-cX-rgRKXjfk/

- ↑ Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Review of the evidence on major ME/CFS symptoms and manifestations. Washington, D.C., DC: National Academies Press; 2015b.

- ↑ Comorbidities of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020c Sep 30]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Comorbidities_of_Myalgic_Encephalomyelitis

- ↑ Overlapping Conditions [Internet]. Ammes.org. [cited 2020d Sep 30]. Available from: https://ammes.org/overlapping-conditions/

- ↑ Comorbidities of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020c Sep 30]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Comorbidities_of_Myalgic_Encephalomyelitis

- ↑ van Campen CLMC, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Low sensitivity of abbreviated tilt table testing for diagnosing postural tachycardia syndrome in adults with ME/CFS. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:349.

- ↑ RachelBlack. New research on tentative ME/CFS irritable bowel syndrome subgroup [Internet]. Batemanhornecenter.org. [cited 2020 Sep 30]. Available from: https://batemanhornecenter.org/mecfs_possibleibssubgroup/

- ↑ Aaron LA, Herrell R, Ashton S, Belcourt M, Schmaling K, Goldberg J, et al. Comorbid clinical conditions in chronic fatigue: a co-twin control study. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):24–31.

- ↑ Boneva RS, Lin J-MS, Wieser F, Nater UM, Ditzen B, Taylor RN, et al. Endometriosis as a comorbid condition in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): Secondary analysis of data from a CFS case-control study. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:195.

- ↑ Overlapping Conditions [Internet]. Ammes.org. [cited 2020d Sep 30]. Available from: https://ammes.org/overlapping-conditions/

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Aaron LA, Herrell R, Ashton S, Belcourt M, Schmaling K, Goldberg J, et al. Comorbid clinical conditions in chronic fatigue: a co-twin control study. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):24–31.

- ↑ Robinson LJ, Durham J, MacLachlan LL, Newton JL. Autonomic function in chronic fatigue syndrome with and without painful temporomandibular disorder. Fatigue. 2015;3(4):205–19.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Aaron LA, Herrell R, Ashton S, Belcourt M, Schmaling K, Goldberg J, et al. Comorbid clinical conditions in chronic fatigue: a co-twin control study. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):24–31.

- ↑ Prognosis for myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020e Sep 30]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Prognosis_for_myalgic_encephalomyelitis_and_chronic_fatigue_syndrome

- ↑ Omf.ngo. [cited 2020i Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.omf.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ME-in-Children.pdf

- ↑ Suicide [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020g Sep 30]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Suicide

- ↑ https://www.actionforme.org.uk/uploads/pdfs/families-facing-false-accusations-survey-results.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2FjNtY63YfRvLaRPwFIgoqubXAq-2otOp8r8IDguf4GDKwqRB900unBls

- ↑ https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/8/3/211

- ↑ Chang CM, Warren JL, Engels EA. Chronic fatigue syndrome and subsequent risk of cancer among elderly US adults. Cancer. 2012;118(23):5929–36.

- ↑ https://www.actionforme.org.uk/uploads/pdfs/Education-support-for-pupils-with-ME-July-2021.pdf

- ↑ Paediatric ME/CFS [Internet]. Voicesfromtheshadowsfilm.co.uk. [cited 2020g Oct 12]. Available from: https://voicesfromtheshadowsfilm.co.uk/paediatric-mecfs/

- ↑ Clinical management - U.s. me/CFS clinician coalition [Internet]. Mecfscliniciancoalition.org. 2020c [cited 2021 Apr 15]. Available from: https://mecfscliniciancoalition.org/clinical-management/ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Yu79EYxQIwNVER5tErp7LH7KY8pI8S_e/view

- ↑ Clinical management - U.s. me/CFS clinician coalition [Internet]. Mecfscliniciancoalition.org. 2020c [cited 2021 Apr 15]. Available from: https://mecfscliniciancoalition.org/clinical-management/ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1T6psBJehr-6BuSNlCGfT6SKNbIFx0Lf5/view

- ↑ US ME/CFS Clinician Coalition. Diagnosing And Treating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SG7hlJTCSDrDHqvioPMq-cX-rgRKXjfk/

- ↑ Log into Facebook [Internet]. Facebook.com. [cited 2020d Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/groups/3049027761780369/learning_content/?filter=1492747254239771&post=2580818908622680

- ↑ Frcp(c ESMD. Assessment and treatment of patients with ME/CFS: Clinical guidelines for psychiatrists [Internet]. Asn.au. [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://sacfs.asn.au/download/guidelines_psychiatrists.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2GqvvZKy3AYrf08ggek3SiY4h8tp-z0hyyqYULYSOUXw2ooD0QuZGtV6o

- ↑ McManimen SL, Devendorf AR, Brown AA, Moore BC, Moore JH, Jason LA. Mortality in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. Fatigue. 2016;4(4):195–207.

- ↑ Frcp(c ESMD. Assessment and treatment of patients with ME/CFS: Clinical guidelines for psychiatrists [Internet]. Asn.au. [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://sacfs.asn.au/download/guidelines_psychiatrists.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2GqvvZKy3AYrf08ggek3SiY4h8tp-z0hyyqYULYSOUXw2ooD0QuZGtV6o

- ↑ Amjmed.com. [cited 2020p Oct 17]. Available from: https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(04)00105-6/fulltext

- ↑ Wilshire CE, Kindlon T, Courtney R, Matthees A, Tuller D, Geraghty K, et al. Rethinking the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome—a reanalysis and evaluation of findings from a recent major trial of graded exercise and CBT. BMC Psychol [Internet]. 2018;6(1). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0218-3

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Dr. Mark Van Ness, “expanding physical capability in ME/CFS” part 1 (of 2) - YouTube [Internet]. Youtube.com. Youtube; [cited 2020d Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/embed/FXN6f53ba6k

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Stevens S, Snell C, VanNess M, Hughes B, Edwards J. Graded Exercise Therapy [Internet]. Dialogues. 2021 [cited 2021Feb5]. Available from: https://www.dialogues-mecfs.co.uk/films/graded-exercise-therapy/

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Mast cell activation syndrome [Internet]. Mast cell activation syndrome - MEpedia. [cited 2021Jan29]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Mast_cell_activation_syndrome

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Rowe PC, Fontaine KR, Lauver M, Jasion SE, Marden CL, Moni M, et al. Neuromuscular strain increases symptom intensity in chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159386.

- ↑ An omic analysis of ME/CFS – an assessment of potential mechanisms [Internet]. Org.au. 2019a [cited 2020 Nov 21]. Available from: https://mecfsconference.org.au/videos/neil-mcgregor/

- ↑ Bateman Horne Center. Postural Biomarkers as Outcome Measures for ME/CFS [Internet]. Youtube; 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oTfOie4rVvw

- ↑ https://leonardjason.files.wordpress.com/2021/06/dsq-short-form-pem-questionnaire.pdf?fbclid=IwAR0skhT5nZcv1qWVnmYxsJ4g7int2t-_cgCWCT0w0klU7zFDJcjcjgjd2pQ

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Accredited online courses [Internet]. Workwellfoundation.org. 2020a [cited 2021 Feb 1]. Available from: https://workwellfoundation.org/educational-videos/

- ↑ Workwellfoundation.org. [cited 2020r Oct 18]. Available from: https://workwellfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WW-PEM-Timecourse.pdf

- ↑ Perceived Exertion (Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale) [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020 [cited 2021Jan29]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/exertion.htm

- ↑ Facebook groups

- ↑ Paediatric ME/CFS [Internet]. Voicesfromtheshadowsfilm.co.uk. [cited 2020g Oct 12]. Available from: https://voicesfromtheshadowsfilm.co.uk/paediatric-mecfs/

- ↑ Dr. Mark Van Ness, “expanding physical capability in ME/CFS” part 1 (of 2) - YouTube [Internet]. Youtube.com. Youtube; [cited 2020d Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/embed/FXN6f53ba6k

- ↑ https://meassociation.org.uk/product/long-covid-me-cfs/

- ↑ PACE trial [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020h Sep 30]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/PACE_trial

- ↑ PACE trial [Internet]. Me-pedia.org. [cited 2020f Sep 30]. Available from: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/PACE_trial

- ↑ Tuller D, Lubet S, McCoy MS, Libert T, Friedman AB, Bendicksen L, et al. Post-Covid syndrome prompts new look at chronic fatigue syndrome- STAT [Internet]. Statnews.com. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.statnews.com/2020/07/21/chronic-fatigue-syndrome-keys-understanding-post-covid-syndrome/

- ↑ Breaking news – OMF funded study: COVID-19 and ME / CFS 5/19/29 [Internet]. Omf.ngo. 2020a [cited 2020 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.omf.ngo/2020/05/19/omf-funded-study-covid-19-and-

- ↑ Researchers warn covid-19 could cause debilitating long-term illness in some patients. Washington post (Washington, DC: 1974) [Internet]. 2020c May 29 [cited 2020 Sep 30]; Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/could-covid-19-cause-long-term-chronic-fatigue-and-illness-in-some-patients/2020/05/29/bcd5edb2-a02c-11ea-b5c9-570a91917d8d_story.html

- ↑ Mervosh S. ‘it’s not in my head’: They survived the Coronavirus, but they never got well. The New York times [Internet]. 2020 Sep 28 [cited 2020 Sep 30]; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/28/us/coronavirus-long-term-effects.html

- ↑ PT/OT 4 ME/CFS Twitter page [Internet]. [place unknown]; PT/OT 4 ME/CFS;2020 July. Thanks @Aaslavit! $#MECSF is like watching a car wreck happening we can’t stop. 2020 Sept 06 [cited 2020 Oct 17]; [about 1 screen]. Available from @PTOT4MECFS on Twitter.

- ↑ World.physio. [cited 2020o Sep 30]. Available from: https://world.physio/sites/default/files/2020-07/COVID19-Briefing-Paper-2-Rehabilitation.pdf

- ↑ The medical system should have been prepared for long COVID [Internet]. Vice.com. [cited 2021m Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.vice.com/en/article/qjpywp/the-medical-system-should-have-been-prepared-for-long-haul-covid-patients-symptoms