Introduction to Cerebral Visual Impairment and Cerebral Palsy

Original Editor - Ewa Jaraczewska based on the course by Angela Kiger

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Cerebral visual impairment (CVI) can occur in children with cerebral palsy (CP) or developmental delay.[1] Children with CVI are frequently diagnosed with cerebral palsy. Despite the importance of early diagnosis, there is no standardised assessment tool to diagnose CVI. Nor is there one referral criteria guideline.[1] The challenge in early diagnosis relates to the wide range of visual dysfunctions present in CVI. These include central and peripheral vision dysfunction, dysfunctions in movement perception, gaze control, visual guidance of movement, visual attention, attentional orientation in space, visual analysis and recognition, visual memory and spatial cognition. These impairments can all affect a child's learning and social interactions.[2] This article presents an overview of CVI and its relationship with cerebral palsy.

Definitions[edit | edit source]

Cerebral Visual Impairment[edit | edit source]

Cerebral Visual Impairment (CVI) is “a verifiable visual dysfunction, which cannot be attributed to disorders of the anterior visual pathways or any potentially co-occurring ocular impairment.”[3]

Cerebral Palsy[edit | edit source]

Cerebral Palsy (CP) "describes a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture causing activity limitation, which is attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain."[4]

Brain Involvement in Vision[edit | edit source]

"It is estimated that over 50% of the brain is involved in vision processing."[5] -- Angela Kiger

The following example of a child catching a ball explains how the brain controls eyesight.[5][6][2]

- The child sees the ball.

- The frontal lobe decides on the action of catching the ball and its strategy.

- The occipital lobe processes the information received through the eyes. It passes the processed image data to the posterior parietal lobes via the superior longitudinal fasciculi.

- The middle part of the temporal lobe supports this process, with the posterior thalamus and superior colliculi, facilitating visual search and visual guidance of movement.

- The ball is identified and chosen as the target.

- The parietal lobe gauges the distance between the child's hands and the ball. If this is not the child's first time catching a ball, the temporal lobe takes part in the process as it controls memory. It subconsciously reminds the child that their hands are used to catch a ball, that they need to reach out, and that their body needs to adjust.

- The temporal lobes process local and detailed visual feedback via a bundle of nerve fibres on each side.

- The cerebellum helps the child adjust the timing of their actions and their balance.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- CVI affect at least 3.4% of children. However, the number may be higher as many affected children go unidentified.[7]

- More than 50% of children with learning difficulties who attend special schools have CVI.[7]

- CVI is present in 2 per 1000 live births. It is present in 19 per 1000 live births for infants born at 20-27 weeks gestation; subcortical damage is more common in preterm infants.[8][9]

- It is the most common cause of permanent vision loss in children aged 1-3 years old.[5]

- Almost 50% of children diagnosed with a visual impairment have CVI. [5]

- 56% of individuals with CVI have additional disabilities.[5]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

CVI in children can occur in the prenatal, perinatal or postnatal periods.[10]

Prenatal (conception to birth):

- hydrocephalus

- congenital central nervous system malformation

Perinatal (starts at twentieth to twenty eighth week of gestation and ends one to fourth weeks after delivery) :

- hypoxic-ischaemic injury

- genetic/chromosomal disorders

- metabolic disorders

- infection during pregnancy

- neonatal hypoglycaemia

- medication during pregnancy

Postnatal (from birth to six to eight weeks after birth):

- meningitis

- encephalitis

- brain tumours

- cerebrovascular accident

- seizures

- periventricular leukomalacia

- cardiac arrest

- cranio-cerebral trauma

Brain Damage and CVI[edit | edit source]

Brain damage in patients with CVI can be categorised as subcortical, cortical or both. Brain lesions resulting in CVI can affect the following parts of the brain:

- the posterior visual pathways (the visual cortex of the occipital lobe)

- the optic chiasm ("part of the brain where the optic nerves cross"[11])

- lateral geniculate bodies (a structure in the thalamus)

- optic radiations ("key white matter structures that cross the temporal lobe"[12])

- primary visual cortices (part of the occipital lobe that processes visual information)

- the middle temporal lobes

- the visual association areas

The following video explains the role of the visual association areas:

Visual Impairments Associated with CVI[edit | edit source]

The symptoms of CVI and the severity of visual impairment vary in children. They can affect the following:[10]

- sensory visual function (enables an individual "to be aware of colour, light level, contrast, motion and other visual stimuli"[14])

- oculomotor function ("the ability to use the eyes systematically to efficiently scan and locate an object in the field of vision"[15])

- visual-motor function ("integration between visual perception and motor skills"[16])

- cognitive visual function (the ability to analyse and process visual information[17])

CVI can occur in isolation or in association with eye or optic nerve damage. The lack of vision tends to be profound when the thalamus is involved.

Children with CVI may present with the following:[5]

- often have a normal or near-normal eye examination

- have a history or presence of a neurological disorder

- demonstrate behavioural responses to visual stimuli unique to CVI

- have difficulty sustaining gaze

- their head is often tilted slightly forward and to the side

Behavioural Changes[edit | edit source]

Children diagnosed with CVI can demonstrate specific behavioural signs, including:[18]

- short visual attention span

- markedly fluctuating visual performances

- the need for time, environmental stability, and repetition of items to obtain the best response

CVI Classification[edit | edit source]

A medically-based CVI classification[19] identifies three subgroups:

- A1: selective visual perception and visuomotor deficits

- A2: more severe and broader visual perception and visuomotor deficits and variable visual acuity

- B: unable to perform psychological testing due to significant visual acuity reduction

CVI and Cerebral Palsy[edit | edit source]

- CVI is common in children affected by CP[20]

- In medically-based CVI classification, most children with CP belong to the B subgroup.[20]

- The lesions which determine motor deficits in CP are "anatomically closely located to the distributed network of brain areas responsible for visual perception", and this helps explain the co-occurrence of CVI and CP.[21]

- The clinical spectrum of visual problems in children with CP is broad, ranging from mild to severe. It may include ophthalmological, oculomotor, basic visual function, and cognitive-visual disorders.[20]

- The intensity of visual impairment correlates with the severity of motor deficits:[22]

- children with tetraplegic CP present with:

- markedly reduced or not-assessable visual acuity

- highly impaired or absent oculomotor function

- a high percentage of ocular abnormalities

- children with diplegic CP present with:

- moderately reduced visual acuity

- altered contrast sensitivity

- absence of stereopsis

- impaired oculomotor abilities

- refractive errors and cognitive-visual disorders (CVDs)

- children with hemiplegic CP present with:

- slightly reduced visual acuity

- reduced visual field (frequently unilateral)

- altered stereopsis ("the ability to appreciate depth, due to the lateral displacement of the eyes providing two slightly different views of the same object"[23]).

- less frequent oculomotor involvement

- less frequent refractive errors

- children with tetraplegic CP present with:

Assessment and Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Admission Referral[edit | edit source]

Children are often referred to a specialist or specialists for assessment of visual impairment because:[1]

- the parents are concerned about the child's visual functioning

- they have an increased risk of CVI

- they have an intellectual disability or syndrome and can be screened for visual functioning

Multidisciplinary Team[edit | edit source]

A multidisciplinary team for CVI diagnostics is necessary for accurate and timely diagnosis. The team should include the following specialities at the minimum:

- paediatric ophthalmologist

- paediatric neurologist

- orthoptist or optometrist

- neuropsychologist

Follow-up Referral[edit | edit source]

The assessment results should be discussed with all members of the multidisciplinary team. Based on the outcome, the child can be referred to:[1]

- vision teacher and developmental therapist with a vision specialisation in CVI

- a rehabilitation centre or a specialised centre

- school for children with visual impairments if there is evidence of CVI

Assessment Tools[edit | edit source]

There is no standardised assessment tool for the diagnosis of CVI. The following assessment tools are recommended:[24]

- Questionnaires

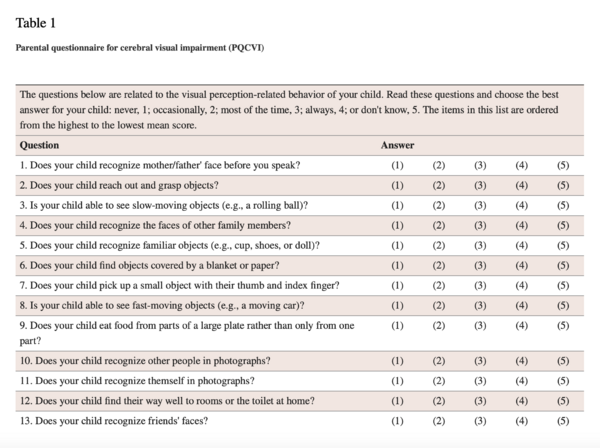

- Parental Questionnaire for Cerebral Visual Impairment (PQCVI) (see figure)

- The CVI Questionnaire: 46-item screening questionnaire[25]

- The Five Questions completed by a parent. A 5-point Likert Scale describes if the child ‘always’, ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘rarely’, or ‘never’ struggles with the described tasks[25]

- Functional vision assessment (CVI Range)

- "Behavioural assessment of functional vision, which defines the ability to interpret and react to visual information"[26]

- assessment based on observation, parent interview and direct assessment

- the evaluator grades the child on ten characteristics of CVI:[26]

- colour preference

- need for movement

- visual latency

- visual field preferences

- difficulties with visual complexity

- need for light

- difficulty with distance viewing

- atypical visual reflexes

- difficulty with visual novelty

- absence of visually guided reach

- scores range from 0 to 10 when 0 represents no functional vision, and 10 means typical or near typical functional vision

- Neuropsychological assessment of children with possible CVI

- no consensus in the diagnostic protocol

- Neuropsychological tests of visual perception[27]

- Eye tracking assessment[30]

- assessment of nystagmus, fixation, saccades, and pursuit

- Genetic assessment

- Neuroradiological evaluation and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- recording damage to those parts of the brain involved in visual processing

Multidisciplinary Team Approach in Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

"Vision leads movement (....). Ask questions about motivating visual stimuli to initiate gross motor tasks."[31] -- Erica Stearns

The role of the multidisciplinary team is to:[31]

- establish a child's unique vision

- choose strategies to make sure that the child's overall needs are being met

- prioritise goals (physical or occupational therapy goals before vision goal)

- example: working on balance or stabilisation prevents the child from visually fixating and attending to materials

- adjust the child's centre of vision and education materials as position changes

- example: during pressure relief time when the wheelchair is tilted backwards, a desktop computer screen must be adjusted

- choose an environment where the child can visually attend to materials and objects

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Baranello G, Signorini S, Tinelli F, Guzzetta A, Pagliano E, Rossi A, Foscan M, Tramacere I, Romeo DMM, Ricci D; VFCS Study Group. Visual Function Classification System for children with cerebral palsy: development and validation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020 Jan;62(1):104-110.

- Prechtl HF, Cioni G, Einspieler C, Bos AF, Ferrari F. Role of vision on early motor development: lessons from the blind. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001 Mar;43(3):198-201.

- CVI Range Assessment

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Boonstra FN, Bosch DGM, Geldof CJA, Stellingwerf C, Porro G. The Multidisciplinary Guidelines for Diagnosis and Referral in Cerebral Visual Impairment. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022 Jun 30;16:727565.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chokron S, Kovarski K, Dutton GN. Cortical Visual Impairments and Learning Disabilities. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021 Oct 13;15:713316.

- ↑ Sakki HEA, Dale NJ, Sargent J, Perez-Roche T, Bowman R. Is there consensus in defining childhood cerebral visual impairment? A systematic review of terminology and definitions. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018 Apr;102(4):424-432.

- ↑ Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, Dan B, Jacobsson B. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. 2007 Feb;109:8-14. Erratum in: Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007 Jun;49(6):480.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Kiger A. Cerebral Visual Impairment and Cerebral Palsy Course. Plus, 2023.

- ↑ Debrowski A. How does the brain control eyesight? (2020) Available from https://www.allaboutvision.com/resources/part-of-the-brain-controls-vision/ [last access 26.11.2023]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Williams C, Pease A, Warnes P, Harrison S, Pilon F, Hyvarinen L, West S, Self J, Ferris J; CVI Prevalence Study Group. Cerebral visual impairment-related vision problems in primary school children: a cross-sectional survey. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021 Jun;63(6):683-689.

- ↑ Robertson CM, Watt MJ, Dinu IA. Outcomes for the extremely premature infant: what is new? And where are we going? Pediatr Neurol. 2009 Mar;40(3):189-96.

- ↑ Hoyt CS, Fredrick DR. Cortically visually impaired children: a need for more study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998 Nov;82(11):1225-6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kozeis N. Brain visual impairment in childhood: mini review. Hippokratia. 2010 Oct;14(4):249-51.

- ↑ Ireland AC, Carter IB. Neuroanatomy, Optic Chiasm. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542287 [last access 26.11.2023]

- ↑ Rodrigues EM, Isolan GR, Becker LG, Dini LI, Vaz MAS, Frigeri TM. Anatomy of the optic radiations from the white matter fibre dissection perspective: A literature review applied to practical anatomical dissection. Surg Neurol Int. 2022 Jul 22;13:309.

- ↑ Neuro-Ophthalmology with Dr. Andrew G. Lee. Visual association cortex. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pD_kAQ6Et5Y[last accessed 26/11/2023]

- ↑ How the Visual Sensory System Works - HandsOn OT. Available from https://handsonotrehab.com/visual-sensory-system/ [last access 26.11.2023]

- ↑ What Are Oculomotor Skills? (2022). Available from https://llatherapy.org/what-are-oculomotor-skills/ [last access 26.11.2023]

- ↑ Stevens A, Bernier R. Visual-Motor Function. In: Volkmar, F.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer, New York, NY.

- ↑ Fazzi E, Bova S, Giovenzana A, Signorini S, Uggetti C, Bianchi P. Cognitive visual dysfunctions in preterm children with periventricular leukomalacia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009 Dec;51(12):974-81.

- ↑ Boonstra FN, Bosch DGM, Geldof CJA, Stellingwerf C, Porro G. The Multidisciplinary Guidelines for Diagnosis and Referral in Cerebral Visual Impairment. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022 Jun 30;16:727565.

- ↑ Sakki H, Bowman R, Sargent J, Kukadia R, Dale N. Visual function subtyping in children with early-onset cerebral visual impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021 Mar;63(3):303-312.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Galli J, Loi E, Molinaro A, Calza S, Franzoni A, Micheletti S, Rossi A, Semeraro F, Fazzi E; CP Collaborative Group. Age-Related Effects on the Spectrum of Cerebral Visual Impairment in Children With Cerebral Palsy. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022 Mar 2;16:750464.

- ↑ Tinelli F, Guzzetta A, Purpura G, Pasquariello R, Cioni G, Fiori S. Structural brain damage and visual disorders in children with cerebral palsy due to periventricular leukomalacia. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;28:102430.

- ↑ Fazzi E, Signorini SC, Piana RL, Bertrone C, Misefari W, Galli J, Balottin U, Bianchi PE. Neuro-ophthalmological disorders in cerebral palsy: Ophthalmological, oculomotor, and visual aspects. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 2012;54(8), 730-736.

- ↑ Macintyre-Béon C.Cerebral Visual Impairment in Children Born Prematurely. A thesis submitted to the University of Glasgow for the degree of M.Sc. (Med) Nursing and Health Care (Research).College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences University of Glasgow 2015

- ↑ Chang M, Borchert M. Methods of visual assessment in children with cortical visual impairment. Current Opinion in Neurology, 2021; 34(1):p 89-96.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Gorrie F, Goodall K, Rush R, Ravenscroft J. Towards population screening for Cerebral Visual Impairment: Validity of the Five Questions and the CVI Questionnaire. PLoS One. 2019 Mar 26;14(3):e0214290.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Chang M, Roman-Lantzy C, O’Neil SH, Reid MW, Borchet MS. Validity and reliability of CVI Range assessment for Clinical Research (CVI Range-CR): a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open Ophthalmology 2022;7:e001144.

- ↑ Lanca M, Jerskey BA, O'Connor MG. Neuropsychologic assessment of visual disorders. Neurol Clin. 2003 May;21(2):387-416.

- ↑ Spencer RJ, Wendell CR, Giggey PP, Seliger SL, Katzel LI, Waldstein SR. Judgment of Line Orientation: an examination of eight short forms. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35(2):160-6.

- ↑ Zhang X, Lv L, Min G, Wang Q, Zhao Y, Li Y. Overview of the Complex Figure Test and Its Clinical Application in Neuropsychiatric Disorders, Including Copying and Recall. Front. Neurol.,2021;12.

- ↑ Kooiker MJ, Pel JJ, Verbunt HJ, de Wit GC, van Genderen MM, van der Steen J. Quantification of visual function assessment using remote eye tracking in children: validity and applicability. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016 Sep;94(6):599-608.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Stearns E. Effective collaboration between physical therapists and teachers of visual impairments who are working with students with multiple disabilities and visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness , 2017;111(2).