Low Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders

Original Editors - Jeroen Verwichte

Top Contributors - Aimee Tow, Axel Antoine, Jeroen Verwichte, Haegeman Nicolas, Loïc Byl, Charlotte Fastenaekels, Admin, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Ian Duerinckx, Leon Chaitow, Evan Thomas and Oyemi Sillo

Search strategy[edit | edit source]

Database: pubmed, web of science and pedro <span style="font-size: 9pt; font-family: Verdana; color: windowtext;" />Keywords: “ Low back pain”, “ Breathing disorder”, “physiotherapy”, “yoga”, “ breathing therapy”, “ breathing exercises”, “ inspiratory training” ==

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

There are different definitions of low back pain:

The World Health Organization says low back pain is neither a disease nor a diagnostic entity of any sort. Low back pain refers to pain of variable duration in an area of the anatomy afflicted so often that it has become a paradigm of responses to external and internal stimuli.[1]

The Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF) defines low back pain as a term that refers to ‘non-specific low back pain’, which is defined as low back pain that does not have a specified physical cause, such as nerve root compression (Lumbar Radiculopathy), trauma, infection or the presence of a tumor. This is the case in about 90% of all low back pain patients. In 80–90% of cases, patients their complaints diminish spontaneously within 4–6 weeks. Approximately 65% of patients who consult their primary care physician are free of symptoms after 12 weeks. Recurrent low back pain is common.[2]

A breathing pattern disorder is defined as hyperventilation or over-breathing that does not occur as a result of an underlying pathology. a level 2B study[3] has shown that the presence of respiratory disease such as a breathing pattern disorder is a strong predictor for lower back pain. Stronger than other established risk factors.

De Groot said a breathing pattern disorder is defined as chronic or recurrent changes in the breathing pattern, contributing to respiratory and nonrespiratory complaints. Symptoms are: dyspnoea with normal lung function, chest tightness, chest (and other musculoskeletal) pain, deep sighing, exercise induced breathlessness, frequent yawning and hyperventilation.[4]

What is defined as a normal breathing pattern:

• Abdominal, not chest breathing should initiate inhalation, which then expand outwards during inhalation.

• Lifting the chest up while breathing is faulty

• Lack of or a upwards lateral lifting pattern is faulty

• Paradoxical breathing is faulty

• Breathing that has no clavicular grooving formed by chronic chest lifting

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

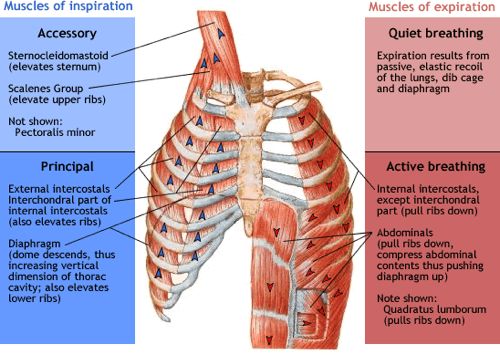

The thoracic cage is formed by the spine, rib cage and associated muscles. While the spine and the ribs form the sides and the tops, the diaphragm forms the floor of the thoracic cage. The muscles connecting the twelve pairs of ribs are called the intercostal muscles, and the muscles running from the head and neck to the sternum and the first two ribs are the sternocleidomastoids and the scalenes.

Muscles used for ventilation:

- Inspiratory muscles: external intercostals, diaphragm, sternocleidomastoids, scalenes

- Expiratory muscles: internal intercostals and the abdominal muscles (expiration during quiet breathing is called passive expiration, because it involves passive elastic recoil)[5] [6]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Breathing pattern disorders are because of hormonal influences (progesterone stimulates respiration) female dominated with a female to male ratio ranging from 2:1 to 7:1

Currently, there isn’t a consensus as to the scale of breathing pattern disorders in the general population, but a pilot study [7] examined the relationship between BPD and musceloskeletal pain and showed that 75% of those examined showed faulty breathing patterns. Although interesting, this study has several limitations. It was not designed or intended to be a reliability study. Its methods have no proven reliability. Future research is needed to validate the inter-examiner reliability of the methods of assessing breathing mechanics and the criteria of normal and faulty patterns of respiration. But if this numbers reflect to the general population, there is a 3 in 4 chance that your patient will have faulty breathing patterns.

Charactersitics/Clinical presentation

[edit | edit source]

== Functional

movement is defined as the ability to produce and maintain an adequate balance

of mobility and stability along the kinetic chain while integrating fundamental

movement patterns with accuracy and efficiency. Postural control deficits, poor

balance, altered proprioception, and inefficient motor control have been shown

to contribute to pain, disability, and interfere with normal movement.

Identification of risk factors that lead to these problems and contribute to

dysfunctional movement patterns could aid injury prevention and performance.[23[24]]<o:p></o:p>

==

Abnormal breathing patterns noted by George Yuan et al.

- Thoracoabdominal paradox: this refers to the asynchronous movement of the thorax and abdomen that can be seen with respiratory muscle dysfunction and increased work of breathing. This can be seen as a pure paradox where the thorax and abdomen are moving in opposite directions at the same time.

- Kussmaul’s breathing: this refers to a pattern with regular increased frequency and increased tidal volume and can often be seen to be gasping. Severe metabolic acidosis is often seen.

- Apneustic breathing: this refers to breathing where every inspiration is followed by an prolonged inspiratory pause and each expiration is followed by a prolonged expiratory pause. This expiratory pause is often mistaken for an apnea. The cause is damage to the respiratory center in the upper pons. - Cheyne stokes respiration: this refers to a cyclical crescendo-descrescendo pattern of breathing. This is followed by periods of central apnea. This is often seen in patients with stroke, brain tumor, traumatic brain injury, carbon monoxide poisoning, metabolic encephalopathy, altitude sickness, narcotics use and in non-rapid eye movement sleep of patients with congestive heart failure

- Ataxic and Biot’s breathing: these are forms of breathing that are sometimes lumped together and usually are related to brainstem strokes or narcotic medications. Ataxic breathing refers to breathing with irregular frequency and tidal volume interspersed with unpredictable pauses in breathing of periods of apnea. Biot’s breathing refers to a high frequency and regular tidal volume breathing interspersed with periods of apnea

- Agonal breathing: this refers to a pattern of irregular and sporadic breathing with gasping seen in dying patients before their terminal apnea. This form of breathing is inadequate to sustain life.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Abnormal breathing patterns are

often combined with musculoskeletal disorders. Individuals with poor posture, scapular dyskinesis, neck pain, temporomandibular joint pain and also low back pain exhibit signs of faulty breathing mechanisms.[29] <o:p></o:p>

Over activity of the accessory muscles (sternocleidomastoid, upper trapezius, and scalene muscles), whom induces thoracic breathing, have been linked to neck pain, scapular dyskinesis and trigger point formation.[29] Poor coordination of the diaphragm may result in compromised stability of the lumbar spine, altered motor control and dysfunctional movement patterns.[32]<o:p></o:p>

In addition to only checking the influence of a breathing pattern disorder affecting musculoskeletal regions (in this case the lower back), it is necessary to also make the differential diagnosis of what could lead to the low back pain besides the BPD. <o:p></o:p>

Low back pain is typically classified as being ‘specific’ or ‘non-specific’. Specific low back pain is defined as symptoms caused by specific patho-physiological mechanism, such as:

- hernia

- nuclei pulposi

- infection

- inflammation

- osteoporosis

- rheumatoid arthritis

- fracture

- tumour

Non-Specific low back pain is defined as symptoms without clear specific cause, i.e. low back pain of unknown origin. Approximately 90% of all low back pain patients will have non-specific low back pain. Nowadays there still don’t exist a reliable and valid classification system for the large majority of non-specific low back pain. The most important symptoms are pain and disability.<o:p></o:p>

[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnostic procedure for low back pain is mainly focused on the triage of patients with specific or non-specific low back. The triage is used to exclude specific pathology and nerve root pain.[8] Actually you can see breathing therapy as an additional therapy, but not as the main goal of your therapy.[9]

There are characteristics for recognizing and diagnosing breathing pattern disorders:[10]

• Restlessness (type A, “neurotic”)

• ‘Air hunger’

• Frequent sighing

• Rapid swallowing rate

• Poor breath-holding times

• Poor lateral expansion of lower thorax on inhalation

• Rise of shoulders on inhalation

• Visible “cord-like” sternomastoid muscles

• Rapid breathing rate

• Obvious paradoxical breathing

• Positive Nijmegen Test score (23 or higher)

• Low end-tidal CO2 levels on capnography assessment (below 35mmHg)

• Reports of a cluster of symptoms such as fatigue, pain (particularly chest, back and neck), anxiety, ‘brain-fog’, irritable bowel or bladder, paresthesia, cold extremities.

If a Patient has low back pain in combination with one of these characteristics, breathing therapy is advised.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (also see Outcome Measures Database)

Examination[edit | edit source]

BPD is diagnosed using physical assessment, a validated questionnaire (the Nijmegen) and a capnometer (measures respiratory Co2 levels)

- Nijmegen questionnaire provides a non-invasive test of high sensitivity (up to 91%) and specificity (up to 95%). a score of 23 out of 64 on the test suggest a positive diagnose of hyperventilation syndrome.

- Capnography have been shown to have a good concurrent validity when compared to arterial CO2 measures and can provide acces to this very important physiological information[11]

Because previous studies of breathing therapy have not included capnography in their research, it’s difficult to say anything about the validity of the device in function of therapy [12]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

add text here

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Studies have shown that eight weeks inspiratory muscle training in individuals with LRP to a training resistance of 60% of the 1RM leads to a significant improvement in inspiratory muscle strength, a more multi-segmental postural control strategy, increased inspiratory muscle strength and decrease of LBP severity. [16] [25]

According to following article of Wolf E. Mehling et al, examined the effect of breathing therapy on low back pain. However changes in pain and disability were comparable to those resulting from extended physical therapy. They compared the effects of breathing therapy with the effect of physical therapy. Each group received one introductory evaluation sessions of 60 minutes and 12 individual therapy sessions of equal duration, 45 minutes over 6 to eight weeks. The breath therapy was given by 5 certified breath therapists. Physical therapy was given by experienced physical therapy faculty members in the Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science.[17

The 90/90 bridge with ball and balloon technique was designed to help restore the ZOA (Zone of Apposition) and spine to a proper position in order to allow the diaphragm optimal ability to perform both its respiratory and postural roles. It's a therapeutic exercise that promotes optimal posture and neuromuscular control of the deep abdominals, diaphragm, and pelvic floor would be desirable for patients with breathing disorders en patients with LBP. The balloon blowing exercise (BBE) technique is performed in supine with the feet on a wall, hips and knees at 90 degrees and a ball between the knees. This passive 90˚ hip and knee flexion position places the body in relative lumbar spine flexion, posterior pelvic tilt and rib internal rotation/depression which serves to optimize the ZOA

and discourage lumbar extension/anterior pelvic.[16]

Studies of the effects of a single BBE and/or training effects of multiple BBE’s could include EMG for abdominal muscle, spirometry for changes in breathing parameters, real time ultrasound for diaphragm length and/or changes in abdominal muscle thickness. Additionally, future studies designed to describe changes in pain and function attributable to the BBE are needed to investigate the clinical efficacy of this promising therapeutic exercise technique.[28

According to following article, Laurie McLaughlin et al, breathing retraining should improve end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2), pain and function in most patients complaining of neck or back pain.

Poor breathing profiles were found in patients with neck or back pain: high respiratory rate, low CO2, erratic non-rhythmic patterns and upper chest breathing.

Exercises

According to the article by Laurie McLaughlin et al, breathing retraining should improve end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2), pain and function in most patients complaining of neck or back pain.(14)

Abdominal Breathing Technique:

How it’s done: With one hand on the chest and the other on the belly, take a deep breath in through the nose, ensuring the diaphragm (not the chest) inflates with enough air to create a stretch in the lungs. The goal: Six to 10 deep, slow breaths per minute for 10 minutes each day to experience immediate reductions to heart rate and blood pressure (34)(37)

The three-part breath:

The patiënt lies down on the back with the eyes closed, relaxing the face and the body. Then begin to inhale deeply through the nose. On each inhale, fill the belly up with your breath. Expand the belly with air like a balloon. On each exhale, expel all the air out from the belly through your nose. Draw the navel back towards your spine to make sure that the belly is empty of air. (14)

On the next inhale, fill the belly up with air as described before. Then when the belly is full, draw in a little more breath and let that air expand into the rib cage causing the ribs to widen apart. with the exhale, let the air go first from the rib cage, letting the ribs slide closer together, and them from the belly, drawing the navel back towards the spine. On the next inhale, fill the belly and rib cage up with air as described above. Then draw in just a little more air and let it fill the upper chest. On the exhale, let the breath go first from the upper chest, then from the rib cage, letting the ribs slide closer together. Finally, let the air go from the belly, drawing the navel back towards the spine.(37)(34)

Breathing excercises in combination with strenght training:

The following excercises39 are performed with a powerbreathe KH1 device. This handheld device applies a variable resistance provided by an electronically controlled valve (variable flow resistive load). Loading is maintained at the same relative intensity throughout the breath, by reducing the absolute load to accommodate the pressure–volume rela- tionship of the inspiratory muscles. The application of a tapered load allows patients to get close to maximal inspiration, even at high-training intensities.

Performing excercises for training the backmuscles in combination with this device can increase the muscle strength of the inspiratory muscles and also the muscles of the back. 38

Excercise 139

Stand on one leg with the device in the mouth and with one arm extended above you holding the resistance ( cable machine or resistance band).

Make sure that you have a straight body line between your ankle and shoulders, that you have a neutral spine and that your abdominal corset muscles are braced. Flex forward, rotating at the hip and inhale forcefully through the device. Exhale as you retrn to the upright start position. You can swap breathing phases between sets

You can make tis excercise more dificult by using more weight at the cable machine. You can also increase the resistance of the device.

2 sets with 15 repetitions.

Excercise 239

Begin with your feet shoulder width apart and with the device in the mouth. Hold the resistance (cable cord or resistance band) in one hand, with your hand near your shoulder.<o:p></o:p>

Make sure you have a neutral spine and brace your abdominal corset muscles.<o:p></o:p>

Press the handle of the cable away from you., lunging forward. As you move forward, inhale forcefullu through the device and exhale when you return back to the upright start position. You can swap breathing phases between sets. <o:p></o:p>

You can make tis excercise more dificult by using more weight at the cable machine. You can also increase the resistance of the device.

2 sets with 15 repititions.

Excercise 339

Begin with a lean position on your toes and on your arms. Hold your hands together. Hold the divice in your mouth.

Make sure you have a neutral spine and brace your abdominal corset muscles.

Hold this position for 30 seconds while you breath through the device.

You can make this excercise more dificult by bringing one leg to your body and return it afterwards. You repeat this with the other leg during the excercise.

You can also increase the resistance of the device.

3 sets

Excercise 439

Lie down on your back and keep your arms at your sides. Hold the device in your mouth. Lift your hips towards the ceiling while you make sure that you brace the abdominal corset muscles. Also make sure you keep your knees and thighs parallel. Hold this for 30 seconds while you breath through the device.

You can make this excercise more dificult by raising one leg during the excercise and bring it back to the ground. you can do this alternating with the other leg.

You can also increase the resitance of the device.

Key Research[edit | edit source]

One level 1B RCT [13] studied the effects of breathing therapy on chronic low back patients. Patients improved significantly with breathing therapy. The changes in standard low back pain measures of pain and disability were comparable to those resulting from high-quality, extended physical therapy

There is also a review that describes the relationship between low back pain and breathing pattern disorders[14]. The review states that there is evidence of a weak but statistically significant positive correlation between low back pain and respiratory problems. All the studies in this review were cross sectional 2A level cohort studies.

In one case serie [11] of 24 patient with low back or pelvic pain, they all showed an altered respiratory chemistry. Breathing dramatically improved with breathing retraining (all but one reached normal ETCO2 values). 75% of the patients reported improvements in pain, 50% reported improvements in functional activity. These results were both clinically important and statistically significant.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Janssens L, Brumagne S, Polspoel K, Troosters T, McConnell A. The effect of inspiratory muscles fatigue on postural control in people with and without recurrent low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010 May 1;35(10):1088-94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bee5c3.

Janssens L, Brumagne S, McConnell AK, Hermans G, Troosters T, Gayan-Ramirez G. Greater diaphragm fatigability in individuals with recurrent low back pain. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013 Aug 15;188(2):119-23. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.028. Epub 2013 May 31.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Breath therapy would provide a short-term improvement in pain and related functional limitations, but in the longer term one has to deal with a major downturn which it is not significantly better than conservative physiotherapy. Other research has shown that yoga is more effective than a self-care book, but there is only weak evidence that it is more effective than physical exercises.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1-UFW4KkLsPjVlBi3wM7t-SugMHpfpN_BxFjjpTPdh2a4sKsAe|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2003;81:671-676

- ↑ National practice guidelines for physical therapy in patients with low back pain GE Bekkering PT MSc,I, VI HJM Hendriks PT PhD,I, VII BW Koes PhD,II RAB Oostendorp PT MT PhD,I, III, IV RWJG, Ostelo PT MSc,VI JMC Thomassen PT,V MW van Tulder PhD.V, KNGF-guidelines for physical therapy in patients with low back pain.

- ↑ Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW. Disorders of breathing and continence have a stronger association with back pain than obesity and physical activity. Aust J Physiother 2006;52:11–6.(2B)

- ↑ de Groot EP 2011 Breathing abnormalities in children with breathlessness. Respiratory Reviews 12 (2011) 83–87

- ↑ B.R. Johnson, W.C. Ober, C.W. Garrison, A.C. Silverthorn. Human Physiology, an integrated approach, Fifth edition. Dee Unglaub Silverthorn, Ph.D.

- ↑ Theodore A. Wilson and Andre De Troyer. diaphragm Diagrammatic analysis of the respiratory action of the. J Appl Physiol 108:251-255, 2010. First published 25 November 2009; doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00960.2009(A1)

- ↑ Perri MA, Halford E. Pain and faulty breathing: a pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2004;8:297–306

- ↑ B. W. Koes, M. W. van Tulder, S Thomas, Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain, British Medical Journal, Volume 332, 2006 (3A)

- ↑ Nancy ZI, The Art of Breathing:6 Simple Lessons to Improve Performance, Health, and Well-Being , North Atlantic Books , 2000 , p. 182

- ↑ L. Chaitow ,Breathing Pattern Disorders and Lumbopelvic pain and Dysfunction, march 20 , www.leonchaitow.com (5)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Laurie McLaughlin, Charlie H. Goldsmith, Kimberly Coleman. Breathing evaluation and retraining as an adjunct to manual therapy. Manual therapy, volume 16, Issue 1, pages 51-52 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "MC" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ J. S. Gravenstein,Michael B. Jaffe,David A. Paulus. Capnography: clinical aspects : carbon dioxide over time and volume. Br. J. Anaesth. (May 2005) 94 (5): 695-696. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei539

- ↑ Mehling WE, Hamel KA, Acree M, Byl N, Hecht FM. Randomized, controlled trial of breath therapy for patients with chronic low-back pain, Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2005 Jul-Aug;11(4):44-52 (1B)

- ↑ Lise Hestbaek, DC,a Charlotte Leboeuf-Yde, DC, MPH, PhD,b and Claus Manniche, DrMedScc . IS LOW BACK PAIN PART OF A GENERAL HEALTH PATTERN OR s IT A SEPARATE AND DISTINCTIVE ENTITY?A CRITICAL LITERATURE REVIEW OF COMORBIDITY WITH LOW BACK PAIN. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003 May;26(4):243-52. (2A)