Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

Original Editors - Katelyn Koeninger and Kristen Storrie from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project and Yves Hubar

Top Contributors Katelyn Koeninger, Kristen Storrie, Laura Ritchie, Laure-Anne Callewaert, Yves Hubar, Angeliki Chorti, Admin, Melissa Coetsee, Evan Thomas, Scott Cornish, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Gayatri Jadav Upadhyay, Gwen Wyns, Matthias Steenwerckx, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Claire Knott, Lauren Lopez, Jo Etherton, Maria Galve Villa, Michelle Lee, Richmond Stace, WikiSysop, Wendy Walker and Naomi O'Reilly

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a term for a complex pain disorder characterised by continuing (spontaneous and/or evoked) regional pain that is seemingly disproportionate in time or degree to the usual course of any known trauma or lesion[1]. Specific clinical features include allodynia, hyperalgesia, sudomotor and vasomotor abnormalities, and trophic changes.

CRPS has a multifactorial pathophysiology involving pain dysregulation in the sympathetic and central nervous systems, and possible genetic, inflammatory, and psychological factors.

Many names have been used to describe this syndrome such as; Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, causalgia, algodystrophy, Sudeck’s atrophy, neurodystrophy and post-traumatic dystrophy. To standardise the nomenclature, the name complex regional pain syndrome was adopted in 1995 by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).[2]

Classification[edit | edit source]

CRPS is subdivided into Type I and Type II CRPS. Type I occurs in the absence of major nerve damage, while Type II occurs following major nerve damage.[3]Despite this distinction, there is a large overlap in clinical features and the primary diagnostic criteria are identical, and therefore may have little clinical importance.[1]

In the past, three stages of CRPS progression have been cited, but studies have found that the existence of these stages are unsubstantiated.[1] It is however possible for CRPS subtypes to evolve over time, currently referred to as "warm CRPS" (warm, red, dry and oedematous extremity) and "cold CRPS" (cold, blue, sweaty and less oedematous). Both these subtypes present with comparable pain intensity. Warm CRPS is by far the most common in early CRPS, and cold CRPS tends to have a worse prognosis.[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

CRPS incidence appears to vary according to global location. For example, studies show that Minnesota has an incidence of 5.46 per 100,000 person-years for CRPS type I and 0.82 per 100,000 person-years for CRPS type II, whilst the Netherlands in 2006 had 26.2 cases per 100,000 person-years. Research shows that CRPS is more common in females than males, with a ratio of 3.5:1.[4] CRPS can affect people of all ages, including children as young as three years old and adults as old as 75 years, but typically is most prevalent in the mid-thirties. CRPS Type I occurs in 5% of all traumatic injuries, with 91% of all CRPS cases occurring after surgery.[5]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

CRPS may affect any part of the body, but occurs most often in the extremities. The wrist is most frequently affected after distal radial fractures.[6]

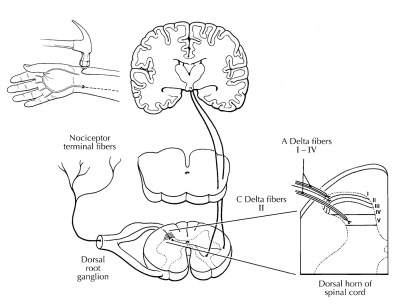

The central and peripheral nervous systems are connected through neural and chemical pathways, and can have direct control over the autonomic nervous system. It is for this reason that there can be changes in vasomotor and sudomotor responses without any impairment in the peripheral nervous system. Pain, heat, and swelling are usually not located at the site of injury and there may be no clear damage. Central sensitisation is seen as a main cause for developing CRPS.[7][8]

Figure 1.Nociceptive (painful) information is relayed through the dorsal horn of the spinal cord for processing and modulation before cortical evaluation. [9]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Complex regional pain syndrome can develop after the occurrence of different types of injuries, such as:

- Sprains and strains

- Surgeries

- Fractures

- Contusions

- Crush injuries

- Nerve lesions

- Stroke

The provoking injury may sometimes occur spontaneously; other times, it can not be determined.[10][11][12][13]. One study found that 56% of patients felt their CRPS was due to an ‘on the job’ injury, with the most common type of work-related injury occurring in service employments, such as in restaurants, bakeries, and police offices.[14]

The location of CRPS varies from person to person, mostly affecting the extremities, occurring slightly more in the lower extremities (+/- 60%) than in the upper extremities (+/- 40%). It can also appear unilaterally or bilaterally, [11][12] regularly in young adults and more frequently in females than males.[15]

The onset is mostly associated with a trauma, immobilisation, injections, or surgery, but there is no relation between the grade of severity of the initial injury and the following syndrome. A stressful life and other psychological factors may be potential risk factors that impact the severity of symptoms in CRPS. [15]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The differences between Type I and Type II are based on a consensus between clinicians and scientists. The definition of Type II (see below) is open to interpretation. For example, post-traumatic neuralgia has different syndromes with different underlying mechanisms, but it can be included in type II. Hence the definition of both types needs to be improved. In both cases, it can be assumed that long-term central changes have occurred. Changes in the somatosensory, sympathetic, peripheral, somatomotor, and neuroendocrine systems can cause changes in the central nervous system. All symptoms of Type II show many similarities to those of Type I. [7][16][17][18]

CRPS is clinically characterised by sensory, autonomic, and motor disturbances. The table below shows an overview of the different characteristics of CRPS Types I and II. [2] [7] [13] [17] [18] [19]

| TYPE | ||

| Definition |

|

|

| Etiology |

|

|

| Sensory disturbances |

|

|

| Autonomic disorders + inflammatory symptoms |

| |

| Trophic changes |

|

|

| Motor dysfunction |

| |

| Pain (Sympathetic Nervous System) |

|

Symptoms can spread beyond the area of the lesioned nerve in Type II. Ongoing neurogenic inflammation, vasomotor dysfunction, central sensitisation and maladaptive neuroplasticity contribute to the clinical phenotype of CRPS. Genetic and psychological factors can influence the vulnerability to CRPS and also affect the mechanisms that maintain CRPS. Peripheral and central changes can be irreversible. The sympathetic nervous system plays a key role in maintaining pain and autonomic dysfunction in the affected extremity. [12][17]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

CRPS may also be associated with:

- Impaired microcirculation [21]

- Asthma [4]

- Bone Fractures [20]

- Cellulitis [22]

- Conversion Disorder [23]

- Depression/Anxiety

- Factitious Disorder

- Lymphedema [21]

- Malignancy [24]

- Migraines [4]

- Nerve Entrapment Syndromes

- Osteomyelitis

- Osteoporosis [4][20]

- Peripheral Neuropathies

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Scleroderma

- Septic arthritis

- Autoimmunity [25]

- Tenosynovitis

- Thrombophlebitis

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis includes the direct effects of the following conditions: [5][26]

- Bony or soft tissue injury

- Peripheral neuropathy, nerve lesions

- Arthritis

- Infection

- Compartment syndrome

- Arterial insufficiency

- Raynaud’s Disease

- Lymphatic or venous obstruction

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS)

- Gardner-Diamond Syndrome

- Erythromelalgia

- Self-harm or malingering

- Cellulitis

- Undiagnostic fracture

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

CRPS diagnosis is mainly based on patient history, clinical examination, and supportive investigations.

There are 4 diagnostic tools for CRPS in adult populations. These include the Veldman criteria, IASP criteria, Budapest Criteria, and Budapest Research Criteria.[27]

The Budapest Criteria[edit | edit source]

The Budapest criteria (also known as the IASP criteria and explicitly endorsed by the IASP) has been developed for the diagnosis of CRPS, but improvements still need to be made. [28][29][30] Clinical diagnostic criteria for CRPS are:[1]

- Continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event

- Must report at least one symptom in three of the four following categories:

- Sensory: hyperalgesia and/or allodynia

- Vasomotor: temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin colour asymmetry

- Sudomotor/edema: edema and /or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/trophic: decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

- Must display at least one sign at the time of evaluation in two or more of the following categories

- Sensory: hyperalgesia (to pinprick) and/or allodynia (to light touch/pressure/joint movement)

- Vasomotor: evidence of temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin colour asymmetry

- Sudomotor/edema: evidence of edema and /or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/trophic: evidence of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

- There is no other diagnosis that better explains the signs and symptoms

The Budapest Criteria have excellent diagnostic sensitivity of 99% and a moderate specificity of 68%. [27]

Other Tests[edit | edit source]

Infrared Thermography[edit | edit source]

Infrared thermography (IRT) is an effective mechanism to find significant asymmetry in temperature between both limbs by determining if the affected side of the body shows vasomotor differences in comparison to the other side. It is reported having a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 89%. [32] This test is hard to obtain so it is not often used for diagnosing of CRPS. [29] [33][32]

Sweat Testing[edit | edit source]

Determining if the patient sweats abnormally. Q-sweat is an adequate instrument to measure sweat production. The sweat samples should be taken from both sides of the body at the same time. [7][32][34]

Radiographic Testing[edit | edit source]

Irregularities in the bone structure of the affected side of the body can become visible with the use of X-rays. If the X-ray shows no sign of osteoporosis, CRPS can be excluded if the patient is an adult. [7] [32]

Three Phase Bone Scan[edit | edit source]

A triple phase bone scan is the best method to rule out Type I CPRS. [35] With the use of technetium Tc 99m-labeled bisophosphonates, an increase in bone metabolism can be shown. Higher uptake of the substance means increased bone metabolism and the body part could be affected. [32] The triple-phase bone scan has the best sensitivity, NPV, and PPV compared to MRI and plain film radiographs.

Bone Densitometry[edit | edit source]

An affected limb often shows less bone mineral density and a change in the content of the bone mineral. During treatment of the CPRS the state of the bone mineral will improve. So this test can also be used to determine if the patient’s treatment is effective. [32]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)[edit | edit source]

MRI scans are useful to detect periarticular marrow oedema, soft tissue swelling and joint effusions. And in a later stage, atrophy and fibrosis of periarticular structures can be detected. But these symptoms are not exclusively signs of CRPS. [7][32]

Sympathetic Blocks[edit | edit source]

If the patient shows vasomotor or sudomotor dysfunction and severe pain, blocking the sympathetic nerves proves to be an effective technique to evaluate if the sympathetic nervous system is causing the pain to remain. This technique requires local anesthetic or ablation and is successful if at least 50% of the pain is reduced. [32]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The CRPS consortium has established a list of core outcome measures to be used for patients with CRPS (referred to as COMPACT).

Patient reported Outcome Measures:

- PROMIS-29: Assesses 7 domains (physical function, pain interference, fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep, social participation)

- NPRS: Numeric pain rating scale

- Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2): Six neuropathic items capture pain quality

- Pain Catastrophising Scale

- EQ-5D-5L: Measurement of health state

- Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire

- CRPS symptom questions: Derived from the Budapest Criteria

Clinical reported Outcome Measures:

- CRPS Severity Score (CSS): Includes 8 signs and 8 symptoms that reflect the sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor/edema and motor/trophic disorders of CPRS, coded based on the history and physical examination. Extent of changes in CSS scores over time are significantly associated with changes in pain intensity, fatigue, and functional impairments. Thus, the CSS appears to be valid and sensitive to change. A change of 5 or more CSS scale points reflects a clinically-significant change[1]

Functional Outcome Measures (not part of COMPACT):

- Grip strength[36]

- Walking stairs[37]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation described above. Procedures start with taking a detailed medical history, taking into account any initiating trauma and any history of sensory, autonomic, and motor disturbances, as well as how the symptoms developed, the time frame, distribution and characteristics of pain. Assessment for any swelling, sweating, trophic and/or temperature increases, and motor abnormality in the disturbed area is important. Skin temperature differences may be helpful for diagnosis of CRPS. The original International Association for the Study of Pain criteria required only a history and subjective symptoms for a diagnosis of CRPS, but recent consensus guidelines have argued for the inclusion of objective findings. [38]

The examination of the affected limb is from the neck downwards and should be carried out at rest, during activity, and during ambulation. [39] Sensory, motor and autonomic dysfunctions are investigated. [38][39][40]

The clinical presentation of CRPS, and the underlying mechanisms, can differ between patients and even within a patient over time - it is therefore important assess underlying pain mechanisms in order to design targeted treatment for each individual.[1]

Autonomic Dysfunction[edit | edit source]

The majority of patients with CRPS have bilateral differences in limb temperature and the skin temperature depends of the chronicity of the disease. In the acute stages, temperature increases are often concomitant with a white or reddish colouration of the skin and swelling. where the syndrome is chronic, the temperature will decrease and is associated with a bluish tint to the skin and atrophy. [41]

Motor Dysfunction[edit | edit source]

Studies have shown that approximately 70% of the patients with CRPS show muscle weakness in the affected limb, exaggerated tendon reflexes or tremor, irregular myoclonic jerks, and dystonic muscle contractions. Muscle dysfunction often coincides with a loss of range of motion in the distal joints. [39]

Sensory Dysfunction[edit | edit source]

The distal ends of the extremities require attention when examining a patient with CRPS. However, common findings of regional neuropathic and motor dysfunction have shown us that it is important to broaden the examination both proximally and contralaterally. [41]

Light touch, pinprick, temperature and vibration sensation should be assessed for a complete picture of the CRPS. [41] Most assessments are interlinked, for example, when vibration sensation is highly positive, light touch should also be positive. [41]

To help distinguish the findings of a sensory dysfunction, bilateral comparisons are made. The results should be clear and reliable. [39][41]

Multidisciplinary Management[edit | edit source]

CRPS can be very difficult to treat successfully, as it involves both central and peripheral pathophysiology, as well as frequent psychosocial components.[1] This complexity of CRPS calls for an interdisciplinary approach, where the entire management team collaborates and focuses on all the relevant biopsychosocial elements. In many settings this is not feasible - in such cases a multidisciplinary approach is still very important to address the multifactorial nature of CRPS.[1] Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome should be immediate, and most importantly directed toward functional restoration. Functional restoration emphasises physical activity, desensitisation and normalisation of sympathetic tone, and involves steady progression. [1]

Treatment Overview[edit | edit source]

The following table summarises the treatment recommendations for CRPS. These strategies are based on the Malibu CRPS algorithm and more recent treatment guidelines[1]

| Functional Restoration | Description & Modalities | Team members |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Activation of pre-sensorimotor cortices | Graded motor imagery

Visual tactile discrimination |

PT/OT |

| Phase 2: Gentle active ROM | Progressive AROM

Isometric strengthening |

PT |

| Phase 3: Weight bearing | UL: carrying items

LL: partial weight bearing |

PT/OT |

| Desensitisation | Progressive stimulation with textures (soft to more rough)

Contrast baths with progressive broadening of the temp difference |

OT/PT |

| Pain Management | Sympathetic blocks and/or pain medication only if pain interferes with ability to engage with rehab progression | MD |

| Edema Management | General aerobic activity | PT/OT |

| Psychological approaches | CBT and exposure-based therapy if patient presents with kinesiophobia

Psychotherapy if depression/anxiety is present |

Psych/PT |

| Secondary impairments | Local muscle spasm, reactive bracing and disuse atrophy secondary to pain needs to be addressed | PT |

Progression of treatment[edit | edit source]

A gradual and steady progression can help to restore function without exacerbating symptoms

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Medications: Multiple medications agents are used in the management of CRPS. The usual medications include anti-inflammatory medications, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, transdermal lidocaine, opioids, NMDA antagonists, and bisphosphonates.

Interventions include: sympathetic blocks; spinal cord stimulations; dorsal root ganglion stimulation.[3]

| [42] |

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Various consensus groups have emphasised that physiotherapy is of utmost importance in restoring function in patients with CRPS[7][1]. Various studies have shown that exercise-based physiotherapy is effective in managing pain and reducing impairment. [1][43]

It is difficult to manage CRPS as there is a lack of understanding of the pathophysiologic abnormalities, a lack of specific diagnostic criteria and very low-quality evidence to treat CRPS. [16] The main goals of treatment are a reduction in pain, preservation of limb function and a return to work. Comorbidities such as depression, sleep disturbance, and anxiety also need to be addressed and treated concurrently in a patient-centred, multidisciplinary approach.

A combination of physical and occupational therapy is effective in reducing pain and increasing function in patients who have had CRPS for less than 1 year. [4] Physical therapy focuses on patient education about the condition and functional activities.

Physical therapy intervention could include any of the following:

- Graded Motor Imagery (GMI): Aims to address altered central processing by restoring the mismatch between afferent input and central representation. A meta-analysis demonstrated very good evidence for the efficacy of GMI in combination with medical management in patients with CRPS-1.[44]

- Mirror therapy: Proven to be effective in patients with CRPS-1 and for stroke patients with CRPS.[1] [45]

- Aquatic therapy allows activities to be performed with decreased weight bearing on the lower extremities.

- Desensitisation [4]

- Gradual weight bearing [4]

- Stretching [4]

- Fine motor control [4]

- TENS [46]

- Strengthening (isometric) and ROM exercises

It is important to recognise that CRPS typically follows blood vessel pathways, and therefore symptoms may not always follow neural patterns. As a result of the spread pattern, CRPS treatment should also be provided bilaterally, due to the contralateral connections present between the extremities.[20] Treatment should be based on basic principles of pain management (pain and symptom relief, supportive care, rehabilitation) and due to the lack of evidence in treatment of CRPS treatments are based around that of other neuropathic pain syndromes. [7][16]

Progression of treatment[edit | edit source]

A gradual and steady progression can help to restore function without exacerbating symptoms

Acute Phase[edit | edit source]

Immobilisation and contralateral therapy. Intensive active therapy in the acute phase can lead to deterioration. [7]

Chronic Phase[edit | edit source]

Passive physical therapy including manipulation, manual therapy, massage and mobilisations. [2] [16] Lymphatic drainage can be used to facilitate regression of oedema. [16] Tender areas are recommended to be treated in the following order: more severe before less severe, more proximal and medial before more distally and laterally located points and the area of greatest accumulation of tender areas is treated first. When tender areas are located in a row, the middle is treated first.[47]

Therapeutic exercise includes isometric strengthening therapy followed by active isotonic training in combination with sensory desensitisation programmes. [7] [16] Strength training includes exercises for all four extremities and the trunk. [48] Desensitisation programmes consist of giving stimuli of different fabrics, different pressures (light or deep), vibration, tapping, heat or cold. The exercises can be stress-loading (i.e. walking, carrying weights), endurance training and functional training. [48] When CRPS occurs in the lower extremities, gait re-training is recommended. [47]

Mirror therapy or mirror visual feedback [49]

Mirror therapy is where both hands are placed into a box with a mirror separating the two compartments and, whilst moving both hands, the patient watches the reflection of the unaffected hand in the mirror. [2]

There is some evidence to suggest that mirror therapy has the effect of:

- Reducing pain intensity and improving function in post-stroke CRPS [16] [45][50]

- A significant improvement in pain [16]

- Improving function (low-quality evidence, however) [16]

Graded motor imagery/learning is effective. [2][16][49][51] However, further trials are required. [2] [16]GMI plus medical management is more effective than medical management plus physiotherapy. [16] GMI may reduce pain and improve function. [51] Other therapies include relaxation, [49][1] cognitive-behavioral therapy, [43] deep breathing exercises and biofeedback.

Neuromodulation or Invasive Stimulation Techniques[edit | edit source]

Neuromodulation contains peripheral nerve stimulation with implanted electrodes, epidural spinal cord stimulation, deep brain stimulation and electrotherapy.[16] Electrotherapy includes transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS), [49] [52] spinal cord stimulation (SCS) [2][32][53] and non-invasive brain stimulation (repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation). [16] These techniques help to reduce pain, [16] although further trials are required. [2]

Other Treatments[edit | edit source]

- Whirlpool bath/ contrast baths [54]

- Vocational and recreational rehabilitation [16]

- Psychological therapies: cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), operant conditioning (OC), counselling, pain education and relaxation techniques [2] [16]

- Acupuncture, electroacupuncture [49]

- Tactile sensory discrimination training [16][50]

- Weight bearing [2]

- Ultrasound therapy

- Kinesio taping [55]

Occupational Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Desensitisation: Involves graded exposure to textures (from soft to more textured). Aids in normalisation of cortical organisation in CRPS patients by restoring the sensory cortex[1]

Psychotherapy[edit | edit source]

In CRPS, psychological factors are important to target to ensure optimal outcomes. Solely treating psychological aspects is however not sufficient, as clear biological elements exist in CRPS. The aim of psychological interventions should be to address any factors that interfere with functional progression and to assist the psychological impact of a continued, severe pain experience[1].

- CBT and exposure-based therapies: Particularly valuable, in combination with physiotherapy, to address kinesiophobia[1]

Children[edit | edit source]

In another study of 28 children meeting the IASP criteria for CRPS, 92% reduced or eliminated their pain after receiving exercise therapy [43]

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

Thoracic Spine Dysfunction in Upper Extremity Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I

Resources[edit | edit source]

- CRPS Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines, 5th Edition

- International Research Consortium for CRPS (IRC)

- Complex regional pain syndrome in adults (2nd edition) UK guidelines for diagnosis, referral and management in primary and secondary care. Royal College of Physicians, July 2018.

- Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association

- American Chronic Pain Association

- Mayo Clinic

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

CRPS is a term for a variety of clinical conditions characterised by chronic persistent pain. There are two types of CRPS and the difference between Types I and II is based on a consensus between clinicians and scientists. All symptoms of CRPS Type II show many similarities to those of CRPS I. It is difficult to manage CRPS as there is a lack of understanding of the pathophysiologic abnormalities and lack of specific diagnostic criteria along with very low-quality evidence to treat CRPS. Clinical studies demonstrate a significant improvement following physical therapy, but there need to be more trials to develop an optimal management programme.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 Harden RN, McCabe CS, Goebel A, Massey M, Suvar T, Grieve S, Bruehl S. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines. Pain Medicine. 2022 May 1;23(Supplement_1):S1-53.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Tran Q. Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: a review of the evidence. Can J Anesth. 2010 Feb;57(2):149-66.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Dey DD, Schwartzman RJ. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy). StatPearls;2012:07-6.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 Goebel A. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011 Oct;50(10):1739-50.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Turner-Stokes L, Goebel A. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults: concise guidance. Clin Med (Lond) 2011 Dec;11(6):596-600.

- ↑ Jellad A. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I: Incidence and Risk Factors in Patients With Fracture of the Distal Radius. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014 Mar; 95(3):487-92.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Baron R, Wasner G. Complex regional pain syndromes. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001 Apr;5(2):114-23.

- ↑ Shipton E. Complex regional pain syndrome – Mechanisms, diagnosis, and management. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2009; 20:209-14.

- ↑ Teasdall R, Smith BP, Koman LA. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). Clin Sports Med. 2004 Jan;23(1):145-55.

- ↑ Jänig W, Baron R.Complex regional pain syndrome: mystery explained? Lancet Neurol. 2003 Nov;2(11):687-97.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Allen G, Galer BS, Schwartz L. Epidemiology of complex regional pain syndrome: a retrospective chart review of 134 patients. Pain.1999 Apr;80(3):539-44.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Sumitani M, Yasunaga H, Uchida K, Horiguchi H, Nakamura M, Ohe K, Fushimi K, Matsuda S, Yamada Y. Perioperative factors affecting the occurrence of acute complex regional pain syndrome following limb bone fracture surgery: data from the Japanese Diagnosis Procedure Combination database. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014 Jul;53(7):1186-93.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Juottonen K, Gockel M, Silén T, Hurri H, Hari R, Forss N. Altered central sensorimotor processing in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2002 Aug;98(3):315-323.

- ↑ Allen G, Galer BS, Schwartz L. Epidemiology of complex regional pain syndrome: a retrospective chart review of 134 patients. Pain. 1999 Apr;80(3):539-44.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Raja SN, Grabow TS. Complex regional pain syndrome I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). Anesthesiology. 2002 May;96(5):1254-60.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 16.13 16.14 16.15 16.16 16.17 O'Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, Marston L, Moseley GL. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Apr 30;2013(4):CD009416.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Wasner G, Schattschneider J, Heckmann K, Maier C, Baron R. Vascular abnormalities in reflex sympathetic dystrophy (CRPS I): mechanisms and diagnostic value. Brain. 2001 Mar;124(Pt 3):587-99.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Jänig W, Baron R. Complex regional pain syndrome is a disease of the central nervous system. Clin Auton Res. 2002 Jun;12(3):150-64.

- ↑ Galer BS, Henderson J, Perander J, Jensen MP. Course of symptoms and quality of life measurement in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: a pilot survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000 Oct;20(4):286-92.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Hooshmand H, Phillips E. Spread of complex regional pain syndrome. Available from: https://www.rsdrx.com/Spread_of_CRPS.pdf [accessed 5/7/2023]

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Groeneweg G, Huygen F, Coderre T, Zijlstra F. Regulation of peripheral blood flow in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: clinical implication for symptomatic relief and pain management. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:116.

- ↑ Goebel A. Current Concepts in Adult CRPS. Rev Pain. 2011 Jun; 5(2): 3–11.

- ↑ Popkirov S, Hoeritzauer I, Colvin L, Carson AJ, Stone J. Complex regional pain syndrome and functional neurological disorders - time for reconciliation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019 May;90(5):608-14.

- ↑ Mekhail N, Kapural L. Complex regional pain syndrome type I in cancer patients. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4(3):227-33.

- ↑ Dirckx M, Schreurs M, de Mos M, Stronks D, Huygen F. The Prevalence of Autoantibodies in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I. Mediators Inflamm. 2015; 2015: 718201.

- ↑ Thomson McBride AR, Barnett AJ, Livingstone JA, Atkins RM. Complex regional pain syndrome (type 1): a comparison of 2 diagnostic criteria methods. Clin J Pain. 2008 Sep;24(7):637-40.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Mesaroli G, Hundert A, Birnie KA, Campbell F, Stinson J. Screening and diagnostic tools for complex regional pain syndrome: a systematic review. Pain. 2021 May;162(5):1295-1304.

- ↑ Harden NR, Bruehl S, Perez RSGM, Birklein F, Marinus J, Maihofner C, Lubenow T, Buvanendran A, Mackey S, Graciosa J, Mogilevski M, Ramsden C, Chont M, Vatine JJ. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the "Budapest Criteria") for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain. 2010 Aug;150(2):268-74.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Choi E, Lee PB, Nahm FS. Interexaminer reliability of infrared thermography for the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome. Skin Res Technol. 2013 May;19(2):189-93.

- ↑ Harden NR. The diagnosis of CRPS: are we there yet? Pain. 2012 Jun;153(6):1142-1143.

- ↑ Bia Education. Diagnostic criteria for CRPS. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FjZH7Fl1wLs [accessed 6/7/2023]

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 32.8 Albazaz R, Wong YT, Homer-Vanniasinkam S. Complex regional pain syndrome: a review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2008 Mar;22(2):297-306.

- ↑ Perez RS, Collins S, Marinus J, Zuurmond WW, de Lange JJ. Diagnostic criteria for CRPS I: differences between patient profiles using three different diagnostic sets. Eur J Pain. 2007 Nov;11(8):895-902.

- ↑ Chémali KR, Gorodeski R, Chelimsky TC. Alpha-adrenergic supersensitivity of the sudomotor nerve in complex regional pain syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2001 Apr;49(4):453-9.

- ↑ Cappello ZJ, Kasdan ML, Louis DS. Meta-analysis of imaging techniques for the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome type I. J Hand Surg Am. 2012 Feb;37(2):288-96.

- ↑ Hotta J, Harno H, Nummenmaa L, Kalso E, Hari R, Forss N. Patients with complex regional pain syndrome overestimate applied force in observed hand actions. Eur J Pain. 2015;19(9):1372-81.

- ↑ Packham T, MacDermid JC, Henry J, Bain J. A systematic review of psychometric evaluations of outcome assessments for complex regional pain syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(13):1059-69.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 PENTLAND, B. Parkinsonism and dystonia. By: Greenwood R, McMillan T, Barnes M, Ward C. (eds) Handbook of Neurological Rehabilitation. 1st ed. London: Psychology Press, 2002.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Sebastin SJ. Complex regional pain syndrome. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011 May;44(2):298-307.

- ↑ Rommel O, Malin JP, Zenz M, Jänig W. Quantitative sensory testing, neurophysiological and psychological examination in patients with complex regional pain syndrome and hemisensory deficits. Pain. 2001 Sep;93(3):279-93.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 Frontera W, Silver J. Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation - Musculoskeletal disorders, Pain and Rehabilitation. Saunders Elsevier, 2002.

- ↑ Arizona Pain. Stellate Ganglion Block. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=izOYrLUuNd8 [ accessed 7/7/23]

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Lee BH, Scharff L, Sethna NF, McCarthy CF, Scott-Sutherland J, Shea AM, Sullivan P, Meier P, Zurakowski D, Masek BJ, Berde CB. Physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral treatment for complex regional pain syndromes. J Pediatr. 2002 Jul;141(1):135-40.

- ↑ Daly AE, Bialocerkowski AE. Does evidence support physiotherapy management of adult Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type One? A systematic review. European Journal of Pain. 2009 Apr 1;13(4):339-53.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 McCabe CS, Haigh RC, Blake DR. Mirror visual feedback for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome (type 1). Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008 Apr;12(2):103-7.

- ↑ Somers D, Clemente F. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for the Management of Neuropathic Pain: The Effects of Frequency and Electrode Position on Prevention of Allodynia in a Rat Model of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type II. Phys Ther. 2006;86(5):698-709.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Collins CK. Physical therapy management of complex regional pain syndrome I in a 14-year-old patient using strain counterstrain: a case report. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15(1):25-41.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Stanton-Hicks M, Baron R, Boas R, Gordh T, Harden N, Hendler N, Koltzenburg M, Raj P, Wilder R. Complex Regional Pain Syndromes: guidelines for therapy. Clin J Pain. 1998 Jun;14(2):155-66.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 Smith TO. How effective is physiotherapy in the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome type I? A review of the literature. Musculoskeletal Care. 2005;3(4):181-200.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Bowering KJ, O'Connell NE, Tabor A, Catley MJ, Leake HB, Moseley GL, Stanton TR. The effects of graded motor imagery and its components on chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2013 Jan;14(1):3-13.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Moseley GL. Graded motor imagery is effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2004 Mar;108(1-2):192-8.

- ↑ Oaklander AL, Rissmiller JG, Gelman LB, Zheng L, Chang Y, Gott R. Evidence of focal small-fiber axonal degeneration in complex regional pain syndrome-I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). Pain. 2006 Feb;120(3):235-43.

- ↑ Kemler MA, De Vet HC, Barendse GA, Van Den Wildenberg FA, Van Kleef M. The effect of spinal cord stimulation in patients with chronic reflex sympathetic dystrophy: two years' follow-up of the randomized controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2004 Jan;55(1):13-8.

- ↑ Devrimsel G, Turkyilmaz AK, Yildirim M, Serdaroglu Beyazal M. The effects of whirlpool bath and neuromuscular electrical stimulation on complex regional pain syndrome. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015 Jan; 27(1): 27–30.

- ↑ Anandkumar S, Manivasagam M. Multimodal physical therapy management of a 48-year-old female with post-stroke complex regional pain syndrome. Physiother Theory Pract. 2014 Jan;30(1):38-48.