Chondromalacia Patellae

Original Editors - Francky Petit

Top Contributors - Francky Petit, Gianni Delmoitie, Scott Cornish, Admin, Kim Jackson, Ine Van de Weghe, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Scott Buxton, George Prudden, Robbe Luyckx, Sem Bras, Tessa Fransis, 127.0.0.1, Nupur Smit Shah, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk and Naomi O'Reilly

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Chondromalacia patellae (CMP) is referred as anterior knee pain due to the physical and biomechanical changes [1]. It manifests as a softening, swelling, fraying, and erosion of the hyaline cartilage underlying the patella and sclerosis of underlying bone [2] which means that the articular cartilage of the posterior surface of the patella is going though degenerative changes [3].

Chondromalacia patellae is one of the most frequently encountered causes of anterior knee pain among young people. It’s the number one cause in the United States with an incidence as high as one in four people.[51] The word chondromalacia is derived from the Greek words chrondros, meaning cartilage and malakia, meaning softening. Hence chondromalacia patellae is a softening of the articular cartilage on the posterior surface of the patella which may eventually lead to fibrillation, fissuring and erosion.[40]

CMP is one of the main conditions under the blanket term, Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) [1][4] and is also known as Runner’s Knee.[5]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy [edit | edit source]

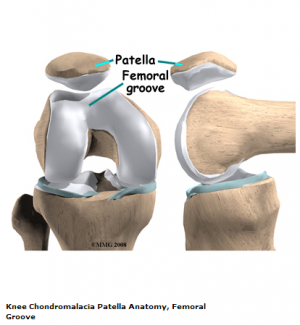

The knee comprises of 4 major bones: the femur, tibia, fibula and the patella. The patella articulates with the femur at the trochlear groove. [6] Articular cartilage on the underside of the patella allows the patella to glide over the femoral groove, necessary for efficient motion at the knee joint. [7] Excess and persistent turning forces on the lateral side of the knee can have a negative effect on the nutrition of the articular cartilage and more specifically in the medial and central area of the patella, where degenerative change will occur more readily. [8]

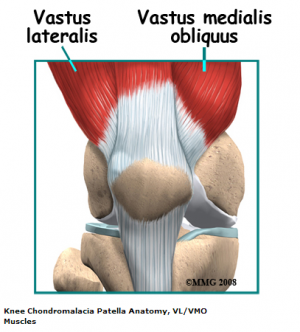

The quadriceps insert into the patella via the quadriceps tendon and is divided into four different muscles: rectus femoris (RF), vastus lateralis (VL), vastus intermedius (VI) and vastus medialis (VM). The VM has oblique fibres which are referred to the vastus medialis obliques (VMO)[9]

These muscles are active stabilisers during knee extension, especially the VL (on the lateral side) and the VMO (on the medial side). The VMO is active during knee extension but does not extend the knee. Its function is to keep the patella centred in the trochlea. This muscle is the only active stabiliser on the medial aspect, so it's functional timing and amount of activity is critical to patellofemoral movement, the smallest change having significant effects on the position of the patella.

Not only the quadriceps will influence the patella position, but also the passive structures. “The passive structures are more extensive and stronger on the lateral side than they are on the medial side, with most of the lateral retinaculum arising from the iliotibial band (ITB). If the ITB is tight, excessive lateral tracing and/ or lateral patellar tilt can occur.” This is most likely as a result of tensor fasciae lata being teight, as the ITB itself is unable to be stretched considerably due to its structure [8].

Other anatomical structures we should pay attention to, are:

- The femoral anteversion [10]: or medial torsion of the femur is a condition which changes the alignment of the bones at the knee. This may lead to overuse injuries of the knee caused by malalignment of the femur in relation to the patella and tibia. [11]

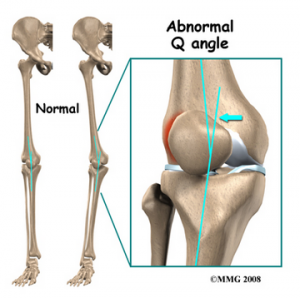

- The Q-angle: or 'quadriceps angle' can be defined as the geometric relationship between the pelvis, the tibia, the patella and the femur. [11] [12]

If there is an increased adduction and/or internal rotation of the hip, the Q angle will increase. When the Q angle is increased, the relative valgus of the lower extremity will increase as well. The increased Q angle and valgus will increase the contact pressure on the lateral side of the patellofemoral joint. Also, patellofemoral contact pressure is increased by external rotation of the tibia. [45]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The etiology of CMP is poorly understood, although most authorities believe that the causes of chondromalacia are injury, generalized constitutional disturbance and patellofemoral contact[13], or a result of trauma to the chondrocytes in the articular cartilage (leading to proteolytic enzymatic digestion of the superficial matrix). Some authorities believe that chondromalacia is caused by instability or maltracking of the patella that softens the articular cartilage. [14](1B) Chondromalacia patella is usually described as an overload injury (overuse, misuse), caused by malalignment of the femur to the patella and the tibia. [15]

Main reasons for patellar malalignment

- Q-angle : An abnormality of the Q-angle is one of the most important factors of Patellar malalignment. A normal Q-angle is 14° for men and 17° for women. An increase in Q-angle can result in increased lateral pull of the patella.

- Muscle tightness :

- Rectus femoris: if this muscle is tight, it will affect the patellar movement during flexion of the knee.

- Iliotibial band: if tight, it will pull the patella to the lateral side during knee flexion.

- Hamstrings: if this muscle is tight during running it will increase knee flexion which results in increased ankle dorsiflexion. This causes compensatory pronation in the talocrural joint.

- Gastrocnemius: if tight, it will result in compensatory pronation in subtalar joint.

- Excessive pronation: prolonged pronation of the subtalar joint is caused by internal rotation of the leg. This internal rotation will result in malalignment of the patella.

- Patella alta : this is the situation where the patella is positioned to high for normal standards. it is present when the length of the patellar tendon is 20% greater than the height of the patella.

- Vastus medialis insufficiency: the function of the vastus medialis is to realign the patella during knee extension. If the strength of the vastus medialis is insufficient it will cause a lateral drift of the patella.[49]

Sometimes, a muscular imbalance between the VL en VM lies underneath. Weakness of the VM causes the patella to be pulled too far laterally. The patella will grind onto the condylus lateralis, which causes the degenerative disease.[16]

Degenerative changes of the articular cartilage can be caused by [17]:

- Trauma: instability caused by a previous trauma or misuse during recovery

- Repetitive micro trauma and inflammatory conditions

- Postural distortion: causes malposition or dislocation of the patella in the trochlear groove

Studies prove that hip positioning and strength are linked to the prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Therefore, hip strengthening and coordination exercises may be useful in the treatment program of patellofemoral pain syndrome. [45]

Some authors will use the term “patellar pain syndrome” instead of “chondromalacia” in order to describe “anterior knee pain”. [18]

Stages of disease

In an early stage, chondromalacia shows areas of high sensitivity on fluid sequences. This can be associated with the increased thickness of the cartilage and may also cause oedema. In a later stage, there will be a more irregular surface with focal thinning that can expand to and expose the subchondral bone. [19]

Chondromalacia patella is graded based on the basis of arthroscopic findings, the depth of cartilage thinning and associated subchondral bone changes. MRI is able to visualize this condition for moderate to severe forms. [20]

- Stage 1: softening and swelling of the articular cartilage due to broken vertical collagenous fibres. The cartilage is spongy on arthroscopy.

- Stage 2: blister formation in the articular cartilage due to the separation of the superficial from the deep cartilaginous layers. Cartilaginous fissures affecting less than 1,3 cm2 in area with no extension to the subchondral bone.

- Stage 3: fissures ulceration, fragmentation, and fibrillation of cartilage extending to the subchondral bone but affecting less than 50% of the patellar articular surface.

- Stage 4: crater formation and eburnation of the exposed subchondral bone more than 50% of the patellar articular surface exposed, with sclerosis and erosions of the subchondral bone. Osteophyte formation also occurs at this stage.

Articular cartilage does not have any nerve endings, thus the CMP should not be considered as the true source of anterior knee pain. Actually chondromalacia is a pathological or surgical finding that represents areas of articular cartilage trauma or divergent loading. [7]

In 2013, a retrospective review showed that there is significant association between subcutaneous knee fat thickness with the presence and severity of chondromalacia patellae. This could explain why women suffer more from the condition chondromalacia than men (Kok et al;, 2013). [21]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

There are important distinguishing features between chondromalacia patellae and Osteoarthritis. But chondromalacia patellae affects just one side of the joint, the convex patellar side. [22] Excised patellas show localized softening and degeneration of the articular cartilage. [23]The main symptom of chondromalacia patellae is anterior knee pain.[13] The pain is exacerbated by common daily activities that load the patellofemoral joint, such as running, stair climbing, squatting, kneeling[1], or changing from a sitting to a standing position [24]. The pain often causes disability which affects short term participation as daily and physical activities.[25] Other symptoms are tenderness when you palpate under the medial or lateral border of the patella [26]; crepitation, this may be demonstrated with motion [27](B); minor swelling [26]; a weak vastus medialis muscle, and a high Q-angle [28]. The vastus medialis is functionally divided into two components: the vastus medialis longus (VML) and the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO). The VML extends the knee, with the rest of the quadriceps muscle. The VMO doesn’t extend the knee, but this muscle is also active throughout the knee extension. This component keeps the patella centered in the trochlea of the femur. [8] The Q-angle is defined as the angle between the first line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the center of the patella and the second line from the center of the patella to the tibial tuberosity [29](3B).

This condition fits within the general category of PFP [26] also causes a deficit in strength of the quadriceps muscle. Therefore, quadriceps strengthening exercises is often part of the revalidation plan.[1] A significant number of individuals are asymptomatic, but crepitation in flexion or extension is mostly present. [30] Chondromalacia is common by adolescents and females. Idiopathic chondromalacia is mostly seen by young children and adolescents. Degenerative chondromalacia is common by middle-aged people and old age population. [19]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Patellar subluxation

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Anterior knee pain

- Patellofemoral pain syndrome

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Since its first description bij Budinger in 1906, chondromalacia patella has been a great clinical interest, because diagnosis is often difficult. The chief reason for this is that the aetiologie is not known and the correlation between the articular cartilage changes and the clinical system is poor. The patients affected bij chondromalacia patella are young, between 15 and 35 years old, and many are athletic. Often they are considerably disabled by the symptoms of aching behind the patella, recurrent effusion of the knee, instability of the knee and crepitus.[57]

The primary diagnostic approach for chondromalacia patellae is radiography with added arthrography. Pinhole scintigraphy is a part of arthrography that can be used to diagnose chondromalacia patellae. [43]

MRI is also a very good way to diagnose Chondromalacia patellae. It’s a non-invasive method and it is easily performed. There is a possibility to increase the strength of the magnets and mount a specialized coil which increase sensitivity and specificity of the diagnose.[53]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are different measurements: [55],[56]

- The Anterior Knee Pain Scale : This is a 13-item questionnaire with discrete categories related to various levels of current knee function. Categories within each item are weighted, and responses are summed to provide an overall index in which 100 represents no disability.

- Visual analog scales : Three 10-cm visual analog scales, the start of the 10cm line indicates no experience of pain, while the end indicates the worst pain imaginable for the patient. The patient can indicate how much pain is experienced by marking it on the scale.

- The five KOOS subscales : Is a scale to measure the opinion of patients with knee problems that can result in post traumatic osteoarthritis and is measured over time. It consist of five subscales Pain, other Symptoms, Function in daily living, Function in sport and recreation and knee related Quality of life.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Examination of the knee may be divided into four categories -look, move, feel, X-ray.[40]

I. Look - the joint appearance is usually normal but occasionally there may be a slight effusion.

2. Move - passive movements are usually full and painless but repeated extension of the knee from flexion will produce pain and grating under the patella especially if the articular surfaces are pressed together.

3. Feel (i) Pain and crepitus will be felt if the patella is rubbed against the femur, either vertically or horizontally, with the knee in full extension. (ii) By displacing the patella medially or laterally, the patellar margins and their articular surfaces may be felt. Tenderness of one or other margin may be elicited.. It is more frequently the medial one.. (iii) Resistance of a static quadriceps contraction, by placing the hand proximal to the upper border of the patella, will produce a sharp pain under the patella. This may be apparent in both knees but more severe on the affected side.

4. X-ray - a skyline view of the patellofemoral joint is needed to detect any radiological change. In all, hut the most advanced cases, there is no convincing radiological change. In the later stages, the patellofemoral joint space narrows and still later osteoarthritic changes appear.

Tests

First of all the hardest task for the physiotherapist is to ascertain the disease. At first it is necessary to inspect the position and posture of the patient. Look at eventual asymmetries, like the limb alignment in standing, internal femoral rotation, anterior or posterior pelvic tilt, hyperextended or ‘locked back’ knees, genu varum or valgum and abnormal pronation of the foot. When there are asymmetries or abnormal positions in one of these anatomic structures, it will affect the patient's gait pattern. [9]

Next you have to test the mobility / range of motion (ROM) of the joint. With chondromalacia there is very often a limitation in the ROM. When there is a bursitis present, a passive flexion or active extension will be painful. You can also test the isometric power of the muscles, here especially the quadriceps. The affected leg will show a loss of power, according to the non-injured leg. There are also some specific test to diagnose anterior knee pain syndrome, of which CMP is a part: [33]

- Patellar-grind test a.k.a. Clarke’s sign : The purpose of this test is to detect the presence of patellofemoral joint disorder. Patient is positioned in supine or long sitting with the involved knee extended. The examiner places the web space of his hand just superior to the patella while applying pressure. The patient is instructed to gently and gradually contract the quadriceps muscle. A positive sign on this test is pain in the patellofemoral joint. (http://www.physio-pedia.com/Patellar_Grind_Test )

- Compression test

- Extension-resistance test : The extension resistance test is used to perform a maximal provocation on the muscle-tendon mechanism of the extensor muscles. The extension resistance test is positive when the affected knee shows less power to hold the pressure. If positive we can say the extensor mechanism of the knee is disturbed. The patient is instructed to perform an extension of the knee joint, while the therapist exercises pressure in the opposite direction (flexion). The therapist evenly builds up his pressure, the patient is to allow no movement in the joint. Resistance tests should be performed on both knees and compared to one another. (http://www.physio-pedia.com/Knee_Extension_Resistance_Test)

- The critical test: This test is done with the patient in high sitting. The patient must do isometric quadriceps contractions in 5 different angles (0°, 30°, 60°, 90° and 120°) while the femur is externally rotated. The contraction must be sustained for 10 seconds. If pain is produced by the isometric contractions, then the leg has to be brought into full extension. In this position the patella and femur have no more contact. The lower leg of the patient is supported by the therapist so the quadriceps can be fully relaxed. When the quadriceps is relaxed, the therapist is able to glide the patella medially. This glide is maintained while the isometric contractions are performed again. If this reduces the pain and the pain is patellofemoral in origin, there is a higher chance in a favourable outcome.[51]

Note that it is still possible to diagnose incorrectly, these test may help in determine chondromalacia but it is best to rule out other diagnoses. [5]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Exercise and education are two very important parts of therapy. The education should help the patient to understand the problem and how he should deal with it for an optimal recovery. The exercises should be focused on stretching and strengthening the knee. Stretching of the hamstring, iliotibial band, quadriceps and gastrocnemius are the most important. Strengthening exercises of the gluteal muscle.[58] (level1) It is also proven that fire needling and acupuncture in high stress points could relieve clinical symptoms of chondromalacia patellae and recovers the biodynamicall structure of patellae. [50] (level 1A)

If conservative measures fail, though, there are a number of possible surgical procedures. These procedures take place when the symptoms remain the same after the conservative measures. [20]

The first option is called shaving, also known as chondrectomy. This treatment includes shaving down the damaged cartilage, just to the not-damaged cartilage underneath. The success of this treatment depends on the severity of the cartilage damage.

Drilling is also a method that is frequently used to heal the damaged cartilage. However, this procedure has not so far been proved to be effective. More localized degeneration might respond better to drilling small holes through the damaged cartilage. This facilitates the growth of the healthy tissue through the holes, from the layers underneath.

The most severe surgical treatment is a full patellectomy. This operation is only used when no other procedures were helpful. A big consequence is that the quadriceps will weaken very hard. Two potential treatments may be successful: [17]

- Replacement of the damaged cartilage : The damaged cartilage is replaced by a polyethylene cap prosthesis. Early results have been good, but eventual wearing of the opposing articular surface is inevitable.

- Autologous chondrocyte transplantation under a tibial periosteal patch. [17]

Simply removing the cartilage is not enough to cure chondromalacia patellae. The biomechanical problem needs addressing and there are various procedures to aid re-alignment :

1. Thightening of the medial capsule (MC) : If the MC is lax, it can be tightened by pulling the patella back into its correct alignment.

2. Lateral release : A very tight lateral capsule will pull the patella laterally. Release of the lateral patellar retinaculum allows the patella to track correctly into the femoral groove.

3. Medial shift of the tibial tubercle : Moving the insertion of the quadriceps tendon medially at the tibial tubercle, allows the quadriceps to pull the patella more directly. It decreases also the amount of wear on the underside of the patella.

4.Removal of a portion of the patella

Although there is no agreement of the treatment of chondromalacia, there is a general consensus that the best treatment is a non-surgical one.[31]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Exercise Program

Conservative treatment of chondromalacia patellae is both physical and advisory.

Short-wave diathermy helps to relieve pain and increase the blood supply to the area, so improving the nutrition to the articular cartilage. Care must be taken when planning the exercise programme. [40] ( level 3 )

The most common way to treat chondromalacia patellae is by strengthening the quadriceps muscle, because it has a very significant role in the movement of the patella.[1] The best way to do this is with isometric quadriceps exercises and isotonic exercises in inner range. Isotonic quadriceps exercises through full range will only lead to increased pain and even joint effusion.[40](level3) Stretching of the vastus lateralis and strengthening of the vastus medialis is often recommended, but they are difficult to isolate because they have the same innervation and insertion.[9][16] Therefore, it’s easier to strengthen the whole quadriceps.

Since the positioning and strength of the hip has a significant influence on anterior knee pain, training its strength and coordination is recommended. An increased hip adduction angle is associated with weakened hip abductors, so strengthening the hip abductors is advised. [45](Level 1A)

Many cases of chondromalacia patellae are self-limiting and treatment is primarily nonsurgical. Conservative therapeutic interventions include the following: [52]( level 5)

- Isometric quadriceps strengthening and stretching exercises – restoration of good quadriceps strength and function is an important factor in achieving good recovery.

- Hamstring stretching exercises

- Temporary modification of activity

- Patellar taping

- Foot orthoses

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

In this aspect of the therapy, make sure to give strength exercises, resistance exercises and coordination exercises of the quadriceps. Here is an example of an exercise program[32]:

Coordination Exercises

- Sit with the IL on a rolled towel under the fossa popliteum with no weight on the leg. Extend the leg fast an relax slowly 50x

- stand on one leg (IL) with the knee slightly bent. Tap the foot of the HL in front, left, right and behind you on the floor

- Jumping: from left to right, from the back to the front, in a square and in a diamond.

- By increasing the depth of a squat exercise progressively, the activity of the M. Gluteus Medius will increase. Thus, adding single-leg squats on a physioball to the program, lower extremity coordination and hip position in relation to the knee, may improve. Perform single-leg squats with a physioball between a wall and your back. the focus with this activity should be proper knee and hip positioning. [45](Level 1A)

- Manual perturbations applied against the hip musculature in side lying with one leg raised. [45] (Level 1A)

- Performing a lunge with a twist. Perform a lunge while twisting your torso with your hands raised in front of you.[45] (Level 1A)

Strength Exercises

- Extend the IL for 10 seconds.

- Strengthening the hip abductors begins with isometric exercises, performing prone heel squeezes will positively affect muscle recruitment of the hip abductors. [45] (Level 1A)

Resistance Exercises

- sit at the front of a chair with both legs extended just above the floor. Push the heel of the healthy leg(HL) against the heel of the injured leg(IL). Make sure there is no movement in both legs. Hold for 7 seconds.

- Sit with the IL on a rolled towel under the fossa popliteum, with a weight on the leg

- Stand with the IL, slightly bent, in front of the extended HL. Bend the IL slowly. Make sure the knee never passes the foot. Move your weight to the IL. When you feel pain, quit immediately.

- stand with the IL on a step. Touch with the HL the floor by bending the IL, first with the toes, then with the foot, then with the heel of the foot.

- Standing abduction with a resistance band. [45] (Level 1A)

- Side-to-side walking with a resistance band. [45] (Level 1A)

Not only do you have to strengthen the quadriceps, stretching is also important. And hereby you can also stretch the hamstrings and the iliotibial band. [7] It is proven that patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome have shorter hamstrings than asymptomatic controls. Also are their hamstrings less flexible. It is recommended to stretch this tissues because it seems to improve the flexibility and knee function. Though it doesn’t improve pain or function by stretching alone. Including stretching in the therapy, in addition to active treatments, gives positive outcomes. [33]

Ice & Drugs

Ice is sure to decrease pain, but is more frequently used to treat acute injuries. The efficacy of ice is questioned and the exact effect isn’t clear too. Therefore, more studies are required to create evidence based guidelines.[16][34]

The benefit of anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s) has not yet been proved. Although a lot of treatments for CMP aren’t proved either, the potential side effects of NSAID’s may be more severe than the side effects of ice and exercise. Therefore, a judicious trail may be worthwile[16].

Tapes and braces

Taping the patella into a certain position may be helpful, but the scientific evidence is varied. A commonly used technique is the ‘McConnell taping’. When taped properly, the McConnell tape may have a short-term pain relief.[16][35][36]

Every form of supporting the patella and knee joint has proven that it can possibly reduce pain and symptoms but it is also possible it will change the tracking of the patella. Though it can be helpful because during the rehabilitation, patients will avoid certain movements to reduce the pain. This can cause a less functioning of the quadriceps. So using a brace or every form of support, that relieves the patient from pain, may aid in the recovery, as they will dare to use their quadriceps. This can be used for patients preoperatively as well as postoperatively. However there is suggested to use a brace which allows variation in the medial patellar pull and pressure. [18]

Foot Orthoses

Foot orthoses may be helpful in the pain relief of the knee, but only if the patient has signs of an excessive foot pronation, or a lower extremity alignment profile that includes excessive lower extremity internal rotation during weight bearing and increased Q-angle at the same time as he suffers from chondromalacia. When made properly, the orthotics will cause biomechanical changes (for example: a reduction in the Q-angle and internal rotation) in the lower leg by preventing overpronation in pes planus and providing a better support for normal feet and Pes cavus.[25][16] [18]

Other

Using a foam roller could also be considered due to its pain relieving effect. Running on an injury will leave you with tight and stiff muscles, which a foam roller and some quad stretching can loosen up. Just take care not to stretch if it irritates your knee.[54]

Key Research [edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

http://www.tlichtpuntje.be/info/patellaafwijkingen.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chondromalacia_patellae

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Patellar_Grind_Test

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Knee_Extension_Resistance_Test

http://www.medicinenet.com/patellofemoral_syndrome/article.htm

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1RQQ955bivekjtuIeEbqjzR1uasP0NSfaxOzigsJzEwDNhsISG: Error parsing XML for RSS

Read for Credit

|

Would you like to earn certification to prove your knowledge on this topic? All you need to do is pass the quiz relating to this page in the Physiopedia member area. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Lee Herrington and Abdullah Al-Sherhi, A Controlled Trial of Weight-Bearing Versus Non–Weight-Bearing Exercises for Patellofemoral Pain, journal of orthopaedic sports physical therapy, 2007, 37(4), 155-160

- ↑ Gagliardi et al., Detection and Staging of Chondromalacia Patellae: Relative Efficacies of Conventional MR Imaging, MR Arthrography, and CT Arthrography, ARJ, 1994, 163, 629-636

- ↑ http://www.e-radiography.net/radpath/c/chondromalaciap.htm

- ↑ http://www.ubsportsmed.buffalo.edu/education/patfem.html

- ↑ http://orthopedics.about.com/cs/patelladisorders/a/chondromalacia.htm

- ↑ http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1898986-overview#aw2aab6b3 fckLR(Levels of Evidence: 5E)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 ANDERSON M. K. ,Fundamentals of Sports Injury Management, second edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003, p. 208 (Levels of Evidence: 5F)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 BEETON K. S., Manual Therapy Masterclasses, The Peripheral Joints, Churchill Livingstone, 2003, p.50-51 fckLR(Levels of Evidence: 5E)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Florence Peterson Kendall et al., Spieren : tests en functies, Bohn Stafleu van Loghum, Nederland, 469p (383)

- ↑ NYLAND J et al., Femoral anteversion influences vastus medialis and gluteus medius EMG amplitude: composite hip abductor EMG amplitude ratios during isometric combined hip abduction-external rotation, Elsevier, vol. 14, issue 2, April 2004, p. 255-261. (Levels of Evidence: 2C)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 MILNER C. E., Functional Anatomy For Sport And Exercise: Quick Reference, Routledge, 2008, p. 58-60 fckLR(Levels of evidence: 5E)

- ↑ SINGH V., Clinical And Surgical Anatomy, second edition, Elsevier, 2007, p. 228- 230. fckLR(Levels of Evidence: 2C)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Iraj Salehi, Shabnam Khazaeli, Parta Hatami, Mahdi Malekpour, Bone density in patients with chondromalacia patella, Springer-Verlag, 2009

- ↑ MACMULL S., The role of autologous chondrocyte implantation in the treatment of symptomatic chondromalacia patellae, International orthopaedics, Jul 2012, 36(7), 1371-1377. (Levels of Evidence: 1B)

- ↑ BARTLETT R., Encyclopedia of International Sports Studies, Routledge, 2010, p. 90. (Levels of Evidence: 5F)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 http://www.aafp.org/afp/991101ap/2012.htm

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 LOGAN A. L., The Knee Clinical Applications, Aspen Publishers, 1994, p. 131. (Levels of Evidence: 5F)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 MANSKE R. C., Postsurgical Orthopedic Sports Rehabilitation: Knee & Shoulder, 2006, Mosby Elsevier, p. 446, 451. (Levels of Evidence: 5E)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 WESSELY M., YOUNG M., Essential Musculoskeletal MRI: A Primer for the Clinician, Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2011, p. 115. (Levels of Evidence: 5E

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 MUNK P. L., RYAN A. G., Teaching Atlas of Musculoskeletal Imaging, Thieme, 2008, p. 68-70. (Levels of Evidence: 5E)

- ↑ KOK HK., Correlation between subcutaneous knee fat thickness and chondromalacia patellae on magnetic resonance imaging of the knee, Canadian Association of Radiologists journal, Aug 2013, 64(3), 182-186. (Levels of Evidence: 2B)

- ↑ ELLIS H., FRENCH H., KINIRONS M. T., French’s Index of differential diagnosis, 14th edition, Hodder Arnold Publishers, 2005. (Levels of Evidence: E)

- ↑ ANDERSON J. R., Muir’s Textbook of Pathology, 12th edition, Lippincott Williams Wilkins, 1988 (Levels of Evidence: C)

- ↑ MOECKEL E., NOORI M., Textbook of Pediatric Osteopathy, Elsevier Health Sciences 2008, p. 338. (Levels of Evidence: D)

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bill Vicenzino, Natalie Collins, Kay Crossley, Elaine Beller, Ross Darnell and Thomas McPoil, fckLRFoot orthoses and physiotherapy in the treatment of patellofemoralfckLRpain syndrome: A randomised clinical trial, BioMed Central, 2008

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 SHULTZ S. J., HOUGLUM P. A., PERRIN D. H., Examination of Musculoskeletal injuries, third edition, Human Kinetics, 2010, p. 453. (Levels of Evidence: E)

- ↑ DEGOWIN R. L., DEGOWIN E. L., DeGowin & DeGowin’s Diagnostic Examination, 6th edition, McGraw Hill, 1994, p. 735. (Levels of Evidence: B)

- ↑ EBNEZAR J., Textbook of Orthopedics¸ 4th edition, JP Medical Ltd, 2010, p. 426-427. (Levels of Evidence: E)

- ↑ ASSLEN M. et al., The Q-angle and its Effect on Active Joint Kinematics – a Simulation Study, Biomed Tech 2013; 58 (suppl 1). (Levels of Evidence: 3B)

- ↑ MURRAY R. O., JACOBSON H. G., The Radiology of Skeletal Disorders: exercises in diagnosis, second edition, Churchill Livingstone, 1990, p. 306-307. (Levels of Evidence: E)

- ↑ R van Linschoten et al., Supervised exercise therapy versus usual care for patellofemoral pain syndrome: an open label randomised controlled trial, BMJ, 2009

- ↑ P. van der Tas J.M. Klomp-Jacobs; Chondropathie Patellae; Maatschap voor Sport-Fysiotherapie, Manuele Therapie en Medische Trainings Therapie

- ↑ HARVIE D. et al., A systematic review of randomized controlled trials on exercise parameters in the treatment of patellofemoral pain: what works?, J. Multidiscip Healthc. 2011, vol. 4, p. 383 – 392. (Levels of Evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Bleakley C, McDonough S, MacAuley D. The use of ice in the treatment of acute soft-tissue injury: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sport Med. 2004; 32:251-261

- ↑ Derasari A. et al.;McConnell taping shifts the patella inferiorly in patients with patellofemoral pain: a dynamic magnetic resonance imaging study; Journal of the American Physical Therapy association; 2010 March; 90(3): 411–419

- ↑ Naoko Aminaka Phillip A Gribble; A Systematic Review of the Effects of Therapeutic Taping on Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome; Journal of Athletic Training; 2005 Oct–Dec; 40(4): 341–351

39. McConnell, Jenny. "The management of chondromalacia patellae: a long term solution." Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 32.4 (1986): 215-223.

40. Helen M. Gordon : CHONDROMALACIA PATELLAE1 1Delivered at the XV Biennial Congress of the Australian Physiotherapy Association, Hobart, February 1977. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, Volume 23, Issue 3, September 1977, Pages 103-106

41. Wibeeg, Gunnar. "Roentgenographs and anatomic studies on the femoropatellar joint: with special reference to chondromalacia patellae." Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica 12.1-4 (1941): 319-410.

42. Bentley, George. "The surgical treatment of chondromalacia patellae." Bone & Joint Journal 60.1 (1978): 74-81.

43. Bahk YW, Park YH, Chung SK, Kim SH, Shinn KS. “Pinhole scintigraphic sign of chondromalacia patellae in older subjects: a prospective assessment with differential diagnosis.” Journal of Nuclear Medicine : Official Publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine [1994, 35(5):855-862]

44. Calmbach, Walter L., and Mark Hutchens. "Evaluation of patients presenting with knee pain." Part II. Am Physician 68 (2003): 917-22.

45. Erik P. Meira, Jason Brumitt. “Influence of the Hip on Patients With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review.” Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, September/October 2011; vol. 3, 5: pp. 455-465. (Level of Evidence: 1A)

46. KE Marks, G Bentley. “patella alta and chondromalacia.” Bone & Joint Journal, vol. 60-B, no. 1, p71-73.

47. Marcus A. Rottermich, Neal R. Glaviano, Jiacheng Li, Joe M. Hart. “Patellofemoral pain.” Clin Sports Med 34 (2015), p313-327.

48. Eugene Hong, Michael C. Kraft. “Evaluating Anterior Knee Pain.” Med Clin N Am 98 (2014), p697-717.

49. Jenny McConnell. “The management of chondromalacia patellae: a long term solution.” Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, volume 32, issue 4, 1986, pages 215-223.

50. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2014 Jun;34(6):551-4. [Efficacy observation on chrondromalacia patellae treated with fire needling technique at high stress points]

51. Laprade J, Culham E, Brouwer B (1998) Comparison of five isometric exercises in the recruitment of the vastus medialis oblique in persons with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 27: 197–204

52. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/384485/chondromalacia_patellae.pdf

53. Kim, H. J., Lee, S. H., Kang, C. H., Ryu, J. A., Shin, M. J., Cho, K. J., & Cho, W. S. (2011). Evaluation of the chondromalacia patella using a microscopy coil: comparison of the two-dimensional fast spin echo techniques and the threedimensional fast field echo techniques. Korean J Radiol, 12(1), 78-88. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.1.78

54. Davis, John. "Runner’s Knee: Symptoms, Causes and Research-Backed Treatment Solutions for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome."

55. Petersen, Wolf, et al. "Evaluating the potential synergistic benefit of a realignment brace on patients receiving exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized clinical trial." Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery (2016): 1-8.

56. Crossley, Kay M., et al. "Analysis of outcome measures for persons with patellofemoral pain: which are reliable and valid?." Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 85.5 (2004): 815-822.

57. George Bentley, Ian J. Lesly and David Fischer. “Effect of aspirin treatment on chondromalacia patella” Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 1981, 40, p37-41.

58. CLARK, D. I., N. DOWNING, J. MITCHELL, L. COULSON, E. P. SYZPRYT, and M. DOHERTY. Physiotherapy for anterior knee pain: a randomised controlled trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59:700–704, 2000.