Knee Osteoarthritis

Original Editors - Fien Selderslaghs, Laura Van Der Perren, Mirabella Smolders, Liese Magnus

Top Contributors - Mirabella Smolders, Laura Van Der Perren, Hamelryck Sascha, Abbey Wright, Laura Ritchie, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Jessica Davis, Fien Selderslaghs, Rachael Lowe, Bo Hellinckx, Venugopal Pawar, Admin, Vidya Acharya, Ophélie Schraepen, 127.0.0.1, Feebe Robyns, Joni Roesems, Candace Goh, Barb Clemes, Jess Bell, Kai A. Sigel, Sai Kripa, WikiSysop, Aminat Abolade, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Robin Tacchetti, Rishika Babburu, Arthur Devoldere, Jelien Wouters, Evan Thomas, Anthony Mertens, Rucha Gadgil and Michelle Lee

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Knee osteoarthritis (OA), also known as degenerative joint disease, is typically the result of wear and tear and progressive loss of articular cartilage. It is most common in elderly people and can be divided into two types, primary and secondary:

- Primary osteoarthritis - is articular degeneration without any apparent underlying cause.

- Secondary osteoarthritis - is the consequence of either an abnormal concentration of force across the joint as with post-traumatic causes or abnormal articular cartilage, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Osteoarthritis is a painful, chronic joint disorder that primarily affects not only the knees but also hands, hips and spine. The intensity of the symptoms vary for each individual and usually progress slowly.

Common clinical symptoms include

- Knee pain that is gradual in onset and worsens with activity

- Knee stiffness and swelling

- Pain after prolonged sitting or resting

- Crepitus or a cracking sound with joint movement

Treatment for knee osteoarthritis begins with conservative methods and progresses to surgical treatment options when conservative treatment fails. While medications can help slow the progression of RA and other inflammatory conditions, there are currently no proven disease-modifying agents for the treatment of knee OA.[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

OA is the most common disease of the joints worldwide, with the knee being the most commonly affected joint in the body. [3] It mainly affects people over the age of 45.

OA can lead to pain and loss of function, but not everyone with radiographic findings of knee OA will be symptomatic: in one study only 15% of patients with radiographic findings of knee OA were symptomatic[1][3].

- OA affects nearly 6% of all adults

- Women are more commonly affected than men[3]

- Roughly 13% of women and 10% of men 60 years and older have symptomatic knee osteoarthritis.[1]

- Among those older than 70 years of age, the prevalence rises to as high as 40%.[1]

- Prevalence will continue to increase as life expectancy and obesity rises.[4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Knee OA is classified as either primary or secondary, depending on its cause[3]:

- Primary knee OA is the result of articular cartilage degeneration without any known reason. This is typically thought of as degeneration due to age as well as wear and tear.

- Secondary knee OA is the result of articular cartilage degeneration due to a known reason. Possible Causes of Secondary Knee OA:

- Obesity

- Joint hypermobility or instability

- Malpositioning of the joint e.g. valgus/varus posture

- Previous injury to the joint e.g. fracture along articular surface (tibial plateau fracture)

- Congenital defects

- Immobilisation and loss of mobility

- Family history

- Metabolic causes e.g. rickets

Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The knee (art. genus) is a synovial joint, which consists of 2 articulations.

- Tibiofemoral joint is located between the convex femoral condyles and the concave tibial condyles (the primary joint).[5]

- Patellofemoral joint between the Femur and the Patella

OA can occur in either or both of these articulations of the knee, it is usual that the patellofemoral joint is affected first.[6]

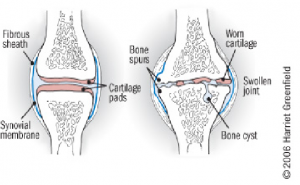

Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

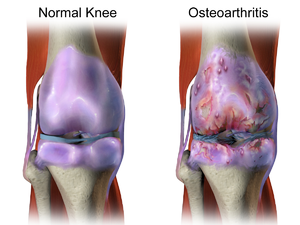

The process of osteoarthritis affects the articular cartilage (mainly type II) that covers the articular surfaces of bone[1].

Articular cartilage is normally maintained in a healthy equilibrium of chemical reactions, however, when OA starts to develop the reactions are disrupted leading to changes in the collagen of the cartilage[7][8]:

- Disruption in the equilibrium which results in the disorganised pattern of collagen, and loss of articular cartilage elasticity.

- This results in cracking and fissuring of the cartilage which leads to erosion of the articular surface.[1]

- Cartilage that has been damaged, cannot recover.

- The cartilage will continue to wear away

- Once the cartilage has worn away; bony surfaces will start to be affected

- The bone will expand and spurs (osteophytes) will develop.

It is common for ligament laxity and muscle atrophy to also occur as the disease progresses. [9]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs of knee OA are:

- Pain upon movement

- Stiffness, particularly early morning stiffness

- Loss of range of movement

- Pain after prolonged sitting or lying

- Pain on joint line palpation

- Joint enlargement.[10]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

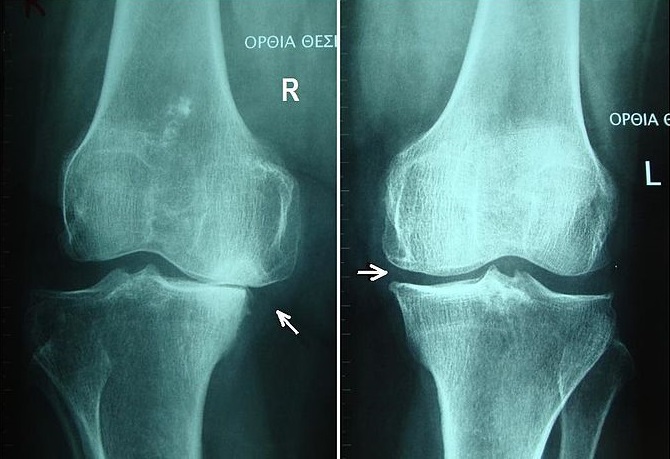

The diagnosis can be established by clinical examination, and it can be confirmed by X-rays.

Knee OA can be sub-divided into 5 grades:

- Grade 0: This is the “normal” knee health

- Grade 1: Very minor bone spur growth and is not experiencing any pain or discomfort.

- Grade 2: This is the stage where people will experience symptoms for the first time. They will have pain after a long day of walking and will sense a greater stiffness in the joint. It is a mild stage of the condition, but X-rays will already reveal greater bone spur growth. The cartilage will likely remain at a healthy size.

- Grade 3: Moderate OA. Frequent pain during movement, joint stiffness will also be more present, especially after sitting for long periods and in the morning. The cartilage between the bones shows obvious damage, and the space between the bones is getting smaller.

- Grade 4: This is the most severe stage of OA. The joint space between the bones will be dramatically reduced, the cartilage will almost be completely gone and the synovial fluid will be decreased. This stage is normally associated with high levels pain and discomfort during walking or moving the joint.[11]

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

Blood Tests; to help determine the type of arthritis

Physical examination: see below

X-ray: A basic X-ray is used to research breakdown of cartilage, narrowing of joint space, forming of bone spurs and to exclude other causes of pain in the affected joint.

Arthrocentesis: This is a procedure which can be performed at the doctor’s office. A sterile needle is used to take samples of joint fluid which can then be examined for cartilage fragments, infection or gout.

Arthroscopy: is a surgical technique where a camera is inserted in the affected joint to obtain visual information about the damage caused to the joint by the OA.

MRI. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Provides a view that offers better images of cartilage and other structures to detect early abnormalities typical of osteoarthritis[12].

Radiographic Findings of OA[edit | edit source]

- Joint space narrowing

- Osteophyte formation

- Subchondral sclerosis

- Subchondral cysts[1]

- Early stages of OA shows a minimal unequal joint space narrowing.

- In severe OA the joint line may disappear completely (see image 2).[10]

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment for knee OA can be broken down into conservative and surgical management.

Initial treatment always begins with conservative modalities and moves to surgical treatment once conservative management has been exhausted. There is a wide range of conservative modalities available for the treatment of knee OA.

The main focus in OA management is on promoting self-management, reducing pain, optimise function, and modifying the disease process and its effects.[13]

Conservative Treatment Options[edit | edit source]

The primary treatment for OA knee conservatively is exercise therapy within physiotherapy.[14] Physiotherapy normally involves

- Patient education

- Exercise therapy

- Activity modification

- Advice on weight loss

- Knee bracing

- The first-line treatment for all patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis includes patient education and physiotherapy. A combination of supervised exercises and a home exercise program have been shown to have the best results. These benefits are lost after 6 months if the exercises are stopped.[14]

- Weight loss is valuable in all stages of knee OA. It is indicated in patients with symptomatic OA with a body mass index greater than 25. The best recommendation to achieve weight loss is with diet control and low-impact aerobic exercise.

- Knee bracing in OA can be used. Offloading-type braces which shift the load away from the involved knee compartment. This can be effective when there is a valgus or varus deformity.

Other non-physiotherapy based interventions include pharmacological management[1]:

- Acetaminophen

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- COX-2 inhibitors

- Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate

- Corticosteroid injections

- Hyaluronic acid (HA)

- Drug therapy alongside physiotherapy should be the first-line treatment for patients with symptomatic OA. There are a wide variety of NSAIDs available, however, caution should be used when prescribing NSAIDs due to their side effects.[15]

- Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are available as dietary supplements. They are structural components of articular cartilage, and the thought is that a supplement will aid in the health of articular cartilage. No strong evidence exists that these supplements are beneficial in knee OA.

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections may be useful for symptomatic knee OA.

- Intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections (HA) injections are another inject-able option. Local delivery of HA into the joint acts as a lubricant and may help increase the natural production of HA in the joint.

Differential Diagnosis[1][edit | edit source]

- Meniscal pathology

- Patellofemoral pain syndrome

- Gout and Pseudogout

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Septic arthritis[16]

- Hip OA

- Referred lower back pain

- Ligament injury ACL or PCL rupture

Examination[edit | edit source]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Take a proper history of pain including when the pain started if it was gradual or sudden, if there was any previous injury to the same knee.

The common subjective symptoms of knee OA are:

- Early morning stiffness

- Dull achy pain

- Pain after sitting

- Pain after increased activity

- Reduced mobility

- Difficulty weight bearing on the affected leg

- Decrease in the abilities of daily functioning

- Sleep may be affected (screen red flags appropriately)

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

After a thorough subjective assessment it may be clear the diagnosis of the patient already, however, it is always necessary to perform an objective assessment to rule out differential diagnoses and provide objective outcome measures such as range of movement (ROM).

- Observation of the knee: it may be enlarged, swollen or red if the OA is very reactive or irritated.

- Observation in general: movement patterns at rest and when performing simulations of daily activities such as getting up from and down on a chair

- Gait assessment: use of walking aids may be required due to pain, is there any stiffness during gait, is there significant reduced weight bearing of the affected knee.

- Palpation: swelling, temperature changes, joint line tenderness may all be present in an acutely aggravated OA knee

- ROM: flexion and extension may be limited due to stiffness or formation of osteophytes in the joint

- Strength: reduced strength is normal in an OA knee due to pain and deconditioning

- Normal functional activities: such as climbing stairs may be affected

- Balance: may be affected due to pain, this needs to be assessed to rule out falls risk.

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy should be started with all patients with a diagnosis of OA[17].

Pain is a common symptom that occurs at different intensities depending on the individual, it is not necessarily related to severity of OA progression[18].

Exercise has been proven to be effective as pain management and also improves physical functioning in the short term.[10][19] Exercises have to take place under the supervision of a physiotherapist initially and when properly instructed these exercises can be performed at home, though research has shown that group exercise combined with home exercise is more effective.[20]

Role of Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Education[edit | edit source]

- Understanding what OA is

- Explaining pain

- Explain long term management of OA

- Educate regarding activity modification

- Role of weight loss

- Promote active, healthy lifestyle

Exercise[edit | edit source]

- Reduces knee pain and inflammation.

- Normalises knee joint range of motion.

- Strengthens lower kinetic chain

- Reduces risk of cardiovascular disease

- Improves proprioception, agility and balance.

- Promotes physical function

Land-based exercises are ideal for most people and are strongly recommended.[21] Aquatic exercise, stationary cycling, and walking are safe and effective activities that do not cause undue stress on the knee joint.[13]

Exercise has also been found to be beneficial for other co-morbidities and overall health. Walking, resistance training, cycling, yoga and Tai Chi are examples of such exercises. An individualised exercise program should be set by a physiotherapist initially, taking into account the patient's goals and hobbies to ensure long term exercise compliance.

Movement or physical activity is the best medicine for people suffering from knee osteoarthritis. Performing physical activity may not only improve your joint mobility, it can also improve your overall quality of life and can help reduce depression.[13] Individuals with knee OA commonly engage in strengthening their knee muscles, neglecting however hip muscle strengthening. On assessing patients with knee OA they would usually be presented with hip muscle weakness and are more prone to increase in medial compartment loading on the knee joint. Research has proven that patients with knee pain will benefit following hip strengthening exercises. Potential benefits includes quick pain relief and better hip strength. It is important to strengthen the hip in knee OA because hip strengthening exercises tend to improve the mechanics of your lower limb and reduce stress on the knee.[22]

A new systematic review published in the journal Rheumatology Advances in Practice aiming to evaluate factors related to fatigue in individuals with hip and or knee OA found out that there is strong or moderate evidence that high numbers of co-morbidities or illness burden and modifiable factors, such as high depressive symptoms, low levels of self-reported physical function, high pain and low physical activity levels, are associated with greater fatigue, making these factors possible targets for fatigue reduction in hip and/or knee OA populations. The review showed there was moderate evidence of no association between sociodemographic factors (age, education, race, living situation or circumstances), BMI, radiographic OA severity and fatigue; and conflicting evidence for the association between poor performance-based physical function, high anxiety, high joint stiffness, poor sleep and low social support with higher fatigue.[23]

The video below gives 5 home exercises for people with knee OA.

Other Interventions[edit | edit source]

There are various forms of therapeutic interventions that may or may not be helpful for patients with various degrees of evidence to support them:

- Hydrotherapy - this may be particularly helpful if pain is very high and analgesia is not tolerated. It can be useful to build up strength and reduce stiffness around the knee joint in a non-weight bearing position.[25] [26]

- Taping - works to offload the joint similar to bracing, this is useful in the short term. A systematic review shows elastic taping leads to no significant change in WOMAC score for improvement of pain in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis and alternative conservative treatments to elastic taping should be explored if OA knee pain persists for more than 21 days.[27]

- Manual therapy - effective to improve ROM[28]According to a systematic review, manual therapy (mobilisation with movement, passive joint mobilisation, patellar mobilisation therapy ) and exercises effectively reduce knee pain and increase functionality. However, further research is needed to determine the long-term effects of manual therapy on knee OA.[29]

- Massage - may be useful to control pain in some subjects, but this has low evidence to show its effectiveness[30]

- Bracing

- Electrotherapy -such as muscle stimulation to improve quadricep strength and TENS as it has some evidence to show it can help with pain reduction [31]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

If conservative management is not sufficient at controlling pain, surgical interventions can be explored.The most common forms of surgery for this condition are (from least to most invasive):

- Therapeutic Injections

- Arthroscopy - with the goal to remove osteophytes and any degenerative meniscal tears (this should not be considered if no osteophytes are present on XR)[32]

- High tibial Osteotomy - if the patient meets the pre-operative functional level

- Patellofemoral joint arthroplasty - if only the patellofemoral joint is affected, and tibiofemoral joints are healthy

- Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty - if only one compartment (medial or lateral) is affected

- Total knee replacements

The below video gives a good guide to both surgical and non surgical options and why or when they are offered.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Knee OA is best managed initially by conservative management. Failing this intervention and with positive radiographic evidence of OA surgical options can be considered to reduce pain in the long term and improve quality of life.

- OA has no cure and thus attempts should be made to prevent progression of the disease.

- Treatment for knee OA begins with conservative methods and progresses to surgical treatment options when conservative treatment fails.

- A multi-disciplinary team approach should be taken to promote healthy lifestyle and control pain i.e. physiotherapist, dietitian and pharmacist

- Orthopaedic specialists should be referred to if pain becomes unmanageable.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Verses Arthritis - patient resources, also offers free handouts for healthcare professionals

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Hsu H, Siwiec RM. Knee Osteoarthritis.2019 Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507884/ (last accessed 28.2.2020)

- ↑ rBioventus Stages of knee OA Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBqjltHNOrc&feature=youtu.be (last accessed 17.11.2019)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Michael JW, Schlüter-Brust KU, Eysel P. The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 2010 Mar;107(9):152.

- ↑ Cui A, Li H, Wang D, Zhong J, Chen Y, Lu H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Dec 1;29:100587.

- ↑ Jennifer Reft. Knee Osteokinematics and Arthokinematics. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EyhiCvWER0Y [last accessed 07/12/2014]

- ↑ Brukner P, Clarsen B, et al. Brukner & Khan's Clinical sports medicine 5th edition. McGraw Hill Education; 2017; p777

- ↑ Buckwalter JA, Mankin HJ, Grodzinsky AJ. Articular cartilage and osteoarthritis. Instructional Course Lectures-American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;54:465.

- ↑ Pearle AD, Warren RF, Rodeo SA. Basic science of articular cartilage and osteoarthritis. Clinics in sports medicine. 2005 Jan 1;24(1):1-2.

- ↑ E. Schulte, et al., General anatomy and musculoskeletal system, Atlas of Anatomy, 2006: 372-373

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 RK Arya, Vijay Jain, Osteoarthritis of the knee joint: An overview, Journal Indian Academy of Clinical Medicine, 2013, 14(2): 154-62

- ↑ Lespasio MJ, Piuzzi NS, Husni ME, Muschler GF, Guarino AJ, Mont MA. Knee osteoarthritis: a primer. The Permanente Journal. 2017;21.

- ↑ Osteoarthritis Diagnosis Arthritis Foundation Available from: https://www.arthritis.org/about-arthritis/types/osteoarthritis/diagnosing.php (last accessed 17.11.2019)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Schlenk EA, Xiaojun Shi BS. Evidence based practices for osteoarthritis management. American Nurse Today 2019;14.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Collins NJ, Hart HF, Mills KA. Osteoarthritis year in review 2018: rehabilitation and outcomes. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2019 Mar 1;27(3):378-91.

- ↑ Aweid O, Haider Z, Saed A, Kalairajah Y. Treatment modalities for hip and knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review of safety. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2018 Nov 8;26(3):2309499018808669.

- ↑ E. RINGDAHL, et al., Treatment of Osteoarthritis, American Family Physician, 2011, 83(11):1287-1292.

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Management of osteoarthritis [internet]. [London]: NICE 2019 [updated 2020, cited May 2020] (NICE pathways). Available from: https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/osteoarthritis#path=view%3A/pathways/osteoarthritis/management-of-osteoarthritis.xml&content=view-node%3Anodes-core-treatments-information-exercise-and-weight-loss

- ↑ M. Elboim-Gabyzon, N. Rozen, and Y. Laufer. Gender Differences in Pain Perception and Functional Ability in Subjects with Knee Osteoarthritis. ISRN Orthopedics. Volume 2012, Article ID 413105, 4 pages

- ↑ McAlindon TE, Bannuru R, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Hawker GA, Henrotin Y, Hunter DJ, Kawaguchi H, Kwoh K. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2014 Mar 1;22(3):363-88.

- ↑ McCarthy CJ, Mills PM, Pullen R, Richardson G, Hawkins N, Roberts CR, Silman AJ, Oldham JA. Supplementation of a home-based exercise programme with a class-based programme for people with osteoarthritis of the knees: a randomised controlled trial and health economic analysis. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 2004;8:2015.

- ↑ RACGP Guidelines for hip and knee arthritis Available from: https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Musculoskeletal/guideline-for-the-management-of-knee-and-hip-oa-2nd-edition.pdf (last accessed 18.11.2019)

- ↑ Neelapala YR, Bhagat M, Shah P. Hip Muscle Strengthening for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review of Literature. Journal of geriatric physical therapy. 2020 Apr 1;43(2):89-98.[1]

- ↑ Fawole HO, Idowu OA, Abaraogu UO, Dell’Isola A, Riskowski JL, Oke KI, Adeniyi AF, Mbada CE, Steultjens MP, Chastin SF. Factors associated with fatigue in hip and/or knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Rheumatology advances in practice. 2021;5(1):rkab013.

- ↑ Good exercise guide. 10 Best Exercises for Knee Arthritis, Full Physio Sequence. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=syBi8gw4dsA [last accessed 14/09/2014]

- ↑ Silva LE, Valim V, Pessanha AP, Oliveira LM, Myamoto S, Jones A, Natour J. Hydrotherapy versus conventional land-based exercise for the management of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Physical therapy. 2008 Jan 1;88(1):12-21.

- ↑ Hinman RS, Heywood SE, Day AR. Aquatic physical therapy for hip and knee osteoarthritis: results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Physical therapy. 2007 Jan 1;87(1):32-43.

- ↑ Heddon S, Saulnier N, Mercado J, Shalmiyev M, Berteau JP. Systematic review shows no strong evidence regarding the use of elastic taping for pain improvement in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis. Medicine. 2021 Apr 2;100(13).

- ↑ Deyle GD, Allison SC, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Stang JM, Gohdes DD, Hutton JP, Henderson NE, Garber MB. Physical therapy treatment effectiveness for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized comparison of supervised clinical exercise and manual therapy procedures versus a home exercise program. Physical therapy. 2005 Dec 1;85(12):1301-17.

- ↑ Tsokanos A, Livieratou E, Billis E, Tsekoura M, Tatsios P, Tsepis E, Fousekis K. The Efficacy of Manual Therapy in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Medicina. 2021 Jul;57(7):696.

- ↑ Perlman AI, Sabina A, Williams AL, Njike VY, Katz DL. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006 Dec 11;166(22):2533-8.

- ↑ Mascarin NC, Vancini RL, dos Santos Andrade M, de Paiva Magalhães E, de Lira CA, Coimbra IB. Effects of kinesiotherapy, ultrasound and electrotherapy in management of bilateral knee osteoarthritis: prospective clinical trial. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2012 Dec 1;13(1):182.

- ↑ National institute for health and care excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis: care and management [internet]. [London]. NICE; 2008. [updated 2014 Feb, cited May 2020], Clinical guideline [CG177] Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177/chapter/1-Recommendations#referral-for-consideration-of-joint-surgery-2

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Mayo Clinic's Approach to Knee Arthritis - Both Surgical and Non-Surgical Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Mk9GZ7-Dz8 (last accessed 17.11.2019)