Cervical Stenosis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Evan Thomas (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 189: | Line 189: | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

1) M.J. Lee et Al., Prevalence of Cervical Spine Stenosis, The journal of bone and joint surgery, 2007.<sup>[1]Level of Evidence 2C</sup><br>2) M. McDonnell et Al., Cervical Spondylosis, stenosis, and Rheumatoid Arthritis, Medicine & Health/Rhode Island, Vol.95, No.4, April 2012. <sup>[2]Level of Evidence 5</sup><br>3) L.Yang et Al., Plate-only Open-door Laminoplast Versus Laminectomy and Fusion fort he Treatment of Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy, Healio Orthopedics, Vol. 36, January 20132.<sup>[3]Level of Evidence 2B</sup><br>4) H. Chikuda et Al., Optimal treatment for Spinal Cord Injury associated with Cervical canal Stenosis( OSCIS): a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial comparing early verus delayed surgery, BioMed Central, 2013.<sup>[4]Level of Evidence 1B</sup><br>5) K.Yeh et Al., Expansive open-door laminoplasty secured with titanium miniplates is a good surgical method for multiple-level cervical stenosi, Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, August 2014.<sup>[5]Level of Evidence 2B</sup><br>6) May, S. & Comer, C. Is surgery more effective than non-surgical treatment for spinal stenosis, and which non-surgical treatment is more effective? A systematic review. Physiotherapy, 2013, 99(1), 12-20. <sup>(Level of Evidence 1A)</sup><br>7) Atlas SJ, Delitto A. Spinal stenosis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 443:198. <sup>(level of evidence: 5)</sup><br>8) Hu SS, et al. Cervical spondylosis section of Disorders, diseases, and injuries of the spine. In HB Skinner, ed., Current Diagnosis and Treatment in Orthopedics, 4th ed., pp. 238–242. New York: McGraw-Hill.,2006 <sup>(level of evidence: 5)</sup><br>9) Li X, Li J, Wu X. “Incidence, risk factors and treatment of cervical stenosis after radical trachelectomy: A systematic review.” European Journal of Cancer (2015) Sep;51(13):1751-9. <sup>LoE: 1A</sup><br>10) Desai SK, et al. “Isolated cervical spinal canal stenosis at C-1 in the pediatric population and in Williams syndrome.” J Neurosurg Spine. 2013 Jun;18(6):558-63. LoE: <br>11) Aboulker J, Metzger J, David M., Engel P., Ballivet J. (1965) Les myèlopathies cervicales d’origine rachidienne. Neurochirurgie 11: 89-198. LoE:<br>12) Payne E., Spillane J. (1957) The cervical spine. An Anatomicopathological study of 70 specimens (using a special technique) with particular reference to the problem of cervical spondylosis. Brain 80: 571. LoE:<br>13) João Levy M., António Fernandes F., João Lobo A. “Neurologic aspects of systemic disease part I.” Handbook of clinical neurology: Chapter 35- Spinal Stenosis (2014) Volume 119; pg 541-549.<sup>LoE:5</sup><br>14) Denaro V. “Stenosis of the cervical spine: causes, diagnosis, treatment” (1991) Springer- verlag Berlin Heidelberg. Pg. 6-26. <sup>LoE: 5</sup><br>15) Boni M, Denaro V. “The cervical stenosis syndrome.” Int Ortho (1982) p:185-195. LoE: <br>16) Hashizume Y, Lijima S, Kishimoto H, et al. “Pathology of spinal cord lesions caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament.” (1984) Acta neuropathol (Berlin) 63: 123-130. <br>17) Y. Yukawa et Al., Laminoplasty and Skip Laminoplasty for Cervical Compressive Myelopathy, Spine, 2007.<sup>[17]Level of Evidence 2B</sup | 1) M.J. Lee et Al., Prevalence of Cervical Spine Stenosis, The journal of bone and joint surgery, 2007.<sup>[1]Level of Evidence 2C</sup><br>2) M. McDonnell et Al., Cervical Spondylosis, stenosis, and Rheumatoid Arthritis, Medicine & Health/Rhode Island, Vol.95, No.4, April 2012. <sup>[2]Level of Evidence 5</sup><br>3) L.Yang et Al., Plate-only Open-door Laminoplast Versus Laminectomy and Fusion fort he Treatment of Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy, Healio Orthopedics, Vol. 36, January 20132.<sup>[3]Level of Evidence 2B</sup><br>4) H. Chikuda et Al., Optimal treatment for Spinal Cord Injury associated with Cervical canal Stenosis( OSCIS): a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial comparing early verus delayed surgery, BioMed Central, 2013.<sup>[4]Level of Evidence 1B</sup><br>5) K.Yeh et Al., Expansive open-door laminoplasty secured with titanium miniplates is a good surgical method for multiple-level cervical stenosi, Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, August 2014.<sup>[5]Level of Evidence 2B</sup><br>6) May, S. & Comer, C. Is surgery more effective than non-surgical treatment for spinal stenosis, and which non-surgical treatment is more effective? A systematic review. Physiotherapy, 2013, 99(1), 12-20. <sup>(Level of Evidence 1A)</sup><br>7) Atlas SJ, Delitto A. Spinal stenosis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 443:198. <sup>(level of evidence: 5)</sup><br>8) Hu SS, et al. Cervical spondylosis section of Disorders, diseases, and injuries of the spine. In HB Skinner, ed., Current Diagnosis and Treatment in Orthopedics, 4th ed., pp. 238–242. New York: McGraw-Hill.,2006 <sup>(level of evidence: 5)</sup><br>9) Li X, Li J, Wu X. “Incidence, risk factors and treatment of cervical stenosis after radical trachelectomy: A systematic review.” European Journal of Cancer (2015) Sep;51(13):1751-9. <sup>LoE: 1A</sup><br>10) Desai SK, et al. “Isolated cervical spinal canal stenosis at C-1 in the pediatric population and in Williams syndrome.” J Neurosurg Spine. 2013 Jun;18(6):558-63. LoE: <br>11) Aboulker J, Metzger J, David M., Engel P., Ballivet J. (1965) Les myèlopathies cervicales d’origine rachidienne. Neurochirurgie 11: 89-198. LoE:<br>12) Payne E., Spillane J. (1957) The cervical spine. An Anatomicopathological study of 70 specimens (using a special technique) with particular reference to the problem of cervical spondylosis. Brain 80: 571. LoE:<br>13) João Levy M., António Fernandes F., João Lobo A. “Neurologic aspects of systemic disease part I.” Handbook of clinical neurology: Chapter 35- Spinal Stenosis (2014) Volume 119; pg 541-549.<sup>LoE:5</sup><br>14) Denaro V. “Stenosis of the cervical spine: causes, diagnosis, treatment” (1991) Springer- verlag Berlin Heidelberg. Pg. 6-26. <sup>LoE: 5</sup><br>15) Boni M, Denaro V. “The cervical stenosis syndrome.” Int Ortho (1982) p:185-195. LoE: <br>16) Hashizume Y, Lijima S, Kishimoto H, et al. “Pathology of spinal cord lesions caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament.” (1984) Acta neuropathol (Berlin) 63: 123-130. <br>17) Y. Yukawa et Al., Laminoplasty and Skip Laminoplasty for Cervical Compressive Myelopathy, Spine, 2007.<sup>[17]Level of Evidence 2B</sup><br> | ||

[[Category:Conditions]] [[Category:Cervical Spine]] [[Category:Cervical_Conditions]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | |||

[[Category: | |||

Revision as of 10:40, 10 October 2016

Original Editors - Demol Yves as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Demol Yves, Rachael Lowe, Sara Evenepoel, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, Admin, Daphne Jackson, David Herteleer, Nicolas Casier, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Rucha Gadgil, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Tony Lowe and Evan Thomas

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Cervical stenosis is defined by the narrowing of the vertebral canal, which may result in a compression on the spinal cord and/or the nerve roots. Especially narrowing of the sagittal diameter of the cervical spinal canal is of clinical importance in traumatic, degenerative and inflammatory conditions. Because of this narrowing, the function of the spinal cord or the nerve may be affected, which may cause symptoms associated with cervical radiculopathy or cervical myelopathy. Spinal stenosis, or narrowing of the spinal canal, may occur as a result of progression of spondylotic changes. [1]Level of Evidence 2C, [2]Level of Evidence 5

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The cervical vertebrae starts just below the skull and ends just above the thoracic spine. It has a lordotic curve. The cervical spine is much more mobile than both of the other spinal regions and its purpose is to contain and protect the spinal cord, support the skull, and enable diverse head movements. (7,8 level of evidence: 5)

It is the smallest of the vertebrae, in comparison with the other spinal vertebrae. The cervical vertebrae consists of the first seven vertebrae in the spine characterized by a large and triangular vertebral foramen and small foramina in the transverse processes (except C7) that allow vertebral arteries, veins and nerves to pass through The atlas is the first cervical vertebra, the one that sits between the skull and the rest of spine. The atlas does not have a vertebral body, but does have a thick anterior arch and a thin posterior arch, with two prominent sideways masses.

The atlas sits on top of the second cervical vertebra, the axis. The axis has a bony knob called the odontoid process that sticks up through the hole in the atlas. It is this special arrangement that allows the head to turn from side to side as far as it can. Special ligaments between these two vertebrae allow a great deal of rotation to occur between the two bones. The atlas and the axis, differ from the other vertebrae because they are designed specifically for rotation. These two vertebrae are what allow your neck to rotate in so many directions. (7,8 level of evidence: 5)

The ligaments of the cervical vertebrae guide the intra-articular movements in the most optimal directions in order to avoid cartilage damage and muscle hypertonicity. They also prevent excessive movements, which could otherwise lead to serious injuries. The ligamentum flavum is a broad, fibrous ligament that connects the laminae of adjacent vertebral arches. The elastic nature of the ligament helps to maintain the natural curvature of the spinal column and protects the intervertebral discs.

The following muscles act on the cervical spine and help to maintain its balance and stability:

- Longus capitis

- Longus colli

- Spinalis cervicis

- Semispinalis capitis

There is also a group of muscles that acts to ensure that the head can move in all directions:

Though its flexibility, the cervical spine is very much at risk for injury from strong, sudden movements, for example whiplash-type injuries. The high risk is due to: the limited muscle support in the area, and because it has to support the weight of the head which is a lot for a small, thin set of bones and soft tissues to bear.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Cervical Stenosis:

- Epidemiological data give an incidence of 1:100 000 cervical spine stenosis cases

- Is a major postoperative complication after radical trachelectomy (abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic) [9] LoE 1A

- Is a potential cause of infertility [9] LoE: 1 A

- Isolated cervical spinal canal stenosis at the level of C1 is a rare cause of cervical myelopathy [10]

- Space between the meningoneural structures in the canal to the size of the canal= consequence of stenosis. LoE: [11]

- When there is enough space in the canal for other tissue, maybe there won’t be a pathological change. But when there is a constricted canal, the probability of a pathology is larger.

- Cervical spine stenosis most commonly causes cervical myelopathy in 50+ aged patients [13]

Stenosis of the cervical canal= better understand area within the cervical segment of the spinal column.

A spinal stenosis is in fact a reduced perimeningeal space.

Definition:

Clinical situations affecting:

1. Cervical spinal cord

2. Cervical nerve roots

--> Surgical dilatation (resolved stenosis in the majority but it had to be repeated) [9] - LoE 1A

Cervical stenosis can be defined as 1. Functional stenosis or 2. Organic stenosis.

- Functional Stenoses [14]

(There will be a kinetic change. The stenosis causes a change in function, physiological and or biomechanical.)

- Degenerative pseudospondylollisthesis with arthrosis

- Mild post-traumatic laxity

- Ligamentous laxity

- kinetic overload of a segment

- loss of appropriate lordosis

- …

2. Organic Stenoses

(There will be a morphological and/ or anatomical change. The stenoses can be classified into congenital and more frequently, acquired stenoses.)

Classification of symptomatic spinal narrowing (organic stenosis): [13]

A. Congenital [13, 14]

(idiopathic)

o Malformations involving severe morphological deformity of the canal in the occipitocervical plane

o Malformations without serious structural distortion of the cervical canal

o Stenoses which result from systemic congenital disease which become manifest during growth and development.

o …

B. Acquired [15]

There are multiple etiological factors:[14] LoE:5

o Degenerative processes

o Destructive processes

o Traumatic processes

o Arthritic conditions

o Iatrogenic causes

- Degenerative stenosis

Spinal arthrosis (degenerative disk disease)

- Destructive stenosis

Stenosis associated with neoplasm

- Inflammatory stenosis

- Traumatic stenosis

This clinical situation is a result of a trauma to the cervical spine.

It can progress to an imbalance between the cord and the cervical spinal canal.

- Iatrogenic stenosis

= cervical stenosis as a complication of surgery in the neck or/and spine.

-> Instability resulting from extensive laminectomy

-> Peridural postoperative fibrosis

-> …

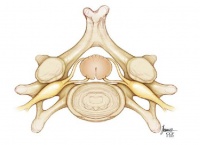

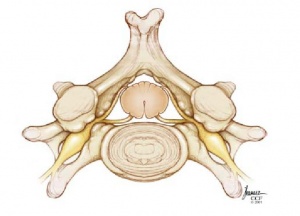

Cervical stenosis typically has an insidious onset. The condition is characterized by a narrowing of the spinal canal, nerve root canal, or foramen. Pathological changes to a range of tissues in the region could be at fault. Examples include soft tissue damage (such as disc protrusion or fibrotic scars), boney tissue damage (such as osteophyte formation or spondylolisthesis), or impaired postural mechanics. Narrowing of the canal causes compression of the spinal cord and nerves at the effected level, leading to neurological symptoms as the condition progresses.[1]

Left picture: www.physio-pedia.com/File:Normal-cervical.jpg Right picture: www.physio-pedia.com/File:Cervica-Stenosis.jpg

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Cervical stenosis does not necessarily cause symptoms, but if symptoms are present they will mainly be caused by associated cervical radiculopathy or cervical myelopathy.

Potential symptoms may include:Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

- Pain in neck or arms

- Arm and leg dysfunction

- Weakness, stiffness or clumsiness in the hands

- Leg weakness

- Difficulty walking

- Frequent falling

- The need to use a cane or walker

- Urinary urgency which may progress to bladder and bowel incontinence

- Diminished proprioception

The progression of the symptoms may also vary:

- A slow and steady decline

- Progression to a certain point and stabilizing

- Rapidly declining

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acute cervical disc herniation

- Cervical vertebral compression fracture

- Cervical spine facet syndrome

- Osteoarthritis of intervertebral joints in cervical spine

- Cervical spondylotic myelopathy [8]Level of evidence 5 [2]Level of evidence 5

- Osteophytes

- Buckled, thickened, or ossified ligamentum flavum

- Hypertrophy or ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[3]Level of Evidence 2B [17] Level of evidence 2B

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Physical examination: Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

- Hyper-reflexia: Increased reflexes in the knee and ankle

- Changes in gait, such as clumsiness or loss of balance

- Loss of sensitivity in the hands or feet

- Rapid foot beating that is triggered by turning the ankle upward

- Babinski’s sign

- Hoffman’s sign

X-rays of the cervical spine do not provide enough information to confirm cervical stenosis, but can be used to rule out other conditions. Cervical stenosis can occur at one level or multiple levels of the spine, therefore an MRI is useful for looking at several levels at one time. A detailed MRI image may also be useful to show the tight spinal canal and pinching of the spinal cord. A CT scan can provide information about the bony invasion of the canal and can be combined with myelography. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- CT and MRI

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can give a better image and understanding of the cervical spine. Specific and accurate measurements of the canal are important. CT and MRI is used for much better visualization. Space between the meningoneural structures in the canal to the size of the canal= consequence of stenosis. [11, 12]

These techniques make it possible to study the canal in three dimensions, the diameter, volume, the peringeal space and the state of the cord (morphometric features) without biopsy or sampling. [11]

With the CT, classification of acquired stenoses will be based on the pattern of protusion of the calcification of the ligament into the spinal canal. [16]

- It is difficult to identify this pathology with physical examination. [13]

See Outcome Measures Database for more

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

For patients presenting with increasing weakness, pain or instability with walking, surgical management of cervical spine stenosis may be considered.

Options for decompressing multilevel stenosis involve:

Anterior approaches:

- Anterior cervical discectomy with fusion

- Anterior cervical corpectomy with fusion

- Combination of both[3]Level of Evidence 2B

The disc or bone material( or both) that are causing spinal cord compression are removed from the anterior aspect and the spine is stabilized. The stabilizing of the spine, which is called fusion, involves placing an implant between the two cervical segments to support the spine and compensate for the bone and the disc that has been removed.

Posterior approaches:

- Laminectomy without fusion or with instrumented fusion: This is a procedure where the bone and ligaments that are pressing against the spinal cord are removed. In this treatment the surgeon might add also a fusion to stabilize the spine.[3]Level of Evidence 2B

- Laminoplasty [3] Level of Evidence 2B[5]Level of Evidence 2B

The posterior approach relies on the decompression by both the direct removal of offending posterior structures and indirect posterior translation of the spinal cord; thus, patients should undergo maintenance of lordosis or correctable kyphosis to permit adequate indirect decompression.

The distinction between these two types operations, depends on the location of the cord compression, number of levels involved, sagittal alignment, instability, associated axial neck pain, and risk factors for pseudarthrosis.

Laminoplasty is more effective to laminectomy without fusion because it decreases perineural adhesion and late kyphosis. The anterior techniques as well as the laminectomy with fusion are less effective than the laminoplasty. The laminoplasty preserves motion segments and prevents fusion-related complications, including bone graft dislodgement, pseudarthrosis, and adjacent segment disease. [3]Level of Evidence 2B, [4]Level of Evidence 1B

After the surgery, the patient has to remain in the hospital for several days. A postoperative rehabilitation program may be provided, so that the patient can return to his activities and his typical daily function. This program consisted of an early post-operative ROM exercise, with or without a neck-collar. [17]Level of Evidence 2B

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Nonoperative treatments, such as physical therapy management, are aimed at reducing pain and increasing the patient's function. Nonoperative treatments do not change the narrowing of the spinal canal, but can provide the patient of a long-lasting pain control and improved function without surgery. A rehabilitation program may require 3 or more months of supervised treatment. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The purpose of physical therapy is to decrease pain and allow you to. Non-operative treatments, such as physical therapy management, are aimed at reducing pain and increasing the patient's functioning by gradually returning to normal activities Non-operative treatments do not change the narrowing of the spinal canal but may reduce pain in the soft tissues (such as the muscles, ligaments, and tendons), improve function, and build muscle strength. but can provide the patient of a long-lasting pain control and improved function without surgery. A rehabilitation program may require 3 or more months of supervised treatment. Non-surgical treatement involves physical or mechanical means, such as through exercise or heat. A physical therapist provides these treatments and will also provide education, instruction, and support for recovery. 6 Level of Evidence 1A ,7,8 level of evidence: 5

A physical therapy program may include:

• Stretching exercises: These exercises are aimed at restoring the flexibility of the muscles of the neck, trunk, arms and legs. To also reduce stress on joints

• Manual therapy: Cervical and thoracic joint manipulation to improve or keep range of motion

• Heat therapy : to improve blood circulation to the muscles and other soft tissues.

• Cryotherapy : to help relieve pain

• Cardiovascular exercises for arms and legs: This will improve blood circulation and enhance the patient's cardiovascular endurance and promote good physical conditioning

• Aquatic exercises: to allow your body to exercise without pressure on the spine

• Training of activity of daily living (ADL) and functional movements.

Exercises and techniques that may help relieve symptoms of spinal stenosis and prevent progression of the condition include:6 Level of Evidence 1A,7,8 level of evidence: 5

• Specific strengthening exercises for the arm, trunk and leg muscles.

• stretching

• Postural re-education

• Scapular stabilization

• Ergonomics and frequent changes of position, to avoid sustained postures that compress the spine

• Planning ahead so that you take breaks in between potentially back-stressing activities such as walking and yard work.

• Proper lifting, pushing, and pulling.

P.S. some of the exercises are similar to the other forms of spinal stenose such as lumbale stenosis : lumbar spinal stenose

www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_spinal_stenosis

Key Research

[edit | edit source]

- L.Yang et Al., Plate-only Open-door Laminoplast Versus Laminectomy and Fusion fort he Treatment of Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy, Healio Orthopedics, Vol. 36, January 20132.Level of Evidence 2B

Recourses

[edit | edit source]

- H. Chikuda et Al., Optimal treatment for Spinal Cord Injury associated with Cervical canal Stenosis( OSCIS): a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial comparing early verus delayed surgery, BioMed Central, 2013.[4]Level of Evidence 1B

- May, S. & Comer, C. Is surgery more effective than non-surgical treatment for spinal stenosis, and which non-surgical treatment is more effective? A systematic review. Physiotherapy, 2013, 99(1), 12-20. (Level of Evidence 1A)

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

[edit | edit source]

- The morphological and clinical significance of developmental cervical stenosis. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25813007?dopt=Abstract)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques. 6th ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, 2012.

1) M.J. Lee et Al., Prevalence of Cervical Spine Stenosis, The journal of bone and joint surgery, 2007.[1]Level of Evidence 2C

2) M. McDonnell et Al., Cervical Spondylosis, stenosis, and Rheumatoid Arthritis, Medicine & Health/Rhode Island, Vol.95, No.4, April 2012. [2]Level of Evidence 5

3) L.Yang et Al., Plate-only Open-door Laminoplast Versus Laminectomy and Fusion fort he Treatment of Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy, Healio Orthopedics, Vol. 36, January 20132.[3]Level of Evidence 2B

4) H. Chikuda et Al., Optimal treatment for Spinal Cord Injury associated with Cervical canal Stenosis( OSCIS): a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial comparing early verus delayed surgery, BioMed Central, 2013.[4]Level of Evidence 1B

5) K.Yeh et Al., Expansive open-door laminoplasty secured with titanium miniplates is a good surgical method for multiple-level cervical stenosi, Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, August 2014.[5]Level of Evidence 2B

6) May, S. & Comer, C. Is surgery more effective than non-surgical treatment for spinal stenosis, and which non-surgical treatment is more effective? A systematic review. Physiotherapy, 2013, 99(1), 12-20. (Level of Evidence 1A)

7) Atlas SJ, Delitto A. Spinal stenosis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 443:198. (level of evidence: 5)

8) Hu SS, et al. Cervical spondylosis section of Disorders, diseases, and injuries of the spine. In HB Skinner, ed., Current Diagnosis and Treatment in Orthopedics, 4th ed., pp. 238–242. New York: McGraw-Hill.,2006 (level of evidence: 5)

9) Li X, Li J, Wu X. “Incidence, risk factors and treatment of cervical stenosis after radical trachelectomy: A systematic review.” European Journal of Cancer (2015) Sep;51(13):1751-9. LoE: 1A

10) Desai SK, et al. “Isolated cervical spinal canal stenosis at C-1 in the pediatric population and in Williams syndrome.” J Neurosurg Spine. 2013 Jun;18(6):558-63. LoE:

11) Aboulker J, Metzger J, David M., Engel P., Ballivet J. (1965) Les myèlopathies cervicales d’origine rachidienne. Neurochirurgie 11: 89-198. LoE:

12) Payne E., Spillane J. (1957) The cervical spine. An Anatomicopathological study of 70 specimens (using a special technique) with particular reference to the problem of cervical spondylosis. Brain 80: 571. LoE:

13) João Levy M., António Fernandes F., João Lobo A. “Neurologic aspects of systemic disease part I.” Handbook of clinical neurology: Chapter 35- Spinal Stenosis (2014) Volume 119; pg 541-549.LoE:5

14) Denaro V. “Stenosis of the cervical spine: causes, diagnosis, treatment” (1991) Springer- verlag Berlin Heidelberg. Pg. 6-26. LoE: 5

15) Boni M, Denaro V. “The cervical stenosis syndrome.” Int Ortho (1982) p:185-195. LoE:

16) Hashizume Y, Lijima S, Kishimoto H, et al. “Pathology of spinal cord lesions caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament.” (1984) Acta neuropathol (Berlin) 63: 123-130.

17) Y. Yukawa et Al., Laminoplasty and Skip Laminoplasty for Cervical Compressive Myelopathy, Spine, 2007.[17]Level of Evidence 2B