Plantar Fasciitis

Original Editor - Brooke Kennedy

Top Contributors - Admin, Kris Porter, Rachael Lowe, Elien Lebuf, Bert Pluym, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Kim Jackson, Jonathan Wong, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Brooke Kennedy, Lucinda hampton, Scott Buxton, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Jeroen Van Cutsem, Thomas Janicky, Elke Lathouwers, Vidya Acharya, Lisa Couck, Kai A. Sigel, Aminat Abolade, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Tony Lowe, Khloud Shreif, Rishika Babburu, Padraig O Beaglaoich, Jessica Galasso, Sehriban Ozmen, Shaimaa Eldib, Yahya Al-Razi, Claire Knott, Saud Alghamdi, David Csepe, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell, Jarapla Srinivas Nayak, Keta Parikh, Stijn Van de Vondel, WikiSysop and Habibu Salisu Badamasi

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Plantar fasciitis (Currently better referred to as Plantar Heel Pain) is the result of collagen degeneration of the plantar fascia at the origin, the calcaneal tuberosity of the heel as well as the surrounding perifascial structures.[1]

- The plantar fascia plays an important role in the normal biomechanics of the foot.

- The fascia itself is important in providing support for the arch and providing shock absorption.

- Despite containing "itis," this condition is characterized by an absence of inflammatory cells, hence it is considered degenerative, and not an inflammatory pathology[2][1]. As such, “fasciosis” or “fasciopathy” are increasingly used to refer to this condition[3].

The pathology is characterized by medial heel pain that worsens with weight-bearing, as well as after rest or non-weight bearing[4]. Plantar fasciitis often presents chronically with symptoms lasting over a year in duration[5].

There are many different sources of pain in the plantar heel beside the plantar fascia and therefore the term "Plantar Heel Pain" serves best to include a broader perspective when discussing this and related pathology.

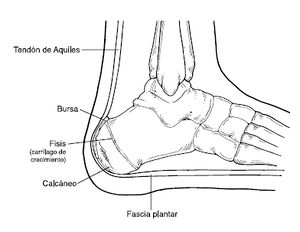

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

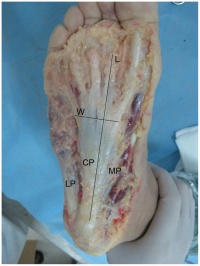

The plantar fascia

- Comprised of white longitudinally organized fibrous connective tissue which originates on the periosteum of the medial calcaneal tubercle, where it is thinner but it extends into a thicker central portion.

- The thicker central portion of the plantar fascia then extends into five bands surrounding the flexor tendons as it passes all 5 metatarsal heads.

- Pain in the plantar fascia can be insertional and/or non-insertional and may involve the larger central band, but may also include the medial and lateral band of the plantar fascia.

- Blends with the paratenon of the Achilles tendon, the intrinsic foot musculature, skin, and subcutaneous tissue.[6][7]

- This thick elastic multilobular fat pad is responsible for absorbing up to 110% of body weight during walking and 250% during running and deforms most during barefoot walking vs. shod walking.[8]

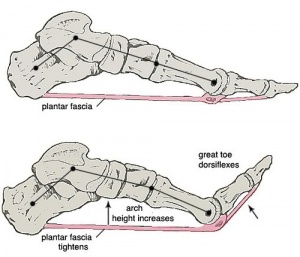

During weight-bearing:

- Tibia loads the foot “truss” and creates tension through the plantar fascia (windlass mechanism see R).

- The tension created in the plantar fascia adds critical stability to a loaded foot with minimal muscle activity.[9][10][11]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Often presents as an overuse injury, primarily due to repetitive strain causing micro-tears of the plantar fascia but can occur as a result of trauma or other multifactorial causes.

There are many risk factors for plantar heel pain including but not limited too:

- Reduced dorsiflexion and first metatarsophalangeal joint extension are weakly associated[12]

- Increased plantar flexion range[13]

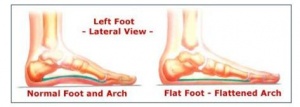

- Pes cavus or pes planus deformities

- Excessive foot pronation dynamically

- Impact/weight-bearing activities such as prolonged standing, running, etc

- Improper shoe fit

- Elevated BMI

- Presence of a sub calcaneal spur[15]

- Diabetes Mellitus (and/or other metabolic condition)

- Leg length discrepancy

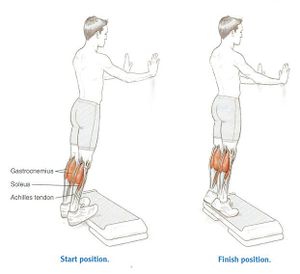

- Tightness and/or weakness of Gastrocnemius, Soleus, Tendoachilles tendon and intrinsic muscle.[16]

- Low-quality evidence suggests an association between weight-bearing activities and plantar fasciitis[17].

A 2016 systematic review found strong evidence for 3 associations for plantar fasciitis; a thickened plantar fascia, the presence of a sub calcaneal spur, and a high BMI in a non-athletic population[15].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of heel pain presenting in the outpatient setting.

- Affects 4% - 7% of the community [18] [19]

- Most prevalent between 40 and 60 years of age and accounts for 15% of foot injuries in the general population[20].

- Estimated to account for 8% of all running injuries. [19]

- 83% of these patients being active working adults between the ages of 25 and 65 years old

- 11% to 15% of all foot symptoms require professional medical care.

- May present bilaterally in a third of the cases[2].

- The average plantar heel pain episode lasts longer than 6 months and it affects up to 10-15% of the population.

- Approximately 90% of cases are treated successfully with conservative care.[21][22][23].

- Females present with plantar fasciitis slightly more commonly than males.[24]

- In the US alone, there are estimates that this disorder generates up to 2 million patient visits per year, and account for 1% of all visits to orthopaedic clinics.

- Plantar heel pain is the most common foot condition treated in physical therapy clinics and accounts for up to 40% of all patients being seen in podiatric clinics.[25]

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

Plantar fasciitis is a clinical diagnosis. It is based on patient history and physical examination.

- Patients can have local point tenderness along the anteromedial of the calcaneum, pain on the first steps, or after training.

- Plantar fasciitis pain is especially evident upon the dorsiflexion of the patient's pedal phalanges, which further stretches the plantar fascia. Therefore, any activity that would increase the stretch of the plantar fascia, such as walking barefoot without any arch support, climbing stairs, or toe walking can worsen the pain.

- Clinical examination will take into consideration a patient's medical history, physical activity, foot pain symptoms, and more.

- The doctor may decide to use imaging modalities like radiographs, diagnostic ultrasounds, and MRIs.

Look for the following:

- reproduced by palpating the plantar medial calcaneal tubercle at the site of the plantar fascial insertion on the heel bone.

- Pain reproduced with passive dorsiflexion of the foot and toes.

- Windlass Test - Passive dorsiflexion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (test to provoke symptoms at the plantar fascia by creating maximal stretch), positive test if the pain is reproduced.[2] (shown in 40-second video below)

Secondary findings may include

- Tight Achilles heel cord, pes planus (see R), or pes cavus.

- Altered gait (look for biomechanical factors that may predispose the client to plantar fascia problems) or predisposing factors mentioned previously.

- Obesity

- Work-related weight-bearing

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Heel pain with first steps in the morning or after long periods of non-weight bearing

- Tenderness to the anterior medial heel

- Limited dorsiflexion and tight achilles tendon

- A limp may be present or may have a preference to toe walking

- Pain is usually worse when barefoot on hard surfaces and with stair climbing

- Many patients may have had a sudden increase in their activity level prior to the onset of symptoms

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

Take into consideration a patient's medical history, physical activity, and foot pain symptoms.

Diagnostic Procedure[edit | edit source]

Ultrasonography is the most used imaging modality for this condition, and plantar fascia thickness is most often assessed - meta-analysis showed patients with plantar fasciitis have a plantar fascia 2.16 mm thicker when compared to a control group, and typically had plantar fascia thickness of 4.0 mm and above[27].

Some evidence suggests that patients with plantar fasciitis have a “softer” plantar fascia, and sonoelastography could detect this - identifying plantar fasciitis in symptomatic patients with normal ultrasound findings[28].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative measures are the first choice:

- Relative rest from offending activity as guided by pain level should be prescribed.

- Ice after activity as well as oral or topical NSAIDs can be used to help alleviate pain.

- Deep friction massage of the arch and insertion.

- Shoe inserts or orthotics and night splints may be prescribed in conjunction with the above.

- Educate patients on proper stretching and rehab of the: plantar fascia; achilles' tendon; gastrocnemius; and soleus.

If the pain does not respond to conservative measures:

- Corticosteroid injections

- Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP)[32]

- Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy [33]

- In three meta-analyses, ESWT showed greater VAS score reduction and over a 60% success rate of reducing heel pain over placebo[34][35][36].

- A systematic review by Sun et al. found ESWT had higher Roles and Maudsley scores, greater VAS score reduction, decreased return to work time, and fewer complications to other interventions - placebo, ultrasound, and endoscopic plantar fasciotomy[37]

- Needling Therapies

- Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT)

- Prolotherapy

- Iontophoresis

- Endoscopic Plantar Fasciotomy

- Important that advanced and invasive techniques be combined with conservative therapies.

- Surgery should be the last option if this process has become chronic and other less invasive therapies have failed[2]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

An important tool is patient education:

- Patients need to be told that symptoms may take weeks or even months to improve (depending on the circumstances of the injury).

- To follow the advice given eg rest from aggravating activities initially, ice, and stretch.

- Be aware of the importance of a home exercise plan[2]

The Clinical Practice Guidelines provide recommended physical therapy interventions based on available evidence. Interventions most recommended include manual therapy, stretching, taping, foot orthoses, and night splints.[38]

- Manual Therapy should include soft tissue and joint mobilization.[38]

- Myofascial release can be helpful in reducing pain[39].

- Stretching should include the plantar fascia and gastrocnemius/Soleus complex.[38]

- Stretching the plantar fascia consists of the patient crossing the affected leg over the contralateral leg and using the fingers across the base of the toes to apply pressure into the toe extension until a stretch can be felt along the plantar fascia. [40]

- Achilles’ tendon stretching can be performed in a standing position with the affected leg placed behind the contralateral leg with the toes pointed forward. The front knee is then bent, keeping the back knee straight and the heel on the ground. The back knee could then be in a flexed position for more of a soleus stretch.

- A systematic review found moderate quality evidence favouring plantar fascia-specific stretching (PFSS) over the Achilles tendon or calf stretching (CS) for short-term (< 3 months) pain relief[41].

- Taping should prevent pronation.[38]Low dye is the most commonly used taping technique and can improve pain in the short term, yet there is lacking evidence for its long-term effects[42]. A combined approach of taping with stretching may yield better results than stretching alone[42].

- Foot orthoses can be prefabricated or custom. They must support the medial longitudinal arch and provide cushioning to the heel. [38]

- If the patient has pain with initial steps in the morning, a night splint would be beneficial. [38]

- Posterior-night splints maintain ankle dorsiflexion and toe extension, allowing for a constant stretch on the plantar fascia

According to the Clinical Practice Guidelines, ultrasound, electrotherapy, and dry needling cannot be recommended. There is some support for low-level laser, phonophoresis with ketoprofen gel, change in footwear, weight loss, therapeutic exercise, and neuromuscular re-education. Meanwhile, shockwave diathermy is considered outside of physiotherapy practice according to the American Physical Therapy Association Clinical Practice Guidelines 2023 review.[38][43]

- Footwear should include a rocker-bottom shoe.[38]

- If weight is a concern, the patient should be referred to a more appropriate healthcare provider for nutritional advice.

- Therapeutic exercise and neuromuscular re-education should focus on reducing pronation and improving weight distribution in weight bearing. [38]

- Similar to tendinopathy management, high-load strength training appears to be effective in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. High-load strength training may aid in a quicker reduction in pain and improvements in function.[44]. The systematic review suggests there is minimal evidence to support the use of foot muscle training in patients with plantar fasciitis.[45]

Plantar fascia stretching video provided by Clinically Relevant

| [46] | [47] |

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Neurological - abductor digiti quinti nerve entrapment, lumbar spine disorders, problems with the medial calcaneal branch of the posterior tibial nerve, tarsal tunnel syndrome

- Soft tissue - Achilles Tendinopathy, fat pad atrophy, heel contusion, plantar fascia rupture, posterior tibial tendonitis, retrocalcaneal bursitis

- Skeletal - Severs' disease, calcaneal stress fracture, infections, inflammatory arthropathies, subtalar arthritis

- Miscellaneous - metabolic disorders, osteomalacia, Paget's disease, sickle cell disease, tumours (rare), vascular insufficiency, Rheumatoid arthritis

Concluding Comments[edit | edit source]

- Thorough patient education is needed.

- Usually a self-limiting condition, and with conservative therapy, symptoms are usually resolved within 12 months of initial presentation and often sooner.

- Sometimes more chronic cases of this condition will need additional follow-up to consider more advanced therapies and evaluation of gait and biomechanical factors that can potentially be corrected through gait retraining.

- Corticosteroid injections have been shown to be beneficial in the short term (less than four weeks) but ineffective in the long term.

- Evidence of the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma, dex prolotherapy, and extra-corporeal shockwave therapy is conflicting[2].

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clinical practice Guideline (Heel Pain – Plantar Fasciitis: Revision 2023)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lemont H, Ammirati KM, Usen N. Plantar fasciitis: a degenerative process (fasciosis) without inflammation. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2003 May 1;93(3):234-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Buchanan BK, Kushner D. Plantar fasciitis. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431073/ (last accessed 22.6.2020)

- ↑ Rhim HC, Kwon J, Park J, Borg-Stein J, Tenforde AS. A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews on the Epidemiology, Evaluation, and Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis. Life. 2021 Dec;11(12):1287.

- ↑ Schepsis AA, Leach RE, GOUYCA J. Plantar fasciitis: etiology, treatment, surgical results, and review of the literature. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (1976-2007). 1991 May 1;266:185-96.

- ↑ Klein SE, Dale AM, Hayes MH, Johnson JE, McCormick JJ, Racette BA. Clinical presentation and self-reported patterns of pain and function in patients with plantar heel pain. Foot & ankle international. 2012 Sep;33(9):693-8.

- ↑ Carlson RE, Fleming LL, Hutton WC. The biomechanical relationship between the tendoachilles, plantar fascia and metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion angle. Foot & Ankle International. 2000 Jan;21(1):18-25.

- ↑ Stecco C, Corradin M, Macchi V, Morra A, Porzionato A, Biz C, De Caro R. Plantar fascia anatomy and its relationship with Achilles tendon and paratenon. Journal of anatomy. 2013 Dec;223(6):665-76.

- ↑ Gefen A, Megido-Ravid M, Itzchak Y. In vivo biomechanical behavior of the human heel pad during the stance phase of gait. Journal of biomechanics. 2001 Dec 1;34(12):1661-5.

- ↑ Tweed JL, Barnes MR, Allen MJ, Campbell JA. Biomechanical consequences of total plantar fasciotomy: a review of the literature. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2009 Sep 1;99(5):422-30.

- ↑ Cheung JT, An KN, Zhang M. Consequences of partial and total plantar fascia release: a finite element study. Foot & ankle international. 2006 Feb;27(2):125-32.

- ↑ Crary JL, Hollis JM, Manoli A. The effect of plantar fascia release on strain in the spring and long plantar ligaments. Foot & ankle international. 2003 Mar;24(3):245-50.

- ↑ Irving DB, Cook JL, Menz HB. Factors associated with chronic plantar heel pain: a systematic review. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2006 May 1;9(1-2):11-22.

- ↑ Hamstra-Wright KL, Huxel Bliven KC, Bay RC, Aydemir B. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis in physically active individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports health. 2021 May;13(3):296-303.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Butterworth PA, Landorf KB, Smith SE, Menz HB. The association between body mass index and musculoskeletal foot disorders: a systematic review. Obesity reviews. 2012 Jul;13(7):630-42.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Van Leeuwen KD, Rogers J, Winzenberg T, van Middelkoop M. Higher body mass index is associated with plantar fasciopathy/‘plantar fasciitis’: systematic review and meta-analysis of various clinical and imaging risk factors. British journal of sports medicine. 2016 Aug 1;50(16):972-81.

- ↑ Lemont H, Ammirati KM, Usen N. Plantar fasciitis: a degenerative process (fasciosis) without inflammation. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2003 May 1;93(3):234-7.

- ↑ Waclawski ER, Beach J, Milne A, Yacyshyn E, Dryden DM. Systematic review: plantar fasciitis and prolonged weight bearing. Occupational Medicine. 2015 Mar 1;65(2):97-106.

- ↑ Thomas MJ, Whittle R, Menz HB, Rathod‐Mistry T, Marshall M, Roddy E. Plantar heel pain in middle-aged and older adults: population prevalence, associations with health status and lifestyle factors, and frequency of healthcare use. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders [Internet]. 2019 Jul 20;20(1).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Morrissey D, Cotchett M, J’Bari AS, Prior T, Griffiths IB, Rathleff MS, et al. Management of plantar heel pain: a best practice guide informed by a systematic review, expert clinical reasoning and patient values. British Journal of Sports Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Mar 30;55(19):1106–18.

- ↑ Agyekum EK, Ma K. Heel pain: A systematic review. Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2015 Jun 1;18(03):164-9.

- ↑ McPoil TG, MaRtin RL, Cornwall MW, Wukich DK, Irrgang JJ, Godges JJ. Heel pain—plantar fasciitis. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2008 Apr;38(4):A1-8.

- ↑ Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. JBJS. 2003 May 1;85(5):872-7.

- ↑ Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, Mendicino RW, Schuberth JM, Vanore JV, Weil Sr LS, Zlotoff HJ, Bouché R, Baker J. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline–revision 2010. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2010 May 1;49(3):S1-9.

- ↑ Lopes AD. Hespanhol Junior, LC, Yeung, SS, Costa, LO, 2012. What are the main running-related musculoskeletal injuries.:891-905.

- ↑ Al Fisher Associates, Inc. 2002 Podiatric Practice Survey: Statistical Results. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2003 Jan;93(1):67-86.

- ↑ Kate Cornet. Windlass Test. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZO0wREhjxH0 [last accessed 11/3/2023]

- ↑ Rhim HC, Kwon J, Park J, Borg-Stein J, Tenforde AS. A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews on the Epidemiology, Evaluation, and Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis. Life. 2021 Dec;11(12):1287.

- ↑ Fusini F, Langella F, Busilacchi A, Tudisco C, Gigante A, Massé A, Bisicchia S. Real-time sonoelastography: principles and clinical applications in tendon disorders. A systematic review. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2017 Jul;7(3):467.

- ↑ David JA, Sankarapandian V, Christopher PR, Chatterjee A, Macaden AS. Injected corticosteroids for treating plantar heel pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(6).

- ↑ Li Z, Yu A, Qi B, Zhao Y, Wang W, Li P, Ding J. Corticosteroid versus placebo injection for plantar fasciitis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2015 Jun 1;9(6):2263-8.

- ↑ Peña-Martínez VM, Acosta-Olivo C, Simental-Mendía LE, Sánchez-García A, Jamialahmadi T, Sahebkar A, Vilchez-Cavazos F, Simental-Mendía M. Effect of corticosteroids over plantar fascia thickness in plantar fasciitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 2023 Jun 11(just-accepted).

- ↑ Yu T, Xia J, Li B, Zhou H, Yang Y, Yu G. Outcomes of platelet-rich plasma for plantar fasciopathy: a best-evidence synthesis. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2020 Dec;15:1-9.

- ↑ Al-Abbad H, Allen S, Morris S, Reznik J, Biros E, Paulik B, Wright A. The effects of shockwave therapy on musculoskeletal conditions based on changes in imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2020 Dec;21(1):1-26.

- ↑ Sun J, Gao F, Wang Y, Sun W, Jiang B, Li Z. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is effective in treating chronic plantar fasciitis: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Medicine. 2017 Apr;96(15).

- ↑ Aqil A, Siddiqui MR, Solan M, Redfern DJ, Gulati V, Cobb JP. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is effective in treating chronic plantar fasciitis: a meta-analysis of RCTs. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2013 Nov;471:3645-52.

- ↑ Lou J, Wang S, Liu S, Xing G. Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy without local anesthesia in patients with recalcitrant plantar fasciitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2017 Aug 1;96(8):529-34.

- ↑ Sun K, Zhou H, Jiang W. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy versus other therapeutic methods for chronic plantar fasciitis. Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2020 Jan 1;26(1):33-8.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 38.7 38.8 Enseki K, Harris-Hayes M, White DM, Cibulka MT, Woehrle J, Fagerson TL, Clohisy JC. Nonarthritic hip joint pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classifiation of Functioning, Disability and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2014 Jun;44(6):A1-32.

- ↑ Piper S, Shearer HM, Côté P, Wong JJ, Yu H, Varatharajan S, Southerst D, Randhawa KA, Sutton DA, Stupar M, Nordin MC. The effectiveness of soft-tissue therapy for the management of musculoskeletal disorders and injuries of the upper and lower extremities: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Manual therapy. 2016 Feb 1;21:18-34.

- ↑ DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME, Moore EA, Murray JC, Wilding GE, Baumhauer JF. Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain: a prospective, randomized study. JBJS. 2003 Jul 1;85(7):1270-7.

- ↑ Siriphorn A, Eksakulkla S. Calf stretching and plantar fascia-specific stretching for plantar fasciitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2020 Oct 1;24(4):222-32.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Podolsky R, Kalichman L. Taping for plantar fasciitis. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. 2015 Jan 1;28(1):1-6.

- ↑ Martin RL, Davenport TE, Reischl SF, McPoil TG, Matheson JW, Wukich DK, McDonough CM, Altman RD, Beattie P, Cornwall M, Davis I. Heel pain—plantar fasciitis: revision 2014. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2014 Nov;44(11):A1-33.

- ↑ Rathleff MS, Mølgaard CM, Fredberg U, Kaalund S, Andersen KB, Jensen TT, Aaskov S, Olesen JL. High‐load strength training improves outcome in patients with plantar fasciitis: A randomized controlled trial with 12‐month follow‐up. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2015 Jun;25(3):e292-300.

- ↑ Rhim HC, Kwon J, Park J, Borg-Stein J, Tenforde AS. A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews on the Epidemiology, Evaluation, and Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis. Life. 2021 Dec;11(12):1287.

- ↑ gerrybphysio. Plantar Fasciitis taping that works. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pe6UEck_hIY [last accessed 11/3/2023]

- ↑ TheProactiveAthlete. Plantar Fascia Exercises. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kStuJAu0a20 [last accessed 6/6/2009]