Universal Health Care

Original Editors - Habibu Salisu Badamasi and ReLAB-HS

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Vidya Acharya, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Manisha Shrestha, Ashmita Patrao, Oyemi Sillo and Tarina van der Stockt

Introduction[edit | edit source]

"Health is the most fundamental human right on which all other rights can be enjoyed. Universal Health Coverage is its guarantee." Dr. Githinji Gitahi [1]

Universal Health Care (UCH) is understood in a variety of ways. It involves judgments about who the potential recipients are, what is the range of services included within health care, and the quality of that care? [2] Universal health care and universal health coverage were often fused into one entity, but each term, as used by researchers, addresses five main themes:

- accessibility to health care by its intended recipients,

- broad population coverage,

- package of point-of-entry healthcare services,

- healthcare access based on rights and entitlements, and

- protection from the social and economic consequences of illness.

The term “Universal Health Care” has most frequently been used in describing policies for care in high-income countries, while “Universal Health Coverage” (UHC) has most often been applied to low- and middle-income countries. [3]

The WHO has defined UHC as “ensuring that all people have access to needed health services (including prevention, promotion, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliation) of sufficient quality to be effective while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user the financial hardship. [4]

Universal Health Coverage is the key to improving the well-being of a country’s population, investment in human capital, and a foundational driver of inclusive and sustainable economic growth and development. It is a way to support people so they can reach their full potential and fulfil their aspirations. Achieving universal health coverage (UHC) is one of the 17 sustainable development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015 -Target 3.8 of SDG 3; which include financial risk protection, access to quality essential health- care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.[4]

Dimensions of Universal Health Care[edit | edit source]

The World Health Report 2010 presents a cube in fig 2 below to help policy-makers think about the potential trade-offs in benefit design for UHC with the following three dimensions:[5]

- Who benefits from pooled resources?

- For what services?

- At what cost at the post of use?

For effective coverage, the depth axis on which benefits are covered (service coverage) must be defined in terms of needed and effective services of good quality. The height axis on cost should reflect relative ability to pay in order to assess the affordability of care. The breadth axis who is insured ensures that the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable are effectively covered first and at an affordable cost.

Access to Care[edit | edit source]

Universal Health Coverage aims to provide every citizen or resident access to Insurance or a particular set of services. Usage included “Everyone can get insurance”, as well as certain services, such as “Access to essential medicines” and outcomes, “Access to care with financial risk protection”; Financing for universal coverage is based on two interlinked foundations. The first is to ensure that financial barriers do not prevent people from using the services they need–prevention, promotion, treatment and rehabilitation. The second is to ensure that they do not suffer financial hardship because they have to pay for these services. [6]

UHC with Universal Access is equated to be similar by some organizations including the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and American Medical Associations. One concern is that persons may achieve the financial, geographic, and legal means of access to health service and protection, but face cultural or social barriers to care. [3]

Coverage[edit | edit source]

Universal coverage was referred to as 100% coverage of the population under the given health plan or comprehensive health coverage without user fees. However, which services should be fully covered, who should be covered, and what services are considered necessary for coverage to be comprehensive is unclear.[3]

Until 2017, the UNGA adopted a specific indicator for measuring coverage: SDG target 3.8.1. The coverage of essential health services (defined as the average coverage of essential services based on tracer interventions that include reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases and service capacity and access, among the general and the most disadvantaged population). The UHC service coverage index has a value of 64 (out of 100) globally, with values ranging from 22 to 86 across countries in 2015. [4]

Package of Services[edit | edit source]

This approach seeks to identify a “universal package of guaranteed benefits or entitlements, comprising a set of essential services applied to all in the world. This includes a basket of services containing the basic drugs and services set out in the WHO Primary Health Care. [3]

Rights-based Approach of UHC[edit | edit source]

This refers to as ensuring the “highest attainable standard of health, encompassing medical care, access to safe drinking water, adequate sanitation, education, health-related information, and other underlying determinants of health. The rights-based approach starts from the position that health is a human right. This right to health further is disaggregated into negative liberties, such as the ‘right to be free from discrimination and involuntary medical treatment’, and positive ones, such as ‘the right to essential primary health care.[3]

Social and Economic Risk Protection[edit | edit source]

Universal social health protection coverage is defined as “effective access to affordable health care of adequate quality and financial protection in case of sickness”. It is associated especially with the International Labor Organization (ILO), which defines social health protection as a ‘series of public or publicly organized and mandated private measures against social distress and economic loss caused by the reduction of productivity, stoppage or reduction of earnings or the cost of necessary treatment that can result from ill-health. [3]

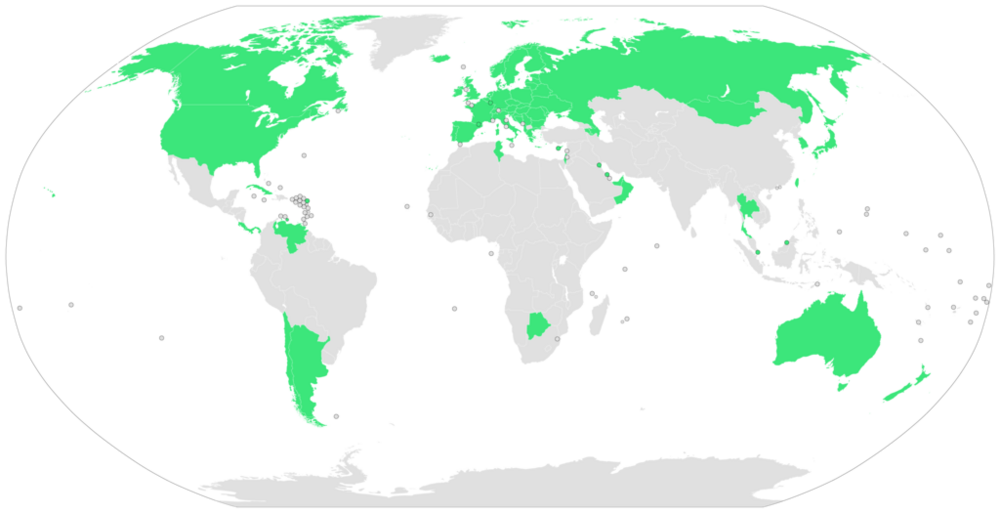

Global Prevalence of Universal Health Coverage[edit | edit source]

There is no single list of countries fulfilling the WHO definition of UHC, based on explicit criteria. However, the ILO has compiled a list of 190 countries, accompanied by an index of social health protection, which combines data on the legal status of coverage and quantitative measures, such as the level of health expenditure, out-of-pocket payments, and access indicators.[3]

The global monitoring report 2017 revealed that at least half the world’s population still lacks access to essential health services and that about 100 million people are pushed into extreme poverty each year due to their health expenditures.[4]

The Global Monitoring Report on financial Protection in Health 2019 focuses on this second dimension of UHC- financial hardship from out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenses. The report looks at how many people globally are pushed into poverty by OOP payment and how much such a payment takes up more than 10% or (25%) of their consumption or income (so-called ‘catastrophic’ expenditures). Globally, about 925 million people spend more than 10% of their household income on health care, and over 200 million spend more than 25%. In recent years, out-of-pocket expenditures have fallen at the $1.90-a-day and $3.20-a-day poverty lines.[4]

Pillars of Universal Health Coverage[edit | edit source]

Three pillars are identified as being needed to support a UHC strategy, and they are fundamental, interrelated problems restricting countries from closer to universal coverage. The intersection of these three pillars aims to create an environment in which UHC is a measurable and achievable goal.[6]

- Raising sufficient funds to ensure the availability of health services that meet the major health needs of the population. In order to do this, it is suggested that countries need to:

- Increase the efficiency of revenue collection

- Re-prioritise government budgets to give money to health

- Explore innovative financing opportunities like taxes on air tickets, foreign exchange transactions, or tobacco

- Access development assistance(aid) for health

- Reducing reliance on out-of-pocket payments (where people pay directly for health services they use) as a way to finance health services. Instead of charging fees for health services, the report recommends using tax or insurance schemes to finance health services. This reduces financial risk for individuals and shares risk across the population. Poor people will need subsidized health services, and payment through tax or insurance should be compulsory for those who can afford it, or people with low risk will opt out of the payment system.

- Reducing inefficient and inequitable use of resources during the process of delivering health care: All people, regardless of disease or condition; age, gender, race or ethnic background; sexual orientation; geographic location; socio-cultural background, economic or legal status, must have fair and impartial access to quality healthcare. The legacy of inequality can be tackled by both “financing gap” and a “provision gap”: The financing gap( or lower per capita spending on the poor) by spending additional resources in a pro-poor way; the provision gap (or underperformance of service delivery for the poor) by expanding supply and changing incentives. [7] The main strategies proposed to achieve this are:

- Selecting appropriate technologies and services

- Motivating health workers

- Improving hospital efficiency

- Reducing medical errors

- Eliminating waste and corruption in the health system

- Critically assessing what services are needed

- Reducing inequalities in coverage

- Interrelated components of universal health

Resources[edit | edit source]

UHC 2030[edit | edit source]

UHC2030 is the global movement to build stronger health systems for universal health coverage. It provides a platform to convene and build connections through joint high-level events or gathering of experts and contributes advocacy, tools, guidance, knowledge and learning.

World Health Organisation[edit | edit source]

World Bank[edit | edit source]

- Universal Health Coverage for Inclusive and Sustainable Development

- Univseral Health Coverage Study Series

Rockefeller Foundation[edit | edit source]

International Alliance of Patients Organisations (IAPO)[edit | edit source]

Multimedia Resources[edit | edit source]

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ Dr. Githinji Gitahi ,UHC Day 2018 Global CEO, Amref Health Africa Co-chair, UHC 2030 Steering Committee.

- ↑ McKee M, Balabanova D, Basu S, Ricciardi W, Stuckler D. Universal health coverage: a quest for all countries but under threat in some. Value in Health. 2013 Jan 1;16(1):S39-45.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Stuckler D, Feigl AB, Basu S, McKee M. The political economy of universal health coverage. InBackground paper for the global symposium on health systems research. Geneva: World Health Organization 2010 Nov 16 (Vol. 2010).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 World Health Organization. Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report

- ↑ Ochalek J, Manthalu G, Smith PC. Squaring the cube: Towards an operational model of optimal universal health coverage. Journal of health economics. 2020 Mar 1;70:102282.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Etienne C, Asamoa-Baah A, Evans DB. Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. World Health Organization; 2010.

- ↑ Cotlear D, Nagpal S, Smith O, Tandon A, Cortez R. Going universal: how 24 developing countries are implementing universal health coverage from the bottom up. World Bank Publications; 2015 Sep 28.