Tackling Physical Inactivity: A Resource for Raising Awareness in Physiotherapists: Difference between revisions

Jason Chang (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (494 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors '''- [[User:Jason Chang| | '''Original Editors '''- [[User:Jason Chang|Jason Chang]], [[User:Andrea Christoforou|Andrea Christoforou]], [[User:Maria Cuddihy|Maria Cuddihy]], [[User:Christine Gorsek|Christine Gorsek]], [[User:Annika Hobler|Annika Höbler]] as part of the [[Current_and_Emerging_Roles_in_Physiotherapy_Practice|Queen Margaret University's Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | |||

= | == Introduction == | ||

[[Physical Inactivity|Physical inactivity]] has been deemed "the biggest [[Public Health and Physical Activity|public health]] problem of the 21st century"<ref name="Blair 2009">Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century [warm up].J Sports Med 2009;43(1):1-2.</ref> and has been shown to kill more people than [[Smoking Cessation and Brief Intervention|smoking]], [[diabetes]] and [[obesity]] combined (Figure 1)<ref name="Khan">Khan KM, Tunaiji HA. As different as Venus and Mars: time to distinguish efficacy (can it work?) from effectiveness (does it work?) [warm up]. Br J Sports Med 2011;45(10):759-760.</ref>. It is ranked as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, killing approximately 3.2 million people (~6% of the total deaths) annually and accounting for approximately 32.1 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs; ~2.1% of global DALYs) annually<ref name="GHO">Global Health Observatory (GHO). Prevalence of physical inactivity 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/index.html (Accessed 20 November 2013).</ref>.[[Image:Fig. 1 Obesity.jpg|thumb|395x395px|Figure 1.Percentage of deaths attributable to low fitness (i.e. inactivity) compared to smoking (s), diabetes (d) and obesity (o) combined - in men (m) and women (w). |alt=|center]]See [[Physical Inactivity]] Link | |||

Physical inactivity has been deemed the | |||

{| width=" | <br>The YouTube video by Dr. Mike Evans below provides a stimulating and compelling overview of the evidence, with some key points highlighted in the box to the right:<div class="coursebox"> | ||

{| class="FCK__ShowTableBorders" width="100%" cellspacing="4" cellpadding="4" border="0" | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | align="center" | | ||

'''23 and 1/2 Hours:''' <br> '''What is the single best thing we can do for our health?''' <ref name="DocMikeEvans">DocMikeEvans. 23 and 1/2 hours: What is the single best thing we can do for our health?. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUaInS6HIGo (Accessed 18 November 2013).</ref> | |||

| | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

{ | {{#ev:youtube|aUaInS6HIGo|350}} | ||

| | |||

|} | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

| | | | ||

Key Points: | '''Key Points:''' | ||

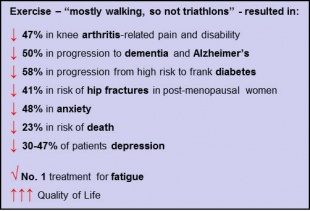

[[Image:DrMikeSays.jpg|311x211px]]<br> | [[Image:DrMikeSays.jpg|311x211px]]<br> | ||

[https://www.facebook.com/docmikeevans/posts/251831308232733 Key References | [https://www.facebook.com/docmikeevans/posts/251831308232733 Key References] | ||

|} | |} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Sedentary Behaviour == | |||

= | As emphasised in the video ''23 and ½ Hours'' and embraced by the latest [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Tackling_Physical_Inactivity:_A_Resource_for_Raising_Awareness_in_Physiotherapists#Guidelines physical activity guidelines], the ‘dose’ of physical activity that seems to confer the majority of these health benefits (in adults) is 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity on most days of the week<ref name="BlairLaMonte">Blair SN, LaMonte MJ, Nichaman MZ. The evolution of physical activity recommendation: how much is enough? Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79(5):913S-920S.</ref>. However, one aspect of physical activity promotion that this dose recommendation does not address is sedentary behaviour. See [[Sedentary Behaviour|Sedentary behaviour]] link. | ||

Given the amount of time potentially spent sitting each day evidence suggests that short breaks in sedentary time can confer substantial health benefits <ref name="Healy2008">Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Cerin E, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Owen N. Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk. Diabetes Care 2008;31(4):661-6.</ref><ref name="Healy2011">Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, Winkler EAH, Owen N. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003-06. Eur Heart J 2011;32(5):590-7.</ref>, as highlighted in the short video below. <div class="coursebox"> | |||

<div class="coursebox"> | {| class="FCK__ShowTableBorders" width="100%" cellspacing="4" cellpadding="4" border="0" | ||

{| width="100%" cellspacing="4" cellpadding="4" border="0 | |||

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" | | ||

'''Is Sitting On Your Backside Dangerous? ''' | '''Is Sitting On Your Backside Dangerous?'''<ref>Risk Bites. Is sitting on your backside dangerous?. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COIGHiMveG4 (Accessed 26 November 2013).</ref> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|COIGHiMveG4|350}} | |||

{ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

|} | |} | ||

</div>Thus, it is clear that the physical activity paradigm should incorporate sedentary behaviour<ref name="Katzmarzyk2010">Katzmarzyk PT. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and health: paradigm paralysis or paradigm shift? Diabetes 2010;59:2717-2725.</ref>, and physical activity initiatives and recommendations should adapt accordingly <ref name="Hamilton2008">Hamilton MT, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Zderic TW, Owen N. Too little exericse and too much sitting: inactivity physiology and the need for new recommendations on sedentary behavior. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports 2008;2(4):292-8.</ref><ref name="Yates2011">Yates T, Wilmot EG, Khunti K, Biddle S, Gorely T, Davies MJ. Stand up for your health: is it time to rethink the physical activity paradigm? Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2011;93(2):292-4.</ref>. | |||

== The Development and Evolution of Physical Activity Guidelines == | |||

< | Beginning with Morris’ work on occupational physical activity in the 1950s <ref name="Paff2001">Paffenbarger RS Jr, Blair SN, Lee IM. A history of physical activity, cardiovascular health and longevity: the scientific contributions of Jeremy N Morris, DSc, DPH, FRCP. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30(5):1184-92.</ref>, the evidence emerging from the years of epidemiological research of the risks associated with inactivity or a sedentary lifestyle provided the rationale for the development of physical activity guidelines<ref name="BlairLaMonte" />. Identifying the appropriate ‘dose’ of physical activity that would extract the greatest reward in public health requires an ongoing examination of data emerging from both epidemiological and exercise training studies. It also requires the decision to focus these recommendations on the population who would benefit most, namely those who are inactive, thus contributing to the public health burden<ref name="Lee2001">Lee IM, Skerrett PJ. Physical activity and all-cause mortality: what is the dose-response relation? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33(6):S459-71.</ref><ref name="BlairLaMonte" />. | ||

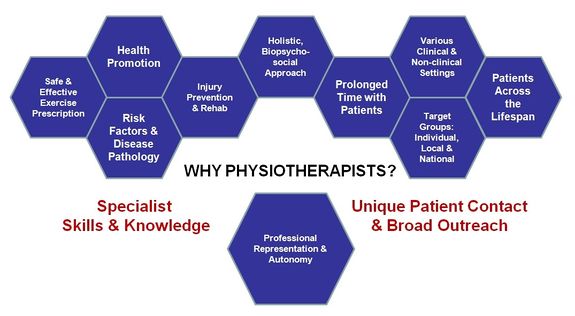

See [[Physical Activity]] link for guidelines and more.<br>Physiotherapists have the potential to make a substantial impact on individual, community and public health. Their holistic, biopsychosocial<ref name="Sanders2013">Sanders T, Foster NE, Bishop A, Ong BN. Biopsychosocial care and the physiotherapy encounter: physiotherapists’ accounts of back pain consultations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:65</ref>, and non-invasive approach, professional autonomy<ref name="HCPC2013">Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC). Physiotherapists: standards of proficiency. 2013. Available at: http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10000DBCStandards_of_Proficiency_Physiotherapists.pdf. (Accessed 3 December 2013).</ref>, specialist knowledge and skill set<ref name="WCPT2011">World Confederation for Physical Therapy. Policy statement: physical therapists as exercise experts across the life span. 2011. Available at: http://www.wcpt.org/policy/ps-exercise%20experts (Accessed 28 November 2013).</ref>, relatively prolonged patient contact time and varied clinical practice populations and settings (including [http://www.physio-pedia.com/An_overview_of_physiotherapy_in_UK_prisons prisons]) places the physiotherapist in the ideal position for the widespread promotion of physical activity (Figure 9)<ref name="Khan2013">Khan K. Guest editorial: physiotherapists as physical activity champions. Physiotherapy Practice 2013 Available at: http://sunshinephysio.com/resources/articles/PhysicalActivityChampions.pdf (Accessed 28 November 2013).</ref><ref name="Dean2009-1">Dean E. Physical therapy in the 21st century (Part I): Toward practice informed by epidemiology and the crisis of lifestyle conditions. Physiother Theory Prac 2009;25(5-6):330-353.</ref><ref name="Europa2012">Europa. Presentation of ER-WCPT commitment in the EU platform on diet, physical activity and health. 2012. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/ev20121114_co04_en.pdf (Accessed 28 November 2013).</ref>.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

[[Image:WhyPhysios.jpg|thumb|575x575px|Figure 9. Summary of why physiotherapists are in an ideal position to take the lead as 'physical activity champions'. (Figure adapted from Europa 2012 [presentation])|center]] | |||

In the past, physiotherapy intervention, including exercise prescription, has predominantly focused on the restoration of function lost as a result of an acute incident or on the maintenance of function in neurological or cardio-respiratory disease<ref name="Verhagen2009">Verhagen E, Engbers L. The physical therapist’s role in physical activity promotion. Br J Sports Med 2009;43(2):99-101</ref>. However, a shift in the public health agenda towards the prevention or management of chronic lifestyle conditions, including NCDs, obesity, osteoarthritis and depression<ref name="GHO2">Global Health Observatory (GHO). Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/en/index.html Accessed 20 November 2013.</ref>, and towards the mitigation of the effects of ageing in an increasingly ageing population<ref name="Spijker2013">Spijker J, MacInnes J. Population ageing: the timebomb that isn’t? Brit Med J 2013;347:f6598.</ref> has demanded a change in the role of the physiotherapist in addressing this need through the widespread promotion of physical activity (and other health-promoting lifestyle changes)<ref name="Dean2009-1" />. Recognising this emerging role and “professional and ethical responsibility”<ref name="Dean2009-1" />, physiotherapy professional bodies around the world have brought physical activity promotion to the forefront of their agenda with links to two clear examples - CSP and WCPT - provided below. | |||

== Physical Activity For The Individual == | |||

< | Physical activity promotion at the level of the individual is not a novel concept. As first points of contact, primary care providers, particularly GPs, have acknowledged a necessary role in physical activity promotion for decades, with varying degrees of follow-through in different countries<ref name="Weiler2010">Weiler R, Stamatakis E. Physical activity in the UK: a unique crossroad? Brit J Sports Med 2010;44:912-4</ref>. The various medical-practitioner-based physical activity schemes developed have typically involved (1) links to commercial exercise centres; (2) the provision of simple advice on physical activity or (3) a behavioural counselling approach to the provision of physical activity advice<ref name="Handcock2003">Handcock P, Jenkins C. The Green Prescription: a field of dreams? J New Zealand Med Assoc, 2003;116(1187):1-5.</ref>. | ||

== Assessing Physical Activity == | |||

Assessment is an important tool in the physiotherapist's arsenal, enabling the collection of relevant information for a clinically-reasoned, holistic and patient-centred approach to diagnosis and subsequent management. Despite the [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Tackling_Physical_Inactivity:_A_Resource_for_Raising_Awareness_in_Physiotherapists#Evidence evidence], patients’ habitual physical activity and sedentary levels are generally not assessed as part of the standard physiotherapy assessment<ref name="Petty2001">Petty N.J. Neuromusculoskeletal Examination and Assessment: A Handbook for Therapists. 2001. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.</ref>.Yet, all patients coming into contact with a physiotherapist suffer from and/or are susceptible to the effects of physical inactivity, regardless of their presenting complaint. Thus, the assessment of physical activity and sedentary levels has a relevant place in the physiotherapy examination<ref name="Hussey2003">Hussey J, Wilson F. Measurement of Activity Levels is an important part of physiotherapy assessment. Physiotherapy 2003;89(10):585-93.</ref>. | |||

In the general medicine community, physical activity has been declared the fifth vital sign<ref name="Sallis2010">Sallis R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:473-74</ref> – a modifiable sign that should be assessed at every clinical encounter<ref name="Sallis2010" /><ref name="KhanBMJ2011">Khan KM, Weiler R, Blair SN. Prescribing exercise in primary care. BMJ 2011;343</ref>. Different approaches may be used to measure levels of physical activity (e.g. observation, heart rate monitors, motion sensors), but questionnaires are likely to be the most appropriate in the context of a typical physiotherapy assessment, given time and resource constraints<ref name="Hussey2003" />. Three alternatives for the assessment of a patient’s physical activity levels are described below. | |||

=== The Kaiser Permanente Approach: The ‘Exercise Vital Sign’ === | |||

Kaiser Permanente is a not-for-profit, California-based integrated managed care consortium that have adopted a simple method for assessing physical activity levels in each patient, at every visit<ref name="Sallis2011">Sallis, R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:473-4</ref>. Coined the ‘Exercise Vital Sign' (EVS), it is a brief screening tool that consists of two questions and has shown good face and discriminant validity<ref name="Coleman2012">Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, Quinn VP, Koebnick C, Young DR, Sternfeld B, Sallis RE. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44(11):2071-6</ref>. It is described in the 40-second video below. | |||

<div class="coursebox"> | |||

{| class="FCK__ShowTableBorders" width="100%" cellspacing="4" cellpadding="4" border="0" | |||

|- | |||

| align="center" | | |||

'''Kaiser Permanente: ''' '''Making Exercise a Vital Sign'''<ref>AHIPResearch. Kaiser Permanente: Making Exercise a Vital Sign. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hxfp0LOaLMM Accessed 02 December 2013.</ref> | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|Hxfp0LOaLMM|350}} | |||

{ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

| | | | ||

<u>Key Points:</u> | |||

The EVS: "2 questions, 1 minute" <ref name="Sallis2010" /> | |||

1) “On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate or greater physical activity?” <br> | |||

2) “On those days, how many minutes do you engage in activity at this level?” | |||

|} | |} | ||

</div> | |||

== Mobilising Behaviour Change == | == Mobilising Behaviour Change == | ||

Physical activity | Physical activity is a complex, multifactorial (Figure 3) and multi-dimensional (Figure 7) health behaviour<ref name="Bauman2012">Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not?. Lancet 2012;380(9838):258-71.</ref><ref name="Pettee2012">Pettee Gabriel KK, Morrow JR Jr, Woolsey AL. Framework for physical activity as a complex and multidimensional behaviour. J Phys Act Health 2012;9(Suppl 1):S11-8.</ref>. The role of the physiotherapist in counselling a patient to adopt, change or maintain such a behaviour can be equally complex. It may involve forming a partnership with the patient<ref name="Jonas2009">Jonas S, Phillips EM. ACSM’s Exercise is MedicineTM: A Clinician’s Guide to Exercise Prescription. American College of Sports Medicine 2009 Philadelphia.</ref>, defining the target behaviour (e.g. increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary behaviour), exploring and addressing the unique combination of personal, socio-cultural, environmental, policy factors underlying the patient’s behaviour<ref name="Bauman2012" /> <ref name="Sluijs1993">Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J. Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther 1993;73(11):771-82.</ref> and identifying the most suitable (patient-centred) approach(es) to mobilise and help the patient sustain the behaviour<ref name="Steptoe2001">Steptoe A, Kerry S, Rink E, Hilton S. The impact of behavioural counselling on stage of change in fat intake, physical activity, and cigarette smoking in adults at increased risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Public Health 2001;91(2):265-9.</ref>. Long-term adherence to physical activity is essential for the health benefits to be realised<ref name="Middleton2013">Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-Term Adherence to Health Behavior Change. Am J Lifestyle Medicine 2013:1-10.</ref>.<br><br>Several theoretical models of and counselling approaches for health behaviour change have been developed<ref name="Dean2009-2">Dean E. Physical therapy in the 21st century (Part II): Evidence-based practice within the context of evidence-informed practice. Physiother Theory Prac 2009;25(5-6):354-68.</ref><ref name="Elder1999">Elder JP, Ayala GX, Harris S. Theories and intervention approaches to health-behaviour change in primary care. Am J Prev Med 1999;17(4):275-84.</ref>. A working knowledge of these models and the various approaches to their practical application is another essential tool in the physiotherapist’s arsenal, if s/he is to help effect and sustain behaviour change in the patient.<br> | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | A summary of these models and approaches is provided below.<br> | ||

< | === Theoretical Models of Health Behaviour Change === | ||

Table 2 provides a brief description of and practical suggestions for some of the most prominent theoretical models<ref name="Dean2009-2" /><ref name="Elder1999" />. Among these, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM)<ref name="Pro1983">Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51(3):390-95.</ref> has received the most attention in the field due to its ease and utility in clinical practice<ref name="Dean2009-2" /><ref name="Nigg2011">Nigg CR, Geller KS, Motl RW, Horwath CC, Wertin KK, Dishman RK. A research agenda to examine the efficacy and relevance of the transtheoretical model for physical activity behaviour. Psychol Sport Exerc 2011;12(1):7-12.</ref>. It assumes that a patient’s readiness to change falls within one of five stages, based on his/her level of engagement with the particular health behaviour<ref name="Pro1983" /> | |||

Determining the patient’s stage of readiness through a series of specific questions facilitates the identification of strategies or subsequent interventions that will be most effective in guiding the patient to progress to the next stage <ref name="Elder1999" /><ref name="Nigg2011" />. The Health Behavior Change Research (HBCR) workgroup at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa provide a series of relevant questionnaires for applying the TTM to physical activity. The American Council on Exercise® (ACE) offers practical guidance on how to use the TTM to help a patient make healthy behaviour changes. Links to both the HBCR and ACE are provided below. In particular, [[Motivational Interviewing|motivational interviewing]], has gained wide acceptance as an effective means of motivating behaviour change within the TTM framework<ref name="Shin2001">Shinitzky HE, Kub J. The art of motivating behavior change: the use of motivational interviewing to promote health. Public Health Nurs 2001;18(3):178-85.</ref>. | |||

=== Methods to Promote Behaviour Change === | === Methods to Promote Behaviour Change === | ||

Behavioural counselling encompasses a spectrum of interventions, which can be rooted in one or more behavioural theories<ref name="Steptoe2001" />. Two approaches - Brief Advice and Brief Intervention - do not require extensive training to be effectively executed<ref name="CSPBrief">Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Brief Interventions: Evidence Briefing. Available at: http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/brief-interventions-evidence-briefing (Accessed 24 Nov 2013).</ref> | |||

==== Brief Advice ==== | |||

Brief Advice consists of a short (~3 minute), structured conversation with the patient aimed at raising awareness of the benefits of physical activity, exploring barriers and identifying some solutions. It may be suitable for a patient in the early stages of readiness, namely precontemplation and contemplation<ref name="Elder1999" />, or for a patient in the maintenance stage, requiring only reinforcement to maintain the behaviour<ref name="Steptoe2001" />. | |||

==== Brief Intervention ==== | ==== Brief Intervention ==== | ||

Brief Interventions are longer (~3-20 minutes), structured conversations, which delve deeper into the patient’s needs, preferences and circumstances with the aim of motivating and supporting the patient toward the behaviour change in a non-judgmental and positive manner. More time is spent discussing the benefits of the behaviour change, addressing barriers, setting goals and building confidence. | |||

=== Motivational Interviewing === | |||

[[Motivational Interviewing|Motivational interviewing]] is a behaviour change intervention that has been most recently defined as “…a collaborative, person-centred form of guiding to elicit and strengthen motivation for change”<ref name="Miller2009">Miller WR and Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cog Psych 2009;37(2):129-40.</ref>. See link. | |||

== Physical Activity 'On Prescription' == | |||

Having assessed the patient’s physical activity levels and having begun to develop a behavioural approach and partnership with the patient, the final major component of physical activity promotion at the level of the individual is the actual substance of the intervention – the health education, physical activity prescription and other ‘stuff’ received by the patient to be able to adopt and/or maintain a more physically active and less sedentary lifestyle<ref name="KhanBMJ2011" />. Interestingly, while it is generally acknowledged that physiotherapists have a significant role in health promotion and prescription<ref name="WCPT2011" />, physiotherapists’ perceptions of this role varies<ref name="ODon2012">O’Donaghue G, Cusack T, Doody C. Contemporary undergraduate physiotherapy education in terms of physical activity and exercise prescription: practice tutors’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs. Physio 2012;98(2):167-73.</ref><ref name="Shirley2010">Shirley D, van der Ploeg, HP, Bauman AE. Physical activity promotion in the physical therapy setting: perspectives from practitioners and students. Phys Ther 2010; 90:1311-22.</ref>. The next few subsections provide relevant information intended to facilitate physiotherapists in achieving this role. | |||

== | |||

=== Education === | === Education === | ||

<br> Patient education has become an essential part of health care for the patient, enabling him/her to participate in the decision-making<ref name="Hoving2010">Hoving C, Visser A, Mullen PD, van den Borne B. A history of patient education by health professionals in Europe and North America: from authority to shared decision making education. Patient Educ Couns 2010 Mar;78(3):275-81.</ref>. Critically, it is also the responsibility of physiotherapists to educate their patients. Given their unique patient contact and broad patient access (Figure 9), they are advantageously positioned to do so – in every patient, across the lifespan and among all settings<ref name="Dean2009-1" />. Furthermore, education as a physiotherapy intervention has proven to be successful for the management of low back pain<ref name="Engers2008">Engers A, Jellema P, Wensing M, van der Windt DA, Grol R, van Tulder MW. Individual patient education for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD004057.</ref> and other conditions, with a recent report of patient waiting times being cut by half as a result of a [http://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/news/press-releases/2012/october/patient-education-pilot-cuts-physiotherapy-waiting-times-in-half.aspx patient education pilot].<br> | |||

<br>Thus, by combining effective education, which should be tailored in content and delivery to the patient’s individual learning needs<ref name="Dean2009-1" />, and the principles of behavioural change, physiotherapists have the potential to achieve:<br> | |||

*Increased knowledge and awareness of risks of physical inactivity and the benefits of physical activity.<br> | |||

*Increased knowledge and awareness of physical activity, what it can entail and how it can be achieved, including use of the services available, hence increasing self-efficacy and potentiating adherence to a new lifestyle. | |||

*A change in attitudes and motivations for engaging in physical activity. | |||

*A change in beliefs and perceptions about physical activity, sedentary behaviour and social norms. | |||

==== Physical Activity ==== | |||

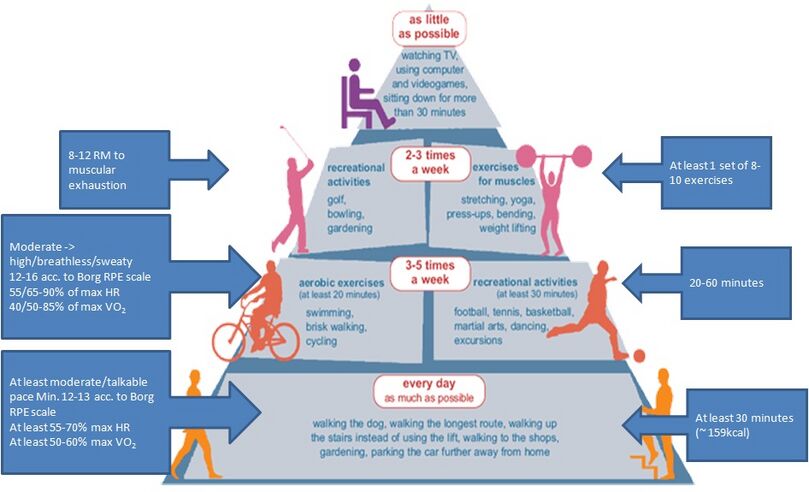

See [[Physical Activity]] link for more information including guidelines [[Image:NewPAPyramid.jpg|thumb|Figure 13. Physical Activity Pyramid |alt=|center|809x809px]] | |||

[[ | == Physical Activity and Exercise Prescription == | ||

See [[Physical Activity and Exercise Prescription]] for information. See also [[Barriers to Physical Activity]] | |||

== Summary == | |||

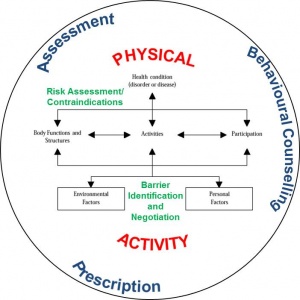

[[Image:ICFCircMod.jpg|thumb|right|Figure 16. Illustration of the process of the physical activity prescription in the context of the ICF.]]While this section on physical activity promotion at the level of the individual has been presented in a linear or sequential fashion, the phases are intertwined and continuous (Figure 16). The assessment of physical activity and stage of readiness and the provision of the prescription occur using a relevant behavioural counselling approach in the context of the patient’s biopsychosocial status, as guided by the International Classification of Function and Disability (ICF)<ref name="Rimmer2005">Rimmer JH. Use of the ICF in identifying factors that impact participation in physical activity/rehabilitation among people with disabilities. Disability and Rehab 2005;28(17):1087-95.</ref>. | |||

In a | In forming a partnership with the patient, the physiotherapist aims to understand the barriers preventing the patient from engaging in a more physically active lifestyle and begin to consider ways in which the patient may negotiate them. These barriers are not only the practical ones, such as time and equipment, but also physical and mental. In particular, identification of the patient’s physical and mental barriers, including disease or disorder, and proper, ongoing risk assessment (e.g. [http://www.csep.ca/CMFiles/publications/parq/par-q.pdf PAR-Q]) in the process of physical activity promotion is essential and the essence of why physiotherapists are ideal candidates for this role<ref name="WCPT2011" />. While risk assessment is essential it falls outside the scope of the current topic but with regards to promoting physical activity in the the following groups: | ||

<br>• Individuals who are healthy but sedentary.<br>• Individuals that are apparently health and sedentary.<br>• Individuals with comorbidities.<br>• Individuals with a disability. | |||

The same fundemental rigour of safe and competent practice remains unchanged from the policies set out by the CSP and HCPC. | |||

Ultimately, three key issues will challenge the physiotherapist and the patient: | |||

<br>1. Uptake of adequate levels of physical activity<br>2. Adherence to adequate levels of physical activity and avoidance of relapse<br>3. Avoidance of prolonged periods of physical inactivity | |||

Finally, it is important that clinicians avoid the assumption that: | |||

<br>• “If you recommend exercise, they will do it…”<br>• “If you write a programme, they will follow it…”<ref name="Handcock2003" /><br> | |||

<br> | |||

Support, guidance and follow-up are critical to the maintenance of the patient’s physical activity behaviour. Guides and leaflets, such as those produced by the CSP (below), are options of support that may be provided.<br> <br> | |||

[ | <gallery mode="packed-hover"> | ||

Image:CSPLogo.jpg|Easy Exercise Guide (link)[http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/easy-exercise-guide] | |||

Image:CSPLogo.jpg|Do you sit at a desk all day? Information Leaflets (link)[http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/do-you-sit-desk-all-day] | |||

</gallery> | |||

< | == Physical Activity Beyond The Individual == | ||

The emergence of physical activity at the heart of the public health agenda has unveiled unforeseen opportunities and unprecedented roles for physiotherapists<ref name="Eaton2012">Eaton, L. Public health presents physios with an unprecedented opportunity [Views and opinions]. 2012. Available at: http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/views-opinions (Accessed 7 November 2013).</ref>. | |||

See [[Physical Activity Promotion in the Community]] | |||

=== Volunteering === | |||

In general, [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Volunteering%3F_Keep_this_in_sight%E2%80%A6the_future_is_bright volunteering is an ever-emerging role for physiotherapists]. It can entail anything from volunteering locally to travelling abroad. | |||

= | Home:Physiotherapists can volunteer in their local communities in various ways from programme administration to teaching classes in the promotion of physical activity. <br> Abroad: With rising prevalence in physical inactivity and the rising need of NCD prevention and control in underdeveloped nations, the need for targeted physical activity promotion is being realised<ref name="GAPA2013">Global Advocacy for Physical Activity (GAPA). Global Advocacy for Physical Activity: Advocacy Council of ISPAH. 2013. Available at: http://www.globalpa.org.uk/ (Accessed 5 December 2013).</ref>, and the value of volunteering for initiatives such as GAPA cannot be dismissed. In addition, it has been estimated by the United Nations Development Programme that over 80% of the world’s 650 million disabled people reside in impoverished countries with little access to rehabilitation facilities, education, and employment. Overseas organisations are constantly looking for physiotherapists for the promotion of health and the development of rehabilitation services both in hospitals and in community-based clinics<ref name="VSO">VSO. Physiotherapists: Volunteer opportunities overseas for physiotherapists. Available at: http://www.vso.org.uk/volunteer/opportunities/community-and-social-development-health/physiotherapists (Accessed 23 November 2013).</ref>. | ||

= | == Conclusion == | ||

The Resource was created as a guide for physiotherapists and others interested in the physical activity agenda. Collating information from various sources in various media formats, it provides an overview of the relevant underpinning evidence supporting physical activity as a public health priority and the means by which it may be addressed. In particular, it focuses on the significance of the role of the physiotherapist in the promotion of physical activity at the level of the individual, in the community and in government and policy. Within each section, it offers relevant guidance and useful tools. It also offers suggestions for relevant further reading and CPD opportunities to encourage further exploration and consolidation of learning. In conclusion, given the significance of the role of the physiotherapist in the physical activity agenda, one issue remains and calls for further reflection. | |||

== References == | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Current_and_Emerging_Roles_in_Physiotherapy_Practice]] | |||

[[Category:Physical_Activity]] | |||

[[Category:Physical Activity Content Development Project]] | |||

[[Category:Queen_Margaret_University_Project]] | [[Category:Queen_Margaret_University_Project]] | ||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

Latest revision as of 03:39, 15 October 2022

Original Editors - Jason Chang, Andrea Christoforou, Maria Cuddihy, Christine Gorsek, Annika Höbler as part of the Queen Margaret University's Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Jason Chang, Andrea Christoforou, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Annika Hobler, Maria Cuddihy, Michelle Lee, Rucha Gadgil, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Evan Thomas, Christine Gorsek, Justin Louie, George Prudden and Wendy WalkerIntroduction[edit | edit source]

Physical inactivity has been deemed "the biggest public health problem of the 21st century"[1] and has been shown to kill more people than smoking, diabetes and obesity combined (Figure 1)[2]. It is ranked as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, killing approximately 3.2 million people (~6% of the total deaths) annually and accounting for approximately 32.1 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs; ~2.1% of global DALYs) annually[3].

See Physical Inactivity Link

The YouTube video by Dr. Mike Evans below provides a stimulating and compelling overview of the evidence, with some key points highlighted in the box to the right:

|

23 and 1/2 Hours:

|

Key Points: |

Sedentary Behaviour[edit | edit source]

As emphasised in the video 23 and ½ Hours and embraced by the latest physical activity guidelines, the ‘dose’ of physical activity that seems to confer the majority of these health benefits (in adults) is 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity on most days of the week[5]. However, one aspect of physical activity promotion that this dose recommendation does not address is sedentary behaviour. See Sedentary behaviour link.

Given the amount of time potentially spent sitting each day evidence suggests that short breaks in sedentary time can confer substantial health benefits [6][7], as highlighted in the short video below.

|

Is Sitting On Your Backside Dangerous?[8]

|

Thus, it is clear that the physical activity paradigm should incorporate sedentary behaviour[9], and physical activity initiatives and recommendations should adapt accordingly [10][11].

The Development and Evolution of Physical Activity Guidelines[edit | edit source]

Beginning with Morris’ work on occupational physical activity in the 1950s [12], the evidence emerging from the years of epidemiological research of the risks associated with inactivity or a sedentary lifestyle provided the rationale for the development of physical activity guidelines[5]. Identifying the appropriate ‘dose’ of physical activity that would extract the greatest reward in public health requires an ongoing examination of data emerging from both epidemiological and exercise training studies. It also requires the decision to focus these recommendations on the population who would benefit most, namely those who are inactive, thus contributing to the public health burden[13][5].

See Physical Activity link for guidelines and more.

Physiotherapists have the potential to make a substantial impact on individual, community and public health. Their holistic, biopsychosocial[14], and non-invasive approach, professional autonomy[15], specialist knowledge and skill set[16], relatively prolonged patient contact time and varied clinical practice populations and settings (including prisons) places the physiotherapist in the ideal position for the widespread promotion of physical activity (Figure 9)[17][18][19].

In the past, physiotherapy intervention, including exercise prescription, has predominantly focused on the restoration of function lost as a result of an acute incident or on the maintenance of function in neurological or cardio-respiratory disease[20]. However, a shift in the public health agenda towards the prevention or management of chronic lifestyle conditions, including NCDs, obesity, osteoarthritis and depression[21], and towards the mitigation of the effects of ageing in an increasingly ageing population[22] has demanded a change in the role of the physiotherapist in addressing this need through the widespread promotion of physical activity (and other health-promoting lifestyle changes)[18]. Recognising this emerging role and “professional and ethical responsibility”[18], physiotherapy professional bodies around the world have brought physical activity promotion to the forefront of their agenda with links to two clear examples - CSP and WCPT - provided below.

Physical Activity For The Individual[edit | edit source]

Physical activity promotion at the level of the individual is not a novel concept. As first points of contact, primary care providers, particularly GPs, have acknowledged a necessary role in physical activity promotion for decades, with varying degrees of follow-through in different countries[23]. The various medical-practitioner-based physical activity schemes developed have typically involved (1) links to commercial exercise centres; (2) the provision of simple advice on physical activity or (3) a behavioural counselling approach to the provision of physical activity advice[24].

Assessing Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Assessment is an important tool in the physiotherapist's arsenal, enabling the collection of relevant information for a clinically-reasoned, holistic and patient-centred approach to diagnosis and subsequent management. Despite the evidence, patients’ habitual physical activity and sedentary levels are generally not assessed as part of the standard physiotherapy assessment[25].Yet, all patients coming into contact with a physiotherapist suffer from and/or are susceptible to the effects of physical inactivity, regardless of their presenting complaint. Thus, the assessment of physical activity and sedentary levels has a relevant place in the physiotherapy examination[26].

In the general medicine community, physical activity has been declared the fifth vital sign[27] – a modifiable sign that should be assessed at every clinical encounter[27][28]. Different approaches may be used to measure levels of physical activity (e.g. observation, heart rate monitors, motion sensors), but questionnaires are likely to be the most appropriate in the context of a typical physiotherapy assessment, given time and resource constraints[26]. Three alternatives for the assessment of a patient’s physical activity levels are described below.

The Kaiser Permanente Approach: The ‘Exercise Vital Sign’[edit | edit source]

Kaiser Permanente is a not-for-profit, California-based integrated managed care consortium that have adopted a simple method for assessing physical activity levels in each patient, at every visit[29]. Coined the ‘Exercise Vital Sign' (EVS), it is a brief screening tool that consists of two questions and has shown good face and discriminant validity[30]. It is described in the 40-second video below.

|

Kaiser Permanente: Making Exercise a Vital Sign[31]

|

Key Points: The EVS: "2 questions, 1 minute" [27] 1) “On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate or greater physical activity?” 2) “On those days, how many minutes do you engage in activity at this level?” |

Mobilising Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is a complex, multifactorial (Figure 3) and multi-dimensional (Figure 7) health behaviour[32][33]. The role of the physiotherapist in counselling a patient to adopt, change or maintain such a behaviour can be equally complex. It may involve forming a partnership with the patient[34], defining the target behaviour (e.g. increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary behaviour), exploring and addressing the unique combination of personal, socio-cultural, environmental, policy factors underlying the patient’s behaviour[32] [35] and identifying the most suitable (patient-centred) approach(es) to mobilise and help the patient sustain the behaviour[36]. Long-term adherence to physical activity is essential for the health benefits to be realised[37].

Several theoretical models of and counselling approaches for health behaviour change have been developed[38][39]. A working knowledge of these models and the various approaches to their practical application is another essential tool in the physiotherapist’s arsenal, if s/he is to help effect and sustain behaviour change in the patient.

A summary of these models and approaches is provided below.

Theoretical Models of Health Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Table 2 provides a brief description of and practical suggestions for some of the most prominent theoretical models[38][39]. Among these, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM)[40] has received the most attention in the field due to its ease and utility in clinical practice[38][41]. It assumes that a patient’s readiness to change falls within one of five stages, based on his/her level of engagement with the particular health behaviour[40]

Determining the patient’s stage of readiness through a series of specific questions facilitates the identification of strategies or subsequent interventions that will be most effective in guiding the patient to progress to the next stage [39][41]. The Health Behavior Change Research (HBCR) workgroup at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa provide a series of relevant questionnaires for applying the TTM to physical activity. The American Council on Exercise® (ACE) offers practical guidance on how to use the TTM to help a patient make healthy behaviour changes. Links to both the HBCR and ACE are provided below. In particular, motivational interviewing, has gained wide acceptance as an effective means of motivating behaviour change within the TTM framework[42].

Methods to Promote Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Behavioural counselling encompasses a spectrum of interventions, which can be rooted in one or more behavioural theories[36]. Two approaches - Brief Advice and Brief Intervention - do not require extensive training to be effectively executed[43]

Brief Advice [edit | edit source]

Brief Advice consists of a short (~3 minute), structured conversation with the patient aimed at raising awareness of the benefits of physical activity, exploring barriers and identifying some solutions. It may be suitable for a patient in the early stages of readiness, namely precontemplation and contemplation[39], or for a patient in the maintenance stage, requiring only reinforcement to maintain the behaviour[36].

Brief Intervention[edit | edit source]

Brief Interventions are longer (~3-20 minutes), structured conversations, which delve deeper into the patient’s needs, preferences and circumstances with the aim of motivating and supporting the patient toward the behaviour change in a non-judgmental and positive manner. More time is spent discussing the benefits of the behaviour change, addressing barriers, setting goals and building confidence.

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Motivational interviewing is a behaviour change intervention that has been most recently defined as “…a collaborative, person-centred form of guiding to elicit and strengthen motivation for change”[44]. See link.

Physical Activity 'On Prescription'[edit | edit source]

Having assessed the patient’s physical activity levels and having begun to develop a behavioural approach and partnership with the patient, the final major component of physical activity promotion at the level of the individual is the actual substance of the intervention – the health education, physical activity prescription and other ‘stuff’ received by the patient to be able to adopt and/or maintain a more physically active and less sedentary lifestyle[28]. Interestingly, while it is generally acknowledged that physiotherapists have a significant role in health promotion and prescription[16], physiotherapists’ perceptions of this role varies[45][46]. The next few subsections provide relevant information intended to facilitate physiotherapists in achieving this role.

Education[edit | edit source]

Patient education has become an essential part of health care for the patient, enabling him/her to participate in the decision-making[47]. Critically, it is also the responsibility of physiotherapists to educate their patients. Given their unique patient contact and broad patient access (Figure 9), they are advantageously positioned to do so – in every patient, across the lifespan and among all settings[18]. Furthermore, education as a physiotherapy intervention has proven to be successful for the management of low back pain[48] and other conditions, with a recent report of patient waiting times being cut by half as a result of a patient education pilot.

Thus, by combining effective education, which should be tailored in content and delivery to the patient’s individual learning needs[18], and the principles of behavioural change, physiotherapists have the potential to achieve:

- Increased knowledge and awareness of risks of physical inactivity and the benefits of physical activity.

- Increased knowledge and awareness of physical activity, what it can entail and how it can be achieved, including use of the services available, hence increasing self-efficacy and potentiating adherence to a new lifestyle.

- A change in attitudes and motivations for engaging in physical activity.

- A change in beliefs and perceptions about physical activity, sedentary behaviour and social norms.

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

See Physical Activity link for more information including guidelines

Physical Activity and Exercise Prescription[edit | edit source]

See Physical Activity and Exercise Prescription for information. See also Barriers to Physical Activity

Summary[edit | edit source]

While this section on physical activity promotion at the level of the individual has been presented in a linear or sequential fashion, the phases are intertwined and continuous (Figure 16). The assessment of physical activity and stage of readiness and the provision of the prescription occur using a relevant behavioural counselling approach in the context of the patient’s biopsychosocial status, as guided by the International Classification of Function and Disability (ICF)[49].

In forming a partnership with the patient, the physiotherapist aims to understand the barriers preventing the patient from engaging in a more physically active lifestyle and begin to consider ways in which the patient may negotiate them. These barriers are not only the practical ones, such as time and equipment, but also physical and mental. In particular, identification of the patient’s physical and mental barriers, including disease or disorder, and proper, ongoing risk assessment (e.g. PAR-Q) in the process of physical activity promotion is essential and the essence of why physiotherapists are ideal candidates for this role[16]. While risk assessment is essential it falls outside the scope of the current topic but with regards to promoting physical activity in the the following groups:

• Individuals who are healthy but sedentary.

• Individuals that are apparently health and sedentary.

• Individuals with comorbidities.

• Individuals with a disability.

The same fundemental rigour of safe and competent practice remains unchanged from the policies set out by the CSP and HCPC.

Ultimately, three key issues will challenge the physiotherapist and the patient:

1. Uptake of adequate levels of physical activity

2. Adherence to adequate levels of physical activity and avoidance of relapse

3. Avoidance of prolonged periods of physical inactivity

Finally, it is important that clinicians avoid the assumption that:

• “If you recommend exercise, they will do it…”

• “If you write a programme, they will follow it…”[24]

Support, guidance and follow-up are critical to the maintenance of the patient’s physical activity behaviour. Guides and leaflets, such as those produced by the CSP (below), are options of support that may be provided.

Physical Activity Beyond The Individual[edit | edit source]

The emergence of physical activity at the heart of the public health agenda has unveiled unforeseen opportunities and unprecedented roles for physiotherapists[50].

See Physical Activity Promotion in the Community

Volunteering [edit | edit source]

In general, volunteering is an ever-emerging role for physiotherapists. It can entail anything from volunteering locally to travelling abroad.

Home:Physiotherapists can volunteer in their local communities in various ways from programme administration to teaching classes in the promotion of physical activity.

Abroad: With rising prevalence in physical inactivity and the rising need of NCD prevention and control in underdeveloped nations, the need for targeted physical activity promotion is being realised[51], and the value of volunteering for initiatives such as GAPA cannot be dismissed. In addition, it has been estimated by the United Nations Development Programme that over 80% of the world’s 650 million disabled people reside in impoverished countries with little access to rehabilitation facilities, education, and employment. Overseas organisations are constantly looking for physiotherapists for the promotion of health and the development of rehabilitation services both in hospitals and in community-based clinics[52].

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

The Resource was created as a guide for physiotherapists and others interested in the physical activity agenda. Collating information from various sources in various media formats, it provides an overview of the relevant underpinning evidence supporting physical activity as a public health priority and the means by which it may be addressed. In particular, it focuses on the significance of the role of the physiotherapist in the promotion of physical activity at the level of the individual, in the community and in government and policy. Within each section, it offers relevant guidance and useful tools. It also offers suggestions for relevant further reading and CPD opportunities to encourage further exploration and consolidation of learning. In conclusion, given the significance of the role of the physiotherapist in the physical activity agenda, one issue remains and calls for further reflection.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century [warm up].J Sports Med 2009;43(1):1-2.

- ↑ Khan KM, Tunaiji HA. As different as Venus and Mars: time to distinguish efficacy (can it work?) from effectiveness (does it work?) [warm up]. Br J Sports Med 2011;45(10):759-760.

- ↑ Global Health Observatory (GHO). Prevalence of physical inactivity 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/index.html (Accessed 20 November 2013).

- ↑ DocMikeEvans. 23 and 1/2 hours: What is the single best thing we can do for our health?. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUaInS6HIGo (Accessed 18 November 2013).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Blair SN, LaMonte MJ, Nichaman MZ. The evolution of physical activity recommendation: how much is enough? Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79(5):913S-920S.

- ↑ Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Cerin E, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Owen N. Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk. Diabetes Care 2008;31(4):661-6.

- ↑ Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, Winkler EAH, Owen N. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003-06. Eur Heart J 2011;32(5):590-7.

- ↑ Risk Bites. Is sitting on your backside dangerous?. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COIGHiMveG4 (Accessed 26 November 2013).

- ↑ Katzmarzyk PT. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and health: paradigm paralysis or paradigm shift? Diabetes 2010;59:2717-2725.

- ↑ Hamilton MT, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Zderic TW, Owen N. Too little exericse and too much sitting: inactivity physiology and the need for new recommendations on sedentary behavior. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports 2008;2(4):292-8.

- ↑ Yates T, Wilmot EG, Khunti K, Biddle S, Gorely T, Davies MJ. Stand up for your health: is it time to rethink the physical activity paradigm? Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2011;93(2):292-4.

- ↑ Paffenbarger RS Jr, Blair SN, Lee IM. A history of physical activity, cardiovascular health and longevity: the scientific contributions of Jeremy N Morris, DSc, DPH, FRCP. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30(5):1184-92.

- ↑ Lee IM, Skerrett PJ. Physical activity and all-cause mortality: what is the dose-response relation? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33(6):S459-71.

- ↑ Sanders T, Foster NE, Bishop A, Ong BN. Biopsychosocial care and the physiotherapy encounter: physiotherapists’ accounts of back pain consultations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:65

- ↑ Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC). Physiotherapists: standards of proficiency. 2013. Available at: http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10000DBCStandards_of_Proficiency_Physiotherapists.pdf. (Accessed 3 December 2013).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 World Confederation for Physical Therapy. Policy statement: physical therapists as exercise experts across the life span. 2011. Available at: http://www.wcpt.org/policy/ps-exercise%20experts (Accessed 28 November 2013).

- ↑ Khan K. Guest editorial: physiotherapists as physical activity champions. Physiotherapy Practice 2013 Available at: http://sunshinephysio.com/resources/articles/PhysicalActivityChampions.pdf (Accessed 28 November 2013).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Dean E. Physical therapy in the 21st century (Part I): Toward practice informed by epidemiology and the crisis of lifestyle conditions. Physiother Theory Prac 2009;25(5-6):330-353.

- ↑ Europa. Presentation of ER-WCPT commitment in the EU platform on diet, physical activity and health. 2012. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/ev20121114_co04_en.pdf (Accessed 28 November 2013).

- ↑ Verhagen E, Engbers L. The physical therapist’s role in physical activity promotion. Br J Sports Med 2009;43(2):99-101

- ↑ Global Health Observatory (GHO). Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/en/index.html Accessed 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Spijker J, MacInnes J. Population ageing: the timebomb that isn’t? Brit Med J 2013;347:f6598.

- ↑ Weiler R, Stamatakis E. Physical activity in the UK: a unique crossroad? Brit J Sports Med 2010;44:912-4

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Handcock P, Jenkins C. The Green Prescription: a field of dreams? J New Zealand Med Assoc, 2003;116(1187):1-5.

- ↑ Petty N.J. Neuromusculoskeletal Examination and Assessment: A Handbook for Therapists. 2001. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hussey J, Wilson F. Measurement of Activity Levels is an important part of physiotherapy assessment. Physiotherapy 2003;89(10):585-93.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Sallis R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:473-74

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Khan KM, Weiler R, Blair SN. Prescribing exercise in primary care. BMJ 2011;343

- ↑ Sallis, R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:473-4

- ↑ Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, Quinn VP, Koebnick C, Young DR, Sternfeld B, Sallis RE. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44(11):2071-6

- ↑ AHIPResearch. Kaiser Permanente: Making Exercise a Vital Sign. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hxfp0LOaLMM Accessed 02 December 2013.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not?. Lancet 2012;380(9838):258-71.

- ↑ Pettee Gabriel KK, Morrow JR Jr, Woolsey AL. Framework for physical activity as a complex and multidimensional behaviour. J Phys Act Health 2012;9(Suppl 1):S11-8.

- ↑ Jonas S, Phillips EM. ACSM’s Exercise is MedicineTM: A Clinician’s Guide to Exercise Prescription. American College of Sports Medicine 2009 Philadelphia.

- ↑ Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J. Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther 1993;73(11):771-82.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Steptoe A, Kerry S, Rink E, Hilton S. The impact of behavioural counselling on stage of change in fat intake, physical activity, and cigarette smoking in adults at increased risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Public Health 2001;91(2):265-9.

- ↑ Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-Term Adherence to Health Behavior Change. Am J Lifestyle Medicine 2013:1-10.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Dean E. Physical therapy in the 21st century (Part II): Evidence-based practice within the context of evidence-informed practice. Physiother Theory Prac 2009;25(5-6):354-68.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Elder JP, Ayala GX, Harris S. Theories and intervention approaches to health-behaviour change in primary care. Am J Prev Med 1999;17(4):275-84.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51(3):390-95.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Nigg CR, Geller KS, Motl RW, Horwath CC, Wertin KK, Dishman RK. A research agenda to examine the efficacy and relevance of the transtheoretical model for physical activity behaviour. Psychol Sport Exerc 2011;12(1):7-12.

- ↑ Shinitzky HE, Kub J. The art of motivating behavior change: the use of motivational interviewing to promote health. Public Health Nurs 2001;18(3):178-85.

- ↑ Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Brief Interventions: Evidence Briefing. Available at: http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/brief-interventions-evidence-briefing (Accessed 24 Nov 2013).

- ↑ Miller WR and Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cog Psych 2009;37(2):129-40.

- ↑ O’Donaghue G, Cusack T, Doody C. Contemporary undergraduate physiotherapy education in terms of physical activity and exercise prescription: practice tutors’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs. Physio 2012;98(2):167-73.

- ↑ Shirley D, van der Ploeg, HP, Bauman AE. Physical activity promotion in the physical therapy setting: perspectives from practitioners and students. Phys Ther 2010; 90:1311-22.

- ↑ Hoving C, Visser A, Mullen PD, van den Borne B. A history of patient education by health professionals in Europe and North America: from authority to shared decision making education. Patient Educ Couns 2010 Mar;78(3):275-81.

- ↑ Engers A, Jellema P, Wensing M, van der Windt DA, Grol R, van Tulder MW. Individual patient education for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD004057.

- ↑ Rimmer JH. Use of the ICF in identifying factors that impact participation in physical activity/rehabilitation among people with disabilities. Disability and Rehab 2005;28(17):1087-95.

- ↑ Eaton, L. Public health presents physios with an unprecedented opportunity [Views and opinions]. 2012. Available at: http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/views-opinions (Accessed 7 November 2013).

- ↑ Global Advocacy for Physical Activity (GAPA). Global Advocacy for Physical Activity: Advocacy Council of ISPAH. 2013. Available at: http://www.globalpa.org.uk/ (Accessed 5 December 2013).

- ↑ VSO. Physiotherapists: Volunteer opportunities overseas for physiotherapists. Available at: http://www.vso.org.uk/volunteer/opportunities/community-and-social-development-health/physiotherapists (Accessed 23 November 2013).

![Easy Exercise Guide (link)[1]](/images/7/76/CSPLogo.jpg)