Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome

Original Editor - User:Andrew Klaehn, Yelena Gesthuizen as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Admin, Yelena Gesthuizen, Laure VanderDonckt, Andrew Klaehn, Michelle Lee, Adam Vallely Farrell, Lucinda hampton, Wanda van Niekerk, Kim Jackson, Charlotte Moreau, Rucha Gadgil, Jess Bell, Candace Goh, Claire Knott, 127.0.0.1, Naomi O'Reilly and Gitte Verdoodt

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome (SLJ) is a juvenile osteochondrosis and traction epiphysitis affecting the extensor mechanism of the knee which disturbs the patella tendon attachment to the inferior pole of the patella. The tenderness of the inferior pole of the patella is usually accompanied by roentgenographic evidence of splintering of that pole. Most patients with SLJ also show a calcification at the inferior pole of the patella.[1]

Sinding Larsen Johansson syndrome is an inflammation of the bone at the bottom of the patella (kneecap), where the tendon from the shin bone (tibia) attaches. It is an overuse knee injury rather than a traumatic injury.

The syndrome usually appears in adolescence, during the growth spurt. It’s associated with localised pain which is worsened by exercise. Usually we observe a localised tenderness and soft tissue swelling. There is also a tightness of the surrounding muscles, the quadriceps, hamstrings and gastrocnemius in particular. This tightness usually results in inflexibilities of the knee joint, altering the stress through the patellofemoral joint.[2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The Sinding-Larsen Johansson Syndrome is a rupture or avulsion of the patellar ligament at the distal point of the patella caused by traction[4]. The patellar ligament or tendon is the distal part of the tendon of the M. Rectus Femoris, part of the quadriceps femoris, which is a continuation of it. It goes over the patella and is attached to the tibial tuberosity. It’s other attachment is the spina iliaca anterior inferior. The most superficial fibers originate from the rectus femoris, the deepest layer from the vastus intermedius and the intermediate layer from the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis.[5]

The distal pole of the patella is shown on the picture.

The syndrome may lead to tendinitis, which is an inflammation of the tendon, and calcification in the ligament. This means that calcium deposits in the substance of the tendon. The presence of such can cause an increase in rupture rate, slower recovery times and a higher frequency of complications after surgery.[6]

For a more detailed review of the Knee Anatomy.

Epidemiology/ Etiology[edit | edit source]

In 1991 and 1992 Sinding-Larsen and Johansson respectively and independently described a syndrome, in the adolescent consisting of tenderness at the inferior pole of the patella accompanied by radiographic evidence of fragmentation of the pole. This is the Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease (SLJD), and has been used as an umbrella term for the syndrome that causes pain of the inferior pole of the patella accompanied by fragmentation of the pole or a calcification at the pole.[7]

SLJ is mostly caused by repeated microtrauma. The syndrome typically affects children and adolescents between the ages of ten and fifteen years old and athletes. However, it can also affect active adults who run for moderate to long distances or are involved in sports that require much jumping or squatting. In adolescents, repeated traction on the distal pole of the patella from quadriceps muscle contractions creates this synchondrosis at the tip of the patella. This can be followed by calcification and ossification if the condition becomes chronic. The pain is caused by the abnormal motion of the synchondrosis area that appears mainly after an acute injury event or repeated microtrauma.[8] The diagnosis of SLJ can be difficult to make, it is used as a general term for all pain conditions at the pole of the patella but its etiology is not clear.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Ultrasound (US) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) may show osseus fragmentation of the distal patellar pole, or it may be irregular, with chondral changes and thickening at the insertion of the patellar tendon. Any activity, from normal walking to climbing stairs, may increase the person's pain depending upon the severity of the condition. In less severe cases, a person may not begin to feel pain until after extended activity, such as running for several miles. The pain occurs when straightening the knee against force: deep knee bends, kneeling, jumping, climbing stairs, squatting, running, weightlifting.[9] Tenderness to touch, limping and a tender bump in the infrapatellar area are all common signs. Lower extremity neurovascular signs or crepitus in the knee are rare and may be indicative of another pathology.

During a subjective assessment a patient will often report the following; Localised pain, swelling or tenderness felt at the front of the knee - base of your patella

Patients are typically young active boys aged 10 to 13 years. Symptoms are usually;

- Worse with exercise, stair climbing, squatting, kneeling, jumping and running.

- May report that they limp after exercise.

- May be unilateral or bilateral.

- Is relieved by rest

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome is a self-limiting syndrome. Complete recovery can be expected with closure of the patella growth plate. Although symptoms of Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome may linger for months, few patients have poor outcomes with conservative treatment, and surgical intervention is generally not necessary. Corticosteroid injections are not recommended due to case reports of subcutaneous atrophy.[10]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Other diseases with similar symptoms to the Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome are injury to the infrapatellar fat pad, Hoffa disease, patellofemoral joint dysfunction, mucoid degeneration of the infrapatellar tendon.[11]

The clinical presentation of the Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome(SLJD) can be difficult to differ from other injuries or diseases like a sleeve fracture, osteochondritis, stress fracture of the patella, tendinopathy of the patella tendon[7] and Osgood-Schlatter's disease.[12]

The difference between a sleeve fracture, osteochondritis and a stress fracture is difficult based on the radiographic findings. The SLJD results from overuse while the sleeve fracture is due to a trauma (acute) with an explosive acceleration that causes rapid contraction of the quadriceps while the knee is flexed. This mechanism causes an avulsion of the periosteum, retinaculum, and cartilage of the patella.[13] So with the anamnesis (patient's account of the mechanism) the distinction can easily be made. Likewise osteochondritis is related to overuse just like the SLJD. On the other hand, a stress fracture is a partial or complete fracture of the bone due to lower force repeated stress. The etiology between these three injuries (SLJD, osteochondritis and a stress fracture) does not differ sufficiently. Following this further investigation need to be performed. Tendinopathy (jumper’s knee) and SLJD can appear at the same time. Further studies have to clarify the differences between SLJD and osteochondritis, stress fracture and tendinopathy. For this purpose magnetic resonance images and pathological examinations can be performed.[7]

Research shows that the Osgood-Schlatter disease and SLJD incidence is 4 times greater in sport-specialised athletes than in multisport athletes. Osgood-Schlatter disease and Sinding Larsen Johansson syndrome may in some cases appear in the same patient at the same time.[7][14]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The physiotherapist performs a physical examination of the knee and reviews the patient’s symptoms. In case of anterior knee pain there are three important tests to perform. In all tests the patient is in supine position.

Patellar Grind Test[15];Tester places thumb web-space just above the patella, then asks to contract their quad forcefully. The test is positive if there is pain or grinding.

Compression Test[16][17]; Hard downward pressure is applied with rotation, pain indicates meniscal injury.

Extension Resistance Test[18]

SLJ can be a difficult diagnosis to make. To confirm SLJ ,arthroscopic excision of the distal pole of the patella is an effective procedure to check the tendon and return to sports within a few months. An ultrasound has proven to be a reliable method for the diagnosis of knee joint osteochondrosis .

Medlar[1] identified four radiographic stages of the disease process:

- stage 1, normal findings

- stage 2, irregular calcifications at the inferior pole of the patella

- stage 3, coalescence of the calcification

- stage 4A, incorporation of the calcification into the patella to yield a normal radiographic configuration of the area

- stage 4B, a coalesced calcification mass separated from the patella.

Clinically, however, radiographic abnormalities at the inferior patella seem to vary; there are several pathogenesis reported; apophysitis, periostitis, tendinopathy, calcification accompanied by avascular necrosis, or osteochondritis.[7]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The Kujala anterior knee pain scale and the Lower extremity functional scale can be used for both an initial screening tool as well as to detect changes with treatment and as outcome measures.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome has a similar radiographic appearance with injuries as a sleeve fracture, osteochondritis of the patella, stress fracture of the patella and tendinopathy of the patellar tendon. In particular, sleeve fractures, osteochondritis and stress fractures are scarcely distinguished based on the radiographic pictures. So further evaluation with MR imaging is necessary to differentiate these injuries. This further evaluation is also needed because the exact degree of damage is often underestimated; the lateral radiographs may reveal an unusually elevated position of the patella (with regard to the femur and one or multiple small bony fragments nearby to the inferior pole of the patella).[7][19]

As mentioned before, this syndrome is caused by traction on the patellar tendon and this causes inflammation. SLJS can be distinguished from patellar tendinopathy by the presence of bone marrow oedema in the patella. MR image illustrates thickening and increased signal of the proximal patellar tendon and irregular ossification of the inferior pole of the patella with underlying bone marrow oedema.[19]

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome is often confused with the Osgood–Schlatter disease as also has been mentioned before.

Physical Therapy Treatment[edit | edit source]

Referral to an MD for anti-inflammatories should be initiated. First and foremost, physical therapists must educate the patient on activity modification. Kneeling, jumping, squatting, stair climbing, and running on the affected knee should be avoided at least for the short term. Lower extremity strength needs to be tested, especially at the ankle and the hip to find any muscle weaknesses that may be contributing to the overuse syndrome. Core strengthening should be initiated as well as exercise addressing flexibility or strength issues. The goal in patients with SLJ is to avoid muscle atrophy. This can also be achieved by electrotherapy.[11]

The conservative therapy should consist of eccentric exercises, isokinetic strengthening and viscosupplementation. This was used for only one patient in a case report, so the level of evidence is not very high.[9]

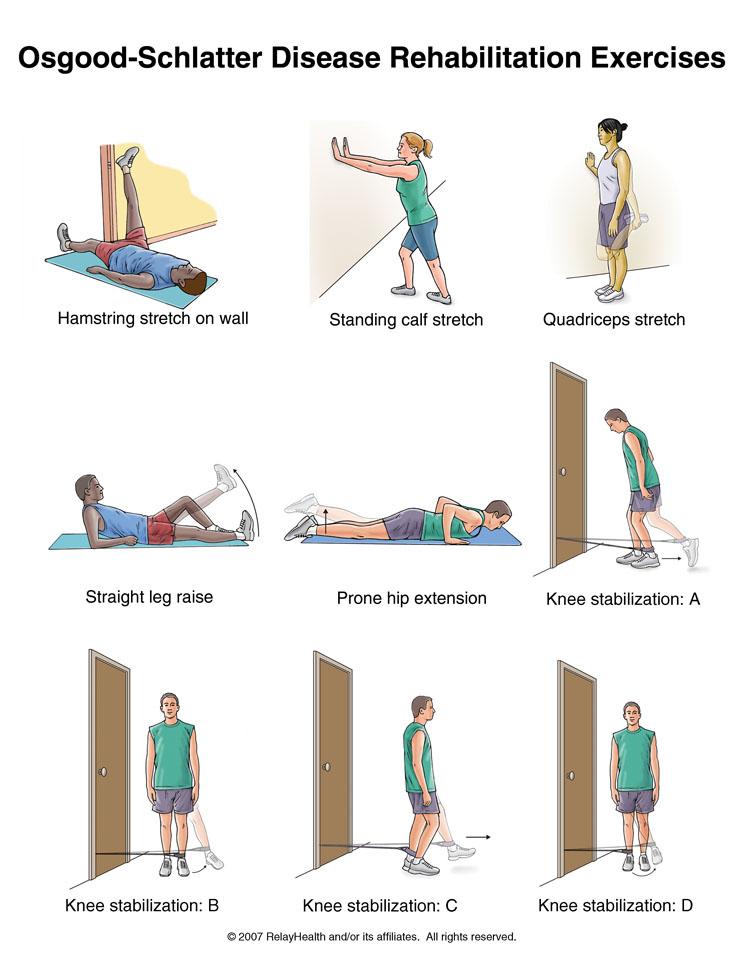

This picture, with several exercises you can do for the SLJ Syndrome, comes from the site of a physiotherapy practice in Belgium, it’s an expert’s opinion and so it is not fully researched.[20]

If the patient doesn’t respond (the pain doesn’t decrease), it can be possible to give platelet-rich plasma injections. These are given in the synchondrosis area under ultrasound guidance.[9]

Stretching and proprioceptive muscle strengthening exercises in patients with anterior knee pain, have been proven beneficial.[21] An improvement of strength and functionality can be accomplished by both open and closed kinetic chain exercises.[22]

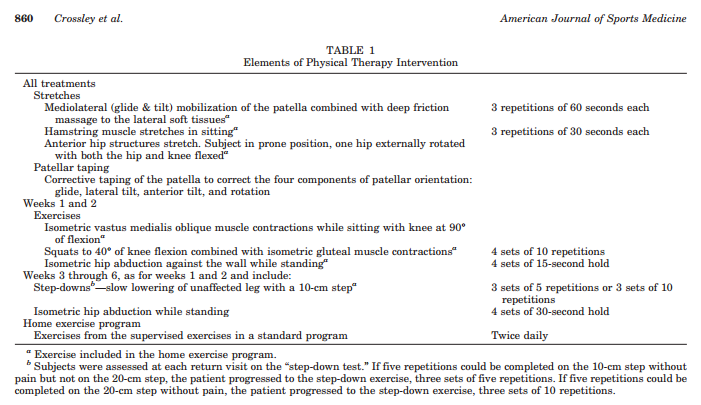

Patients who followed a 30 to 60 minute physical therapy intervention, once a week during six weeks showed a decrease in patellofemoral pain. Table one shows the content of the therapy.[23]

An adjunct treatment that has been proven beneficial for tendinopathy or tenosynovitis problems is the ASTYM system.[24]

A safe progression back to sports or high-level activities may happen when each of the following happens in this specific order:

- The lower kneecap is no longer tender and there is no swelling.

- The injured knee can be fully straightened and bent without pain.

- The knee and leg have regained normal strength compared to the uninjured knee and leg

- Ability to jog straight ahead without limping.

- Ability to sprint straight ahead without limping.

- Ability to do 45-degree cuts.

- Ability to do 90-degree cuts.

- Ability to do 20-yard figure-of-eight runs.

- Ability to do 10-yard figure-of-eight runs.

- Ability to jump on both legs without pain and hop on the injured leg without pain.[23]

If there has been no progress, then an operation may be necessary. After the operation full weight bearing is allowed with two canes without an immobilisation splint for the first week. Then therapy can start after one week, with knee exercises to regain joint range of motion. The first six weeks will consist of eccentric quadriceps exercises and jumping and other more functional movements are allowed after three months. This strategy was, again, used for only one specific patient and is not fully researched.[9]

Medical Treatment[edit | edit source]

Before medical treatment can be considered, conservative treatment has to be performed starting with limiting sports activities and anti-inflammatory medications, physical therapy and local corticosteroid injections.[25] These injections are used because they reduce the pain very efficiently and rapidly. However they are not recommended if alternatives relieve the symptoms sufficiently. This is because they cause significant damage to the tendon when repeated or with an insufficient injection interval.[12] If the conservative treatment is not effective, more specifically when there is a continued decrease in activity levels for more than 3 months, then surgery is the preferred treatment strategy.[25]

Surgical treatment allows patients to return to their prior activity level with a complete pain relief. There are many surgical options and each one of them show great results.[25]

Arthroscopic excision is one of the options. Arthroscopic excision of the the distal pole of the patella ensures the tendon to be checked. The rehabilitation starts about 1 week after the surgery. Patients can return to sports activities within a few months.[9]

On the other hand there are some studies that claim that long term complications appear. These complications could be osteoarthritis and patellofemoral arthritis. Further research with long term follow-up is needed to determine whether those complications do appear and if other complications arise.[25]

There are very few studies who describe Sinding Larsen Johansson medical treatment (surgery).However in this retrieved evidence the success of this treatment is evident.[9][25]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

The knee is a very complex joint with a lot of tendinous, ligamentous and meniscal attachments which leaves it particularly vulnerable to complex injuries after a trauma. The concern remains on the radiologist to both identify the pattern of injury and maintain an understanding of the frequent substantial underlying damage it signifies. By recognizing the significance of these injuries at the time of initial presentation, radiologists can ease proper patient work-up in the hope of preventing the chronic rate associated with delayed treatment.[21]

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is one of the most common disorders between adolescent athletes and is multifactorial in nature. The Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome usually appears in children after a period of rapid growth.[23]

Sport specialiSation in female adolescents is associated with increased risk when compared to multi-sport athletes. Both multi-sport and sport specialiSed athletes may participate in strict training programs. However, those female adolescents dedicated to one sport seems to have a higher risk. In addition, apophyseal injuries of Osgood-Schlatter Disease and Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Syndrome were four times greater in sport-specialiSed athletes compared to multi-sport athletes.[12]

What we can conclude is that early sport specialisation is associated with increased risk of anterior knee pain disorders including Sinding Larsen-Johansson syndrome (also PFP and Osgood Schlatter).

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Medlar, R. C., et al., ‘Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disease. Its Etiology and Natural History’, Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, December 1978, vol. 60, no. 8, p. 1113-1116. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ Houghton, K. M., ‘Review for the generalist: evaluation of anterior knee pain’, Paediatric Rheumatology, (2007), vol. 5, p. 4-10. (Level of Evidence 2B)

- ↑ Medlar, R. C., et al., ‘Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disease. Its Etiology and Natural History’, Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, December 1978, vol. 60, no. 8, p. 1113-1116. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ Louis Solomon, ‘Apley’s System of Orthopaedics and Fractures’, 9th. edition, (2010), p. 575-576, (https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B9QqiQN8RwSnQk1CVjFsNUQyUEk/view) (Level of Evidence 5)

- ↑ Karl Grob, ‘New insight in the architecture of the quadriceps tendon’, J Exp Orthop., 2016; 3: 32, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5095096/) (Level of Evidence 2b)

- ↑ Francesco Olivia, ‘Physiopathology of intratendinous calcific deposition’, BMC Medicine, 2012 (http://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1741-7015-10-95) (Level of Evidence 3a)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Iwamoto, Jun, et al. "Radiographic abnormalities of the inferior pole of the patella in juvenile athletes." The Keio journal of medicine 58.1 (2009): 50-53. (Level of Evidence 3b)

- ↑ Kajetanek, C., et al. "Arthroscopic treatment of painful Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome in a professional handball player." Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 102.5 (2016): 677-680. (Level of Evidence 4)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Demetrious, T. and B., Harrop (red.), Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disease, internet, 2008, (http://www.physioadvisor.com.au/10246650/sindinglarsenjohansson-disease-physioadvisor.htm). (Level of Evidence 5)

- ↑ http://physioworks.com.au/injuries-conditions-1/sinding-larsen-johansson-disease

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Klucinec, B., ‘Recalcitrant Infrapatellar Tendinitis and Surgical Outcome in a Collegiate Basketball Player: A Case Report’, Journal of Athletic Training, June 2001, vol. 36, no. 2, p. 174-181. (Level of Evidence 1C)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Hall, Randon1, Barber Foss, Kim2, Hewett, Timothy E.3, Myer, Gregory D.2, “Sport Specialization’s Association With an Increased Risk of Developing Anterior Knee Pain in Adolescent Female Athletes.”, Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 2015, Vol. 24 Issue 1, p. 31-35 (Level of Evidence 2b)

- ↑ Derek S. Damrow, BS; Scott E. Van Valin, MD, ‘Patellar Sleeve Fracture With Ossification of the Patellar Tendon’, MONTH/MONTH 201x | Volume xx • Number X, p.1-3. LoE 5

- ↑ Hall, Randon1, Barber Foss, Kim2, Hewett, Timothy E.3, Myer, Gregory D.2, “Sport Specialization’s Association With an Increased Risk of Developing Anterior Knee Pain in Adolescent Female Athletes.”, Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 2015, Vol. 24 Issue 1, p. 31-35 (Level of Evidence 2b)

- ↑ http://slideplayer.com/slide/4311148/, Hip, Thigh, and Knee. ILIUM Acetabulum Ischium Ischial Tuberosity Pubis. (Photo)

- ↑ http://www.slideshare.net/JLS10/kin191-ach6kneepatellofemoralevaluation (Photo)

- ↑ http://www.fpnotebook.com/ortho/exam/AplysCmprsnTst.htm (Photo)

- ↑ https://meded.ucsd.edu/clinicalmed/neuro2.htm (Photo)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Christopher J. Gottsegen, MD, Benjamin A. Eyer, MD, Eric A. White, MD, Thomas J. Learch, MD, and Deborah Forrester, MD, “Avulsion Factures of the Knee: Imaging Findings and Clinical Significance”, Musculoskeletal and Vascular Emergencies in the Extremities, 2008, Vol. 28, Issue 6 (Level of Evidence 2b)

- ↑ http://www.orthopedielier.be/2-patint/95-sinding-larsen-johansson/ (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Clark, D.I., et al., ‘Physiotherapy for Anterior Knee Pain. A Randomised Controlled Trial’, Ann Rheum Dis, 2000, 59, p. 700-704. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ Witvrouw, E., et al., ‘Open Versus Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises for Patellofemoral Pain. A Prospective Randomised Study’, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2000, vol. 28, no. 5, p. 687-694. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Crossley, K., et al., ‘Physical Therapy for Patellofemoral Pain. A Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial’, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2002, vol. 30, no. 6, p. 856-865. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ Wilson, J.K., et al., 'Comparison of rehabilitation methods in the treatment of patellar tendinitis', Journal of Sports Rehabilitation, 2000, 9(4), p. 304-314. (Level of Evidence 1B)

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 GeorGe T. MaTic, BS; DaviD c. FlaniGan, MD, “Efficacy of Surgical Interventions for a Bipartite Patella”, CME article ORTHOPEDICS, september 2014 | Volume 37 • Number 9, p. 623-628(Level of Evidence 2a)