Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) for Low Back Pain

Pain Neuroscience Education[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

PNE[edit | edit source]

LBP[edit | edit source]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Clinician perspective[edit | edit source]

A clinician’s perspective to a treatment would concern assessing the relevant outcome measure to determine the effectiveness from that treatment / intervention. In the context of PNE and LBP, the consensus amongst research is that pain, and disability are dominant outcome measures used and can be applied through different questionnaires to evaluate these outcomes. Other outcome measures used in research include psychosocial elements to them such as quality of life, self-efficacy, Catastrophizing and kinesiophobia.

Outcome measures to evaluate PNE & LBP[edit | edit source]

QOL - EQ-5D

Kinesiophobia – Tampa scale

Catastrophizing - pain catastrophizing scale

PNE[edit | edit source]

Systematic review evidence that investigated the effect PNE has on musculoskeletal and low back pain in patients included studies that evaluated the effect of PNE as a stand alone intervention. 2 studies from Woods and Hendrick (2018) and 5 studies from Louw et al (2016) contained information regarding PNE's individual effect. Results showed that no study was able significantly decrease pain and there was low to moderate evidence for improving disability in the short term or at all in regards to given outcome measures in the reviews[1][2].

Whilst PNE's effectiveness on physical attributes are not as applicable as a stand-alone intervention, PNE's stand-alone effect on psychosocial components shows promising evidence to support its use. Evidence suggests that PNE can improve other elements that can facilitate function such as kinesiophobia and illness perceptions [3]. However, limited evidence, although favourable, can't solely justify the individual application of PNE therefore future research needs to investigate this further.

PNE and Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Clinicians will often incorporate the application of PNE in alignment with usual physiotherapy care (manual therapy/exercise prescription) as to utilise a multi-modal approach when treating chronic back pain [4]

There is compelling evidence to support that PNE along with physiotherapy interventions having short term improvements on pain and disability [1][2][5]. Information regarding the mentioned evidence does not specify what type of physiotherapy intervention is superior to one another.

However, emerging research has found propitious evidence to support PNE alongside motor control training (MCT) as its suggested to deliver more effective results in improving pain and disability compared to current best-evidence physiotherapy care [6][7] . MES has also shown better results compared to core stability exercise [8], although this result was exclusive to women due to the population studied thus limiting its ecological validity.

With limited evidence it is hard to distinguish which intervention format is more effective to combine with PNE and therefore warrants the need for further research to determine clear differences in the interventions. Updating current systematic evidence could help establish clearer findings.

PNE and physiotherapy effect on psychological aspects of patients showed potential improvements to kinesiophobia and catstrophization but improvements were negligible failing to demonstrated clinically meaningful changes[1] .

Type of physiotherapy care used with PNE[edit | edit source]

- Manual therapy

- Exercise prescription

- Aquatic therapy

- Paced/Graded exposure

- Acupuncture/dry needling

- Motor control training

Patient perspective[edit | edit source]

A patient’s treatment perspective involves two main components: the patient’s views about their health (e.g. what the condition is, what its causes are and how serious it is to the patient) and the patient’s values (e.g. what will help them most and how this can be achieved).

Patients values and beliefs[edit | edit source]

Minimal research investigates the patient’s values in learning about their pain. However, a mixed-methods survey found that patients believed PNE was necessary for their improvement of persistent pain. PNE as an intervention provides a coherent biological explanation for how emotions such as stress can initiate a hormonal response which can sensitise neural processes associated with pain[2]. Pain reconceptualisation helps manage stress and anxiety, limiting the pain induced by these emotions. Although there’s limited research in this area, a mixed-methods review provides contextualised insight into qualitative data on the research question providing a foundation for refining PNE to focus on pain concepts deemed most valuable to people with pain and use patient-centred language to best communicate the concepts.

A common belief that follows pain is the concept that pain means damage; therefore, learning that pain does not indicate bodily or tissue damage can help manage patients’ pain. These findings are consistent with the fear-avoidance model, which describes how individuals may develop musculoskeletal pain due to avoidant behaviour based on fear[9]. When a patient is gradually exposed to fear situations, understanding fear-avoidance concept leads to less fear of injury and less avoidance of movement and behaviours. If a patient engages, pain may become less threatening, changing their priority from pain control to valued life goals, e.g., decreasing disability and kinesiophobia, through using positive connotations such as "understanding that even though it hurts, it is not a sign of damage"[2][10].

Future research[edit | edit source]

There are still areas within PNE that need to be further researched. One shortcoming is the heterogeneity of studies as age range, gender, and education don’t tend to be considered. Bilterys et al. (2022)[11] found no clinically meaningful differences in the effectiveness of PNE between educational levels. However, this has minimal research and would be beneficial to further understand patient factors affecting PNE.

Clinical application of PNE[edit | edit source]

There is limited evidence which evaluates the most effective use of pain neuroscience education. Within the current literature, session delivery varies from 1:1 sessions to group sessions, with some sessions lasting as little as 10-20 minutes while others lasted greater than one hour. One aspect of PNE with little controversy is that PNE produces the most favourable outcomes when used in conjunction with more 'traditional' physiotherapy treatments.

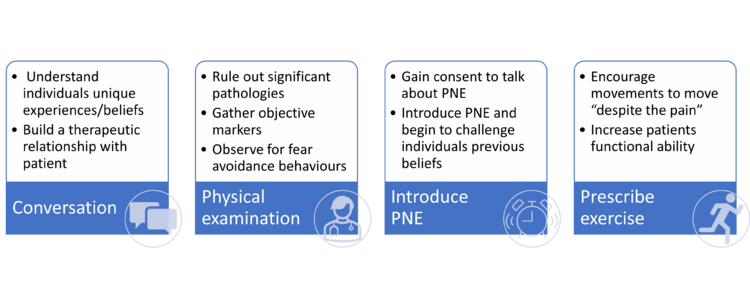

Utilising the current literature, in particular a study from Louw et al. (2016), we have outlined a strategy which clinicians can utilise to incorporate PNE into their practice.

First session[edit | edit source]

Within the first session, a comprehensive assessment of the patient will be completed. This is like a 'traditional physiotherapy assessment' as it gathers both subjective and objective information which the clinician can utilise to inform their diagnosis and treatment. We propose the first session should be split into 4 sections which should total to around 1 hour:

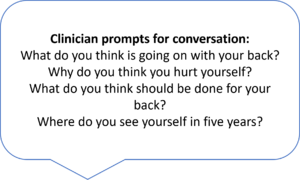

- Conversation/interview: Initially clinicians should have a conversation with the patient where they predominantly listen to the patient, gathering information about their experiences, suffering and beliefs. This part should not be rushed, and adequate time is needed for the patient to tell their own story. Within this time the clinician can take note of any issues/beliefs which the patient mentions which may need to be addressed in later PNE sessions.

- Physical examination: It is important that significant pathologies are ruled out to ensure that there is no underlying sinister pathology. Physical examination will also give us objective markers that we can utilise to track the progress of individuals to see if treatment is effective. The results from this examination should be conveyed to the patient, with emphasis on the use of clinician language to avoid terms like “wear and tear” which have negative connotations.

- Introduction to PNE: Depending on the time availability of the clinician following a thorough assessment, PNE can then be briefly introduced to the patient. A good way to start the conversation is asking “Has anyone explained to you why you are still experiencing pain?”. If the patient is interested in learning more this is when a brief metaphor can be used to start to explain the hyper sensitive nervous system which is contributing to their pain.

- Exercise prescription: As PNE is most effective when used in conjunction with other therapies, simple exercises should be given to the patient to encourage movement. The patient should perform the exercise during the session and the clinician should discuss the patients perception of the exercise, challenging any inaccurate beliefs utilising the PNE metaphor.

'Homework'[edit | edit source]

It is important that we encourage patients to take an active role in their own recovery. We should provide patients with the relevant tools to enable this and increase their self-efficacy. Giving patients a few simple tasks can help to promotes this. These can include:

- Question Generation: Encourage the patient to write down any questions that they may have regarding pain and the PNE material covered in the session. This helps to remove doubts and increase their understanding of pain experiences.

- Encourage exercises: Exercise help to enhance movement and increase function. A focus on breathing and relaxation should be emphasised during the exercise with reference to PNE and relaxation of the hypersensitive nervous system.

- Aerobic exercise: Starting very small in an exercise of their own choice (walking, swimming, cycling, running etc.) patients should be encouraged to participate in aerobic exercise. The benefits should be explained to the patient in terms of the down regulation of the sensitised nervous system.

- Set goals: Patient should be encouraged to list 5 goals they wish to achieve prior to the next session. Asking the patient “If you could flip a switch and get rid of all your pain, what would you do again?”

Clinicians should use their own judgement when giving patient tasks to complete at home, some proactive patients will complete all tasks before the next session, while those with low self efficacy may be overwhelmed when given a large number of tasks. One way to combat this is to give patient 1-2 tasks at a time, a clinician should use their own judgement to determine the tasks to prescribe and what tasks can be introduced in later sessions.

Subsequent sessions[edit | edit source]

Subsequent session should be individualised to patients and their journey with PNE. The content of these sessions are dependent on what was covered in the previous session e.g. if there was not time in the last session to discuss the importance of aerobic exercise or to teach the patients relaxed breathing techniques then this could be a priority for the next session. A useful structure for later PNE could be:

- Question and answer: Discuss any questions the patient had about the previous session. If patients do not have any questions the clinician could ask the patient about what they understood from the previous session, this can help identify any areas which patients were unsure of or had forgotten which can then be revisited.

- Progress PNE: New metaphors, pictures or information can be discussed with the patient. These should be relevant to the patients experience or findings.

- Review goals: Break the patients goals down into SMART goals. This encourages pacing and graded exposure which can help to motivate patients throughout their journey. Each session the goals should be reviewed, and patient should be encouraged to progress to the next stage if appropriate.

- Traditional therapy: The clinician should use their own clinical judgement to determine if the patient would benefit from other treatments such as manual therapy. The exercises from previous session should be reviewed and new exercises prescribed to encourage increase function.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wood, L. and Hendrick, P.A. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of pain neuroscience education for chronic low back pain: Short-and long-term outcomes of pain and disability. European Journal of Pain, 23(2), pp.234–249. doi:10.1002/ejp.1314.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Louw, A., Zimney, K., Puentedura, E.J. and Diener, I. (2016). The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 32(5), pp.332–355. doi:10.1080/09593985.2016.1194646.

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":2" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Malfliet, A., Kregel, J., Meeus, M., Roussel, N., Danneels, L., Cagnie, B., Dolphens, M. and Nijs, J. (2017). Blended-Learning Pain Neuroscience Education for People With Chronic Spinal Pain: Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial. Physical Therapy, 98(5), pp.357–368. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzx092.

- ↑ Saracoglu, I., Arik, M.I., Afsar, E. and Gokpinar, H.H. (2020). The effectiveness of pain neuroscience education combined with manual therapy and home exercise for chronic low back pain: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, pp.1–11. doi:10.1080/09593985.2020.1809046.

- ↑ Puentedura, E.J. and Flynn, T. (2016). Combining manual therapy with pain neuroscience education in the treatment of chronic low back pain: A narrative review of the literature. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 32(5), pp.408–414. doi:10.1080/09593985.2016.1194663.

- ↑ Malfliet, A., Kregel, J., Coppieters, I., De Pauw, R., Meeus, M., Roussel, N., Cagnie, B., Danneels, L. and Nijs, J. (2018). Effect of Pain Neuroscience Education Combined With Cognition-Targeted Motor Control Training on Chronic Spinal Pain. JAMA Neurology, 75(7), p.808. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0492.

- ↑ Rabiei, P., Sheikhi, B. and Letafatkar, A. (2020). Comparing pain neuroscience education followed by motor control exercises with group‐based exercises for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Practice. doi:10.1111/papr.12963.

- ↑ Gorji, S.M., Mohammadi Nia Samakosh, H., Watt, P., Henrique Marchetti, P. and Oliveira, R. (2022). Pain Neuroscience Education and Motor Control Exercises versus Core Stability Exercises on Pain, Disability, and Balance in Women with Chronic Low Back Pain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), p.2694. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052694.

- ↑ Cosio D. (2019) Fear-Avoidance and Chronic Pain: Helping Patients Stuck in the Mouse Trap. Practical Pain Management, 19(5), Available at:https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/treatments/psychological/cognitive-behavioral-therapy/fear-avoidance-chronic-pain-helping-patients

- ↑ Louw, A., Diener, I., Butler, D.S. and Puentedura, E.J., (2011). The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 92(12), pp.2041-2056.

- ↑ Bilterys, T., Kregel, J., Nijs, J., Meeus, M., Danneels, L., Cagnie, B., Van Looveren, E. and Malfliet, A., (2022). Influence of education level on the effectiveness of pain neuroscience education: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 57, p.102494.