Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) for Low Back Pain: Difference between revisions

Luke Dunmore (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

== '''Introduction''' == | == '''Introduction''' == | ||

== '''PNE''' == | |||

=='''LBP'''== | |||

== '''Evidence''' == | == '''Evidence''' == | ||

| Line 60: | Line 58: | ||

=== Patient perspective === | === Patient perspective === | ||

== Clinical application of PNE == | |||

There is limited evidence which evaluates the most effective use of pain neuroscience education. Within the current literature, session delivery varies from 1:1 sessions to group sessions, with some sessions lasting as little as 10-20 minutes while others lasted greater than one hour. One aspect of PNE with little controversy is that PNE produces the most favourable outcomes when used in conjunction with more 'traditional' physiotherapy treatments. | |||

Utilising the current literature, in particular a study from Louw et al. (2016), we have outlined a strategy which clinicians can utilise to incorporate PNE into their practice. | |||

=== First session === | |||

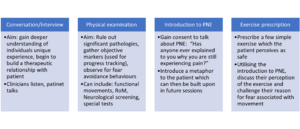

Within the first session, a comprehensive assessment of the patient will be completed. This is like a 'traditional physiotherapy assessment' as it gathers both subjective and objective information which the clinician can utilise to inform their diagnosis and treatment. We propose the first session should be split into 4 sections which should total to around 1 hour: | |||

[[File:Introducing PNE into clinical practice.png|center|thumb]] | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 16:59, 20 May 2022

Pain Neuroscience Education[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

PNE[edit | edit source]

LBP[edit | edit source]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Clinician perspective[edit | edit source]

A clinician’s perspective to a treatment would concern assessing the relevant outcome measure to determine the effectiveness from that treatment / intervention. In the context of PNE and LBP, the consensus amongst research is that pain, and disability are dominant outcome measures used and can be applied through different questionnaires to evaluate these outcomes. Other outcome measures used in research include psychosocial elements to them such as quality of life, self-efficacy and kinesiophobia.

Outcome measure to evaluate PNE & LBP[edit | edit source]

QOL - EQ-5D

Kinesiophobia – Tampa scale

PNE[edit | edit source]

systematic review evidence has found that PNE as a stand-alone intervention has low evidence supporting its effectiveness for pain relief and low-moderate evidence for improving disability in the short term or at all in regards to given outcome measures in the reviews[1][2].

Whilst PNE's effectiveness on physical attributes are not as applicable as a stand-alone intervention, PNE's stand-alone effect on psychosocial components shows promising evidence to support its use. Evidence suggests that PNE can improve other elements that can facilitate function such as kinesiophobia and illness perceptions [3]. However, limited evidence, although favourable, can't solely justify the individual application of PNE therefore future research needs to investigate this further.

PNE and Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Clinicians will often incorporate the application of PNE in alignment with usual physiotherapy care (manual therapy/exercise prescription) as to utilise a multi-modal approach when treating chronic back pain [4]

There is moderate evidence to support that PNE along with physiotherapy interventions can have short term improvements on pain and disability [1][5]. Long term effects of PNE on pain and disability in low back pain is unclear due to a lack of evidence to support strong conclusions.

Emerging research has found propitious evidence to support PNE alongside motor control training (MCT) as its suggested to deliver more effective results in improving pain and disability compared to current best-evidence physiotherapy care (education and general back exercise) [6][7] . MES has also shown better results compared to core stability exercise [8], although this result was exclusive to women due to the population studied thus limiting its ecological validity.

With limited evidence it is hard to distinguish which training format is superior to one another and therefore warrants the need for further research to determine clear differences in the interventions. Updating current systematic evidence could help establish clearer findings.

Other interventions[edit | edit source]

acupuncture

dry needling

Patient perspective[edit | edit source]

Clinical application of PNE[edit | edit source]

There is limited evidence which evaluates the most effective use of pain neuroscience education. Within the current literature, session delivery varies from 1:1 sessions to group sessions, with some sessions lasting as little as 10-20 minutes while others lasted greater than one hour. One aspect of PNE with little controversy is that PNE produces the most favourable outcomes when used in conjunction with more 'traditional' physiotherapy treatments.

Utilising the current literature, in particular a study from Louw et al. (2016), we have outlined a strategy which clinicians can utilise to incorporate PNE into their practice.

First session[edit | edit source]

Within the first session, a comprehensive assessment of the patient will be completed. This is like a 'traditional physiotherapy assessment' as it gathers both subjective and objective information which the clinician can utilise to inform their diagnosis and treatment. We propose the first session should be split into 4 sections which should total to around 1 hour:

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wood, L. and Hendrick, P.A. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of pain neuroscience education for chronic low back pain: Short-and long-term outcomes of pain and disability. European Journal of Pain, 23(2), pp.234–249. doi:10.1002/ejp.1314.

- ↑ Louw, A., Zimney, K., Puentedura, E.J. and Diener, I. (2016). The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 32(5), pp.332–355. doi:10.1080/09593985.2016.1194646.

- ↑ Malfliet, A., Kregel, J., Meeus, M., Roussel, N., Danneels, L., Cagnie, B., Dolphens, M. and Nijs, J. (2017). Blended-Learning Pain Neuroscience Education for People With Chronic Spinal Pain: Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial. Physical Therapy, 98(5), pp.357–368. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzx092.

- ↑ Saracoglu, I., Arik, M.I., Afsar, E. and Gokpinar, H.H. (2020). The effectiveness of pain neuroscience education combined with manual therapy and home exercise for chronic low back pain: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, pp.1–11. doi:10.1080/09593985.2020.1809046.

- ↑ Puentedura, E.J. and Flynn, T. (2016). Combining manual therapy with pain neuroscience education in the treatment of chronic low back pain: A narrative review of the literature. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 32(5), pp.408–414. doi:10.1080/09593985.2016.1194663.

- ↑ Malfliet, A., Kregel, J., Coppieters, I., De Pauw, R., Meeus, M., Roussel, N., Cagnie, B., Danneels, L. and Nijs, J. (2018). Effect of Pain Neuroscience Education Combined With Cognition-Targeted Motor Control Training on Chronic Spinal Pain. JAMA Neurology, 75(7), p.808. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0492.

- ↑ Rabiei, P., Sheikhi, B. and Letafatkar, A. (2020). Comparing pain neuroscience education followed by motor control exercises with group‐based exercises for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Practice. doi:10.1111/papr.12963.

- ↑ Gorji, S.M., Mohammadi Nia Samakosh, H., Watt, P., Henrique Marchetti, P. and Oliveira, R. (2022). Pain Neuroscience Education and Motor Control Exercises versus Core Stability Exercises on Pain, Disability, and Balance in Women with Chronic Low Back Pain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), p.2694. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052694.