Lumbar Differential Diagnosis

Top Contributors - Jess Bell, Carin Hunter, Jorge Rodríguez Palomino and Ewa Jaraczewska

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Low back pain is a common presenting condition in physiotherapy clinics. The physiotherapy assessment aims to screen for serious spinal conditions and identify impairments that may have contributed to the onset of the pain, or which increase the likelihood of an individual developing persistent pain. These include biological factors (eg. weakness, stiffness), psychological factors (eg. depression, fear of movement and catastrophisation) and social factors (eg. work environment).[1]

Once serious spinal pathology and specific causes of back pain have been ruled out, an individual is classified as having non-specific low back pain. If no serious pathology is suspected, there is no indication for x-rays or MRI diagnostic imaging unless the results of imaging may change / guide the management protocol.[2][3]

90% of patients presenting to primary care with low back pain are classified as having non-specific low back pain.[4][5] Non-specific low back pain is defined as "low back pain not attributable to a recognizable, known specific pathology[6] (eg, infection, tumor, osteoporosis, lumbar spine fracture, structural deformity, inflammatory disorder, radicular syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome)"[7] Non-specific does not mean that there is no tissue causing nociception, just that it is not as clear and not as concerning.[8]

Non-specific low back pain is usually categorised into three subtypes: acute, sub-acute and chronic low back pain.[9] This subdivision is based on how long the individual has had low back pain. Acute low back pain is an episode of low back pain that has been present for less than 6 weeks, sub-acute low back pain has been present for between 6 and 12 weeks and chronic low back pain has been present for 12 weeks or more.[10]

Diagnosis versus Classification[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis and classification are defined in more detail here. Typically when we discuss diagnoses, we talk about pathoanatomical diagnoses. There are also many classification systems for low back pain, some more commonly used than others. The goal of a classification system is to guide treatment, and ensure that clinicians don't treat all cases of back pain the same.[8]

Imaging[edit | edit source]

For more information on referring for imaging, please see Practical Decision Making in Physiotherapy Practice, but key points to consider are as follows:[8]

- imaging is needed if red flags are present or if there is no improvement with conservative care within 6 weeks. If you are unsure about a red flag, you can often treat the patient a little to see if they improve.

- imaging is recommended if it will change the course of treatment.[11]

- a lot of imaging findings correlate with low back pain. This doesn’t mean that everyone with imaging findings will have pain, but often the more findings there are on imaging, the higher the chance that the person will have pain. We can still help these people though!

Potential Conditions in the Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

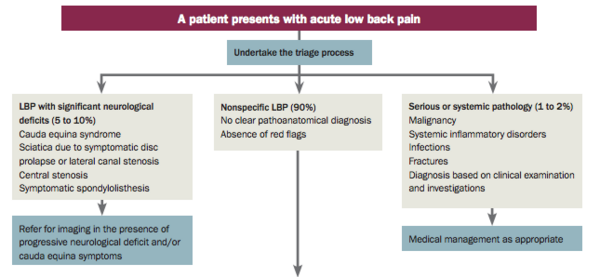

Differential diagnosis is a key part of the physiotherapy assessment process. After a comprehensive lumbar assessment, you can triage the patient, as explained in the Lumbar Assessment page (see figure below).

You will need knowledge of Red Flags and to consider a range of conditions (see linked pages for more information).

- Specific Low Back Pain

- Cauda Equina Syndrome

- Lumbar Radiculopathy

- Disc Herniation

- Spinal Stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Piriformis Syndrome

- Sacroiliac Joint Pain (not dysfunction)

- Osteoarthritis

- Sciatica

- Thoraco-Lumbar Junction Syndrome (also called Maigne syndrome)

"Have a hypothesis. The more thoughtful you are the better you’ll become." - Nick Rainey

Sources of Pain[edit | edit source]

When completing a lumbar differential diagnosis, you will need to consider if there is extremity pain or just spinal pain. Then you will need to determine if the spine is contributing to the extremity pain (i.e. spinogenic) or if the extremity is the source.

A few key factors to consider when looking at the source of pain:[8]

- if there are movement restrictions in the spine, there is a higher chance that distal symptoms are from the spine[12]

- there is a higher likelihood that the spine is the source of pain if the extremity has full range of motion[12]

- "current spinal pain" raises the pre-test probability that extremity pain has a spinal source from 10% to 19% overall[13]

- a high percentage of people who have pain in their hip, thigh or leg have spinogenic pain[13]

- paraesthesia more commonly arises from the spine than the extremities[12]

- if a change in posture affects symptoms, pain is more likely coming from the spine[12]

During an assessment, it is important to remember that while neurological testing isn't exact, it is close. "We just need to figure out where do we need to treat and what gets those distal symptoms better."[8]

Pathoanatomical Approach Compared to a Signs and Symptoms Approach[edit | edit source]

"A pathoanatomical approach means that you are treating to improve anatomy while a signs and symptoms approach means you test signs and ask for symptoms, treat, and then retest to assess for progress."[8] - Nick Rainey

After our assessment, we should consider the asterisk signs that we have made note of throughout our examination and use these to help decide how to treat using a "signs and symptoms" treatment approach.

An asterisk sign is also known as a comparable sign. It is something that you can reproduce/retest that often reflects the primary complaint. It can be functional or movement specific. It is used to measure if symptoms are improving or worsening.

Differentiating between Hip and Lumbar Pain[edit | edit source]

In this video you can see a live patient examination differentiating between hip and lumbar pain.

The following tables detail a range of conditions associated with low back pain.

| Syndrome | Findings | Assessment/Plan |

|---|---|---|

| Facet syndrome | History and physical examination:

Radiological findings (not indicated on intial evaluation):

|

Differential diagnosis:

Treatment:

|

| Sacro-iliac joint syndrome | History and physical examination:

Radiological findings (not indicated on intial evaluation): – Differential diagnosis:

|

Functional disturbance:

Treatment:

|

| Myofascial pain syndrome | History and physical examination:

Radiological and histological findings:

|

Local treatment:

|

| Functional instability | History and physical examination:

Radiological findings:

|

|

| Disease | Findings | Further Evaluation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

Fracture

|

|

Imaging studies:

Laboratory testing:

|

Conservative:

Surgical:

Prevention:

|

| Massive disc herniation |

|

|

Surgical:

|

| Bacterial infection (spondylitis/ spondylodiscitis, epidural or paravertebral abscess) |

|

|

The indication for conservative vs. operative treatment (debridement, filling of defects, instrumentation) depends on:

|

| Tumor |

|

Imaging studies: local at first, then staging studies to rule out instability (SINS):

Laboratory tests:

|

Neurologic deficit present:

Neurologic deficit absent:

Conservative:

|

| Disease | Findings | Further Evaluation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disk herniation |

|

Imaging studies: (DD herniation vs. stenosis vs. tumor)

Neurological/electrophysiological testing:

|

Depending on the clinical findings:

|

| Spinal canal stenosis /

degenerative instability |

|

Abnormally flexed posture of trunk imaging studies:

Neurological/electrophysiological testing:

|

Depending on the clinical findings:

|

| Axial spondylitis and

seronegative spondylo - arthropathy |

Inflammatory back pain syndrome

|

Imaging studies:

|

|

Deformities

|

Clinical features:

|

Early detection in children!

|

Depending on the patient’s age and on the cause and severity of the deformity:

|

| Herpes zoster |

|

Lumbar puncture and CSF examination:

|

|

| Diabetic radiculopathy |

|

|

Pharmacotherapy:

|

| Neuroborreliosis |

|

Lumbar puncture and CSF examination:

|

|

| Spinal ischemia |

|

|

|

Key to abbreviations:

- CBC: complete blood count

- CRP: C-reactive protein

- CT: computerized tomography

- EMG: electromyography

- ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

- SINS: spinal instability in neoplastic disease

- SSEP: somatosensory evoked potentials

- AB: antibodies

- CT: computerized tomography

- CSF: cerebrospinal fluid

- DD: differential diagnosis

- ENG: electroneurography

- EMG: electromyography

- MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

- NCS: nerve conduction study

- NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PDA: peridural anesthesia

- SSEP: somatosensory evoked potentials

- SSNRI: selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

- TCA: tricyclic antidepressant

Additional Resources[edit | edit source]

Podcast Links:[edit | edit source]

- The Back Pain Podcast: Piriformis syndrome

- The Back Pain Podcast: Is my pain from my sacroiliac joint?

- Modern Pain Podcast: Lumbar Stenosis

- The Back Pain Podcast Episode 82: Flexion, Extension, Radicular Pain & Disc Pathology with Adam Meakins and Dr. Mark Laslett

Journal Articles and Books:[edit | edit source]

- Casser HR, Seddigh S, Rauschmann M. Acute lumbar back pain: investigation, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2016 Apr;113(13):223.

- Casiano VE, Dydyk AM, Varacallo M. Back pain.

Physiopedia Pages:[edit | edit source]

- Low Back Pain

- Lumbar Assessment

- Low Back Pain Guidelines

- Differentiating Inflammatory and Mechanical Back Pain

- Non Specific Low Back Pain

- Specific Low Back Pain

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ M.Hancock. Approach to low back pain. RACGP, 2014, 43(3):117-118.

- ↑ Hall AM, Aubrey-Bassler K, Thorne B, Maher CG. Do not routinely offer imaging for uncomplicated low back pain. bmj. 2021 Feb 12;372.

- ↑ Almeida M, Saragiotto B, Richards B, Maher C. Primary care management of non-specific low back pain: key messages from recent clinical guidelines. Med J Aust 2018; 208 (6): 272-275

- ↑ Traeger A, Buchbinder R, Harris I, Maher C. Diagnosis and management of low-back pain in primary care. CMAJ. 2017 Nov 13;189(45):E1386-E1395.

- ↑ Koes BW, Van Tulder M, Thomas S. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Bmj. 2006 Jun 15;332(7555):1430-4.

- ↑ Otero-Ketterer E, Peñacoba-Puente C, Ferreira Pinheiro-Araujo C, Valera-Calero JA, Ortega-Santiago R. Biopsychosocial Factors for Chronicity in Individuals with Non-Specific Low Back Pain: An Umbrella Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Aug 16;19(16):10145.

- ↑ Balagué, Federico, et al. "Non-specific low back pain." The Lancet 379.9814 (2012): 482-491. Level of evidence 1A

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Rainey N. Differential Diagnosis Course. Physiopedia Plus. 2023.

- ↑ Hock M, Járomi M, Prémusz V, Szekeres ZJ, Ács P, Szilágyi B, Wang Z, Makai A. Disease-Specific Knowledge, Physical Activity, and Physical Functioning Examination among Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Sep 23;19(19):12024.

- ↑ Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ, Hollis S. Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subchronic low back trouble. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Mar 15;20(6):722-8.Level of evidence 3C

- ↑ Al-Hihi E, Gibson C, Lee J, Mount RR, Irani N, McGowan C. Improving appropriate imaging for non-specific low back pain. BMJ Open Quality. 2022 Feb 1;11(1):e001539.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Rastogi R, Rosedale R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. Exploring indicators of extremity pain of spinal source as identified by Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT): a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study. J Man Manip Ther. 2022 Jun;30(3):172-9.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rosedale R, Rastogi R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. A study exploring the prevalence of Extremity Pain of Spinal Source (EXPOSS). Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2020 Aug 7;28(4):222-30.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Casser HR, Seddigh S, Rauschmann M. Acute lumbar back pain: investigation, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2016 Apr;113(13):223.